A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC. Bequeathed by the Blisses to Harvard in 1940, the heart of their gift was the collection of art formed over the previous forty years. The donation also included a living collection: the innovative and beautiful gardens designed by Beatrix Farrand. Inside the home, The Blisses had filled their magnificent rooms with an abundance of Modern, Pre-Columbian, Early Modern European, Asian, and Byzantine works of art, although Robert Bliss’s passion was always Pre-Columbian Art.

It was, of course, his Pre-Columbian collection and the scholarship it fostered that brought me to Dumbarton Oaks. I came first as a graduate student in 1985 to hear eminent scholars present their newest research at symposium on Early Ceremonial Architecture in the Andes. The place, the collections and the scholarship mixed in a way that I had never experienced before. The Pre-Columbian collection was and is generative of scholarship in a myriad of ways: groundbreaking research (decipherment of Maya hieroglyphs), award winning publications (most recently The Conquered: Byzantium and America on the Cusp of Modernity by Eleni Kefala) and outreach to Latin American communities (meetings and symposia in collaboration with sister institutions in Panama City, Lima, Bogotá and Guatemala City. for example). I can write this with complete assurance of the generative role of the Pre-Columbian collection because I am the first scholar to be appointed as a Professor of Pre-Columbian Art in the department of the History of Art and Architecture at Harvard and I was appointed with the title Dumbarton Oaks Professor of the History of Pre-Columbian and Colonial Art.

Today, the collections and gardens form the central interests of Dumbarton Oaks, and we therefore host annually some fifty residential scholars in Garden and Landscape, Pre-Columbian, and Byzantine studies based upon these collecting interests. They are joined by musicians and artists from around the world—including many from Latin America— as well as post- baccalaureate Harvard students and post-graduate fellows from Harvard and elsewhere. Amongst other activities, we host symposia, concerts, exhibitions based on our collections and contemporary art instllations in the gardens.

In 1942, Mildred Bliss made it painfully clear the intent of their gift in a letter to Paul Sachs, Robert Bliss’s classmate at Harvard and associate director of the Fogg Museum. She wrote: “If ever the humanities were necessary . . . it is in this epoch of disintegration and dislocation.” By turning over their collections of Europeans paintings, Pre-Columbian, and Byzantine Art as well as their library of rare books, they sought both to preserve them under the care of Harvard as well as to provide the space, time, and resources to further humanistic research in the face of totalitarian non-democratic leaders and institutions. Or as Seneca wrote at the end of De Ira “The breath that we hold so dear will leave us. In the meantime, while we draw it, while we live among human beings, let us practice humanity. Let us not be a terror or a danger to anyone.” Their house and its magnificent gardens were thus intended to provide the future stage where scholars in Pre-Columbian, Landscape and Byzantine studies could pursue their work in idyllic circumstances.

But before it became “a home for the humanities,” Robert Bliss offered Dumbarton Oaks as a neutral site for the allied nations to discuss the world’s future in order to resist the barbaric upheavals of future inhumane instrumentality. Known as the “Dumbarton Oaks Conversations,” representatives from the United Kingdom, The United States, and the Soviet Union met on one day and China the next met in order to give birth to the United Nations. Some sense of a better more humane world was on offer.

Unfortunately, it is, as the great late Yogi Berra would say, “déjà vu all over again” in 2022, or some seventy years since Mildred Bliss wrote to Paul Sachs. Russia, The United States, Brazil, Cuba, Italy, Spain, Venezuela and elsewhere, all have fallen under the sway of what Mildred Bliss and Paul Sachs understood to be the threat of “disintegration and dislocation.” The great hope for the future, as first formed in “the Dumbarton Oaks Conversations” leading to the establishment of the United Nations, has been thwarted by charismatic totalitarians who manipulate their various constituents to disregard working for a better future.

Dumbarton Oaks stands as an institution that is the antithesis of this new barbarianism as it reappears in various parts of Latin America, Europe, Africa, Asia and North America. Formed around the aesthetic and intellectual interests of the Blisses, scholarship and aesthetic experience engage with the past as well as the present through its programming of lectures symposia as well as support for displaced scholars.

