About the Author

Julia Smith Coyoli is a Ph.D. candidate in Harvard University’s Department of Government and a former DRCLAS Graduate Student Associate. She studies social policy in Latin America, with a focus on subnational politics, education and Mexico.

Education Reform and Teachers’ Unions in Mexico

Shortly after being sworn in as the President of Mexico in 2012, Enrique Peña Nieto and his administration announced a series of ambitious structural reforms, addressing policy areas such as transparency, energy and education. The quickly approved educational reform included a constitutional amendment granting Mexican children the right to a quality education, expanding the previous right to access education. The president’s administration (with the support of the other main political parties) put forth a series of new laws that, it argued, would help to make this new right a reality. The new laws included changes to the national curriculum and an increased focus on inclusion in the classroom. However, public attention landed primarily on the law that dramatically changed the processes under which teachers were to be hired and promoted, as well as requirements they would need to meet to stay in their current positions.

The reforms sparked widespread teacher protests, beginning in 2013. I was living in Mexico City, where a large number of the protests occurred, at the time. Every week, on my way to volunteering at the Interactive Economics Museum, I would walk past the teachers’ encampment, where protesting teachers stayed for weeks to months.

Teachers expressed a number of concerns about the new laws governing their jobs. The reform stipulated that teachers would be hired and promoted based on their results on a nationally standardized exam. Additionally, teachers already employed would need to pass (in three attempts or fewer) a similar exam to keep their job. This was a change from the previous system, which gave the teachers’ union and the state government a shared role in determining hiring and promotion.

Teachers argued that the evaluations were not a fair or effective measure of their abilities in the classroom. They stated that the content covered by the evaluations was not in line with the training they had received at normal schools, that this type of evaluation does not accurately measure who is a good instructor, and that the punitive nature of the evaluations, particularly the test needed to keep one’s job, created unnecessary anxiety and stress among teachers. Gradually, many teachers acquiesced to complete the evaluations, although some (particularly those in the southern parts of the country, where a dissident teachers’ movement dominates) continued to protest until the next president came to power in 2018 and overturned the reform.

At the time, I was puzzled as to why teachers opposed the reform. Certainly, research would seem to justify the policies; their attention to quality education was in line with the recommendations from organizations like the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF). Recognizing that students across the developing world score poorly on standardized tests, despite increasing access to education, has led these organizations to encourage governments to turn their attention away from getting students into the classroom and onto the degree to which students are learning in those classrooms.

I began to look into the teachers’ opposition to this reform as part of my doctoral studies in Political Science. I learned that the teachers’ resistance was exactly what many political scientists would have expected. The political science literature tells us that teachers’ unions have an interest in opposing policies designed to improve educational quality, since those policies frequently threaten the union’s power, as well as teacher’s job stability. The more I read of this literature, it became clear that the puzzle was less why teachers had taken to the streets in the first place, but rather why some teachers and teachers’ union locals had eventually acquiesced, deciding to comply with and even support the reform.

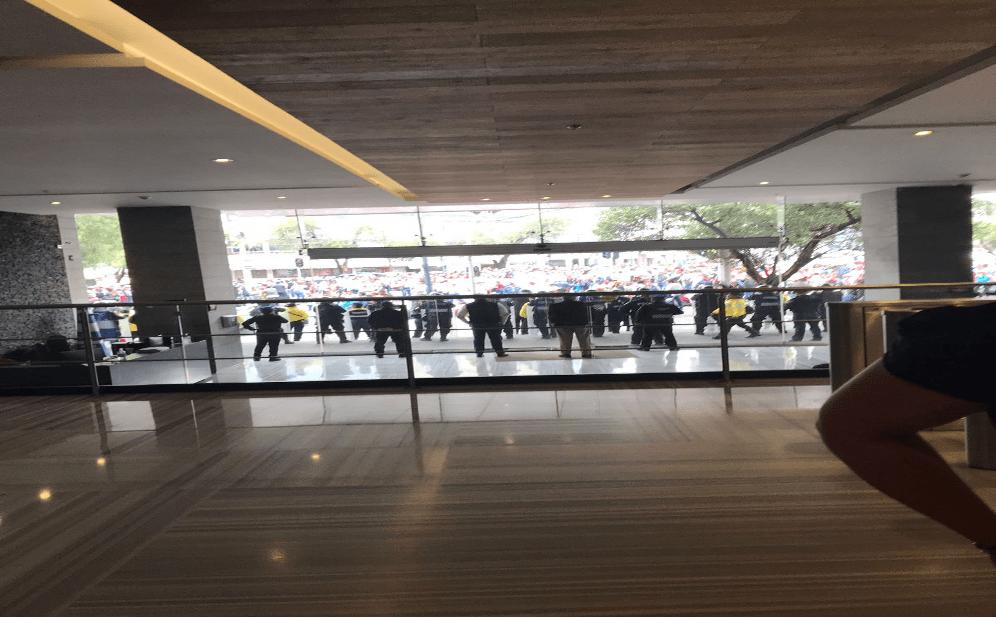

Stuck inside the National Institute for Educational Evaluation (INEE) during fieldwork in 2018, as teachers protesting the education reform shut down the building. Photo by Julia Coyoli.

