Animating Peripheries

A View from the Museo del Barro

The Museo del Barro in Asunción immerses the visitor in a collection of images and objects, often in a somewhat disordered fashion, not all categorized or classified in the way such institutions tend to present them.

The Museo del Barro, as the Center for Visual Arts is commonly known, houses collections of Popular Art (the Museo del Barro) and Ethnic Art (Museum of Indigenous Art), as well as several expressions of Urban Art of Paraguay and Ibero-America (the Paraguayan Museum of Contemporary Art).

The visitor might encounter a collection of popular masks, an ample assortment of Franciscan and Jesuit images, striking ceremonial costumes or the impressive selection of Iberoamerican art, including works by Ricardo Migliorisi, Carlos Colombino and Osvaldo Salerno. The temporary exhibits are widely varied, from a showing of some emerging artist to large overview exhibit that bring together different works on document on 19th–century portraiture in Paraguay to a collection of the recent production of the weavers of ao poi, an indigenous cloth that takes its embroidery from the type used on colonial shirts.

The museum has three entrances from a central patio. From there, the visitor can lose herself in a circular game, always returning to the same site. There is more than one way to go through the Museo del Barro; one does not always read from left to right nor begin as focus groups mandate; everything is left up to chance and no particular sequence is required. The museum leaves open the possibility of felt experience, rather than just inform the passive gaze of a directed spectator.

It seeks to erase the distinct ways of classifying art, doing away with the boundaries between the popular, indigenous and urban in Paraguay.

Thus, the Museo del Barro preserves the ambiguity of being a museum without totally being a museum. It attempts to skirt the boundaries of the concept of a museum while at the same time renders this concept ill-fitting and permeable.

It is an art museum as fluid as the definition of art itself, which here has tried to include, in the words of Paraguayan art scholar Ticio Escobar, “the beauty of the other.”

A BRIEF HISTORY

The Center for Visual Arts/Museo del Barro came into being through several initiatives over the course of forty years. What makes it unusual is that it has been created by artists, anthropologists and art critics. Originally, it emerged as a project that would function on the margins of the state and in opposition to its politics.

The Center’s three museums sprang into life independently. However, they eventually came together under one roof as one project. The Center’s roots go back to 1972 with a Circulating Collection started by Paraguayan artists Olga Blinder and Carlos Colombino. As its name implies, the collection did not have its own space and moved from one place to another.

In 1980, a permanent space for the collection was sought, with the Museo del Barro inaugurated in a small house. Artists Osvaldo Salerno and Ysanne Gayet, along with Carlos Colombino, spearheaded the effort. Art historian Ticio Escobar later joined the group. In 1984, the first exhibition space was opened and later developed into the three collections integrating the Center for Visual Arts.

The group had long been interested in popular and indigenous art, inspired by poet and art critic Josefina Plá, a native of the Canary Islands who settled in Paraguay, as well as such important personalities as Brazilian-Paraguayan artist Livio Abramo, Jesuit indigenous rights champion Bartomeu Melià, and Olga Blinder herself.

The treatment of the works in this museum makes it possible for popular and indigenous art to be seen as equal to urban or “erudite” art. The museum seeks to provide a dialogue between these types of art in spite of their differences, striving to undermine the official myth that popular and indigenous art can be reduced to “folkloric,” “authentic,” “vernacular,” “our very own.” That is, popular art can often be trivialized, stripped of its subtleties and differences.

When Ticio Escobar, who has given deep thought to Paraguayan art from this triple perspective (popular, indigenous, urban) in a systematic way, wrote La Belleza de los Otros (1994), he recounts there the foundational story set out in El brazalete de Túkule. Túkule, a powerful Ishir shaman, is delicately making a bracelet called oikakar (created from vegetable and hand-tied, one by one, with small and oversized feathers). Escobar questions why it is necessary to add a line of multicolored feathers to something which appears to have already been finished, and receives this answer: “So that it looks more beautiful.” This bracelet is functional—ceremonial, shamanic and ritual—but at the same time, it is aesthetic: it should attract our attention through its shining beauty.

The language of difference emerged intuitively at the beginning. First came the practice and then the theory; the Museo del Barro followed a path that revealed itself in the middle of the journey. It went about constructing itself in fragments from total chance until it jelled (although it never completely jelled) in one place (actually in two—that of the physical place and its conceptual place).

