Art and Public

The Museum Today

Eugenio Dittborn, 2nd History of the Human Face (Socket of the Eyes), Airmail Painting No. 66, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Margaret Fisher Fund, © Eugenio Dittborn. Image courtesy Alexander and Bonin, New York, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2013.11

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection. Ever since I started my current job in April 2010, I’ve prioritized the art by those from Latin America and by women, as both were under-represented in the museums.

My curatorial predecessor had strenghthened our collections of contemporary art, but key 20th and 21st-century artists from Latin America were largely absent from our institution—a museum known for its important works by renowned artists across the centuries from Europe, the Asian diaspora and the United States.

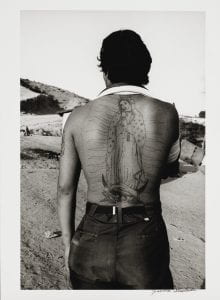

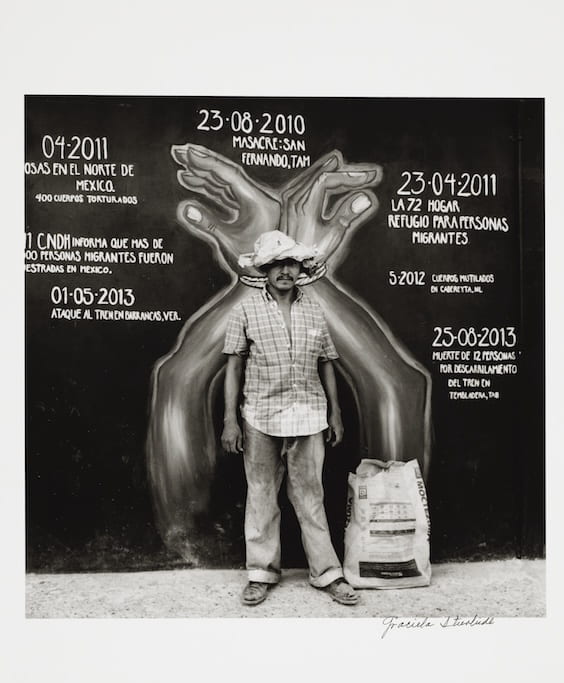

My graduate work at Harvard focused on Latin American art and I welcomed the chance to bring into the collection some of the extraordinary artists from the region whose practices changed the way art was created, perceived, presented and employed within socio-political contexts and well beyond. I acquired major works by Latin American-born artists and organized exhibitions of their work. In addition, I also put an emphasis on outreach, inviting them to lecture and contribute to seminars and to participate in video interviews. I encouraged my colleagues and students to question, learn from and engage with these works from the perspective of their own specializations in German art, photography and the European, American and Asian 20th-century by bringing photographs of immigrants by Graciela Iturbide into dialogue with Candida Hofer’s work recording the Turkish immigrant experience in Germany, or , or Victor Grippo’s Analogia I, 1970-71, conceptual work filled with potatoes, the South American staple, created during the Argentine military dictatorship, placed beside Georg Baselitz’ painting, Saxon Motif, 1964, in which the notion of German homeland is portrayed as the farm, the earth and the bodies who till it.

Graciela Iturbide, La frontera, Tijuana, México (The Border, Tijuana, Mexico), Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Fund for the Acquisition of Photographs, © Graciela Iturbide, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2019.89

Over the last decade, transformational change has begun in museums, , most urgently in the last five years, centering on the very definition of the institution and the role it should play. The American Alliance of Museums recently published a trailblazing report on Diversity, Equity, Accessibility and Inclusion to provide a foundational leadership guide for museums and the International Council of Museums What is a Museum: Perspectives from National and International Leaders (ICOM-U.S. Publication: What is a Museum? August 2022).

Asking these essential questions and making the necessary revisions have been central to curatorial work since 2017, in essence leading to a full-scale re-thinking of why museums exist. We ask ourselves who our audience is and how do we welcome and represent the people and cultures who historically were overlooked, while transparently addressing the ways in which objects were taken from their original homelands and by what means they were acquired and brought into the collections. Most museums have started to discuss the history behind what and why objects were collected, what purpose the collection served, who was represented and who was ignored, and how the story of those cultures was told and to whom. To be clear, it is imperative that these issues are addressed in our world today. The questions raised by this critical reflection crosses disciplines and the history of power and politics within nations, cultures, governments and academic institutions.

In short, a fundamental re-thinking of how an art museum should function and for whom, is at the heart of the matter, and WHO it represents and WHY. The life of an art museum has historically included preserving and caring for art and presenting it to visitors so that they may experience it, by standing beside paintings, sculptures, scrolls, prints, drawings, photographs, stone friezes or jade objects or by walking within an installation of video projections surrounded by images and sounds. However, in order to preserve and care for the artworks housed within, the museum has long been defined by an exclusionary rather than an openly welcoming set of rules. Museum buildings are often monumental in scale/and or appearance, the spaces pristine, guarded and deliberately controlled in terms of light, air, movement and sound. Restrictions are placed on the visitor; touching is not permitted; spaces are to be respected and quiet contemplation is encouraged. I refer to the traditional, historic art museums and their solemnity and grandeur, but in the last decades new spaces for art have been created that are often more physically airy, open and less formidable than the past edifices. However, objects of art remain protected from the viewer with stanchions, pedestals, cases and sometimes motion sensors, keeping the viewer at a remove (except when the contemporary artist seeks the viewer’s direct interaction with the object). But even then, this encouraged interaction is supervised by museum employees charged with protecting the art. (And, of note, many of the museums built in recent decades project a kind of contemporary take on the historic museum building, in that they are monumental statements in stone, aluminum or cutting-edge materials meant to showcase the design achievements of the architect commissioned to create the edifice).

Above all, what art should be inside the museum and how does the setting in which it is presented welcome viewers of all backgrounds? Does the museum create a world apart that, unfortunately, draws a line between those accustomed to entering a monumental, rarefied space and those who see the museum line as a barrier that separates, keeping them outside and excluded? Museum programming with artists and creators/thinkers from across racial and ethnic communities welcomes and erases the sense of the fence that divides the art from the audience. Programming that involves performance, music, spoken word and creative processes with indigenous artists, making pigments, weaving, cutting, pasting, sculpting, dyeing and sewing are ways in which the museum becomes a space for everyone. These programs, tours, wall texts and object labels, publications and online announcements in several languages, besides English, open the museum to an expanding audience, by greeting and encouraging people to come look inside.

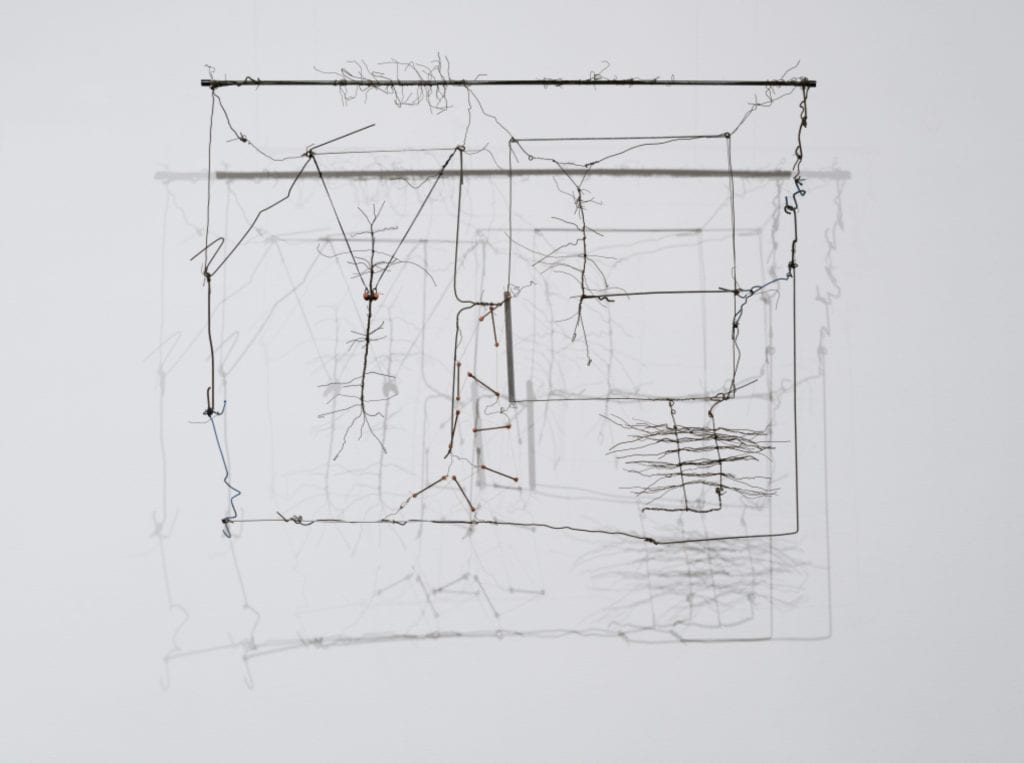

Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt), Drawing without Paper 85/1, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of John Cowles, by exchange; Francis H. Burr Memorial Fund; purchase through the generosity of Charlotte Wagner, and Estrellita Brodsky, © Fundación Gego, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2020.3

