Boats of Hope

VASI’s Community-Led Health Care

The first river ambulance in the district of Sarayacu, Peru with Omer Miguel Reategui Panduro, the boat driver, waving from the front.

In May 2020, almost a year ago, as Covid-19 spread across the Amazon, it took nurse obstetrician Elizabeth Martel Fernández about 14 hours to reach the hospital from the community of Juancito in the district of Sarayacu in the Peruvian Amazon. She was experiencing severe symptoms of the virus and needed oxygen, unavailable at that time in her rural health center, where she is the director. Her colleagues transported her in an old aluminum boat powered by a 40 HP motor. They lay her in the bottom and covered the boat’s sides with plastic tarps to protect her from the wind, rain and equatorial sun.

At that point in the pandemic, VASI (Amazonian Vision for an Integrated Sustainability), a community-founded, led and designed non-governmental organization (NGO) had just begun its work on health care and Covid-19. Now a year later, we are leading a campaign to outfit boats as ambulances to serve the district, facilitating an international working group to increase access to quality local health care, including addressing the continued waves of Covid-19, and working to create long-term sustainable community health projects.

It has been an intense year, a year that has quite frequently brought us to our knees, and a year that is underlining the importance of creating a resilient collaborative way of work.

VASI was formed in 2016 by representatives from nine communities from the district of Sarayacu, Loreto, Peru, students from those communities and a small group of scientists. The communities had determined that they could no longer wait for the government or some other outside group to address local urgent needs. They wanted to make their voices heard regarding pressing conversations around biodiversity, conservation, climate change, quality of life, education, health and the Amazon. They wanted to create an organization that could not only help their communities create sustainable futures, but that would also help other rural and marginalized communities anywhere on our shared planet, develop and bring to fruition locally led solutions. Currently, VASI’s three main programs are increasing access to quality education and health care, creating sustainable livelihoods and food sovereignty and community-based collaborative research.

While we didn’t predict a near-future pandemic, VASI’s investment in building a strong, flexible, community-led organization and an international network has allowed us to respond quickly and effectively to the situation. The people of the district of Sarayacu, and throughout Peru, have a deeply collaborative tradition. Mingas, and other communal workdays in which every able-bodied citizen works together without pay (and often in difficult situations) to accomplish a communal good, are the norm. This collaborative spirit is one that VASI aims to embody and infuse in all of its initiatives. VASI has created a coalition of collaborators to work on their projects, both locally, in the communities and Peru, as well as internationally.

