Y marane’ÿ rekávo

Looking for Uncontaminated Water

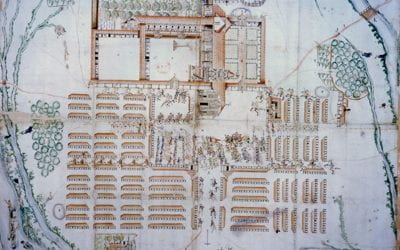

An aerial view of the hydroelectric plant; the Guarani worry about bad waters. Photo courtesy of Oscar Thomas.

It is not only the earth that is filled with impurities. So is the water. Lifeless waters extend throughout the earth, and not only on its surface. Like cholesterol-clogged arteries, contaminated waters also circulate with difficulty deep inside the earth—under the world’s skin.

The search for water will be the quest of many—indeed all— in this 21st century. Where can this clear and crystalline resource be found, these waters of life in the desert, this optimistic and powerful liquid that sings in the creeks and roars in the waterfalls, shining with the brilliance of a diamond hidden in the bowels of the earth?

THE MYTHIC BEGINNINGS

The Guarani, anchored in the future for centuries, believed water to be their place of origin, the center of their earth. We are reminded of the mythic account of the Mbyá, as told by León Cadogan in his book Ywyra ñe’ery: fluye del árbol la palabra (Asunción, CEADUC, 1971, pps. 57-58).

Everything happened in the place

where Our Grandmother lived,

in the Authentic Water.

This happened in our land in

years gone by.

This happened before our land

was destroyed.

(Because today’s earth is merely

a semblance of that earth.)

And Our Grandmother lived in

the future center of the earth.

She held the staff of authority in

her hand as

in our future earth she lived.

She had a son, but she had neither

a father nor a mother.

She gave birth to herself.

Thus, the heart of the earth is water, Y Ete, the authentic water, the true and real water. Water is the heart of the earth; it is where life began. Earth’s life is water. Today, as it happens, this Guarani prophecy has turned into a subject of more prosaic plans, but equally vital for the future, not only for the countries of Mercosur, but of the entire world.

FROM MYTHOLOGY TO A TECHNICAL REPORT

The Guarani territory is home to what is considered the largest aquifer on the planet. The Paraguayan public is perhaps unaware of this fact, but specialists have been well aware of it since the 1970s, and those who engage in geopolitics have probably been negotiating this issue for quite a while. I myself found out about the aquifer quite late and as strange as it may seem, it was through the Guarani of Brazil, who are worried about what is happening to their water and if it will meet with the same sad fate as their land.

So I quote here from a technical report: “The Guarani aquifer is certainly one of the largest reserves of subterranean fresh water in the world with an accumulated volume of 45,000 km3.”

The interesting thing about this enormous wealth is that it corresponds almost exactly to the geographical and ecological limits occupied by the Guarani people prehistorically. It is really just that the water reserve be known as the Guarani aquifer. Cutting across borders, just as the original Guarani territory did, it occupies some 325,000 square miles in Brazil, 87,000 square miles in Argentina, 28,000 square miles in Paraguay and 22,400 in Uruguay. That is, the aquifer is an enormous body whose veins branch out for 463,322,590 square miles. And the waters are so pure that one can drink them untreated because of a natural process of bio-chemical filtration and self-cleaning in the subsoil.

My dear readers, many of you will have noticed that I am quoting a technical report I received from my Guarani friends, authored by the expert Aldo da C. Rebouças, who has written many papers on the subject.

The search for this pure water, this Y Marane’ÿ, truly fills us with admiration, but it also leaves us apprehensive. Who will take ownership of this Genuine Water, this Y Ete from the place of Our Grandmother, which is to say, Mother Water?

The conquerors were always looking for the latest El Dorado wherever they went, if not just over the horizon, then right under their feet. The curious thing is that the discovery of the great aquifer was something of a disappointment; they were looking for oil and only found water. And now the most valuable liquid of the future is that simple water, pure water.

BAD WATERS

Bad waters are what worry the Guarani nowadays. If the land has already been destroyed, isn’t the water next? The risks involving the improper use of subterranean waters are on the horizon. More or less deep wells are already being dug without adequate technology, with the goal of immediate exploitation, exclusive and self-interested use that sucks up enormous quantities of this precious water, turns it into soft drinks and beer and sells it on the market. And the pollution of the upper aquifer, already quite affected by this extraction, could easily contaminate the deeper levels.

The treatment of the waters of the Guarani aquifer has been relatively good until now, but for how long? Speculators and businessmen can set up a system of water trafficking—with its parallel to drug trafficking—that would mean death to the life that comes from the Genuine Water, the Y Ete of the Guarani people.

