About the Author

Rodrigo del Río is a PhD (c) in the Romance Languages and Literatures Department at Harvard University. He researches the connection between Latin American literature and other social discourses such as economics and politics. He has worked as curator, visual artist and reporter for different institutions and media.

Acerca del Autor

Rodrigo del Río es Ph.D. (c) en el Departamento de Lenguas y Literaturas Romance de Harvard University. Su investigación indaga la conexión entre la literatura latinoamericana y otros discursos sociales como la economía y la política. Ha trabajado como curador, artista visual y reportero para diversas instituciones y medios.

Flowers in the Desert

Rediscovering Chile

Featured photo by Viviana Vilches Wolf/The Clinic

I have many times desecrated the name of my country. Every chance I got, I have recited to different friends Enrique Lihn’s poem “Nunca salí del horroroso Chile” (“I’ve never escaped from horrifying Chile”), in which travels cannot erase the asphyxiating influence of the homeland. Nowhere this pressure feels heavier than in language. Listening far from home, the arrhythmic murmurs of Chilean Spanish awoke in me a profoundly uncanny sensation.

I spent years between failing to hide my accent in Spanish teachers’ modest, deceitfully neutral language and exacerbating its inflections as if the picturesque joke could relieve the discomfort. Both alternatives attempted to establish a limit disguised in the hope of a rupture.

The pandemic brought an abrupt end to this precarious strategy. I was again back home, immersed in my mother tongue. What could separate me now from the fearful prosody? But also, what was I genuinely trying to separate from?

The ghost of Hamlet’s father protests that he died “cut off even in the blossoms of my sins, unhousel’d, disappointed, unaneled,” that is, unprepared, without confession, not having received the eucharist or the extreme unction. His sudden murder deprived him even of the minor joys of repentance.

Contemporary Chilean democracy was born haunted by an even more dangerous ghost. One that was very much alive and could boast that it could not be killed. Dictator Augusto Pinochet resentfully handed over power two years after a failed ambush in which five of his bodyguards died.

As a specter, he could dispense with the body. As an idea, he could live inside our most important national institutions. The 1978 Amnesty Law afforded him an official pardon for his political offenses. The 1980 Constitution assured him a lifetime seat in the Senate, endowing him parliamentary impunity. Differently from Hamlet’s father, our national specter received all the honors. His presence in congress painted the most conspicuous image of our failed democratic transition.

On October 16, 1998, we learned again that Pinochet had a body. The old general was admitted to London Clinic after suffering from a lumbar hernia. That day, Scotland Yard informed him he was being detained. Right-wing politicians took to the streets to protest, barricading streets and threatening to burn down the British embassy.

The following month Patricio Fernández and Pablo Dittborn founded the satirical newspaper The Clinic with the slogan “standing firm next to the people.” The name referred to the modest sign outside London Clinic, where Pinochet spent 503 days detained, waiting for his return to Chile. The slogan was an unearthed journalistic memory, the motto of the leftist Chilean newspaper Clarín, which was shut down after Pinochet’s 1973 coup. The cover exalted the excellent looks of Baltasar Garzón, the Spanish judge prosecuting the dictator. Shallowness acquired political force.

The Clinic confronted the habit of property, decorum and silence that characterized the media during the 90s. It was unbearably irreverent, facing our ghosts, not by the formal rites of an exorcist but the jubilant, campy pose of a ghostbuster.

“We were considered a mixture of terrorists and pornographers,” wrote Patricio Fernández. “What The Clinic continues to combat is the abuse of power.”

The Clinic brought back, after decades of repressed smiles, the long-forgotten habit of laughing out loud at our suffering.

In June 2022, I started writing for The Clinic while participating in the DRCLAS Summer Internship Program. Something had changed, though, in the style I remembered. The magazine declared that they had invented memes, yet it was being replaced by them. The director Macarena Lescornez had confronted the new media ecology upfront and gave more prominence to a combination of digital rhetoric maintaining serious journalism.

Humor was there but laughing was hard.

Chile and the world had also changed. We had experienced continuous protests that were accurately named “estallido social” (social outburst). Political anomie opened the way for a contentious and then failed constitutional process. The pandemic still demanded strict social distancing measures. The Clinic became a place for participating in our fleeting public sphere. Voices, old and new, wrote many of the most polemic op-eds. The magazine also closely reported on the protests and, through its interviews, threaded the precarious fabric of our public space.

That was the magazine I entered under the general editor Patricio de la Paz. A consummate journalist, Patricio was adamant about preserving journalistic rigor. He also had a particular perspective on our country. His book Porfiados (The stubborn ones) narrated the life of Chileans living in extreme regions of the country. His prose has a unique delicacy for illuminating the unlimited richness behind stories that common sense considers banal or precarious. This gaze towards our country became a precious game, like a child in the sea treasure hunting for seashells.

My writing acquired a strange form, not for thinking or communicating but for exploring.

