Beyond Language Lays Monstrosity

Roque/Raquel Salas Rivera on Queer Being

“[W]hat is the difference between cuir and queer? the difference is the difference between knowing and not knowing IVÁN.” Angry and grieving in the wake of the unsolved murder of Iván Trinidad Cotto, a gay Puerto Rican student at the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez, renowned Puerto Rican poet Roque/Raquel Salas Rivera penned these words. I first learned of Iván when I read “Huequitos/Holies” by Salas Rivera for a class taught by Tommy Conners, a professor of Latinx and queer studies. Struggling to comprehend the words above, I now return to the article with a different perspective: what if we are not supposed to understand these differences? For most people like me, the life of Iván will only be known through his death, a spectral reminder of the precarity of queer life in Puerto Rico. Our inability to know Iván beyond his death is reflective of the incomprehensibility of “cuir” in the Spanish language—that is, there is an unknowability to people that language cannot capture. When this colonial language refuses to accommodate queer being into its social script, we notice how queer bodies take up space differently or are violently removed. For Salas Rivera, living in the wake of his dear friend Iván animates poetic dialogues about the limitations of language.

Turning to the aesthetic helps us see where words fall short of capturing our complex being. The intersectional nature of Salas Rivera’s work—thinking along vectors of politics, sociolegal frameworks, and identity—invites encounters and weavings between realms of queerness and political theorization and Latinidad. Using Salas Rivera’s work as a lens, I reveal how queerness comes to the surface through alterity when the gendered architecture of a language fails its users. I will show how Salas Rivera’s literary practices articulate a critique of language through strategies of refusal and monstrosity. His poetics emphasizes how the indeterminacy in which Puerto Rico and its inhabitants are situated underpins conversations of language. He then exposes language as an inadequate technology of empire by refusing to operate within its registers of gendered and legal doctrine that have systematically enacted a violent capture onto queer Puerto Ricans. He poetically explores how the ubiquitously used Spanish language—a remnant of the Spanish Empire—has silenced queerness. This interrogation of language, fusing the personal and the political, reveals how Salas Rivera harnesses aesthetics as a critical instrument through which to deconstruct colonial power and reinsert cuir voices and bodies into broader literary and political conversations.

To do this, I start with the body—his body—which is foregrounded in his work, creating space for differently embodied subjectivity. Salas Rivera is an ambiguous subject of the state and subject to the structural constraints of the Spanish language, which does not capture his gender fluidity. As an inhabitant of Puerto Rico, an unincorporated territory, he is legally subject to the plenary power of the United States Congress.

The irony of this political cartoon—Uncle Sam, a personification of the federal government, sweeping the lives and stories of Puerto Ricans under the “rug” (Puerto Rico’s flag)—speaks to the afterlives of imperialism evident in the colonial relationship between the United States and Puerto Rico. Cartoon by Andy Marlette.

Though held captive by different forms of language—Spanish and the law—Salas Rivera and Puerto Rico embody similarly monstrous positions that emerge in the absence of description (the monster under the bed image is first introduced in while they sleep (under the bed is another country) 2019). As Latin American and queer studies scholar Joseph Pierce muses, “[M]onsters reflect cultural anxieties and serve to define the normal and the deviant…monsters are symptomatic of the way a culture sees itself, its history, its future, and, often, its end.” Puerto Rico evokes colonial anxieties about the “end” of American democracy by way of a theoretically impending revolt. Meanwhile, cuir Puerto Ricans materially exemplify the effects of imperial subordination. Their Caribbean subjectivity is symbolically antithetical to Western cultural norms, coupled by a queerness that defies Anglicized gender and sexuality binaries. The law becomes a mechanism for control, queering Puerto Rico as politically unknown. By legally forcing the island and its inhabitants into the closet, bound shut from the statehood and sovereignty, the law becomes a preventative measure against the possibility of Puerto Rico’s unruly monstrosity.

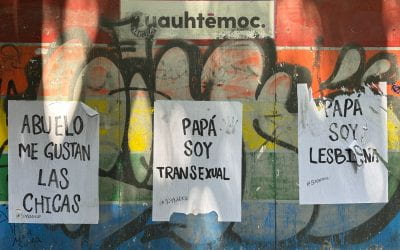

In his 2020 collection X/Ex/Exis: para la nación, Salas Rivera resists the capture of normative language by engaging in a moving away from and a moving toward. To be cuir is to engage in a kind of double dissidence—it is a disfiguration of the English language and a neologism that counters queer nonexistence in the Spanish language. While it is phonetically similar to its Anglicized derivation, “queer,” this latinized variation redirects our focus toward the Caribbean and Latin America, destabilizing normative geopolitical locations of queerness and inviting us to read and see the cuir in Puerto Rican poetics.

In X/Ex/Exis, where each poem is translated in English and Spanish, we read movement across Salas Rivera’s translational choices, in the gaps and ambiguities of pronoun usage and temporality. By naming the shortcomings of language, Salas Rivera creates a cuir heuristic—a method—for acknowledging and resisting political and semantic capture: the monster. Salas Rivera’s narration of impossibility reveals that monstrosity as an un/dead figure comes in by necessity due to the insufficiencies of language. Salas Rivera is not attempting to locate or create a new lexicon that might more accurately describe “cuir.” Rather than trying to work within a linguistic system that renders cuir untranslatable, he pushes past language and reaches for monstrosity. In the monstrous aesthetic, Salas Rivera makes legible the colonial entanglements of language by centering cuir bodies and experiences that otherwise would not be articulated or seen.

We may read “they,” a poem from X/Ex/Exis, as a reminder of how the Spanish language upholds gender binaries that exclude and erase gender nonconforming people from the realm of legibility. More importantly, this poem shows us how cuir poets like Salas Rivera monster against normative language:

they

¿de qué comemos cuando muere un nombre?

ayer pasó tu madre pero no me reconocía

como la amiga de tu amiga, la previa.

¿ de qué se trata tener una amiga muerta

en la certera con la foto de un niño raptado?

¿has visto a mi hijo?

es bajito y colecciona fotografías de columpios.

mi pelo corto no es professional;

el tuyo largo no te prepara.

entre los dos, averiguamos cómo fingir

que somos merionetas y no personas.

es difícil llevar la cuenta de los días

desde la última vez que salimos.

¿de qué se trata salir a la calle

y tener que explicar que

no solo no eres aquella

tampoco eres aquello?

en este, nuestro idioma,*

no existe un plural que no me niegue.

* (nuestro idioma es el español. nuestro, pero no exactamente el mío.)

As the gender-neutral title ironically indicates, the inflexibility of this colonial grammar accounts for the untranslatability of cuir—that which cannot be named or understood leaves room for fear, misunderstanding, and violence (as was the case for Iván and many others). Salas Rivera’s poetics perform a strategic monstering that defends cuir existence by embracing alterity. Monstrosity allows us to rethink land and bodies outside of a human/nonhuman divide and reconsider what else can be encompassed in monstering. The poem reframes monsters not as incomplete or disfigured but instead as expansively human. The monster is personhood seen through a lens other than colonial paradigms of humanity. It has the capacity for holding and expressing excess and the unknown in ways that cannot be understood through frameworks of whiteness, biological sex, and heterosexuality. The monstrous cuir invites you to see more than the violence committed against them and also imagine how queerness in Puerto Rico encompasses joy, love, pleasure, death, loss and hope.

Etymological roadmap of the word “monster,” originally derived from the Proto-Indo-European language family. Image by Online Etymology Dictionary.

Monstrosity first comes into play in the rhetorical opener to “they,” when Salas Rivera asks, “[W]hat do we eat when a name dies?” The seemingly nonsensical question invokes mourning rituals, such as when families receive baked goods and meals while they grieve a lost loved one. Food operates in a paradoxical manner here: it reminds us of death even as it sustains other living beings. How do we make sense of the death of a name? Can a person live on even when their name does not? In “they,” it appears that the zombie-like figure—the ostensibly “amiga muerta”—hovers over a temporal threshold of pre- and post-gender transition. The act of transitioning, then, is a cycle of death and life that occurs within the self: the subject “no eres aquella” but is not quite dead. They are dead in the sense that the prototypical name assigned to them at birth is rejected and cast aside. The subject is then reborn as a more authentic version of themselves. Here we arrive at a post-transition undead cuir being.

Salas Rivera’s self-reflexive poetics, which foreground his own transition, lay bare the violence of illegibility that colonial language inscribes onto cuir people. Centering his own personal experience, we see how transness, which cannot be adequately named in the Spanish language, becomes a source of interrogation and confusion: “[Y]esterday your mother stopped by, but she didn’t recognize me as your friend’s friend, the previous one.” This misrecognition occurs at the intersection of two gendered temporalities—the before and the after. The monstrosity of the cuir is situated at the interstice of unknowing: when you cannot articulate your being, it becomes difficult for others to understand you. He laments that “[I]n this, our language, there exists no plural that doesn’t deny me.” The monster is what emerges when Spanish denies Salas Rivera the grammatical tools to express his gender nonconformity.

Using figural knots to register the entanglements of colonial grammar, Caribbean and queer studies scholar Christina León writes that there is no language that has gender transmitted faithfully. Both Spanish and English are entangled and complicit in this violent denial. Spanish offers two paths of identification: one must fall into either the ella/ellas or él/ellos category. Yet both singular and plural variations of Spanish pronouns silence the cuir subject. There exists no word for gender neutrality within the latinized lexicon of identity; while “elle,” a proposed alternative, may capture gender fluidity in its shift away from the “a” and the “o,” it is not officially recognized or widely utilized within the Spanish language, especially outside of the United States. Thus, te Spanish language effectively uninscribes Salas Rivera and others from its register—the insufficiencies of “nuestro idioma” become a linguistic rejection of cuir being.

The Anglicized variation of queerness used in the United States, where neutral they/them pronouns have been adopted by many and recognized by official word repositories, such as the Merriam-Webster Dictionary, is not without its own colonial entanglements. For Puerto Ricans, English is simply a transfiguration of colonial registers, a reminder of the imperial dynamic at play between the United States Empire and its Caribbean colony. Caught in the crosshairs of a gendered negotiation between two colonial languages, Salas Rivera cannot escape the hegemonic regimes of gender wrought by Spanish colonialism nor the ongoing state of capture under the United States.

In the absence of a comprehendible explanation of the cuir, which cannot exist in the Spanish language, the figural un/dead monster embraces the pre-transition “aquella” and the post-transition “aquello” (translated in English as “thing”). Transiting space as both the dead and undead, the monster capacitates a mode of being that is beyond the scope of recognizable humanity, making way for what cannot be captured in “queer” or in the limited parameters of Spanish or in the legal binds that constrain Puerto Rico. Monstrosity as a method—that is, something you look for—moves beyond the locus of empire to see the colonies. When you look in the closets and under the beds, you will find the monstrous beings that exceed normativity and its cages constructed from language.

Nina Alexa Peralta McCormack is a senior at Harvard studying History & Literature with a focus in Latin America. Their scholarly work lays at the intersection of Latinx, indigenous, and queer studies, centering around critical race and performance theory, aesthetic production, and daily praxis in the Caribbean and Latin America. Questions of sovereignty, nationhood, language/translation, and how bodies take up space motivate their studies and academic projects.

Related Articles

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.