Tropical Interludes

The Role of the Rumbera in Mexican Cine de la Época Dorada

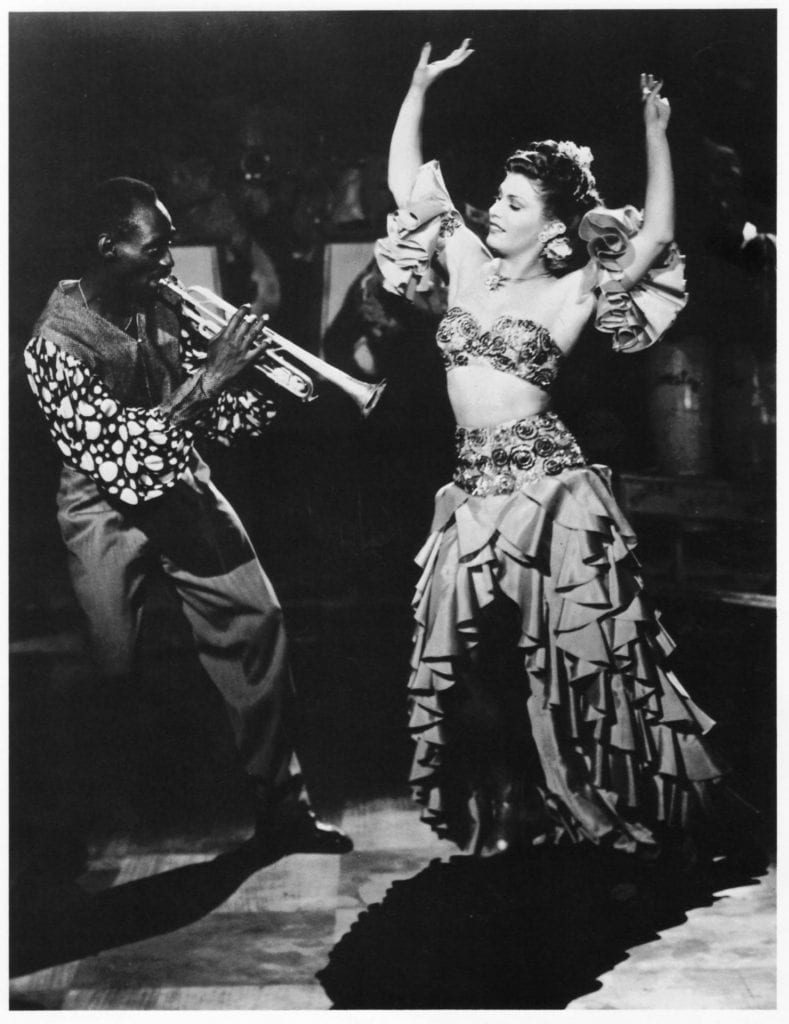

Actress Meché Barba takes cues from her trumpet accompanist in Fuego en la Carne, directed and produced by Juan Ortega in 1949. Photo by Rogelio Agrasanchez

In a popular song from the start of the mambo boom (late 1940s-early 1950s), Cuban musician Benny Moré flirtatiously described the dancing talent of Mexican and Cuban women. He sang in his golden voice, “Pero qué bonito y sabroso bailan el mambo las mexicanas, mueven la cintura y los hombros igualito a las cubanas.” (“Mexican women dance mambo so wonderfully and so full of rhythm, they move their waists and shoulders just like Cuban women.”) Moré first performed the song “Bonito y Sabroso” in Mexico City with the band of mambo king Dámaso Pérez Prado. A few years later, he would travel to Cuba and record the song there. Mambo, a Cuban music and dance phenomenon, had begun to sweep the world in popularity, spreading a fever for the provocative and sensual moves it inspired.