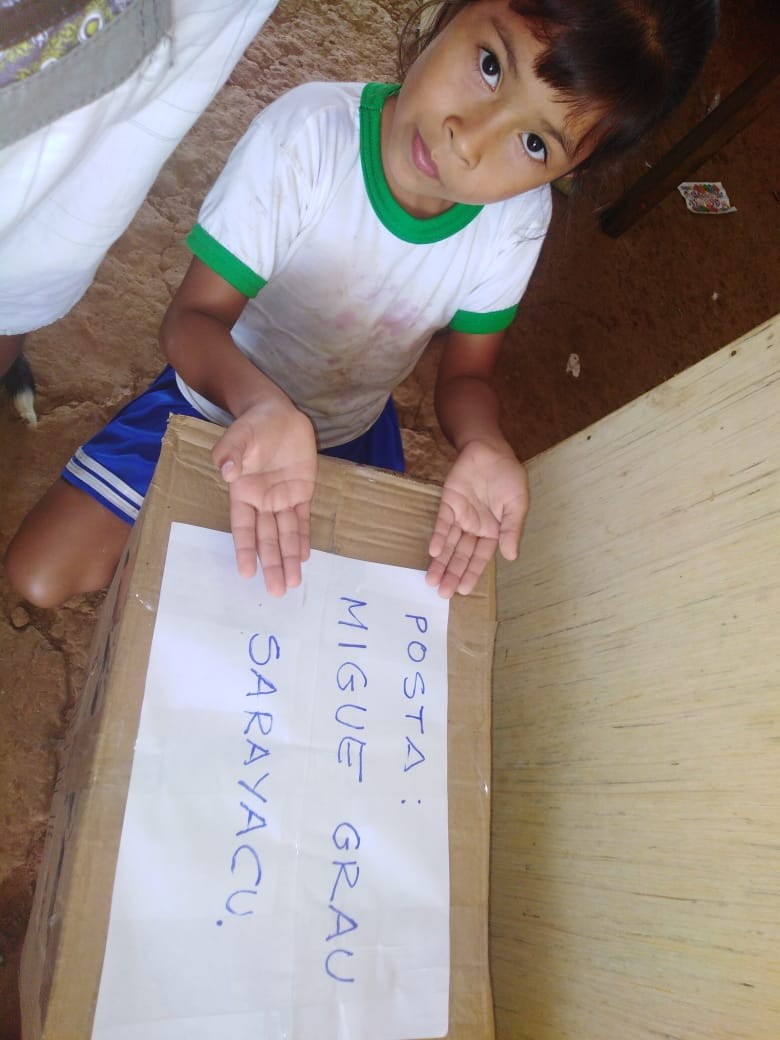

Alana Hoyos García, the eight-year-old daughter of the president of VASI’s local board of directors, stuck in Pucallpa at the beginning of the pandemic, helped to pack handwashing and disinfecting supplies for the district’s health posts.

When the pandemic hit, we spent hours and hours on the phone, talking to local health professionals, residents and authorities, trying to help work out plans. We also stayed in contact with a group of community residents, young people who had been living in Lima for work. When Peru’s strict quarantine went into effect, they no longer had work and couldn’t pay their rents. With no transportation available, they walked about 466 miles from Lima to Pucallpa. They started at sea level. Following the “Central Highway,” they crossed the Andes and one of the world’s highest passes at 15,807 ft. before descending to Pucallpa. Once in Pucallpa, they planned to get in boats (with official permission or not) and make their way two to three days down river to their hometowns. They knew that at the very minimum, once home, they could at least fish and eat. While mostly, we were talking to these young people out of concern, trying to help keep communication with them during their difficult journey, VASI also worked with local authorities to push for the development of a plan for when they arrived and hence help ensure they wouldn’t become accidental vectors of the virus.

Our first actions to address the pandemic were to provide a month’s worth of P.P.E., sanitation supplies and basic medicines, to fill the gaps as the government put in place larger- scale plans.

“VASI acted at just the right time…those were the first blocks or packages [of P.P.E] that arrived. Nationwide the country was almost entirely out of them” Larry Manuyama Sharihua, a nurse obstetrician in Juancito.

However, P.P.E. and basic medicines didn’t erase the most basic realities of the district: there is no clean warm water with which to wash hands; four out of every five communities have no health care professionals; more than half have no access to any form of telecommunications, and only a handful have internet access. There are no roads, there are no hospitals, and there were no ambulances. Occasionally a float plane is able to land and carry a person to the nearest hospital, but otherwise, a person—even a highly contagious person must travel on crowded commercial cargo ferries or smaller even more densely packed rápidos, long tin boats that cram up to 150 people inside of them.

In May 2020, the old aluminum boat that carried Martel Fernández would have woven through the water of the Ucayali River, the Amazon River’s main headwater, avoiding partially submerged trees and flotsam. On either side of the river, the Amazon rainforest would have reached towards the sky, interspersed with lower initial growth, fields and small towns. As they headed upriver, the foothills of the Andes would have begun to rise. At first, they would have looked like low clouds, but within hours these same foothills would roll down to greet the river’s edge. In front of one broad beach that forms annually just upriver of a large town, a pod of pink river dolphins (Inia geoffrensis) is almost always hunting and playing, breaching the water and crossing underneath the boat. At times, the beauty would have been so striking and intense, it would have been jaw dropping.

But Martel Fernández probably didn’t see any of this, she was struggling just to stay alive.

“[At the hospital] there were a lot of patients with Covid, they even died in front of me, but I tried to think that at home … that my husband and son were waiting for me,” she recounted. “I would distract myself by helping the people by my side.”

Martel Fernández said that it took her 30 days to recover and return to doing the work that she loves, caring for people and delivering babies, as well as playing a central role in VASI’s Health Working Group.

Raúl Inuma Ojanama, a member of VASI’s local board of directors, in the town of Nuevo Dos de Mayo getting tested for Covid-19by Dr. Óscar Manuel Zamora Huancas, who walked through mud on a rainy Sunday in March of 2021 to reach the community.

Covid-19 in VASI’s Founding Communities

Martel Fernández’s experience with the virus is not unique and underlines that masks and medicines alone won’t even begin to solve the broader health care issues in these communities.

