Tijuana

Street market in Tijuana. Photo by Richard Mora.

Tijuana, the largest border city in Mexico, is a fusion of worlds. Located fifteen miles south of San Diego, California, the city draws migrants, tourists, and adventurers. Here, some of them cross paths with the locals, who proudly self-identify as Tijuanenses and embody the city’s lively, and seemingly chaotic rhythm. Allow me to give you a glimpse into Tijuana, or ‘T.J.’ as tourists refer to it, or ‘Tijuas’ as many young Tijuanenses call their home.

“Tia Juana”

Doña Otilia, a woman in her seventies, assured me this past summer that the city is named after a woman, Tía Juana, who was one of its early mestizo settlers. I had no reason to doubt her; after all it is what I had been told repeatedly as a child. It turns out, however, that this narrative is more cuento than fact. Historical documents record the name Tía Juana as early as 1809, but this name was that of a ranch, not a person. According to La Sociedad de Historia de Tijuana, the city’s name likely came from the semi-nomadic peoples that inhabited the region in pre-Hispanic times—the Tecuan, Teguan, Ticuan, Teguana, and Llantiguan.

Moreover, the official date of Tijuana’s founding adds to the intrigue of this city’s beginnings. The date was not decided upon until 1976, after numerous public hearings held in the early 1970s. Members of various professional organizations, including La Sociedad de Historia de Tijuana, la Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, and Instituto Tecnológico de Tijuana as well as individual community members were in attendance. Eventually, it was decided that the official founding date would be July 11, 1889, the date of the first recorded urban plan for the city.

The city shield of Tijuana bears the inscription: “Aquí empieza la Patria.” With these words, Tijuanenses affirm their patriotism. However, the plight of the migrants from other regions of Mexico that pour into the city every year leads them to Tijuana, not because this is where la Patria begins, but because it is where it ends with the United States in sight.

Migrant Dreams

My grandmother recalls that when she arrived to Tijuana nearly fifty years ago that the flow of migrants from points further south was not noteworthy. She says, “antes venían contaditos.” But that is no longer true. Tijuana has grown at an astronomical pace. In 1940, there were approximately 16,000 residents. By 1950, the figure had risen dramatically to 60,000. Currently, about two million people reside in Tijuana. Many come drawn by the possibility of finding work, either across the US-Mexico border, or at one of the foreign-owned maquiladoras (assembly factories) that have become fixtures of the local economy.

For some, Tijuana is a new beginning, the launching pad from which to venture into the future and escape the past. There are migrants who have decided to settle down and make a life in Tijuana over the years. Take for example Doña Otilia. She arrived in Tijuana, having traveled by bus, days after the death of Pedro Infante, the Mexican crooner, in April of 1957. Here, she and her husband raised a family in a small house they bought after years of saving. Yet, even now, Doña Otilia speaks nostalgically of someday retracing her migrant path to “mi rancho,” as she often refers to her pueblo in the state of Michoacan. However, in all actuality, she will stay in Tijuana, where she buried her husband and a son within the past year.

For others, Tijuana is as close as they are able to come to the U.S. They find themselves surrounded by a border city that reminds them of their frustrated aspirations. Dreams dissipate and nightmares materialize for many migrants seeking to cross the border. Standing at the corners of some main intersections throughout Tijuana, many different souls vie for motorists’ attention and money. Every day, one hears radio announcements from families desperately searching for loved ones—sons and daughters, who made their way to Tijuana and have not been heard from since. Likewise, listeners are informed when migrant families seek to sell their furniture because they are heading back home, some with money and others without.

“Tantas colonias que uno ni conoce”

The most noticeable change that has resulted from the population growth is the dramatic increase in the number of homes. Fifty years ago, city officials were giving out parcels of hillside land to newcomers in an effort to expand the city. Now hills that were covered with wild grass, trees, and footpaths ten years ago are filled with dwellings made of everything from old, reused wood to cinder blocks. Some of the makeshift houses teeter on the edge of eroding hillsides. Others sit comfortably atop carved-out terraces.