Paraguayan art finds in the Museo del Barro a space in which we can see ourselves from multiple perspectives, talking to the “we” that in Paraguay means we are two (or at least two, since language always puts that duality in evidence). In Guarani, the language of the majority of the Paraguayan population, there are two words for “we,” one which is inclusive (ñande) and the other which is exclusive (ore). These two ways of saying “we” make up a specific way of understanding identity. If the official culture tries to propagate a unified “national being” through diverse means, the language itself gives the lie to this concept.

DEVELOPING DIALOGUE

The idea of setting up a dialogue and bringing together the artistic productions of Paraguay’s different peoples came about through an unplanned action. While Ticio Escobar was writing Una interpretación de las artes visuales en el Paraguay (An Interpretation of Paraguay’s Visual Arts, published in two volumes in 1982 and 1984), he was faced with the dilemma of how to verbalize these differences and to find a place within an official history that denied these differences.

With his book El mito del arte y el mito del pueblo (The Myth of Art and the Myth of People), Escobar consolidated his thinking about the equivalence of popular and indigenous art alongside so-called erudite art. This analysis laid the foundation for a more conclusive discussion about modernity and also about the nature of the erudite and the popular, no longer facing them off as binary contradictions, but in terms of exploring them and defining relationships. Escobar’s text sums up the vocation of the Center of Visual Arts/Museo del Barro. It departs from art theory to enter into cultural theory with all its political implications: the disputes for the hegemonic control of the symbolic capital of a territory evolved into a nation.

The Museo del Barro significantly adopts the praxis of this text, the theoretical basis that ties together questions that have arisen through doing. This concept of art set forth by Escobar and, by extension, at the museum—this manipulation of material forms that shake up the senses—permits the insertion of the concept of popular art into the writing of another history of art and to begin to dislocate Eurocentric concepts. These new ideas concern the autonomy of art, the concept of contemporaneity and of uniqueness.

ART FOR INDIGENOUS AND PEASANT COMMUNITIES

One of the major discussions regarding the use of the word “art” to talk about the aesthetic-poetic productions of non-Western cultures has to do with a concrete fact. These cultures do not use the word “art” to describe the production of material objects nor, for the most part, do they consider their production to be art.

However, art history has no qualms in using this category when it considers that one production or another corresponds to its own past. So, for example, Egyptian art or cave paintings are categorized as art.

Likewise, both indigenous and peasant art appeal to the senses when they seek to represent the world in which they live. According to Escobar, certain cultural moments are thus stressed and safeguarded, resulting in tense configurations equivalent to what the West understands as art.

PARTICULAR NOTES

Both indigenous and popular art have particular characteristics that differentiate them from modern or so-called contemporary art. These forms of art, unlike modern art works, have not needed to appeal to autonomy to separate themselves from a belief system. They have guarded a narrow relationship with it and at times the forms are intimately connected to ritual. The poetry that surrounds an object is mixed up with both beliefs and everyday life in such a way that they cannot be separated out. In this sense, the postulation of an indigenous or popular art form questions the notion that for art to be art, it must be devoid of function.

The notion of originality is also called into question, since these cultures work for the most part along the lines of traditions from the past, and their ways of resignifying and reelaborating these forms propose other paths than those taken by erudite art. The question of who authored a work is not a primary one, although with the passage of time this is changing, and many ceramic makers and wood carvers are signing their works.

Popular or indigenous art strengthens its forms and creates dense meanings that correspond to the conditions of existence and production of the community in which they are created; indeed, this perspective of thinking about art shakes up the established conventions of what centers of learning have defined as “contemporary art.”

A detail from the painting “La Próxima Cena” (The Next Supper), a xilopainting by Carlos Colombino. Photo courtesy of Lia Colombino, Museo del Barro.

THE MARGINS

The Museo del Barro, with every action it has undertaken—often outside the scope of what is considered usual for a museum—has tried to make more malleable the borders of certain academic categories. Following this model, it finds other ways of involving itself in the world.

The postulation of indigenous and popular art comes from this ability to make the borders between different types of art more flexible. It looks to shake up the certainty of fields of knowledge; to move apparently fixed concepts so that we can observe that reality moves, letting one see what is out of sight. It appears.