For many months, Peru had the highest per population death rates from Covid-19. And even before the pandemic hit Peru, it was already the worst year on record in terms of dengue fever. Martel Fernández and colleagues estimate that somewhere between 80-95% of the district’s residents—and almost all of the health care professionals—contracted the Covid-19 virus in the first wave. Now the communities are reporting a steady stream of second and potentially third re-infections, many of which have been confirmed (via rapid tests). We know that at least two variants B.1.1.7 (poorly referred to as the “British” variant) and P.1. (poorly referred to as the “Brazilian” variant) have been identified in Iquitos, the region’s capital. Given the constant movement of people along the river—from Iquitos, to the communities, to further upriver to Pucallpa—it is likely that these variants are present in the communities. But given their rural nature, the lack of even one hospital, no one has been able to conduct the genetic analyses. Peru has begun a limited vaccine campaign, and approximately two out of every three of the district’s health professionals are now vaccinated. At this point, it will be months or longer before vaccines are available to the bulk of communities’ residents. Meanwhile, dengue, malaria and other zoonotic diseases have also continued to increase, and with the recent high floodwaters, water-borne illnesses have become widespread.

Ongoing Health Care Issues

Compounding the crisis caused by the pandemic are issues of access to healthcare. The district of Sarayacu—with about 70 towns and a population of 17,000—is roughly the size of the state of Delaware in the United States. Fourteen (soon to be 15) of the larger towns host health posts or centers, but these have no EKG’s, no ventilators, no imaging equipment, no major equipment, no capacity for surgeries, no ICU’s. People in the vast majority of towns live more than an hour (and up to 10 hours) from the nearest nurse or doctor. In fact, there are only three medical doctors in the district, and one of them spent months in Lima, Peru’s capital, on a ventilator due to Covid-19.

There have been periods of intense loss. From April through June, October through December, and March 2021, it seemed we lost a colleague, family member, friend or neighbor daily. The government took what initially seemed to be strong positive actions: putting the entire country in a complete lockdown, with military enforced curfews, and people only allowed out of their homes to buy groceries, medicines or visit the doctor. But due to the reality that the vast majority of people in the Amazonian region work day-to-day, almost no one could afford to stay in their home for more than a day. People have little access to savings, cash or food storage. As Covid-19 made a slow trek from the cities to the communities, we feared the worst.

Everyone’s phones reminded them, through constant government messages. to wear a mask, maintain six feet distance and wash their hands with abundant soap and warm clean water—but there were no masks, nor is there clean water, much less warm water, everyone shares space, and in the communities, the lack of telecommunications meant these messages weren’t arriving. By the time we were able to get masks and other P.P.E. to the health care professionals, four out of every five of them had already had the virus.

Elizabeth and a team of medical professionals from across the district in the river ambulance as they head out to visit remote communities in January 2021. During January and February, they were able to visit 23 towns and provide preventative and basic care to more than 1,300 people. The river ambulance has facilitated the first two visits to the indigenous community of Santa Rosa by medical professionals in 5 years.

River Ambulance Project

After her personal experience, and recognizing the growing need, Martel Fernández and other health professionals in the district asked VASI to spearhead a campaign to launch several #RiverAmbulances, speedboats outfitted as ambulances. The first #RiverAmbulance was launched in the community of Juancito on December 12, 2020. At this point, it has an 85 HP motor, a covered roof and sides and two stretchers. The second and third boats were launched on April 29. We are now raising funds to fully outfit these three with medical and ambulance supplies, and to launch a fourth boat. It is a collaborative effort. Businesses owned by people born in the district have been pitching in; the provincial health authority has donated the boats that they and the municipal government are paying to rehab. The provincial health authority will maintain the motors and keep the boats supplied with fuel for evacuations. VASI has bought the motors, drive accessories, and many other supplies.

Two days after the launch of the first boat, there was a driving rainstorm and in the farthest outlying community a woman lay near death with an obstructed bowel. Health care professionals left from Juancito, picked her up, and, after 14 grueling hours of navigating through the storm, delivered her to the nearest hospital where lifesaving surgery was successfully performed.

That same day, a teenager lay prostrate and near death from a hunting accident in another town. Because the boat was already too far away evacuating the first patient, the young man waited 36 hours to be evacuated to the nearest hospital. He was then flown to a regional hospital where they were able to remove bullets from his spinal column.

VASI’s team is raising funds to ensure all four #RiverAmbulances will be fully equipped with medical supplies—able not just to evacuate people during emergencies, but also to take basic and preventative care to the approximately 55 communities with no health care professionals.

We are also continuing to build our health care coalition. Doctors, fellows and students from Harvard, Stanford, George Washington and Thomas Jefferson universities are working with the local and provincial health care professionals, all collaborating to make sure the ambulance project will be sustainable over the long term, design a rapid needs assessment and implement follow-up programs. We have recently been awarded a grant from the Tides foundation that will provide the funds to pay young professionals to join our on-the-ground team and carry out the need’s assessment.