As I said, I began this curatorial position focusing on artists from Latin America and especially women, whose work strengthens and amplifies the scope of the history of art told through the Harvard Art Museums collections. Teaching with objects by Latin American artists such as Gego, Doris Salcedo and Clarissa Tossin, known for their sculptures and installations, Leonora Carrington, Eugenio Dittborn and Fernando Bryce whose practices range from drawing, painting, objects and sculptures depending on the artist, as well as by artists from the United States and throughout the world, such as the Palestinian-American sculptor and installation artist Emily Jacir, Nigerian born U.S. based Toyin Ojih Odutola who creates meticulous drawings, African American artist Kara Walker known for her extraordinary reflections on the legacy of slavery through drawings, installations, sculptures and videos, and Choctaw and Cherokee artist Jeffrey Gibson whose sculptures, prints, videos, collages and drawings reflect on the native American experience and oppressive stereotyping, among other artists, allow students and professors to delve into socio-political issues, the human condition, immigration, the environmental crisis, the artist’s hand, use of light, and themes of life and death made manifest through objects.

Gego (Gertrude Goldschmidt), Drawing without Paper 85/1, Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Gift of John Cowles, by exchange; Francis H. Burr Memorial Fund; purchase through the generosity of Charlotte Wagner, and Estrellita Brodsky, © Fundación Gego, Photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College, 2020.3

Since 2010, the scope of the global and the local perspective and who should be represented in our collection has grown and will continue to do so, as it must, in the years ahead. Artists from Latin America continue to be a priority for our collection, but similarly, Latinx artists, Native American Indigenous, African American and the many talented artists from the Asian diaspora, from countries in Africa, eastern Europe and the artists who although born in one nation now live in Canada, Germany, Brazil, Mexico, the United States, Australia, Portugal and other countries, must also be considered on a case by case basis, as hoped for acquisitions.

Today there are more artists than in the past, there is a larger and more robust market for art, and there is a continuing need to bring into our collections a broader representation of artists whose work, in dialogue with other important artists from our times, should fill the walls, cases and galleries. But, from the perspective of my role as Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, the work by each and every one of the artists new to our collection must build upon and strengthen the story of the history of art told by our museums. New works should continue but expand a history that in our collection begins with ancient China, Greece and Rome, through Renaissance Italy, 17th-century Holland, 19th-century France and Japan, the 1930’s social realism of Mexico and the United States and more, as a means of teaching our students and broader audience the role and context of art across centuries and cultures up to the present. Art has served a major socio-political role over time, expressed by not one “approved” voice, but by many. Now more than ever it is essential that we hear, see and share these many expressions from Latin America and Latinx communities and well beyond, or the art museum will become a static rather than thought-provoking space.

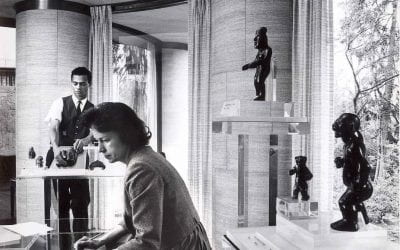

Citation: Walk through of special exhibition “Crossing Lines, Constructing Home: Displacement and Belonging in Contemporary Art” with curators Makeda Best and Mary Schneider Enriquez on September 4, 2019, with Eugenio Dittborn’s 2nd History of the Human Face (Socket of the Eyes), Airmail Painting No. 66 © Eugenio Dittborn. Photo: R. Leopoldina Torres © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

Mary Schneider Enriquez is the Houghton Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, Harvard University. She received her Ph.D. and AB from Harvard. She oversees the museums’ collections of Modern and Contemporary Art. Her scholarly interests focus on 20th- and 21st-century global art, with special emphasis on art from Latin America; art and politics; sculpture and installation; and the work of Mark Rothko. Recent exhibitions have included Mark Rothko’s Harvard Murals (2014–15), Doris Salcedo: The Materiality of Mourning (2016–17), Fernando Bryce: The Book of Needs (2018), Nam June Paik: Screen Play (2018) Crossing Lines Constructing Home: Displacement and Belonging in Contemporary Art (2020) and Krzysztof Wodiczko: Portrait (2021).

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.

“Ahí están los del MoMA”

Curatorial practices have shaped the way we understand modern architecture. Inserted in the spaces of museums, it becomes part of cultural work