On the same day every week, when the sobre ruedas, or street markets “on wheels,” come to the colonias, residents, mostly women and children, come out to shop for meat, poultry, fruits and vegetables. As residents shop, they catch up with one another and with vendors, who bring word of what is transpiring in other colonias. In addition, a good number of the residents that live along the streets where the sobre ruedas set up, display used clothes and appliances from the U.S. in front of their homes for the passersby, in hopes of supplementing their incomes. Others sell gelatins, sweetened ice, and other treats. The practice of supplementing the family income is quite common in working class colonias, and is carried out by both the young and old.

Doña Socorro, a stern elderly woman, supports herself in part by crocheting decorative covers for water gallons. Her deceased husband did not leave her much of a pension given that he worked in the fields of California for many years. Over the last year, Doña Socorro has attended meetings along with others, hoping to gain access to the pension benefits they or their loved ones accrued decades ago while working as field laborers in the U.S. under the bracero program. Yet, unlike the famous coronel that patiently awaited his pension in Marquez’s novel, El Coronel No Tiene Quien Le Escriba, Doña Socorro is not optimistic. As a matter of fact, she believes that there is no pension money for braceros and their families because the U.S. government appropriated it and spent it all.

There are so many people arriving to Tijuana that new colonias seem to appear almost overnight, making it impossible for housing inspectors and city officials to regulate the continuing expansion of the city. Moreover, the opening of a Home Depot in Tijuana this past October is not likely to help matters. However, city officials have recently taken measures—considered drastic by some—to restore some order and to discourage the continual development of the chaotic urban sprawl.

This past August, for example, all 250 homes of the Puerta al Futuro colonia were demolished. Work crews arrived unannounced and, without warning the residents, they began to level the homes. The resident-squatters could only stand by shouting in protest and pleading for compassion as police officers held them back. A small scuffle broke out as a supporter of the residents tried to cross the police blockade. However, police officers quickly restrained the man, and the situation did not escalate.

Authorities claim that Puerta al Futuro was razed as a safety precaution because of the fragility of the homes vulnerable to the annual downpours. Nonetheless, in a matter of hours, the city authorities had effectively rendered several hundred people homeless. Fathers and mothers returned from work that evening to find piles of broken cinderblock, wooden studs, and drywall where their humble homes had stood.

Although the homes had been illegally erected, residents and activists were outraged by the inhumane actions of the city. They raised questions: Why were residents not given prior notice, and why had the authorities suddenly taken such a hard stance against this year-old settlement after residents had invested so much of their income to build their homes? Yet, in the end, their questions fell on deaf ears.

Tourism and the Border Economy

Since the time of prohibition, when businessmen, politicians, and Hollywood personalities traveled to Tijuana to drink and let loose, tourists from the U.S. have considered Tijuana a party town. The influx of dollar-wielding tourists gave rise to bars, clubs, and houses of prostitution, establishments that can still be found in Tijuana. “Vienen a deshogarse,” is what many Tijuanenses say about the tourists, especially the college and high school students who are attracted by the fact that the legal drinking age in Mexico is eighteen. On weekend nights, thousands of college-age men and women converge on La Avenida Revolución, a street in the heart of Tijuana lined with curio shops, bars, and strip clubs.

During the day, La Revolución, or La Revu as locals refer to it, is full of tourists who come looking to purchase “authentic” Mexican cultural items at the curios shops. Like the cab drivers and club greeters, the vendors in these shops and on the street have learned a range of phrases, such as “good price,” in various languages in order to attract the international tourists that make their way down the street. For the most part, the vendors are outwardly pleasant, aware that their livelihood depends on these foreigners. Seeing many of them in action reminds me of what the sociologist Arlie Hochschild refers to as “emotional work,” or the kind of pleasant decorum that workers, such as flight attendants, maintain when interacting with customers.

While many Tijuanenses are unable to cross the Mexico-U.S. border, others do and spend millions of dollars in Southern California shopping at clothing outlets and food wholesalers, among other stores. Children attending schools in Tijuana regularly take school trips to various places throughout Southern California, such as Sea World, the San Diego Zoo, Disneyland, and Magic Mountain. Families living in Tijuana travel to see the San Diego Padres, which advertise discount family packages in Tijuana newspapers.

Moreover, the ever-increasing commercial influence of U.S. firms has brought certain products into Tijuana, thereby enabling Tijuanenses to enjoy aspects of the U.S. without having to cross the border. Throughout the city are fast food franchises, such as Burger King and McDonald’s, as well as Blockbuster video stores and Smart & Final warehouses. The transactions at these establishments, like at other establishments in Tijuana, can be done either in pesos (‘plata’) or dollars (‘oro’). The preference for U.S. currency is evident by this colloquial distinction.

Drugs and Violence in the City

Years ago, at the border, I ran into a man I know, who goes by the nickname Ratón. I was in an air-conditioned car, while the temperature outside had surpassed the 100-degree mark, with the heat and exhaust of hundreds of cars inching their way toward the United States. Ratón was weaving between the cars carrying a plastic bucket filled with sodas in water that at one point must have been ice. Sweat dripped from his face and made his thin white t-shirt translucent. When he saw me through the windshield, Ratón smiled and made his way toward me in the passenger’s side of the car. I rolled down the window and we greeted one another with smiles and handshakes. In the course of our conversation, I told Ratón I was heading to Los Angeles. He informed me that he was sent to the border by his drug rehabilitation center so that he would sweat the toxins out of his body.

The next time I saw Ratón was a few months later. He was not well. Like other addicts in my grandmother’s colonia, he greeted me and asked me for a dollar para curarse. I gave it to him.

Unfortunately, Ratón is not an isolated case. In Tijuana, poverty, violence and drug use are rampant. The level of drug use and violence in Tijuana is unparalleled in its history, in large part because of the presence of the Arellano-Felix drug cartel. More than a decade ago, it began using the city as its base of operation, and over the years, the fledgling cartel has made its presence known with a number of brazen violent acts.

In an effort to counter the drug addiction problem in Tijuana and the surrounding region, state and city officials developed futile solutions. This past summer, for example, the government of Baja California instituted a new ordinance banning narcocorridos (ballads about the lives of drug dealers) from the airwaves. Their decision to prohibit radio stations from carrying this genre of music was, according to government officials, based on their belief that these songs promoted violence and drug use. Yet, residents and visitors of Tijuana can still hear narcocorridos by tuning their radios or car stereos to Spanish language music stations located in nearby San Diego. Additionally, city officials have passed an ordinance prohibiting the sale of drug paraphernalia, such as ceramic pipes, which are sold mostly to tourists. The authorities warned merchants that these items would be confiscated. Nevertheless, the application of this new ordinance is anything but equitable. Law enforcement officials regularly target the wares of the impoverished Mixteco women and children lining the sidewalks frequented by tourists, ignoring the curios shops that prominently display drug paraphernalia by their front doors.

Conclusion

“Tijuana es tan singular como Marsella, Vladivostok, Madagascar or Rio de Janeiro. Un Refugio de Mundos.” With these words, in an op-ed piece in Zeta, architect Diego Maldonado captures the essence of the city in which he resides. Like a picture of someone who looks familiar yet strangely different, Tijuana is both here and there, straddling boundaries—past and present, Mexico and the U.S.—provoking feelings of both comfort and suspicion. As such, it is a city that can easily go unseen by the refugees who visit or pass through it. On the other hand, Tijuana is a place that is lived by those who consider it more than just a pit stop. There is no doubt that Tijuana, a young urban center located along an ancient migratory pathway, will continue to grow as new arrivals build along the folds of its terrain and carve out their own worlds.

Richard Mora is working towards his Ph.D. in Sociology and Social Policy at Harvard University.

Related Articles

Bogotá: A City (Almost) Transformed

The sleek red bus zooms out of the station in northern Bogota, a futuristic symbol of an (almost) transformed city. Nearby, thousands of cyclists of all ages enjoy a sunny morning on Latin America’s largest bike-path network.

Editor’s Letter: Cityscapes

I have to confess. I fell passionately, madly, in love at first sight. I was standing on the edge of Bogotá’s National Park, breathing in the rain-washed air laden with the heavy fragrance of eucalyptus trees. I looked up towards the mountains over the red-tiled roofs. And then it happened.

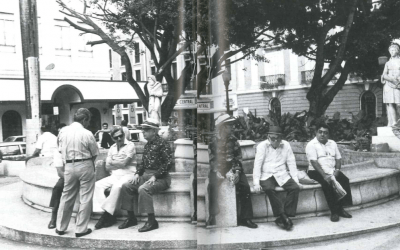

Social Spaces in San Juan

My city, San Juan, is a social city. Its character and virtue are best illustrated and defined by the collective and individual memories of its people and those places where we go to spend time in idleness….