Elizabeth and a team of medical professionals on their way to the indigenous community of Santa Rosa, December 2020. To reach the community, they first travelled down river via in the new River Ambulance, then took this smaller boat up a small stream, and then walked the remaining portion of the journey.

We are actively looking for dedicated individuals, organizations and businesses who want to get involved providing in-kind, logistical, financial and/or consulting support. The one thing we ask of all of our partners (in addition adhering to the principles of equality and transparency) is part of what separates us from most organizations: to immerse themselves with us in this particularly rich tradition of collaboration one in which community members are respected as leaders and experts working hand in hand with everyone else.

Wicberto Pinedo García, member of VASI’s Health Working Group and a nurse obstetrician for the provincial hospital in Contamana, has held several roles in the health administration and helps lead the collaboration with VASI. In December, he highlighted the effects of Peru’s political instability (including three national presidents during one week in Nov) and the need for locally based health programs. “Our population (nationally) is very diverse, both geographically and culturally. Yet, public policy is applied by national standards. If policy was applied based on local realities, it would be better. It isn’t the same to have a health post on the coast where there are highways and other services as having a health post in the Amazon without any roads.” Pinedo García was born and raised in Nuevo Dos de Mayo, one of VASI’s founding communities.

Larry Manuyama Sharihua, a nurse obstetrician, walking the last part of the trek to the indigenous community of Santa Rosa in December 2020 carrying soap, alcohol, gel and oximeters.

Devastation and Loss—Resiliency Together

The story of Covid-19 in the Amazon, as in the rest of the world, has been one of devastation and loss. It is also a story of resilience and community, with everyone from doctors, to nurses, to health care promoters who work for little or no pay, to community members and individuals and institutions from across continents doing their part.

VASI’s mission is to support rural and marginalized communities as they empower themselves and create sustainable futures. We see that human and ecosystem health and well-being are highly interdependent, and we believe that work that recognizes this has the opportunity to have an outsized impact.

As our local board of directors constantly reminds us, they don’t walk all day without pay to come to a meeting just to help their own communities. They recognize the pivotal role their communities, and the Amazon in general, play in climate change mitigation and biodiversity protection. They aim to create a model of community-led work that can be expanded to communities anywhere in the world. And that is the only way we are going to combat the challenges of our time: Together.

The 28th of January in the community of Curarina, Dr. Karla C. Robles Baradoza in a campaign to bring preventative and basic medical care to remote communities.

We recognize that ReVista generally only accepts first person individually authored pieces in Eyes on Covid-19. We honor that tradition and the power of those stories. That said, this story was truly written by all three authors.

To donate to VASI’s #RiverAmbulance campaign, you can click here: https://bit.ly/HelpFundRiverAmbulances. If you would like to get directly involved or have questions, please reach out to Nancy Dammann, at nancy@proyectovasi.org.

Botes de la Esperanza

Los Proyectos de VASI de La Atención Médica Liderada por las Comunidades

Por Samantha Neville, Edgardo Gómez Pisco y Nancy M. Dammann

La primera ambulancia del río en el distrito de Sarayacu, Perú. Omer Miguel Reategui Panduro, el conductor del bote, saludando.

En mayo de 2020, hace casi un año, cuando el Covid-19 se extendió por la Amazonía, la enfermera obstetra Elizabeth Martel Fernández tardó unas 14 horas en llegar al hospital. Salió de su comunidad de Juancito en el distrito de Sarayacu en la Amazonía Peruana hacia el hospital más cercano, lo de la cuidad de Contamana. Ella estaba experimentando síntomas severos del virus y necesitaba oxígeno, algo que no estaba disponible en el centro de salud que dirige. Sus compañeros la transportaron en un viejo bote de aluminio propulsado por un motor fuera de borda de 40 HP. Para protegerla del viento, la lluvia y del sol ecuatorial, la colocaron en el fondo del bote y cubrieron los costados con lonas de plástico.

En este punto de la pandemia, VASI (Visión Amazónica para la Sostenibilidad Integral), una organización no gubernamental (ONG) fundada, liderada y diseñada por las comunidades, apenas estaba iniciando su trabajo sobre el cuidado de salud y el Covid-19. Ahora, un año después, nosotros en VASI estamos liderando una campaña a equipar botes que sirvan como #hidroambulancias, facilitando con una colaboración internacional para así aumentar el acceso a una mejor atención médica local, lo cual incluye controlar las olas de Covid-19, y así crear proyectos a largo plazo de salud comunitaria.

Ha sido un año intenso, un periodo que frecuentemente nos han puesto de rodillas, y que está demostrando la importancia del tener un trabajo colaborativo.