The museum does not now actively collect, rather it displays the Byzantine and Pre-Columbian works of art that were acquired by the Blisses during their lifetime together and now open for free admission to the public. The Byzantine and Pre-Columbian collections are in specific galleries while their European and Asian painting and sculpture collection is placed throughout the house. For example, the late Gothic sculpture of the Virgin and Child by Tilman Riemenschneider looks across the Music room of the Main House toward the painting of The Visitation by El Greco. In fact, the spaces of Dumbarton Oaks compose an equally superb collection of exquisite architecture and landscape gardening. McKim, Mead & White took over renovations at Dumbarton Oaks in 1923 and who designed among other elements the beautiful greenhouse as well as the Music room. In the latter, the Blisses and now the Harvard community could and still can listen to chamber music, some of which was commissioned by the Blisses and then by Dumbarton Oaks. Among other works that have been commissioned by the Blisses is Igor Stravinsky’s Dumbarton Concerto.

Dumbarton Oaks has had other buildings designed by world renowned architects such as our new library which was designed by Robert Venturi. The five-story building is so well sited that it seemingly melts into the sloping landscape and is barely visible from the street. The red brick exterior walls are enhanced with Pre-Columbian ceramic motifs formed by using black bricks. Inside are the area collections, the offices for Pre-Columbian, Garden and Landscape and Byzantine fellows and Directors of Studies and library staff. A rare book wing was built earlier in 1964, which contains books and manuscripts in all areas of study at Dumbarton Oaks but is especially focused on Garden and Landscape manuscripts and books based upon Mildred Bliss’s interests. These collections are the heart of our mission as a residential research center in the Humanities. Scholars from or interested in Latin America, find, for example, both rare books and scholarly manuscripts many of which are unavailable for various reason anywhere else, including the digital world. Furthermore they meet and discuss their work from colleagues from all over the world, but most especially from other parts of America other than their own.

The Pre-Columbian Art collection is one of the jewels in the Dumbarton Oak’s crown. The first piece in their collection and which Robert Bliss said opened his passion for collecting is a jadeite figurine from the Olmec culture that was acquired in Paris in 1914. His interest in Latin America was not, however, confined to collecting. In 1935 he spent two months traveling to the Maya sites of Copan, Tikal and elsewhere. Before that he served as the U.S. ambassador to Argentina from 1927 to 1933. His passion for Pre-Columbian art remained constant. In fact, Robert Bliss was contemplating acquiring a small gold pendant the day before he passed away.

Standing Figure, First work in the Bliss Collection Olmec, Middle Preclassic 900 BC – 300 BC 23.81 cm x 12.07 cm x 8.26 cm (9 3/8 in. x 4 3/4 in. x 3 1/4 in.) diopside-jadeite PC.B.014

To house the Pre-Columbian part of their collection, the Blisses commissioned Philip Johnson to design a new modernist wing for the Pre-Columbian collection because for Robert Bliss, his collection was a collection of art works, not to be exhibited in a natural science context. They were to take pride of place alongside their painting of The Visitation by El Greco and the lindenwood sculpture of the Madonna and Child by Tilman Riemenschneider.

- The Visitation by Doménikos Theotokópoulos, (El Greco) ca. 1610 – 1614 96.52 cm x 71.44 cm (38 in. x 28 1/8 in.) oil on canvas HC.P.1936.18.

- Madonna and Child Tilman Riemenschneider ca. 1521 – 1522, 95.25 cm x 35 cm x 21 cm (37 1/2 in. x 13 3/4 in. x 8 1/4 in.) lindenwoodHC.S.1937.06.

The resulting design produced one of the most beautiful buildings in Washington DC and certainly one of the finest exhibition spaces created for a specific collection ever created. It is based upon the circling of a square, eight domed cylindrical gallery rooms, each defined by eight large-scale “columns” and glass walls with an open circular center with a pool. The distribution of galleries allows for a clockwise or counterclockwise circumambulation with a geographic, cultural and chronological ordering. Most important however, is the transparency of the walls that permit the objects to seemingly appear within a natural environment of the garden rather than the cold, neutral spaces of most museums. The integration of space, building materials and works of art is an aesthetic and intellectual joy.

The first curator of the collection, Elizabeth Benson, added to the interior/exterior exchange of light and space by deploying Plexiglas mounts.

Elizabeth Benson and James Mayo mount the Permanent Pre-Columbian Collection in the Philip Johnson Wing, Dumbarton Oaks,1964.