The Guarani aquifer is a true bank of water of countless value that cannot be wasted nor left in the hands of unscrupulous agents. It is a deposit of extremely high value that should be protected and ethically administered.

“The accumulation of urban and/or industrial residues without adequate technology, as well as the uncontrolled and increasing use of modern chemical components in agriculture, are potential sources of contamination of the subterranean waters. It must be remembered that pollution reaching the ground level or superficial waters can reach deep aquifers or can be confined, depending on the degree to which deep wells continue to be built, operated or abandoned without adequate technology,” warned Brazilian groundwater expert Aldo da C. Rebouças.

The ethical and political implications of this situation cannot be overlooked. Water is no longer a free good that anyone can use arbitrarily; it is a natural resource with social and economic value—and the groundwater even more so than the surface water supply.

Looking for a tierra sin mal—a land without evil—the Guarani found this Y Marane’ÿ, an unexplored, deep, transparent good that bestows life, clarity and goodness, always and whenever it continues to being y sakä (transparent water), and satï (clear water), and porä (good water), and ete (true and genuine water).

This place of flowing water is rightfully known as the Guarani Aquifer. Its brilliant and appropriate name should not be stained with the evils of capitalist contamination and self-interest.

Y marane’ÿ rekávo

En busca del agua sin males

Por Bartomeu Melià, S.J.

Una vista aérea de la central hidroeléctrica; los guaraníes se preocupan por las aguas malas. Foto cortesía de Oscar Thomas.

No solo la tierra ya se llenó de males. También el agua. Las aguas muertas se extienden por la tierra y no solo por su superficie; a manera de venas colesterolizadas, circulan con dificultad bajo la piel del mundo.

La busca del agua será en este siglo XXI el gran afán de muchos, sino de todos. ¿Dónde hallar este bien claro y cristalino, esas aguas de vida en el desierto, ese líquido alegre y poderoso que canta en el arroyo, ruge en la catarata y tiene su brillo de diamante escondido en el seno de la tierra?

OBERTURA MÍTICA

Los Guaraníes, instalados desde hace siglos en lo porvenir, hicieron del agua el lugar de su origen, el centro de su tierra. Recordemos el relato mítico de los Mbyá, tal como lo trae León Cadogan, en el libroYwyra ñe’ery: fluye del ábol la palabra (Asunción, CEADUC, 1971, págs. 57-58).

Todo esto sucedió en el lugar

donde vivía Nuestra Abuela,

en el Agua Genuina.

Esto fue en nuestra tierra

antiguamente.

Esto fue antes de que la tierra

se deshiciera.

(Pues esta tierra de ahora es un simulacro

de aquella tierra).

Y Nuestra Abuela vivía en el fururo centro de la tierra.

Tenía una vara insignia en la mano,

en nuestra futura tierra ella vivió.

Tenía un hijo, pero ella

no tenía padre no tenía madre.

Por sí misma se dió cuerpo.

El centro de la tierra es pues el agua, el Y Ete, el agua auténtica, la genuina, la verdadera. El agua, el centro de la tierra. Ahí es donde comienza la vida. La vida de la tierra es el agua. Ahora bien, esta profecía guaraní hoy se convierte en objeto de planes aparentemente más prosaicos, pero igualmente vitales para el futuro, no solo de los países del Mercosur, sino de todo el mundo.

DE LA MITOLOGIÍA AL INFORME TÉCNICO

Todavía no ha trascendido al gran público en el Paraguay, pero los especialistas lo conocen bien desde la década del 70 y los geopolíticos probablemente ya llevan tiempo negociándolo. En la tierra guaraní está el que se considera el mayor acuífero del planeta. Yo lo he llegado a conocer muy tardíamente, hace poco y por extraño que parezca, precisamente a través de los indios Guaraníes del Brasil, que están preocupados con lo que va a ser de su agua, y si no tendrá el mismo triste destino que ya tuvo su tierra.

Copio de una nota técnica: “El Aquífero Guaraní es ciertamente uno de los mayores reservorios de agua subterránea dulce del mundo, cuyo volumen acumulado se estima en 45.000 km3”.

Lo interesante de esa enorme riqueza es que tiene casi los mismos límites geográficos y ecológicos que tuvo la ocupación prehistórica del pueblo guaraní. Es realmente de justicia que se le denomine como Acuífero Guaraní. Transfronterizo, como lo fue el territorio guaraní originario, tiene una extensión actual de unos 840.000 km2 en el Brasil, 225.000 km2 en Argentina, 71.000 km2 en el Paraguay y 58.000 km2 en el Uruguay. Es decir, un enorme cuerpo cuyas venas se ramifican por una extensión de 1,2 millones de kilómetros cuadrados.