At the same time, another group of women in Mexico—Mexican, Cuban, and American in one case—danced to these Cuban rhythms, receiving almost limitless attention. These women, actresses called rumberas, and their performances live on in a genre of Mexican cine de la época dorada (Golden Age cinema) known as cabaretera films. The cabareteras were popular from the 1940s to the early 1950s. The women take their name as rumberas from the rumba music (Afro-Cuban folkloric music, not the watered down “rhumba” as waltz popularized by Cuban bandleader Xavier Cugat) they danced along with mambo. The films take their name as cabareteras after the cabarets that were the scene of many of their plot lines. With shoulders shaking madly, ruffled sleeves fluttering about, and hips circulating sharply, these rumberas of Mexican cabaretera films burst animatedly onto the cinematic dance floor. Erotic in their dancing, the women acted as translators of the Cuban rhythms.

Meche Barba, Yolanda “Tongolele” Montes, Leticia Palma, María Atonieta Pons, Rosa Carmina, Amalia Aguilar, and Ninón Sevilla, among many others, danced their way across the screen as rumberas; the latter four actually hailed from Cuba. The flourishing of these films, and the centrality of the rumberas and Cuban music, points to a massive influx of Cuban culture at the time. Mambo had arrived with a thunderous growl from the lips of Cuban musician Dámaso Pérez Prado in Mexico City in the late 1940s. Pérez Prado had moved there in 1948, while Cuban singer Benny Moré had come a few years earlier. Both signed contracts with RCA to record and eventually worked together. As Ned Sublette notes in his Cuba and Its Music, the rumbera Ninón Sevilla, from Havana, helped Pérez Prado settle into his new Mexican environment. Pérez Prado and Moré would also appear in a number of Mexican films, set in both Mexico and Cuba. Moré collaborated with Sevilla in Carita de Ángel (1946), and Pérez Prado played the part of an energetic bandleader in Al son del mambo(1950), in addition to other cinematic appearances within the cabaretera genre.

Benny Moré sang in Mexico City cabarets that used to host the actresses and dancers known as rumberas before their leap to the cinema screen in the cabaretera films. Scholars acknowledge the film La mujer del puerto (1934) as a forerunner to the genre, and the films Salón México (1949) and Aventurera (1950) as the best known. Other titles in the genre indicate the films’ central concerns: En carne viva, Mujeres sin mañana, Coqueta, Perdida, and Dicen que soy mujeriego, to name a few. As the titles relate, most of the films concentrated on sex and relations between men and women. In the films, the rumbera often played the role of a troubled young woman down on her luck who most likely survived by prostituting herself. The plot lines of these films varied, which in turn influenced the nature of the rumbera performance. On occasions, she danced in bars or cabarets, where she usually lived under the auspices of a madam. In comparison, a rumbera with bona fide star status danced on a theatrical stage.

Cine de la época dorada may have started in Mexico, but it became widely popular throughout Latin America. As part ofcine de oro, the cabareteras meshed with a music phenomenon that was popular worldwide. (Mambo made its way to the United States, as exemplified in Desi Arnaz of “I Love Lucy” fame plying his musical abilities and heritage into the show. He even starred in a film, Holiday in Havana, crafted around the music.) As compared to other cine de oro films, the cabaretera films played the erotic and celebratory counterpart to popular comedy or drama films, either set on the rancho or in urban locales, starring actors like Cantinflas, Pedro Infante, María Félix, or Jorge Negrete. The plot lines of the cabaretera films largely thrived on the seedy intrigue of sex, dance, excess, and the celebration of music in contrast to the lighter fare of other films of the period. The rumberas performed in this intersection of Cuban music, male desire, personal survival, and a danced choreography.

The rumberas could not have existed without the Cuban rhythms of Moré and many others, usually in the form of the energetic mambo. In the films, the rumbera danced in bars, theaters, and cabarets, unleashing an erotic energy as she translated the language of mambo and rumba to her audience. The staccato rhythm of mambo punctuated the sudden, sensual movements of the dancers, while the addition of fierce rumba rhythms allowed for the interplay of strong, masculine gestures by the women. Backed by a band of musicians and singer (almost always Afro-Cuban musicians) the rumbera became a captivating visual centerpiece of these films. The form of dance in these films elevated the rumbera and allowed for her existence as interpreter and performer, untouchable when she danced.