Indigenous and popular artists, from their ways of responding to their reality, attack the gaping wound that the Western conception of the history of art has left open. The work of Ticio Escobar and the effort that the Museo del Barro has demonstrated from the beginning bear witness to these processes and contribute to the continual shaking up of the borders that have been, perhaps for way too long, unmovable

Movilizar los márgenes

El arte popular e indígena desde la perspectiva del Museo del Barro

Por Lia Colombino

El exterior moderno del Museo del Barro. Foto cortesía de Lia Colombino, Museo del Barro.

Entrar en el Museo del Barro en Asunción es sumergirse en un cúmulo de imágenes que el recorrido va entregando al paseante, no del todo ordenadas, no del todo categorizadas ni clasificadas con el sentido que suelen hacer este tipo de instituciones.

El Museo del Barro, siguiendo esa línea, guarda para sí la ambigüedad de ser un museo sin que esa palabra le vaya bien del todo. Trata de movilizar el margen mismo que delimita el concepto que se le otorga a la palabra, para desacomodar y hacerla permeable.

Se trata de un museo de arte, palabra cuya definición también ha sido movilizada y ha tratado de incluir, al decir de Ticio Escobar, “la belleza de los otros”.

INTRODUCCIÓN A UNA BREVE HISTORIA: EL MUSEO DEL BARRO O LA MANIFESTACIÓN DE LA DIFERENCIA

El Centro de Artes Visuales/Museo del Barro ha sido constituido a través de diversos emprendimientos a lo largo de más de cuarenta años de trabajo. Su particularidad: es un museo que ha sido gestionado por artistas, antropólogos y críticos de arte. En primera instancia fue creado como un proyecto que les permitiera el desarrollo de sus prácticas al margen del Estado, y en oposición a sus políticas.

Los tres museos que conforman el Centro nacieron separadamente y las circunstancias posteriores hicieron que se unieran en un solo edificio y que fueran un solo proyecto. Sus antecedentes se remontan a la Colección Circulante fundada por Olga Blinder y Carlos Colombino en el año 1972. Dicha colección, sobre todo de gráfica de raíz erudita, no contaba con un espacio propio e itineraba.

En 1980, mientras se empezaba a construir un espacio propio, se inaugura el Museo del Barro en una pequeña casa. En este proyecto trabajarán Osvaldo Salerno e Ysanne Gayet, además de Carlos Colombino. A este grupo se integrará luego Ticio Escobar.

El interés por el arte popular e indígena se había instalado en este grupo mucho antes, de la mano de Josefina Plá y tantos otros referentes como Livio Abramo, Bartomeu Melià y la misma Olga Blinder.

En 1984 se inaugura la primera sala de lo que más tarde será un complejo que albergará tanto las colecciones de Arte Popular (Museo del Barro) y las del Arte de las Etnias (Museo de Arte Indígena) como diversas expresiones del Arte Urbano del Paraguay e Iberoamérica (Museo Paraguayo de Arte Contemporáneo).

El tratamiento de las obras en el museo se realiza de tal manera que el arte popular y el indígena se ubican en pie de igualdad con respecto al arte urbano o “erudito”. El museo pretende que estas obras se confronten y dialoguen en un ámbito de respeto de las diferencias. El proyecto pretende desmentir el mito oficial que reduce la producción simbólica popular e indígena a lo “folclórico”, “autóctono” y “vernáculo”: a “lo nuestro”. Es decir, a versiones trivializadas de dicha producción, desprovista de los pliegues y las opacidades de lo diferente.

Cuando Ticio Escobar, quien ha pensado el arte paraguayo desde ese triple lugar de manera sistemática, escribe La Belleza de los Otros (1994), cuenta el relato fundacional que sustenta el libro: El brazalete de Túkule. Túkule, un gran chamán ishir, está haciendo delicadamente un brazalete llamado oikakar (en el soporte de una red realizada con una fibra vegetal hecha de una bromeliácea se atan, una a una, pequeñas plumas y plumones). Ante la pregunta de Ticio, de por qué le agrega una línea de plumas de distinto color a lo que ya parecía terminado, le contesta: “Para que sea más bello”. Ese brazalete que confunde sus funciones, que es ceremonial, chamánico y ritual, a la vez debe brillar, debe dirigirnos la mirada.