In my dissertation research I seek to understand how the implementation of this education reform varied at the local level. To understand this variation, I focus in on teachers’ unions and their relationship with local public officials. Given the difficulties inherent in observing and attributing changes in educational quality, there is rarely a coalition of parents or other concerned voters fighting for these policies. This gives the teachers’ union an outsized role in shaping the ways in which educational quality policies are implemented. In Mexico, years of government concessions, such as obligatory membership and dues, have made the teachers’ union (the SNTE) exceptionally strong and an influential player in education policy and politics. The union has also historically utilized its control over teachers’ careers to mobilize them, whether to participate in protest (as in the case of locals aligned with the dissident movement, the CNTE) or as electoral brokers (as in the case of the remaining locals, aligned with the SNTE). The union’s strength stacks the deck even more against reform implementation, as elected officials will be loath to either lose the voters the union can mobilize for them or to incur the ways in which protests disrupt ordinary life.

I find in my research, however, that despite these incentives against reform implementation, there are examples of state-level governments working with the teachers’ union to implement the reform. With the support of DRCLAS, I interviewed leaders of the state-level teachers’ union locals, top bureaucrats at the state-level Ministry of Education and members of the governor’s inner circle in two Mexican states: Coahuila and Oaxaca. Both states have some key features in common. In both, the teachers’ union is strong and has historically dominated education policy. Additionally, both states had governors who wanted to implement the education reform and attempted to negotiate a bargain with the state-level union leadership. But this strategy was only successful in achieving implementation in Coahuila, while implementation remained elusive in Oaxaca.

This variation is surprising. In both states, the teachers’ union had incentives to oppose the reform. In both states, the teachers’ union locals utilized their leverage over teachers’ careers to overcome the collective action problem and generate political influence (whether towards electoral mobilization for certain candidates, in the case of Coahuila, or protest, in the case of Oaxaca). The reform threatened this control, as exams, rather than the union, would determine who was hired/relocated/promoted, making teachers less likely to participate in collective action demanded by their union leaders and reducing union power. Additionally, teachers in both states were worried about the exams and whether their previous education had effectively prepared them to succeed.

In Coahuila, I learned that, beginning soon after the reform was announced, the teachers’ union and the government sat down together to find ways to assuage the union’s (and its members’) concerns about the exams. The government, for example, worked with the union to determine which members were best prepared to succeed on the exams. Those members were assigned to take the exams first, giving less prepared members more time to study. The government also helped finance courses to prepare the teachers for the exams and transportation to and from the exam for any teacher who needed it. To offset some of the losses to the union’s power, the government promised that all school janitors and maintenance staff would be obligatory union members and that the union would continue to have a say over their hiring. The state was willing to negotiate with the union because it was the only path towards ensuring implementation. The state government in Coahuila did not have the infrastructure nor coercive capacity necessary to implement the reform on its own. The union, in contrast, had a structure to reach all of its members, allowing it to easily disseminate this information, convince teachers to change their opinion about the reform and to compel them to participate.

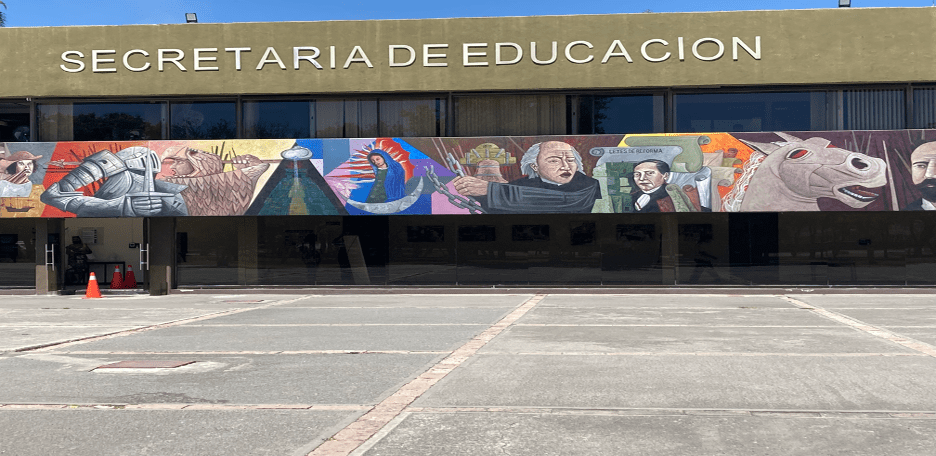

Murals at the Ministry of Education in Coahuila. Photo by Julia Coyoli.

In Oaxaca, I learned that the teachers’ union and the government also sat down together to determine responses to the reform. Initially, the governor supported an initiative designed by the state teachers’ union local to adopt a state-level education policy that did not include any of the standardized tests required by the federal government. Instead, this policy focused on a new curriculum (known as PTEO) designed to teach students knowledge about Oaxaca and its culture, as well as skills to critically engage with a neoliberal world. However, the governor was under increasing pressure from the national government to end the teachers’ protests and obtain their compliance with the reform. In negotiations with both the state and national government, the teachers’ union local in Oaxaca rejected attempts to reach a bargain, including an offer that, if they would stop their protests, the federal government would promise that all Oaxacan teachers would receive immunity from any of the reform’s requirements. In interviews, union leaders from that time explained that they would accept nothing short of the reform’s complete overturn, making a bargain for implementation impossible. As this reality became increasingly clear, the state and federal government used evermore dramatic and coercive methods to attempt to force compliance. Despite the increasing pressure on teachers, in Oaxaca only a small percentage of teachers ever participated in the exams.