The place of the rumbera in cinema and in the Mexican national consciousness at this time revolved around the shaping of a sexualized other for the Mexican middle class. These films presented the “tensions in the new social standards of the emerging middle class,” as scholar María S. Arbeláez writes. The rumbera was the central, problematic, and powerful figure in the midst of these cinematic lessons. Her presence also underscored the relative freedom of Cuban sexuality in contrast to the more repressed Mexican counterpart. The sexuality of the rumbera is one that cannot help itself, yet it is a sexuality that is productive through the form of dance. As the boss says to Rosa Carmina’s Maria Antonia in En carne viva, “Tú sabes que cuando bailas, los hombres se despiertan. Te gusta provocarlos.” (“You know that when you dance, guys snap to attention. You like to turn them on.”) Meche Barba’s María Esther makes a similar statement in Humo en los ojos, “Cada vez que un hombre se me acerca, algo pasa.” (“Every time a guy gets near me, something happens.”) In her dance performances, she subverts the male gaze, if temporarily, and with her body makes sense of the musical chaos around her.

As a narrative device in these films, the tropical interludes featuring the rumberas ranged widely. They sometimes provided comic relief to the drama of an intense romance or acted as an elaborate spectacle on a theater stage. In myriad capacities, they always emphasized the particular dancing styles of their protagonists. Viewers would have become familiar with Tongolele’s stern expression paired with lively hips, Amalia Aguilar’s jaunty demeanor and flexible torso, or Ninón Sevilla’s expressive face and stiffer body movements. Whatever their style, the rumberas used it to appropriate the sounds of mambo and rumba, producing their own interpretations and thereby distinguishing their talents. During these dance episodes, other types of music appeared, perhaps a bolero (more often than not penned by Mexican composer Agustín Lara), a Brazilian samba, or a Mexican son jarocho. The exaggerated flair of the rumbera, however, contrasted starkly with the demurely dressed Mexican dancers of a son jarocho. If performing an elaborate number, the rumbera would appear accompanied by all manner of dancers, in costumes ranging from superheroes to “types” of people (like an African “native”) to fantastical creations seemingly without origin.

The rumbera performances to the modern viewer border on the ostentatious, a fact that leads film historian Ana M. López to declare that with the figure of rumbera Ninón Sevilla, the cabaretera genre “reaches its zenith and the boundary between performance and melodrama disappears completely.” The rumbera emotes and exaggerates and translates mambo and rumba into something palatable to the audience widely consuming these films. The rumberas ranged in dancing ability, with some more authentically interpreting the form of Afro-Cuban folkloric movement that influenced the dances. Interspersed in her mambo movements, and following the musicians who accompanied her, she sometimes segued into rumba dancing. The conga drummers signaled this change, increasing their beats to a frenetic pace.

While mambo was energetic and playful, the rhythms of the rumba complex—three varying rhythms known as guaguancó, columbia, and yambú—called for distinctly different dancing. Columbia, usually performed by a solo male dancer as a way to display his physical agility, calls for fierce and abrasive movements that the rumbera danced accordingly. In her rumba dancing, she danced both the columbia and added guaguancó movements, a dance traditionally performed by a couple. The guaguancó dance revolves around the man’s trying to surprise the woman with his pelvic movements, resulting in a surprise thrust in her direction. (In the films, the rumbera would dance the woman’s parts of the guaguancó.) The rumbera may have changed from male to female roles in dance, but the lyrics of the mambo and rumba songs served to reinforce the rumbera’s desirable nature. In Al son del mambo, Amalia Aguilar sings, “Soy la sabrosura del solar, abrazo a toda la gente con mi fuerza tropical…sabrosura tengo yo pa’ regalar.” (“I am the sexiest one in the neighborhood, I embrace people with my tropical flavor…I have enough to give away.”)