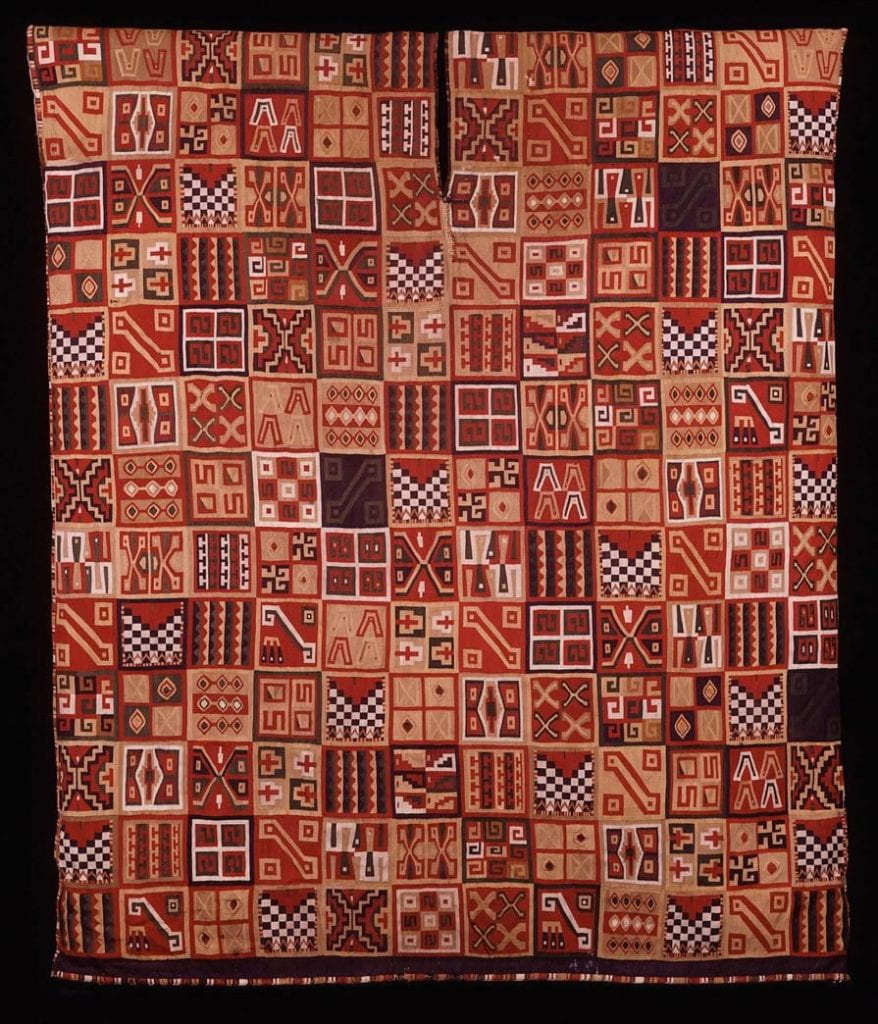

The objects mostly of stone and metal seemed to float in space and they take on an animate spirit as they effortless engage with the gardens outside. The aesthetic harmony achieved between object, space and architecture is unparalleled. Unfortunately, Robert Bliss did not live to see the completion of the project, but the building and the means of display achieved his recognition of and belief in Pre-Columbian objects as things of beauty and great art. He thereby transcended the timeworn notion of such things being in cabinets of curiosity or natural history museums and gave Pre-Columbian works an equal standing with other great artistic traditions. I find great pleasure in seeing children of diverse ancestry whom we bring for classes at Dumbarton Oaks marvel at the works of Pre-Columbian peoples and their equal treatment as the works of other world cultures. Certainly, one of the greatest pieces of art in the Dumbarton Oaks collection is the Inca tunic (uncu). It is a work of art that inspired me in my own path of study. It is not just an object but rather almost a constant companion in my intellectual journeys. As a textile it cannot be on permanent display because it is light sensitive. A tapestry weave of incredible complexity, the geometric abstract design is unique and gives us a very narrow view into a sophisticated artistic tradition unlike any other. A photo can only suggest its magnificence.