I discovered the deep melancholia lurking in the towns where the train stopped passing. Destroyed by the dictatorship, our railway system lingered in the most intimate memories of those who rode its railcars. In Polcura, a mountain town near the Antuco volcano, Lola Cáceres recalled the destruction of the railway as “traumatic, chaotic” and declared that “to the abandonment that already existed, more abandonment was added.”

I unearthed the stories of people displaced by the industrial transformation of their cities. Ricardo Pérez lived his whole life in Chuquicamata, a company town next to the largest open-pit mine in the world. While working for the private and public copper mining industry, he developed into an eminent musician. He was known as “the trumpet in the desert” and created the band the Copper’sons. Their favorite piece was an upbeat version of Charles Chaplin’s “Smile.” Now Chuquicamata is buried under the dirt produced by the same mining that gave life to the town. Maintaining the population was considered dangerous and expensive. Ricardo still hums his version of “Smile,” while silence is the only music that sounds in old Chuquicamata.

Probably my proudest moment was my piece on young intellectuals. When I arrived in Chile, I felt that our political debate served more as propaganda than as an honest debate of ideas. I uncovered the work of dozens of people under 35, voices usually dismissed by the Scrooge-like hierarchies of our academic institutions.

The Clinic allowed me to hear an outstanding chorus in which a different version of our national history could be told. Language separated me from its overbearing nationalistic tune, not by subtraction but by multiplication. I had found the rhythm of my unhomeland.

I still profoundly admire Enrique Lihn, and I am sure he was wrong. There is a way out of Chile, but inside not outside our borders. And if you take it, you can hear a trumpet singing to the flowers in the desert.

El Ritmo de Mi Apatria

Por Rodrigo del Río

Muchas veces he profanado el nombre de mi país. Recito a mis amigos, cada vez que tengo una oportunidad, el poema de Enrique Lihn “Nunca salí del horroroso Chile,” en el que los viajes no pueden borrar la influencia asfixiante de la patria. Nunca esta presión es más fuerte que en el lenguaje. Oír lejos de casa los murmullos arrítmicos del español chileno despertaban en mí una sensación siniestra.

Pasé años entre el fracaso de esconder mi acento en el lenguaje modesto, engañosamente neutral de los profesores de español, y la exageración de sus inflexiones como si el pintoresquismo pudiera aliviar la incomodidad. Ambas alternativas no eran más que un intento de establecer un límite disfrazado en la esperanza de una ruptura.

La pandemia trajo un fin abrupto a esta precaria estrategia. Estaba de vuelta en casa, inmerso en mi lengua materna. ¿Qué podía separarme ahora de su temible prosodia? Pero también, ¿de qué realmente me estaba tratando de separar?

El fantasma del padre de Hamlet protesta que murió “cut off even in the blossoms of my sins, unhousel’d, disappointed, unaneled,” es decir, sin preparación, sin confesión, y sin recibir la eucaristía ni la extrema unción. El súbito asesinato lo privó incluso de las alegrías menores del arrepentimiento. La democracia chilena contemporánea nació acechada por un fantasma aún más peligroso. Uno que estaba más bien vivo y que podía jactarse de que nadie podía matarlo. El dictador Augusto Pinochet entregó el poder a solo dos años de una emboscada fallida en la que cinco de sus guardaespaldas murieron.

En su calidad de espectro, podía dispensar de las incomodidades de tener un cuerpo. En su calidad de idea, podía vivir al interior de nuestras más importantes instituciones nacionales. La ley de amnistía de 1978 le otorgaba un perdón oficial a sus crímenes políticos. La Constitución de 1980 le aseguraba un puesto en el Senado de por vida, dándole además impunidad parlamentaria. Diferente del padre de Hamlet, nuestro espectro nacional recibía todos los honores. Su presencia en el congreso pintaba la imagen más conspicua de nuestra fallida transición democrática.

El 16 de octubre de 1998, aprendimos una vez más que Pinochet tenía un cuerpo. El viejo general era admitido a la London Clinic después de sufrir una hernia lumbar. Ese día, Scotland Yard le informaba de su detención. Connotados políticos de derecha se tomaron las calles, formando barricadas y amenazando con quemar la embajada británica.

El mes siguiente, Patricio Fernández y Pablo Dittborn fundaban el periódico satírico The Clinic con el slogan “firme junto al pueblo.” El nombre refería al modesto signo que colgaba fuera de London Clinic, donde Pinochet pasó 503 días detenido, a la espera de su retorno a Chile. El slogan era una memoria periodística desenterrada, el lema del Clarín chileno, periódico cancelado después del golpe de 1973. La portada exaltaba la facha de Baltasar Garzón, el juez español que perseguía penalmente al dictador. La superficialidad adquía fuerza política.

The Clinic confrontaba el hábito de propiedad, decoro y silencio que caracterizó a los medios de los 90s. Era insoportablemente irreverente, mirando de frente nuestros fantasmas, pero no a través de los ritos formales del exorcista, sino a través de la pose excesiva y jubilante de un cazafantasmas.

“Se nos consideraba una mezcla de terroristas y pornógrafos,” escribió Patricio Fernández. “Lo que The Clinic continúa combatiendo es el abuso de poder.”

The Clinic trajo, después de décadas de sonrisas reprimidas, el olvidado hábito de reírse a boca abierta de nuestro sufrimiento.

En junio de 2022, comencé a escribir para The Clinic mientras participaba en el programa de pasantías de DRCLAS. Algo había cambiado en el estilo que recordaba. La revista declaraba que habían inventado los memes, sin embargo, estaba siendo reemplazada por ellos. La directora Macarena Lescornez había tomado el reto de integrarse a la nueva ecología medial y dio más prominencia a la retórica digital manteniendo el periodismo serio.

El humor estaba ahí, pero reírse era difícil.

Chile y el mundo también habían cambiado. Habíamos experimentado el ciclo de protestas que se llamó “estallido social.” La anomia política abrió el camino para un contencioso y después fallido proceso constituyente. La pandemia demandaba estrictas medidas de distanciamiento social. The Clinic se convirtió en lugar para participar activamente en nuestra fugaz esfera pública. Voces viejas y nuevas escribieron muchos de los más polémicos artículos de opinión. La revista también reportó de cerca las protestas y, a través de sus entrevistas, tejió la precaria tela de nuestra espacio público.

Esa fue la revista a la que entré bajo el editor general Patricio de la Paz. Un periodista consumado, Patricio era inflexible en preservar el rigor periodístico. Además, tenía una perspectiva particular sobre nuestro país. Su libro Porfiados narra la vida de chilenos viviendo en zonas extremas del país. Su prosa tiene una delicadeza única para iluminar la riqueza ilimitada tras las historias que el sentido común considera banal. Esta mirada sobre nuestro país se convirtió en un juego precioso, como un niño buscando conchitas en la costa igual que si fueran tesoros.

Mi escritura adquirió una forma extraña, no para pensar o comunicarse, sino para explorar.

Descubrí la profunda melancolía de los pueblos donde el tren dejó de pasar. Destruidos por la dictadura, nuestro sistema de ferrocarriles permanecía en las más íntimas memorias de los que anduvieron en sus carros. En Polcura, Lola Cáceres se acordaba de la destrucción del ferrocarril como “traumática, caótica” y declaraba que “al abandono que ya existía le sumaron más abandono.”

Desenterré las historias de comunidades desplazadas por la reconversión industrial de sus ciudades. Ricardo Pérez vivió toda su vida junto a Chuquicamata, la mina de rajo abierto más grande del mundo. Mientras trabajó para la industria minera privada y pública, se desarrolló como un eminente músico. Ricardo fue conocido como “el trompetista del desierto” y creó la banda The Cooper’Sons. Su pieza favorita era una versión zapateada de “Smile,” de Charles Chaplin. Hoy Chuquicamata está enterrada bajo la tierra que extrajo la misma minería que le dio vida al pueblo. Mantener la población en el lugar era considerado peligroso y caro. Ricardo todavía tararea su versión de “Smile,” mientras el silencio es la única música que resuena en el viejo Chuquicamata.

Probablemente mi mayor orgullo es mi pieza sobre jóvenes intelectuales. Al llegar a Chile, sentí que el debate estaba reducido a la propaganda más que al debate de ideas. En una ardua investigación, descubrí el trabajo de docenas de voces intelectuales bajo los 35 años, usualmente descartadas por las jerarquías mezquinas de las instituciones académicas.

The Clinic me permitió oír un asombroso coro en el que una versión distinta de nuestra historia nacional podía ser contada. El lenguaje me separaba de las tonadas nacionalistas, ya no por sustracción sino por multiplicación. Había encontrado el ritmo de mi apatria.

Todavía admiro profundamente a Enrique Lihn, y estoy seguro que estaba equivocado. Hay un escape de Chile, pero dentro y no fuera de sus fronteras. Y si lo tomas, se puede escuchar una trompeta cantándole a las flores en el desierto.

More Student Views

A Shift in Paradigm: Harvard’s Trailblazing Course in the Brazilian Amazon

Former Harvard President Claudine Gay had all it would take to be a tremendous leader of the institution. Her vision, bold humility and intellectual vibrancy were deeply appreciated by the community of university affiliates, as shown by the mobilization of more than 700 Harvard faculty in support of her presidency.

Eyes Closed, Eyes Open: The Puerto Rico Winter Institute

¡Ojos cerrados! On my fifth day in Puerto Rico as part of the 2024 Harvard Puerto Rico Winter Institute (HPRWI), my peers and I went to a workshop at a small but mighty theater collective called Agua, Sol y Sereno.

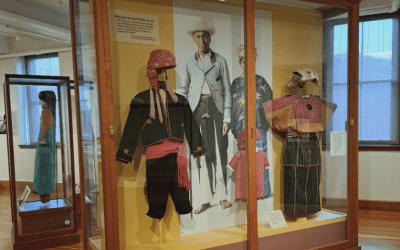

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.