On other occasions during a rumba interval, the rumbera switched into another vein entirely and incorporated the gestural idioms of dances for the orishas, the deities of Cuban santería. During a dance scene from Humo en los ojos, Meche Barba’s Mercedes channels the deity Yemayá, goddess of the ocean, through wide, circular movements with her arms. The emotional frenzy associated with her dance performances may blur the lines between the dramatic intent of the rest of the film. However, they reinforce her ability to be a conduit for the culture and beliefs, most likely, of those musicians who play alongside her. In this temporary position, which usually vanishes by the end of the film, when the rumbera confronts her romantic destiny or lack thereof, she gives a voice to someone other than herself.

If not in a theater, the rumbera always circumscribed her presence wherever she performed. She clearly defined her stage, circling either the bar or cabaret floor and denoting her performative space as opposed to other areas of the locale. Marking space with her feet or the spinning the ends of her dress into the air, it was always clear where the performative space of the rumbera began and ended. Whenever someone or something encroached on the boundaries of this space, the dance typically stopped, and the music ended. A scene from the Dicen que soy mujeriego, starring heart throb Pedro Vargas, illustrates the nature of these boundaries. When rumbera Amalia Aguilar (as the character Luciérnaga) dances atop a bar and then amongst patrons, an overzealous audience member grabs her and kisses her. Pedro Vargas steps in to wrangle Aguilar out of the clutches of her aggressive admirer. While she may be available for sexual favors for patrons of the bar, when she dances she is untouchable, and her performative space becomes an area that no one else may enter.

The rumbera, then, muddled the line between the socially acceptable and the exotically thrilling for an audience initially in Mexico. During the time of their popularity, Miguel Alemán Valdés served as president of Mexico, a tenure characterized by corruption and the growing problems of urban ills. The prevalence of cabarets in cinema reflected a growing preoccupation with their presence in places like Mexico City and the need for their regulation. If the number of cabarets grew wildly during the “unregulated revolutionary years” as historian Katherine Elaine Bliss notes in Compromised Positions: Prostitution, Public Health, and Gender Politics in Revolutionary Mexico City, officials later tried to regulate them, their activities, and their patrons. An attempt to zone the cabarets and brothels in Mexico City ended in 1938, but Mexican cinema continued to indulge itself in the tale of the cabaret and its dancing stars in settings such as Mexico City, Tijuana, and Veracruz. Dancing in real life led some of these women to become cinema darlings through their film roles in cabareteras. Voluptuous Tongolele reportedly first began dancing, at the young age of sixteen, at Club Verde in Mexico City. Meanwhile, María Antonieta Pons married film director and dancer Juan Orol, a regular of the club La Aurora (also in Mexico City).

When the cabaretera genre declined in popularity, the women left an undeniable legacy. In addition to appearing in other non-cabaretera films, they would also find fame again in the world of literature, as poignant cultural references to the power of dance. Iris Chacón, a Puerto Rican cabaretera from the 1970s who followed the model of the original rumberas (albeit in a more explicit vein), appeared in the seminal Puerto Rican novel La guaracha del Macho Camacho, further testifying to the power of the original rumberas. Although fueled by a thrilling eroticism, the rumberas ultimately drew their power through the appropriation of the Cuban rhythms of the day, which they interpreted through a dance all their own.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

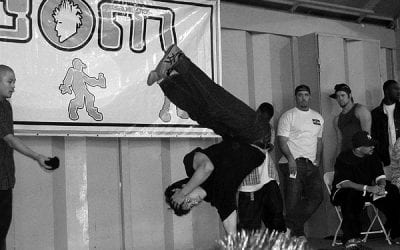

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …