“Ahí están los del MoMA”

Translating Architecture to the Museum

Curatorial practices have shaped the way we understand modern architecture. Inserted in the spaces of museums, it becomes part of cultural work. At the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA), it is an ongoing part of the struggles to bring architecture—including in Latin America—to its visitors. Curatorial strategies that expand our notion of “what belongs in museums,” and in which kind of museums—be it art, anthropology or history—help us make cultural work more diverse and inclusive.

Entering the museum, architecture has generally been at a loss. Unlike art, it has been next to impossible to exhibit buildings themselves inside museums. When this happens, as for example when the Lustron House—a post-Second World War prefabricated enameled steel suburban home—was exhibited inside MoMA’s galleries in the 2008 Home Delivery: Fabricating the Modern Dwelling, the uncanny experience made us see this building with fresh eyes. This curatorial strategy of defamiliarization solicits both our physical and intellectual attention in a kind of holistic engagement that addresses the established belief that, if one is to understand architecture, one must experience it in the built environment. After all, one does not go to a museum to see a copy of an artwork, and if a preliminary sketch is on display, it’s often to show it in contrast to the finished and fully realized masterpiece.

Architecture exhibitions go against the grain of this “experiential mandate” as they make us experience architecture through its representation, principally drawings, photos, and models. Curatorial work in architecture can thus be understood as a struggle with representation. Yet it is precisely this struggle over how to re-present architecture that makes it cultural work and not merely the presentation of an object as if there was one essential embodied meaning to capture and display it to the public. Architecture exhibitions necessarily expose the space of the museum as a construction site of culture. This is the benefit of the curatorial struggle with representation. What is being constructed in architecture exhibitions, and how? What is the experience and the knowledge being produced? These are fundamental curatorial questions.The turn to the archive in curatorial practices and the recent problem of the migration of archives make these questions even more relevant and pressing today.

In 2012, I started working at the Department of Architecture and Design of the Museum of Modern Art with the expectation of producing an architecture show that became Latin America in Construction: Architecture 1955-80. The exhibition was generally well-received—although some found the effort, which I would qualify as the monumental, almost quixotic, as perhaps a “little too late,” as Susana Torre contended in “Is MoMA’s First Latin American Architectural Survey in 60 Years Too Little Too Late?” When it opened in March 2015, it had been sixty years since the pivotal 1955 exhibition Latin American Architecture since 1945—a show that marked MoMA’s protracted engagement with the architecture culture of the region since the museum’s founding in 1929. By starting the show in 1955, the curatorial team made a clear statement of institutional redress. This went beyond the architecture department’s turning a blind eye to the region—except for signature shows such as the 1976 The Architecture of Luis Barragán or the 1991 Roberto Burle Marx: The Unnatural Art of the Garden that reveal, if not a sustained interest in the region, certainly an awareness of ongoing developments.

Former MoMA Chief Curator of Architecture and Design Barry Bergdoll seated at the Fundación Rogelio Salmona, Bogotá, Colombia, 2014 Courtesy of the author

A key redress of the 2015 show was the incorporation of the actual materials of architectural production during the period covered by the exhibition. In other words, visitors encountered a constellation of original drawings, photographs and models, along with many sketches, pamphlets, publications and films; in short, a kaleidoscopic assortment of materials produced at the time. One thus encountered historical forms and objects of architectural production that emerged through specific architectural techniques and intentions as a reponse to salient social and disciplinary questions within a region called Latin America.

This curatorial strategy of presenting architecture purposely did not privilege any one medium of representation. It rather sought to activate a constellation of techniques to construct the material culture that enabled the buildings presented. We found that this curatorial strategy brings important pragmatic challenges that institutions like MoMA can best negotiate and—for better or worse—explain their existence. In Latin America in Construction, the archive—so to speak—overtook the traditional exhibition in a rapturous stockpiling frenzy pushed to the point of discursive overdrive and institutional collapse. With close to 500 original works and a total of over 800 physical and digital objects, coming from a plethora of archives from across the Americas and Europe, the exhibition transposed the aesthetics of a period and of works produced in faraway places to the museum gallery. This kind of translation—of trasladar and traducir—acted both in space and time and was a key strategy to constructing Latin America.

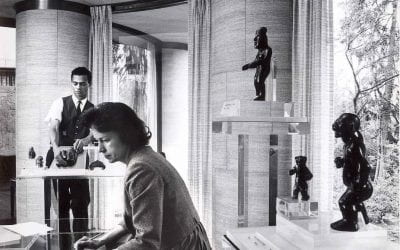

Loly Sanabria and Barry Bergdoll at the archives of architect José Tomás Sanabria, Caracas, Venezuela, 2014 (Today part of the Alberto Vollmer Foundation). Courtesy of the author

The exhibition marked a shift in MoMA’s approach to the region’s architecture, recognizing for the first time its historicity. This turn to history has to do with MoMA’s own historicity (let’s not forget it turns 100 in 2029) and that of the notion of modernism as a global production. Latin America in Construction was grounded on historical research and benefited from the growth and professionalization of architecture archives—not to mention Ph.D. programs that have consolidated research on the history of architecture. The exhibition materialized Latin America as an expansive field of research, as a challenge to and task of architecture history. At the same time, by blurring the line between archive and exhibition, Latin America in Construction revealed how history has become part of a contemporary ritual of cultural consumption and a key instrument in the politics of knowledge production in the 21st century.

Acts of translation are not neutral; they participate and enable a political economy of cultural work tied to systems of social value. This was clear when we traversed the region looking for original materials for the exhibition. We encountered an uneven field of architectural source knowledge that can be parsed into two categories: buildings and archives. Between all four curators—U.S.-born Barry Bergdoll, Brazilian native Carlos Comas, Jorge Francisco Liernur from Argentina and myself (born in Puerto Rico to Cuban refugee parents)—we visited most of the buildings exhibited. Still in use, some were well maintained; many had been transformed beyond recognition, such as the famed 1969 PREVI (Proyecto Experimental de Vivienda) in Lima, Perú, for the better—honoring the intentions of the project to grow with its users. We celebrated this in the exhibition with clips from documentary interviews of residents and local scholars presented in “Previ: 45 Years after its completion” and produced by U.S. architecture students from Landscape + Urbanism Graduate Program of Woodbury School of Architecture. Looking at actual buildings and, in many occasions, meeting and chatting with their users was a unique experience—many were very proud of the buildings in which they lived and worked. A resident of the housing complex Conjunto Habitacional Rioja in Buenos Aires, Argentina, was very suspicious of us looking at the building—mistaking us for foreign developers and gentrifying agents! The recognition that institutions like MoMA bring to works of art and architecture is no minor byproduct of exhibitions and can be instrumentalized for different purposes. The phrase: “Ahí están los del MoMA” (the MoMA people are there), which we overheard countless times throughout our travels, had both a felicitous (we hoped auspicious) and ominous ring to it.

There are many world-class archives across Latin America, both public and private. However, as a whole, this critical site of knowledge—the architectural archive—is in a precarious state. We hoped the exhibition would help underscore the value of architecture archives, many of which remained in private hands, managed by families battling against great odds to preserve what are important legacies of the built environment.

The 2015 exhibition served to increase MoMA’s collection holdings, contributing to the preservation of many works, and enabling a migration of archives and works that perpetuates uneven playing fields. Although it’s important to raise this issue, simplistic and reductive accusations that stir nationalist fires fail to get at the meat of the problem. There is no question that “the region” has seen the flight of important archives, such as those of Brazilian architects Paulo Mendes da Rocha in 2020 followed by that of Lucio Costa’s in 2021, both donated to the Casa de Arquitectura in Portugal, which prompted me to organize the symposium Brazil Speaks: Architecture Culture at Risk in 2022. When it comes to “migrating archives,” Brazil is not alone—the exodus of the Amancio Williams Archive from Buenos Aires, seeking refuge in 2020 at the Canadian Center for Architecture in Montreal, exemplifies this tendency.

Architect Thomas Sprechmann, Patricio del Real, and Barry Bergdoll in the architect’s office, Montevideo, Uruguay, 2014. Courtesy of the author

The “exit” (or perhaps it’s a defection, depending on where you fall on the political spectrum) of architecture archives is, of course, not a new story. The acquisition of the Luis Barragán archive in 1995 to Vitra’s bunker in Switzerland caused great concern. That same year, 1995, Harvard’s Frances Loeb Library Special Collections accessioned the archive of Argentine architect Jorge Ferrari-Hardoy. These two acquisitions, however, are not commensurable: the latter was a gift from the Ferrari-Hardoy family; the former, the acquisition of the entire works of Barragán, was an outright commercial transaction of over $2-million U.S. dollars, according to the Mexican press, that laid claim to the buildings themselves as it sought to trademark and police all future photography of the built works. I’m not launching some kind of “Latin Americanist” or nationalist lamentation against the exodus of archival materials and original works from the region. It is hard to image that there is a concerted effort at cultural spoliation by affluent institutions in the “Global North”—beyond the political economy of neoliberal globalization. Or is there? Here at Harvard, the Ferrari-Hardoy collection is not alone, and is in very good company, residing alongside the entire works of British architects Allison and Peter Smithson and Japanese architect Tange Kenzo—gifted to the Frances Loeb Library in 2003 and 2011, respectively.

Installation of a work by Luis Barragán displayed in Latin American in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980. Courtesy of the author

It’s important to recognize the praiseworthy activity of people and institutions that work very hard on the organization, conservation and dissemination of architecture culture, no matter where they are located. The rising costs of cataloguing, storage and conservation are key factors as to why archives and collections migrate. The lure of digitalization, with the promise of open access to more people, adds new pressures to this ongoing problem. Although well-meaning institutions engage in a practice of cultural democratization, we should not lose sight of the tremendous loss when an archive migrates. The migration or re-location of any archival collections re-positions its meaning and brings serious challenges to underfunded scholars and institutions for which these works become inaccessible. Archives are silent without their use, and who uses them—who has access to them—continues to be a pressing question. What is at stake is the production of knowledge, and who ultimately controls this production.

The void left by the migration of archives may help us become aware of those practices that have left no “official” or institutional archive. These voids speak to the erasure of cultural memory as part of the construction of history. It thus opens the opportunity and the need to reconceptualize the “architecture archive” beyond the collection of disciplinary materials and argues for an expandin and dynamic archiving that decenters hegemonic narratives and exposes the structures of power and mechanisms of control that have shaped the traditional archive. Without disattending disciplinary concerns, we can, at the same time, construct “alternative archives” that go beyond the disciplinary practice of architecture and aggregate diverse actors, spatial practices and forms of presentation that exceed the discipline.

The Ecuación del Desarrollo and other original materials back at their archive in Montevideo, Uruguay. Courtesy Mery Mendez

The migration of archives is also a means of cultural silencing. The myth that these better-funded and name-brand institutions somehow are able to amplify the information contained within an archive is a fallacy. For example, in my extensive research within the MoMA archive, I discovered numerous documents, materials and ephemera that, although preserved, remain buried by what today we call blockbuster shows. Some still remain uncatalogued and, therefore, inaccessible. By working at MoMA, I had the privilege of wallowing in this valuable pile, and in the process catching a bit of archive fever myself. Luckily, I have been able to extract some forgotten and little-known details that I have included in my book Constructing Latin America: Architecture, Politics and Race at the Museum of Modern Art and in subsequent essays to be published on MoMA’s influence in South America, particularly Argentina and Brazil. But it’s only the tip of a massive iceberg.

Installation of the Estadio Mendoza model in Latin American in Construction: Architecture 1955-1980 a work now part of MoMA’s collection. Courtesy of the author

Today the “architecture archive” is an essential component of architecture exhibitions. Exhibitions can reconstruct and deconstruct, assemble, and reassemble. In short, they help us open up architecture and establish new histories. Exhibitions are an integral part of the production of architecture, guiding its practice and stimulating its culture. Through exhibitions, architecture becomes a cultural object that is put on display, revealing the constructed nature of culture. Power relations make their rendezvous in the exhibition space, and the exhibitions act as an instrument or device of cultural power presenting disciplinary knowledges that thread cultural spaces with those of political and economic power. Visiting a museum or gallery, visiting an exhibition, is not a simple stroll in the park: It is a cultural ceremony, a ritual, that gives value to the works exhibited and curatorial activities that shape aesthetic, social and historical narratives. Exhibitions construct a public and insist on understanding architecture as a shared endeavor.

From the perspective of someone speaking from the United States and its elite institutions, we must rethink how we do cultural work in a world fraught with uneven power relations. We must develop new models that allow for an effective multi-centered cultural economy. We must renounce performing the “function of center,” of engaging in cultural extraction and responsively share in the resources that enable the production of knowledge.

Patricio del Real is an architectural historian who works on modern architecture and its transnational connections with a focus on the Americas. His book, Constructing Latin America: Architecture, Politics, and Race at the Museum of Modern Art, examines multiple architecture exhibitions and MoMA as a cultural weapon in the early 20th Century. He is Associate Professor of History of Art and Architecture at Harvard.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.