Y son aguas tan puras que pueden ser consumidas sin necesidad de ser tratadas previamente, dados los mecanismo de filtración y autodepuración bio-geoquímica que se dan en el mismo subsuelo.

Mis queridos lectores se habrán dado perfecta cuenta que estoy copiando lo que encuentro en la nota técnica que me facilitaron mis amigos guaraníes y que es de la autoría de un gran especialista en la cuestión, Aldo da C. Rebouças, quien cuenta con numerosos estudios sobre el tema.

La busca de esa agua sin mal, ese Y Marane’ÿ, en realidad nos llena de admiración pero nos deja aprehensivos. ¿Quien se hará dueño de esa Agua Genuina, de ese Y Ete, del lugar de Nuestra Abuela, que es como decir la Madre Agua?

Los conquistadores de siempre la buscarán como el último El Dorado que se sitúa, no en el horizonte, sino debajo de nuestros pies. Lo curioso es que el descubrimiento de ese gran acuífero se debió en gran parte a una decepción; se buscaba petróleo y sólo se encontró agua. Ahora resulta que el líquido del futuro más estimable, es esa pura agua, agua pura.

EL AGUA MALA

Ahí es donde los Guaraníes también hacen escuchar su preocupado llanto y sus endechas. Si la tierra ya fue destruida, ¿no será destruida también el agua? Los riesgos en el mal uso de las aguas subterráneas ya se avizora. Se excavan pozos, más o menos profundos, sin tecnología adecuada, con una explotación inmediatista, un aprovechamiento interesado y exclusivo que chupa cantidades enormes de esa hermana agua para disfrazarla de gaseosa o cerveza, y venderla. Y la polución de acuíferos superiores, ya bastante afectados, podrá fácilmente repercutir en la contaminación de los más profundos.

La renovación de las aguas del Acuífero Guaraní por ahora es bastante buena y satisfactoria, pero, ¿hasta cuándo? Especuladores y negociantes pueden instaurar un aguatráfico que será la muerte de la vida que viene del Agua Genuina, del Y Ete de los Guaraníes.

El Acuífero Guaraní es un verdadero banco de agua de valor incalculable que ni se puede desperdiciar ni debe ser dejado en manos de agentes inescrupulosos. Es un banco de altísimo valor que debe ser protegido y administrado éticamente.

“El depósito de resíduos urbanos y/o industriales sin tecnología adecuada, así como la utilización descontrolada y creciente de insumos químicos modernos en la agricultura, son fuentes potenciales de contaminación de las aguas subterráneas en general. Hay que recordar que la polución que alcanza las aguas subterráneas rasas o freáticas, podrá ser llevada a los acuíferos profundos o confinados en la medida en que los pozos profundos continúen siendo construidos, operados o abandonados sin tecnología adecuada”, nos advierte Aldo da C. Rebouças.

Hay un aspecto ético y político que no puede ser dejado de lado. El agua ahora ya no es solo un bien libre del cual cada uno puede disponer arbitrariamente; es un recurso natural de valor social y económico. y el agua subterránea todavía más que las aguas superficiales.

Buscando una tierra sin mal, los Guaraníes encontraron también ese Y marane’ÿ, un bien recóndito, profundo, trasparente, que nos legaron como lugar de vida, de claridad y de bien, siempre y cuando continúe siendo y sakä (agua transparente), y satï (agua clara), y porä (agua buena), y ete (agua verdadera y genuina).

Este lugar de las aguas surgentes se llama, y con razón, Acuífero Guaraní. Su nombre brillante y apropiado no debe ser manchado con los males de la polución capitalista e interesada.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Bartomeu Melià, S.J., is a Jesuit historian, anthropologist and linguist who focuses on the Guarani people. His work involves the study and the protection of the Guarani language, as well as advocacy for its use.

Bartomeu Melià, S.J., es sacerdote jesuita, antropólogo y lingüista que se enfoca en los Guaranies. Su trabajo incluye el estudio y la protección del lenguaje Guarani.

Related Articles

Jesuit Reflections on their Overseas Missions

When you think of Jesuits in their missions around the world, you—the casual reader—might not think of Plato or ancient Greek authors. Yet two of these…

Paraguay: Un país en una lengua misteriosa y singular

English + Español

If you arrived in a country where almost 90% of the inhabitants speak Guarani, an official and national language along with Spanish but do not identify themselves as “Indian” or aboriginal…

Territory Guarani: Editor’s Letter

DRCLAS receptions are bustling affairs, sparkling with ample liquor, Latin American tidbits and compelling conversations. It was at one of these receptions that Jorge Silvetti and Graciela Silvestri first approached me casually regarding an issue about the Guarani…