VASI fue formado en 2016 por representantes de nueve comunidades del distrito de Sarayacu, Loreto, Perú, así como los estudiantes de estas comunidades y un pequeño grupo de científicos. Las comunidades determinaron que, ya no podían esperar a que el gobierno o algún otro grupo externo solucionaran sus necesidades prioritarias. Querían que sus voces fueran escuchadas en conferencias sobre biodiversidad, conservación, cambio climático, calidad de vida, educación, salud y la Amazonía. Deseaban crear una organización que no solo pudiera ayudar a sus comunidades creando futuros sostenibles, sino que también ayudara a otras comunidades rurales y marginadas en cualquier parte del planeta, desarrollando y realizando soluciones dirigidas y diseñadas de forma local.

Actualmente, los tres principales programas de VASI son: i.) aumentar el acceso a la educación y a la atención médica de calidad, ii.) crear proyectos de comidas sostenibles y de soberanía alimentaria, y iii.) ejecutar investigaciones colaborativas basadas en las comunidades.

La dedicación de VASI de construir una organización fuerte, flexible y dirigida por las comunidades juntos a una red internacional, nos ayudo a responder a la pandemia. La gente del distrito de Sarayacu, y la mayoría de los ciudadanos del Perú, son profundamente colaboradores. Mingas así como otras formas de trabajo comunal (a menudo en situaciones complejas) en que los ciudadanos trabajan juntos sin una recompensa para lograr un bien común, son lo normal. Es este espíritu colaborativo que fomenta todas sus iniciativas de VASI.

Cuando llegó la pandemia, pasemos horas y horas al teléfono hablando con moradores, y autoridades y profesionales locales de salud, tratando así de ayudar a elaborar un plan de como enfrentar la pandemia. A su vez, estábamos en constante contacto con un grupo de residentes que fueron a Lima buscando oportunidad de trabajo. En el periodo en que Perú entró en una cuarentena completa, estos jóvenes sin trabajo ya no podían pagar sus rentas, y no había medios de transporte para volver a su lugar de origen. Ellos caminaban aproximadamente 750 km (~ 466 millas) desde Lima hasta la cuidad de Pucallpa, iniciando desde el nivel del mar continuaron por la “Carretera Central”, cruzando los Andes (uno de los pasos más altos del mundo a 4.818 metros [15.807 pies]) antes de descender a Pucallpa (150 msnm). Ya en Pucallpa, planeaban subirse en botes para hacer un viaje de dos a tres días por el río hasta llegar a sus pueblos de origen. Estos jóvenes comprendieron que por lo menos en sus pueblos podían pescar y tener un sustento. Preocupados por ellos, intentamos mantener una comunicación frecuente durante su largo camino, y presionamos a las autoridades locales para desarrollar un plan para su llegada, y reducir así el riesgo de transmisión accidental del virus.

Alana Hoyos García, de ocho años, la hija del presidente de la mesa directiva local de VASI, atrapada en Pucallpa al comienzo de la pandemia, ayudó a empacar insumos para lavar manos y desinfección para los puestos de salud del distrito.

Al inicio, implementamos los establecimientos de salud con suficiente E.P.P. (equipos de protección personal como mascarillas, guantes, etc), suministros de saneamiento, y medicinas básicas para un mes, todo con la intención de disminuir las brechas a medida que el gobierno implementaba planes a mayor escala.

“VASI llegaba en momento de que debería llegar… Realmente fueron los primeros bloques o paquetes [de E.P.P] que nos llegaba. Ya nos habían casi terminado a nivel de la nación.” dijo Larry Manuyama Sharihua, un enfermero obstetra que trabaja en Juancito.

Sin embargo, los lotes de E.P.P. y las medicinas básicas no borraron las realidades del distrito: no se cuenta con agua potable y tibia, para lavarse las manos; cuatro de cada cinco comunidades no tienen profesionales de la salud; más de la mitad de las comunidades no cuentan con acceso a ninguna forma de telecomunicación, y solo unos cuantos tienen acceso al internet, no hay vías de acceso, no hay hospitales, y no había ambulancias. Ocasionalmente, un hidroavión puede arribar y trasladar a una persona en caso de emergencia al hospital más cercano (Contamana). Mas frecuente, una persona, incluso una contagiada, tiene que ser evacuada en barcos comerciales o en rápidos, largos botes de aluminio más pequeños, los cuales amontonan hasta 150 personas.