La idea del museo y de su recorrido, pretenden borronear las fronteras que separan los distintos lugares de enunciación del arte, como están borroneadas las fronteras entre lo popular, indígena y urbano en el Paraguay mismo. Así, el museo posee tres entradas desde un patio central. A partir de allí, el visitante puede perderse y en una especie de juego circular, siempre volver al mismo sitio. El Museo del Barro no tiene un solo recorrido, tampoco se lee de izquierda a derecha ni se empieza como los estudios de público lo requieren, tratan de dejar eso al azar o más bien tratan de no exigir un orden previo. El museo deja abierta la posibilidad del visitante a tener una experiencia, que algo acontezca.

Portador del lenguaje de la diferencia, intuitivamente al comienzo–primero llegó la práctica y luego la teoría- y más tarde asumiéndose así, el Museo del Barro transitó un camino que fue develándose a la medida del paso. Fue conformándose fragmentariamente desde la contingencia total, hasta que cuaja (nunca cuaja del todo), en un lugar (en dos: el lugar físico y el lugar de la palabra).

El arte paraguayo, en ese transitar distintos lugares de enunciación, quiso tener, en el Museo del Barro, un espacio en el cual pudiéramos mirarnos desde múltiples rostros, interpelarnos en ese nosotros que en Paraguay son dos (por lo menos dos, la lengua nos pone siempre en evidencia). En guaraní, el idioma de la mayor parte de la población paraguaya, posee dos “nosotros”: uno incluyente (ñande) y otro excluyente (ore). Estos dos nosotros configuran otra forma de entender la(s) identidad(es). Si bien desde la cultura oficial se intenta por diversos medios de unificar un “ser nacional”, la misma lengua lo desmiente en todo momento.

LA ESCRITURA DEL HACER

La idea de hacer dialogar y hacer converger las producciones artísticas de los diferentes pueblos del Paraguay se gestaba desde una práctica que no planificó en tablero sus acciones. Mientras, Ticio Escobar se disponía a escribir Una interpretación de las artes visuales en el Paraguay (publicada en dos tomos, el primero en 1982 y el segundo en 1984) y se encontraba con el dilema de dar palabra a la diferencia, y un lugar en una historia que le negaba.

Será con El mito del arte y el mito del pueblo que Escobar consolida un pensamiento que equipara lo popular e indígena y, de esta manera, asienta una equivalencia. Fue una intervención que sentó las bases de una discusión más acabada sobre esas modernidades otras y también sobre lo erudito y lo popular, no enfrentados en una disyunción binaria, sino planteados como términos de una cuestión que problematiza y define relaciones. Este texto reúne, en registro escritural, la vocación del CAV/Museo del Barro. Se sale de la teoría del arte para adentrarse en la teoría de lo cultural y sus implicancias políticas: las disputas por el control hegemónico del capital simbólico de un territorio devenido nación.

Este texto, al interior del proyecto que le dio cobijo: el Museo del Barro, significó la atadura de la praxis, el fundamento teórico que amarrara cuestiones que iban paralelas al hacer.

Ese concepto de arte que maneja Escobar y por extensión, el Museo –esa manipulación de formas sensibles que perturba la producción de sentido– permite plantear la inserción del concepto de arte popular en la escritura de otra historia del arte y empezar por dislocar conceptos eurocéntricos. Tales conceptos tienen que ver con la autonomía del arte, el concepto de contemporaneidad, el de unicidad, por nombrar algunos.

EL ARTE PARA LAS COMUNIDADES INDÍGENAS Y CAMPESINAS

Una de las mayores discusiones con respecto a la utilización de la palabra “arte” para nombrar las producciones estético-poéticas de culturas no-occidentales tiene que ver con un hecho concreto. Estas culturas no utilizan esa palabra para nombrar la producción de formas sensibles. Estas comunidades, en su gran mayoría, no han considerado sus producciones como obras de arte.

La Historia del Arte, sin embargo, no ha tenido prurito alguno para utilizar esa categoría cuando considera que tal o cual producción de sentido corresponden a un pasado propio. Es así con el arte egipcio o el rupestre.

No obstante, tanto la cultura campesina como la indígena apelan a la sensibilidad cuando buscan representar el mundo en el cual viven. Según Escobar, ciertos momentos culturales son puntuados, apuntalados y sus resultantes son configuraciones crispadas, equivalentes a lo que Occidente entiende como arte.