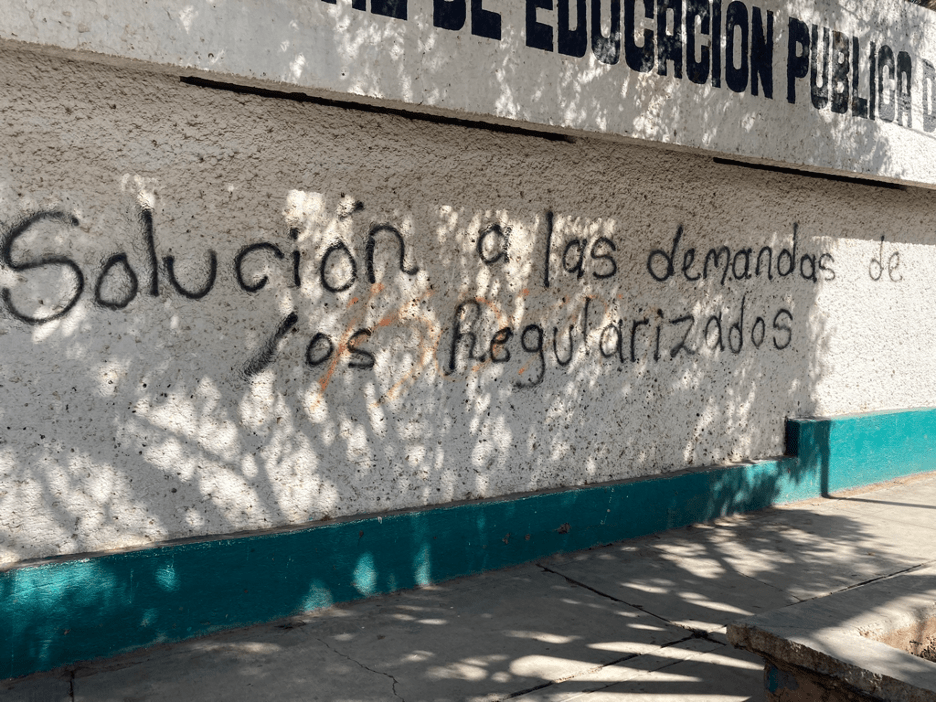

Graffiti outside of the former state-level Ministry of Education in Oaxaca. Graffiti demands a solution for teachers who have worked without pay. Photo by Julia Coyoli.

Given the similar levels of union strength in the two states, I found it surprising that one of them was able to achieve a bargain and implement the reform, while in the other this was impossible. While several factors are likely at play here, I argue in my research that an important one is the role of ideology. In Oaxaca the dissident wing of the SNTE (the CNTE) dominates. This movement is based in a Marxist ideology. As a result, the CNTE opposes neoliberal reforms and policies. It views President Peña Nieto’s educational reform as neoliberal, since the term quality education is rooted not in a holistic understanding of student learning, but rather in an attempt to improve students’ insertion into the job market.

While teachers and the union in both states had material reasons to oppose the reform, ideological opposition was only present in Oaxaca. This additional “cost” made it much more expensive to offer a compelling bargain to the teachers in Oaxaca. However, the fact that we are able to see a bargain in any state goes against the conventional wisdom regarding teachers’ unions. My work shows that teachers’ unions are not always opposed to reform policies and that, if they can be brought on board, they make excellent partners for implementing educational policy, particularly in weak states where their reach and strength can compensate for what the state lacks.

More Student Views

“Yoltajtol. A Word from the Heart”: The Nahuatl Worldview Comes to Harvard

On February 28th, the Moses Mesoamerican Archive and Research Project held the inaugural Nahuatl Workshop “Yoltajtol, A Word from the Heart.” The workshop had the twofold goal of offering an introduction to the Nahuatl language and showing to the participants that Nahuatl is a constitutive part of present-day indigenous peoples’ worldview.

CPR Ambassador Journey

English + Español

One of the simplest yet most effective ways of saving a life in the case of sudden cardiac arrest is cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). It’s an accessible procedure to be trained on, as almost anyone of any age can learn it. Knowing this, and that performing CPR right after cardiac arrest increases survival chances two to three times, why hasn’t everyone been trained on CPR at some point in their lives? (American Heart Association).

Decriminalizing ‘Colonial’ Laws in the Anglophone Caribbean – ‘Buggery’

The moment I stepped foot back on the island, I was no longer the 14-year-old boy who once proudly wore his school uniform to Wolmer’s Boys High School—the oldest school in the Caribbean—and to Maranatha Gospel Hall, my local church. I had become something else entirely in the eyes of the state: a criminal. An illegal presence.