En mayo del 2020, el viejo bote de aluminio que transportaba a Martel Fernández surcaba el Rio Ucayali, la cabecera mayor del Rio Amazonas, evitando árboles parcialmente sumergidos y otros obstáculos flotantes. En ambos lados del río, la selva amazónica habría estado extendiéndose hacia el cielo, intercalada con un crecimiento inicial bajo, campos, y pequeños pueblos. Mientras se dirigían, las faldas de los Andes hubieran comenzado a elevarse. Al principio, habrían parecido nubes bajas, pero en cuestión de horas estas mismas colinas bajarían rodando para saludar a la orilla del río. Frente a una amplia playa que forma anualmente río arriba de un mediano pueblo, un grupo de delfines rosados o bufeos colorados (Inia geoffrensis) casi siempre está cazando y jugando, rompiendo el agua y cruzando por debajo del bote. A veces, la belleza habia sido tan llamativa e intensa que sería asombrosa. Sin embargo, Martel Fernández probablemente no vio nada de esto; ya que estaba luchando por mantenerse viva.

“[En el hospital] habían muchos pacientes con COVID, hasta morían ahí mi delante, pero trataba yo de pensar que en casa… me esperaba mi esposo, mi hijito,” dijo Martel Fernández. “Me distraía apoyando a las personas que estaban a mi costado.”

Martel Fernández dijo que tardó 30 días en recuperarse, pero ahora está otra vez haciendo el trabajo que la apasiona: cuidando a la gente y atendiendo a partos. Además, esta jugando un papel importante con el Grupo de Trabajo de Salud de VASI.

Raúl Inuma Ojanama, miembro de la mesa directiva local de VASI, en la comunidad de Nuevo Dos de Mayo, haciendo la prueba de Covid-19 con el Dr. Óscar Manuel Zamora Huancas. Dr. Oscar caminó a través del lodo un domingo lluvioso de marzo de 2021 para llegar a la comunidad.

Covid-19 en las comunidades fundadoras de VASI

La experiencia de Martel Fernández en cuanto a la pandemia no es fuera de lo común, subrayando que las mascarillas y los medicamentos por sí solos no comenzarán a resolver los problemas más profundos de atención médica en estas comunidades. Durante muchos meses, Perú tuvo las tasas de mortalidad por población más altas por Covid-19; e antes que la pandemia azotara a Perú, este era catalogado como el peor año registrado en términos de dengue.

Sin embargo, Martel Fernández y sus colegas estiman que entre el 80 y el 95% de los residentes del distrito, y casi todos los profesionales de la salud, contrajeron el virus Covid-19 en la primera ola. Ahora las comunidades están reportando un flujo constante de segundas y posiblemente terceras reinfecciones, muchas de las cuales han sido confirmadas (mediante pruebas rápidas).

Sabemos que al menos dos variantes B.1.1.7 (mal conocida como la variante “británica”) y P.1. (mal conocida como la variante “brasileña”), han sido identificadas en Iquitos, la capital de la región. Dado el movimiento constante de personas a lo largo del río, desde Iquitos hasta Pucallpa, es probable que estas variantes estén presentes en las comunidades. Pero por su naturaleza rural, y sumado a la falta de un hospital, nadie ha podido realizar los análisis genéticos.

El Perú ha iniciado una campaña de vacunación limitada y aproximadamente dos de cada tres de los profesionales de la salud del distrito ya están vacunados. A este ritmo, pasarán meses o años antes de que las vacunas estén disponibles para la mayoría de los residentes de estas comunidades. El dengue, la malaria y otras enfermedades zoonóticas también han seguido aumentando, y con las recientes inundaciones, las enfermedades transmitidas por el agua se han generalizado.

Elizabeth y un equipo de profesionales de salud en viaje a la comunidad indígena de Santa Rosa, diciembre de 2020. Para llegar al pueblo, primero bajaron por el Rio Ucayali en el nuevo Ambulancia del Rio, de allá surcaba una quebrada en un bote pequeño, para luego caminar el ultimo trayecto.

Problemas persistentes en la atención médica

Los problemas de acceso a la atención médica agravan la crisis causada por la pandemia. El distrito de Sarayacu, con unos 70 pueblos, y una población de aproximadamente 17.000 habitantes, es casi el tamaño del estado de Delaware en los Estados Unidos. Catorce (pronto serán 15) de las comunidades más grandes albergan puestos o centros de salud, pero estos no tienen equipos para electrocardiogramas, ventiladores, equipos de imágenes, ni capacidad para cirugías, ni mucho menos una Unidad de Cuidado Intensivo – UCI. La gente en la gran mayoría de las comunidades vive a más de una hora (o hasta 10 horas) de la enfermera o médico más cercano. De hecho, solo hay tres médicos en el distrito. Uno de ellos estaba en Lima por varios meses conectado a un ventilador mecánico debido al Covid-19.

Ha habido periodos de intensa pérdida. De abril a junio, de octubre a diciembre, y marzo de 2021, parecía que perdíamos colegas, familiares, amigos o vecinos a diario. El gobierno tomaba fuertes acciones con el intento de frenar el contagio: cerraron las fronteras, empezaron con toques de queda impuestos por las fuerzas armadas, en donde las personas solo pueden salir de sus casas para comprar víveres, medicinas o visitar al médico. Pero debido a la realidad, la gran mayoría de las personas en la región amazónica trabaja día a día, por lo que casi nadie puede quedarse en casa. Las personas tienen poco acceso ha ahorros, dinero en efectivo o almacenamiento de alimentos, mientras el Covid-19 avanzaba lentamente desde las ciudades hasta las comunidades, temíamos lo peor.

Mensajes de texto les hicieron recordar a todos que debían usar un tapabocas, mantener una distancia de dos metros y constantemente lavarse las manos con abundante agua y jabón, pero no había tapabocas, ni agua limpia, y mucho menos agua caliente. En las comunidades, la falta de telecomunicaciones hizo que estos mensajes tampoco llegaran. Y cuando por fin se pudo conseguir tapabocas y otros E.P.P. para los profesionales de la salud, cuatro de cada cinco ya habían tenido el virus.

Elizabeth y un equipo de profesionales de salud del distrito en la ambulancia del río en camino para visitar comunidades remotas en enero 2021. Durante enero y febrero visitaron 23 comunidades y brindaron atención preventiva y básica a más de 1.300 personas. La ambulancia del río facilitó las dos primeras visitas a la comunidad indígena de Santa Rosa por parte de profesionales de la salud después de 5 años.

Proyecto Ambulancias del Río

Después de su experiencia personal, y reconociendo la creciente necesidad, Martel Fernández y otros profesionales de la salud del distrito pidieron a VASI que encabezara una campaña para lanzar varias Ambulancias del Río, botes equipados como ambulancias. El primero Ambulancia del Río se lanzó en la comunidad de Juancito el 12 de diciembre de 2020. Este cuenta con un motor de 85 HP, techo y costados cubiertos y dos camillas. El segundo y el tercer barco fueron inaugurados el 29 abril. Este es un esfuerzo colaborativo y ahora estamos recaudando fondos para equiparlos completamente con suministros médicos y equipos de ambulancia, así como para lanzar un cuarto bote. Algunas empresas que son propiedad de personas nacidas en el distrito han colaborando con la iniciativa. La entidad provincial de salud ha donado los botes y se ha comprometido en su mantenimiento y su abastecimiento de combustible. Junto con el gobierno municipal se está pagando para rehabilitarlos. VASI ha comprado los motores, los accesorios de mando y otros suministros.

Dos días después del lanzamiento del primer bote, hubo una fuerte tormenta y en la comunidad más lejana, y una mujer estaba al borde de la muerte debido a un intestino obstruido. Los profesionales de la salud partieron de Juancito, la recogieron y, después de 14 horas navegando a través de la tormenta, llegaron al hospital más cercano donde se realizó con éxito una cirugía que le salvó la vida.

Ese mismo día, un adolescente estaba postrado y al borde de la muerte por un accidente de caza en otro pueblo. Debido a que el bote ya estaba demasiado lejos evacuando al primer paciente, el joven tuvo que esperar 36 horas para ser evacuado al hospital más cercano. Luego fue trasladado en avión a un hospital regional donde extrajeron las balas de su columna vertebral.

El equipo de VASI está recaudando fondos para asegurar que las cuatro #AmbulanciasdelRío estén completamente equipadas con suministros médicos, y capaces no solo de evacuar a la gente en una emergencia, sino también de brindar atención básica y preventiva a las aproximadamente 55 comunidades las cuales no cuentan con profesionales de la salud.

También continuamos construyendo nuestra coalición de atención médica, desde VASI hemos formado un Grupo de Trabajo de Salud compuestos por médicos, profesores y estudiantes de las universidades Norte Americanas de Harvard, Stanford, George Washington y Thomas Jefferson, juntos con profesionales de salud locales y provinciales. Ahora, su misión es asegurarse de que el proyecto de #AmbulanciasdelRío sea sostenible al largo plazo, diseñar una evaluación rápida de necesidades, y junto con los residentes diseñar e implementar nuestras próximas programas de salud. Recientemente, hemos recibido una subvención de la fundación Tides que proporcionará los fondos para pagarle a jóvenes profesionales locales para ayudar a llevar a cabo la evaluación de necesidades.