LAS NOTAS PARTICULARES

Tanto el arte indígena como el popular, posee unas notas particulares que lo diferencian de las notas que el arte moderno o el llamado arte contemporáneo consignan en relación a sus prácticas.

El arte popular o indígena no ha necesitado apelar a una autonomía que lo separe del culto. Ha guardado estrecha relación con el mismo y a veces hasta ese momento de crispación de la forma está íntimamente ligado a la eficacia de un rito. La poesía que guarda un objeto se entremezcla tanto en el culto como en la vida cotidiana de tal manera que no pueden separarse. Es en este sentido que la postulación de un arte indígena o popular discute esa noción de que el arte, para serlo, debe estar desprovisto de función.

También discute la noción de originalidad, ya que estas culturas trabajan, la mayoría de las veces, a partir de la pervivencia de una tradición cuyos tiempos son otros y sus maneras de re-significar y re-elaborar sus formas proponen otros caminos que aquellos tomados por el arte erudito. Asimismo no hay una primacía de autoría, aunque con el correr del tiempo eso va cambiando y muchas ceramistas o tallistas están firmando sus piezas.

Si bien estas notas particulares, lo separan de aquel concepto de arte heredado de Occidente, el arte popular o indígena afianza sus formas y trabaja significaciones densas que responden a las condiciones de existencia y de producción de la comunidad en donde se desarrolla; es por ello que la existencia de estas otras maneras de pensar el arte discute también con el concepto de contemporaneidad que suele utilizarse y hace ingresar otra contemporaneidad, acorde con cada una de estas realidades diversas.

LOS MÁRGENES

El Museo del Barro, desde cada acción que ha emprendido –muchas veces fuera del ámbito de lo que se entiende, generalmente, por una institución museística- ha intentado movilizar los márgenes que resguardan con celo ciertas categorías académicas. El mismo modelo de museo encuentra en este proyecto otras maneras de implicarse con la escena en la que se desarrolla.

Es por eso que la importancia de la postulación de un arte indígena y popular viene de la mano de esta movilización de márgenes. Busca la inserción de un pequeño temblor dentro de la certeza de los campos del saber para movilizar lugares aparentemente fijos con el fin de que el marco, ese a través del cual observamos la realidad, se mueva, deje ver aquello que se encontraba fuera de la visión. Aparezca.

Los artistas indígenas y populares, desde sus otras maneras de dar respuestas a la realidad que les es propia, atacan la herida que deja abierta la concepción occidental de la historia del arte. La lectura que ha hecho Ticio Escobar y que ha tenido en el Museo del Barro su lugar de inscripción, evidencia estos otros procesos y contribuyen a que sigamos movilizando esos márgenes, quizá hace demasiado tiempo, quietos.

Spring 2015, Volume XIV, Number 3

Lia Colombino is the director of the Museum of Indigenous Art that is part of the CAV/Museo del Barro. She teaches at the Instituto Superior de Arte de la Universidad Nacional de Asunción and coordinates the seminar Espacio/Crítica. She is part of the Conceptualismos del Sur network.

Lia Colombino es directora del Museo de Arte Indígena perteneciente al CAV/Museo del Barro. Docente del Instituto Superior de Arte de la Universidad Nacional de Asunción. Coordina el Seminario Espacio/Crítica. Foma parte de la Red Conceptualismos del Sur.

Related Articles

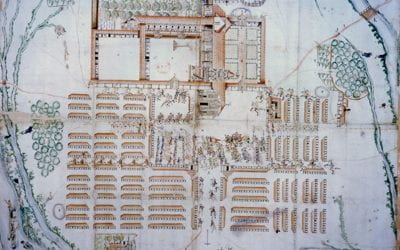

Jesuit Reflections on their Overseas Missions

When you think of Jesuits in their missions around the world, you—the casual reader—might not think of Plato or ancient Greek authors. Yet two of these…

Paraguay: Un país en una lengua misteriosa y singular

English + Español

If you arrived in a country where almost 90% of the inhabitants speak Guarani, an official and national language along with Spanish but do not identify themselves as “Indian” or aboriginal…

Territory Guarani: Editor’s Letter

DRCLAS receptions are bustling affairs, sparkling with ample liquor, Latin American tidbits and compelling conversations. It was at one of these receptions that Jorge Silvetti and Graciela Silvestri first approached me casually regarding an issue about the Guarani…