One of my favorite pieces on permeant display is also the most widely known piece of art at Dumbarton Oaks. The dating is not precise, but it probably was created in the 19th century. It is a green stone sculpture of the Aztec goddess Tlazolteotl giving birth. She grimaces as she squats holding onto her thighs in the act of giving birth.

- Birthing Figure (Tlazolteotl) Aztec style, Late Postclassic 19th Century (?) 20.32 cm x 12.07 cm x 14.92 cm (8 in. x 4 3/4 in. x 5 7/8 in.) AplitePC.B.071

As in many collections, there are always misattributions and fakes, and this one seems to be one of them. It however has been seen by hundreds of millions of people around the globe when it was copied as the Chachapoyan gold idol in Peru as cast in the movie Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark. There is a certain irony here concerning authenticity, popular culture and exhibitions. It is therefore important to keep such a figure on display as was rightly decided by Juan Antonio Murro, Dumbarton Oak’s chief curator.

Dumbarton Oaks may not now actively collect for the museum; it does bring artists to campus for our contemporary art installation program. There have been six artists who have presented their work in the gardens. The latest work Brier Patch by Hugh Hayden (September 2002 – May 2023) is composed of a hundred school chairs that he has fashioned out of trees from New Jersey’s pine barrens. The branches spring from the writing tablets of the desks that are in fact one and the same, just different parts of the tree, trunk and branch. Some seventy of the chairs are arranged in rows along a part of the garden called “the north vista”. The siting of the piece uses the layout of the “north vista,” a garden room as conceived by Beatrice Ferrand, to visually transform it into a kind of a classroom that visually terminates in a backdrop of living trees. What is conjured up by the Brier Patch are reflections on the nature of education, storytelling and the cultural difficulties that arise through U.S. racial complexities.

Brier Patch, Hugh Hayden, installed on the North Vista, Dumbarton Oaks, 2002.

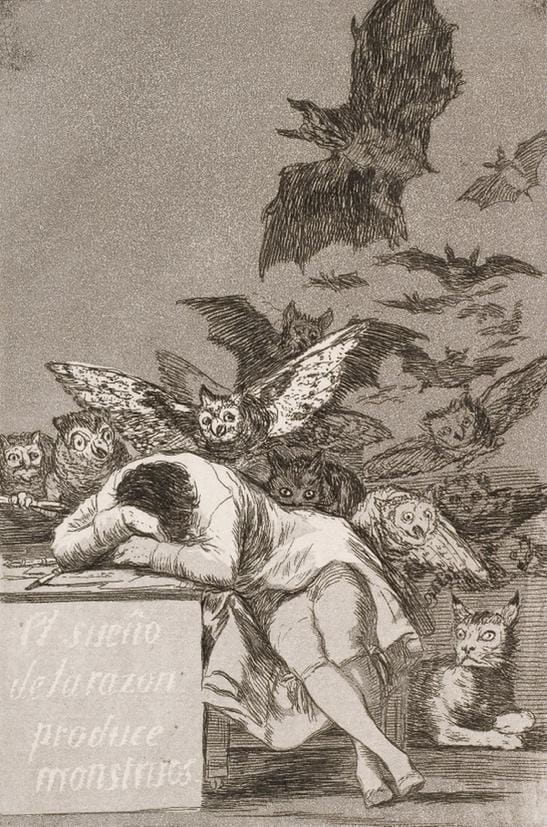

Dumbarton Oaks takes to heart the charge by Blisses when their collections were transferred to the care of Harvard. Dumbarton Oaks is not just a Humanities center, one amongst many others. It was created as a center of the humanities that confronted the inhumanity of a World at War. That moment in history is long gone, but the many of the conditions that brought it about have re-emerged and which require continued confrontation, or as Goya once depicted “El Sueño de Razon Produce Monstros (The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters).

El Sueño de Razon Produce Monstros etching, engraving, drypoint, and burin, 21.5 cm × 15 cm (8+7⁄16 in × 5+7⁄8 in), c.1799 Francisco Goya, Harvard Art Museums.

Thomas B.F. Cummins is director of Dumbarton Oaks. He is also Dumbarton Oaks Professor of Pre-Columbian and Colonial Art Pre-Columbian and Latin American Art in Harvard’s History of Art and Architecture Department.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

“Ahí están los del MoMA”

Curatorial practices have shaped the way we understand modern architecture. Inserted in the spaces of museums, it becomes part of cultural work