Buscamos personas, organizaciones y empresas que deseen participar proporcionando apoyo logístico, financiero y/o de consultoría en especie. Lo único que le solicitamos a todos nuestros socios (además de adherir a los principios de igualdad y transparencia) es sumergirse con nosotros en esta tradición de colaboración particularmente rica en la que se respeta a los miembros de las comunidades como líderes y expertos trabajando de la mano con todos los demás.

En diciembre, Wicberto Pinedo García, miembro del Grupo de Trabajo de Salud de VASI y enfermero obstetra del hospital provincial de Contamana, señalo el efecto de la inestabilidad política en Perú (con tres presidentes en una semana), y la importancia de programas de salud locales, por lo que indicó “Nuestra población [peruana] es muy diversa tanto geográfica como culturalmente. Las políticas publicas se aplican a un nivel estándar nacional. Pero si lo aplican basado en la realidad local seria mejor. No es igual, tener un puesto de salud en la costa con todas las carreteras etc. y un puesto de salud en la selva, donde no hay carretera.” Pinedo García, nació en Nuevo Dos de Mayo, una de las comunidades fundadores de VASI.

Larry Manuyama Sharihua, un enfermero obstetra, caminando la última parte del camino hacía la comunidad indígena de Santa Rosa en diciembre 2020 cargando jabón, alcohol, gel, y oximetros.

Desolación, pérdida y resiliencia juntos

La historia del Covid-19 en la Amazonía, como en el resto del mundo, ha sido una historia de devastación y pérdidas. Sin embargo, también es una historia de resiliencia y de comunidad, en la que todos, desde los médicos, enfermeras, promotores de salud, que trabajan por poco o sin ningún salario, miembros de la comunidad e individuos e instituciones de varios continentes hacen parte.

La misión de VASI es apoyar a las comunidades rurales y marginadas mientras estas se empoderan y crean futuros sostenibles. Vemos que la salud y el bienestar de los humanos y de los ecosistemas son altamente interdependientes, y creemos que trabajos que reconocen esto tienen la oportunidad de tener un impacto enorme.

Como nuestra junta directiva local nos recuerda constantemente, caminan todo el día sin pago para asistir a las reuniones no solo para ayudar a sus propias comunidades. Reconocen el papel fundamental que desempeñan sus comunidades, y la Amazonía en general, en la mitigación del cambio climático y la protección de la biodiversidad. Quieren crear un modelo de trabajo liderado por la comunidad que pueda expandirse a comunidades de cualquier parte del mundo. Y esa es la única forma en la que vamos a combatir los desafíos de nuestro tiempo juntos.

El 28th de enero en el pueblo de Curarina, Dra. Karla C. Robles Baradoza en una campaña para llevar atención médica preventiva y básica a las comunidades remotas.

Reconocemos que ReVista en general sola acepta ensayos de autoría individual en primera persona en Ojos en Covid-19. Honramos esta tradición y el poder de estas historias. Dicho esto, esta historia fue realmente escrita por los cuatro autores.

Para donar a la campaña #AmbulanciasdelRío de VASI, puede hacer clic aquí: https://bit.ly/HelpFundRiverAmbulances. Si desea participar directamente o tiene preguntas, comuníquese con Nancy Dammann, en nancy@proyectovasi.org.

Spring | Summer 2010, Volume IX, Number 2

Samantha Neville, Harvard class of 2019, is a volunteer communication intern with VASI. Samantha conducted the interviews with Elizabeth Martel Fernández, first bringing her harrowing story to VASI’s attention.

Edgardo Gómez Pisco, VASI’s co-executive director and local facilitator, and Nancy M. Dammann, (Harvard class of 1997) co-executive director and international facilitator, provided the context and engaged with Samantha in a collaborative writing process that reflects VASI’s founding values.

Penny Alegria (Harvard 2024), a VASI volunteer communication intern, worked with Samantha Neville to provide the translation into Spanish.

Samantha Neville, clase de Harvard de 2019, está haciendo una pasantía en comunicación voluntaria con VASI. Samantha entrevistó a Elizabeth Martel Fernández y grabó su historia y la compartió con VASI y tradujo el articulo a español.

Edgardo Gómez Pisco, codirector ejecutivo y facilitador local de VASI, y. Nancy M. Dammann (clase de Harvard de 1997, codirectora ejecutiva y facilitadora internacional), proporcionaron el contexto y participaron con Samantha en un proceso de escritura colaborativa que refleja los valores fundamentales de VASI.

Penny Alegria (clase de Harvard de 2024) está haciendo una pasantía de comunicación voluntaria con VASI trabajó con Samantha Neville para realizar la traducción.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...