Yacyretá

Building the Future

A hydroelectric plant is about much more than water and energy. It is about community and environment, urban planning and resource development. It is about the future and the past of the surrounding area.

In 1973 the governments of Argentina and Paraguay signed the Treaty of Yacyretá to build one of the world’s most important hydroelectric power plants on the Paraná River, the fastest-flowing large river in South America.

The option for a hydroelectric plant was clear: oil, used as a fossil fuel, had to be replaced by a renewable source.

As I am myself an architect from the province of Misiones, in Argentina, I was determined to take advantage of the development of the hydroelectric plant to transform, in a positive way, the situation of those who would be affected and to improve the urban planning for the region’s most important cities and the surrounding area.

The actual construction of the power plant took 34 years, from 1978 to 2011. Finally inaugurated in 1998 with a reservoir level seven meters (7.65 yards) lower than originally designed, the plant was producing only 60% of anticipated energy. A number of engineers and architects focused on achieving the maximum production of electric energy. At the same time, they had to ensure the adaptation of the inhabitants affected by the new reservoir level. All this took place in the Argentine provinces of Misiones and Corrientes and in the Paraguayan departments of Itapuá and Misiones. The reservoir area would encompass 1,500 square kilometers (nearly 590 square miles).

Yacyretá had already built an important bridge linking both countries over the Paraná River. However, the transformation of the surrounding region was still pending. The nearby cities had experienced accelerated growth without any urban planning. Some 700,000 inhabitants—especially the 80,000 who lived in the coastal regions under unsanitary conditions and recurrent floods— would have to be taken into account with the flooding of the reservoir. The environment would undergo changes that would alter its equilibrium.

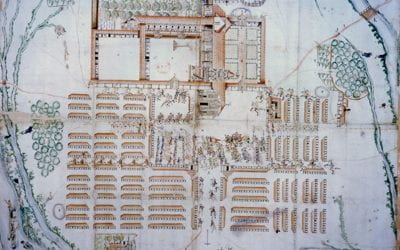

I felt compelled to come up with possible solutions. Perhaps, being from Misiones, I was especially sensitive to the importance of the rivers—their historical, as well as environmental, importance. During the 17th and 18th centuries, the Jesuits and the Guarani-speaking indigenous peoples built more than thirty urban settlements supported by the rational exploitation of water, land and cattle-raising. The streams provided the water they needed for their own consumption and served for fishing, boating and as an energy resource for water wheels and hydraulic mills. I thought that history was not only memory but also a fund of experiences that could serve us now and in the future.

We had to come up with solutions for the high energy requirements of both Paraguay and my country. Completing the reservoir would provide it. The adequate functioning of the Yacyretá undertaking would be the guarantee for the necessary investments for the region.

My home province is a land of rivers and streams, the red soil and the jungle. No element from that habitat could be damaged. Maintaining the quality of the water would be one of our most important objectives.

Nature has returned to the area of the hydroelectric plant. Wood storks and other birds grace the landscape of the Iberá estuary. Photo courtesy of Oscar Thomas.

Some 1,500 square kilometers were set aside as ecological reserves to compensate for the land flooded by the dam for the Yacyretá hydroelectric plant. Actions centering upon the aquatic environment involved monitoring with an eye towards conservation, as well as building capacity for local and regional governments to do the same. We can now contemplate environmental sustainability in the context of a new balance, with images of a neotropic cormorant (Phalacrocorax brasilianus) feeding on the common armado fish (Pretodoras granulosus) and several other Paraná tiger fish found in the vicinity of the dam. Nature has returned. Storks and tuyuyú birds known as American wood storks (Mycteria americana) grace the landscape of the Iberá estuary. All the actions carried out for environmental preservation are carefully explained to all the region’s communities.

The past of this region was always present as an element of identity. At the Ayolas museum, we displayed the archeological pieces found during the earlier explorations for the development of the hydroelectric plant. The Guarani and Kaingang indigenous groups had left traces of their ways of living and teachings to connect us with nature.

But my concern was not only the past; it was the future. The cities in the region had to be renewed. In Paraguay, Ayolas, Santos Cosme and Damián, San Juan del Paraná, Carmen del Paraná, Cambyretá and Encarnación were about to experience changes. In Argentina, the cities of Ituzaingó, Posadas, Garupá and Candelaria would form part of the project. Each would undergo urban reform plans jointly agreed upon with local governments that would integrate the different sectors of the city. Various enclaves were separated not only by streams but by the absence of the necessary road infrastructure. By constructing bridges and providing roads, we would transform vehicle circulation and the means of transport.

A bird swoops to catch a fish in the vicinity of the hydroelectric dam. Photo courtesy of Oscar Thomas

There were other challenges to ensuring future growth. Renovation and improvements had to be provided to hospitals, schools, public administration, security and services; likewise, recreational areas, parks and squares and riverside promenades had to be developed.

Thus, a new connection could be formed with the landscape and, especially with the Paraná River. The result would be the formation of urban coastal areas with access to the water for all.

The city would be thought of as a whole, a living, growing organism.

The population affected by the Yacyretá undertaking received social and health assistance programs. People were moved to housing developments, harmoniously integrated into the city that offered infrastructure and community services. Members of indigenous communities were provided with property titles to well-constructed homes, as well as bilingual schools and social services.

All the cities in the project expanded towards the river. Encarnación has become a river resort; Posadas has considerably increased its number of tourists. The urban and rural sectors now have a better access to the cities after the construction of roads and bridges across streams.

Looking back over the changes that have taken place over a decade, I believe that the Yacyretá hydroelectric undertaking has had strong regional impact. The best way of making the most of its construction and energy production was to see the project as a way to improve the living conditions of all the people in the region by providing the vital infrastructure. That infrastructure would have been impossible to achieve without the hydroelectric sector.

Urban and rural communities have better access after the construction of roads and bridges. Photo courtesy of Oscar Thomas.

For future hydroelectric undertakings in the region, we will have to bear in mind the past experiences. Only if we integrate the necessary projects to improve the daily lives of the residents will we find support for the construction of these new works. And only with these new projects will we find adequate renewal energy for the area and beyond.

Yacyretá

Construyendo futuro

Por Oscar Thomas

En 1973 se firmó el Tratado de Yacyretá entre Argentina y Paraguay. Se procuraba construir una de las más importantes centrales hidroeléctricas de llanura del mundo sobre el río Paraná, el más caudaloso de América del Sur.

La opción por una hidroeléctrica era clara. Se entendía que el petróleo, como combustible fósil, debía ser reemplazado por una fuente renovable.

La etapa de construcción de la hidroeléctrica pudo concluirse con mucho esfuerzo. Se logró tras 34 años de trabajos en el periodo de los años 1978 al 2011. La obra fue inaugurada en el año 1998 con un nivel de embalse de 7 metros por debajo de su nivel definitivo de diseño, produciendo el 60% de la energía prevista. Solucionando esta cuestión se lograría la producción máxima de energía eléctrica. Resolver la problemática requería la realización de una cantidad importante de obras de ingeniería y de arquitectura cuyo objetivo sería posibilitar, en principio, la adaptación del hábitat de los pobladores de la región circundante al nuevo nivel del embalse. Se trataba de las provincias argentinas de Misiones y Corrientes así como de los departamentos paraguayos de Itapuá y Misiones. El área del embalse alcanzaría 1.500 km2.

Yacyretá ya se había hecho cargo de construir un importante puente sobre el río Paraná uniendo ambos países. Faltaba la transformación de la región circundante. Las ciudades habían tenido un crecimiento acelerado sin ningún tipo de planificación previa, contaban con una población de 700.000 habitantes, de las cuales unas 80.000 personas habitaban las zonas costeras que afectaría el recrecimiento del embalse, bajo condiciones insalubres y con recurrentes inundaciones. El medio ambiente tendría cambios que alterarían su equilibrio.

Soy de la provincia de Misiones, Argentina, y Arquitecto. Me propuse aprovechar la oportunidad para transformar positivamente la situación de esas 80.000 personas que serían afectadas y también mejorar urbanísticamente las dos ciudades más importantes de la región, como Encarnación y Posadas, cuya implantación tenía una vinculación no resuelta con el río Paraná.

Tenía en que sustentar mi accionar. La región tenía una destacada historia de proyectos humanos de relacionamiento con el río. Durante los siglos XVII y XVIII los jesuitas y los indios de lengua guaraní conformaron más de treinta asentamientos urbanos sostenidos por la explotación racional del agua, de la tierra y de la producción de diferentes ganados. Para ello habían dispuesto la utilización de los arroyos para provisión de agua para el consumo, la pesca, la navegabilidad y como recurso energético -ruedas y molinos hidráulicos-. Pensé que la historia era memoria y laboratorio de experiencias.

Había que responderle a Paraguay y a mi país que requerían de mayor producción energética. Terminar la represa sería la respuesta adecuada. Para la región el buen funcionamiento del emprendimiento de Yacyretá significaría la garantía para las inversiones necesarias.

Mi provincia es el agua de los ríos y arroyos, la tierra colorada y la selva. Ningún elemento del hábitat debería ser perjudicado. La conservación de la calidad del agua sería uno de los objetivos más importantes.

Se conformaron 1.500 km2 de reservas ecológicas compensatorias por las tierras inundadas por el embalse del río Paraná. Las acciones realizadas fueron explicadas a todas las comunidades de la región.

El pasado de la región siempre estuvo presente como elemento identitario. En el museo de Ayolas se implementó la conservación de las piezas arqueológicas obtenidas a través de los estudios realizados previamente al desarrollo de las obras. Las etnias guaraníes y kaingang dejaron huellas de sus modos de vida y enseñanzas para relacionarnos con la naturaleza.

Las ciudades de la región serían renovadas. En Paraguay tendrían grandes cambios Ayolas, Santos Cosme y Damián, San Juan del Paraná, Carmen del Paraná, Cambyretá y Encarnación. Por su parte en Argentina formarían parte del proyecto las ciudades de Ituzaingó, Posadas, Garupá y Candelaria. Para cada una de ellas se conformarían planteos de reformas urbanas acordadas con los gobiernos locales, que darían lugar a la integración de los distintos sectores de la ciudad. Se trataba de enclaves compartimentados por arroyos y la ausencia de la infraestructura vial necesaria. Por medio de diversos puentes y grandes avenidas se replantearía toda la circulación vehicular y de los medios de transportes. Se le daría respuesta al crecimiento futuro proveyendo un nuevo equipamiento en el área hospitalaria, la educación, la administración pública, la seguridad y los servicios, y dotando de importantes áreas recreativas, paseos, plazas y costaneras. Se estructuraría una nueva relación con el paisaje y fundamentalmente con el río Paraná. El resultado sería la formación de frentes urbanos costeros. El acceso al agua estuvo a disposición de todas las clases sociales. La ciudad sería entendida como una totalidad.

La población afectada por el emprendimiento de Yacyretá fue atendida con programas de asistencia social y de salud, y trasladados a complejos habitacionales que contaban con todas las infraestructuras, servicios y equipamientos comunitarios, armónicamente integrados a la ciudad. Las comunidades indígenas tuvieron viviendas de materiales duraderos, escuelas bilingües y servicios asistenciales. A todos se les adjudicó la propiedad de la tierra.

Todas las ciudades intervenidas se expandieron hacia el río. Encarnación se ha convertido en la ciudad balnearia. Posadas ha aumentado considerablemente la visita de turistas. Los sectores urbanos y rurales tuvieron garantizados sus desplazamientos a las ciudades mediante la construcción de nuevas rutas y puentes para el cruce de los arroyos.

Revisando todo lo realizado en una década pienso que el emprendimiento hidroeléctrico Yacyretá constituyó un fuerte impacto regional. La única posibilidad de terminar su construcción y alcanzar la mayor productividad energética fue entenderlo como la forma de mejorar las condiciones de vida de todos los habitantes de la región proveyéndolos de una infraestructura que hubiera sido imposible concretarla sin el aporte de la empresa hidroeléctrica. También pienso que en los nuevos emprendimientos hidroeléctricos proyectados para la región deberá tenerse en cuenta la experiencia realizada, siendo así la población apoyará la construcción de estas nuevas obras sólo con la simultaneidad de la realización de las obras necesarias para mejorar el nivel de vida cotidianos.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Oscar Thomas, who hails from the Province of Misiones, Argentina, is an architect and executive director at Yacyretá of the Binational Entity of Yacyretá for Argentina. He is the Argentine President for the Argentine-Brazilian Joint Technical Committee for the Construction of the Hydroelectric Plants in Garabí and Panambí. He has taught at the Faculty of Architecture and Urban Planning of the UNNE of Argentina and at the Faculty of Architecture of the Catholic University of Paraguay.

Oscar Alfredo Thomas es Director Ejecutivo de la Entidad Binacional Yacyretá por Argentina. También actualmente es Presidente argentino de la Comisión Técnica Mixta Argentino-Brasileña para la construcción de las Hidroeléctricas de Garabí y Panambí; y Delegado Argentino de la Comisión Mixta Argentino-Paraguaya del Río Paraná, Hidroeléctrica Corpus.

Related Articles

Jesuit Reflections on their Overseas Missions

When you think of Jesuits in their missions around the world, you—the casual reader—might not think of Plato or ancient Greek authors. Yet two of these…

Paraguay: Un país en una lengua misteriosa y singular

English + Español

If you arrived in a country where almost 90% of the inhabitants speak Guarani, an official and national language along with Spanish but do not identify themselves as “Indian” or aboriginal…

Territory Guarani: Editor’s Letter

DRCLAS receptions are bustling affairs, sparkling with ample liquor, Latin American tidbits and compelling conversations. It was at one of these receptions that Jorge Silvetti and Graciela Silvestri first approached me casually regarding an issue about the Guarani…