About the Author

Miriam Heredia is a lawyer that has been working for human rights effectiveness in Mexico, a Mason Fellow, and a Mid-Career Master in Public Administration at the Harvard Kennedy School. She previously worked at the Attorney General of Mexico as Deputy Director General addressing human rights violation cases before international bodies and the Inter American Court of Human Rights.

Acerca del Autor

Miriam Heredia es una abogada que ha trabajado por la eficacia de derechos humanos en México, Mason Fellow y Maestra en Administración Pública de la Escuela de Gobierno John F. Kennedy de la Universidad de Harvard. Previamente trabajó como Directora General Adjunta en la Procuraduría General de la República en México, coordinando el litigio de casos de violaciones a derechos humanos frente a mecanismos internacionales y la Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos.

Covid-19 in Mexico

Magnifying the Unresolved Agenda in the Penitentiary System

There is no doubt that crises generate great turning points in societies. However, there are also subtle moments of change, which, although they may not seem significant when they happen, can determine our future and reveal a path for us to follow.

Since I was little, I felt a strong call towards defending justice. Even when I did not know fully the meaning or dimension of the concept. This led me to experience moments of inflection in my life; some simple and apparently irrelevant—such as being the first student suspended in elementary school for confronting classmates who were bullying a friend of mine—as well as others of deep affectations, such as facing threats as a human rights lawyer. All those moments, the obvious and the apparently insignificant, consolidated my vocation to advocate for those who believe they have no voice to claim injustices.

Even with that call clear, I never imagined that facing a crisis like Covid-19 would end up reaffirming it with greater stamina. During Juliette Kayyem´s Crisis Management and Mitigation course at the Harvard Kennedy School, we learned that “crises will always be a magnifying reflection of existing systemic shortfalls.” Those words had a special resonance when I began to remember my experiences monitoring the human rights situation in the Mexican prison system. I was genuinely concerned about how the system’s shortcomings could be potentiated in this emergency context.

My knowledge of prison life came early in my professional path. In 2013, the Congress of the State of Michoacán, Mexico, issued a call to form a new Citizen Council to advise the State Commission on Human Rights. Although I was 26 years old, I participated. Being the youngest contender, was a fact that raised doubts for almost everyone involved in the process -including myself-, fearing that maybe I would not have enough experience to face a challenge which carried a serious level of responsibility.

Nevertheless, I was appointed to serve on the Council. The post was honorary and pro bono, nevertheless implied a whole new human rights strategy set by the newly elected members. I wanted to participate in such a strategy by evaluating the local prison system. It was a huge challenge in which it was difficult to know where to start, but it could also be translated into an opportunity to learn first-hand about the precarious and unworthy situation that I already sensed people in prisons lived. Thus I could be able to think of effective mechanisms to improve the quality of life of the inmates in general, and particularly, to denounce cruel, inhuman and degrading practices that, allegedly were routinely committed, to the extent that they were already normalized.

The prison assessments carried out by the Human Rights Commissions (in human rights jargon commonly known as Ombudsman) aim to monitor and expose the level of compliance with human rights standards, as well as the shortcomings detected. In them, compliance with such standards is evaluated through authorities’ questionnaires, interviews with inmates and graphic documentation. The assessment items generally are the following: what is the legal situation of the inmates, what measures exist to guarantee a dignified and safe stay, what provisions guarantee their physical and mental integrity, and what are the governance structures for maintaining the order. Additionally, it should be evaluated whether different measures are implemented for people in special situations of vulnerability, such as the elderly, pregnant women, people belonging to indigenous groups, people with different sexual orientation and people that have special health conditions.

During my inspections—which we established randomly and unannounced— I found myself facing a reality full of deficiencies and mainly forgetfulness. The previous inspections were periodic, which gave the prison authorities the opportunity to hide certain circumstances, whether they were about the infrastructure or the physical integrity of an inmate. What could not be hidden in any way, whether in a scheduled inspection or in a unannounced one, were the following phenomena: prisons do not usually have an updated detainee registry, or a medical station with sufficient personnel and medications, a physical separation between the accused and sentenced ones, decent places for conjugal visits and the necessary capacity to house all inmates without facing overcrowding.

Likewise, the jurisdictional and non-jurisdictional mechanisms that exist against acts of prison authorities, are out of reach of the prisoners, whether for fear of reprisals or lack of financial resources. I remember vividly the resistance of a prison’s Director to grant us access to the maximum-security area, so that we could carry out the inspection. When we got through, after various confrontations, we found an elder person who could barely move and say his name. With his arms crossed over his belly and evident pain, he told us that he had been requesting urgent medical attention for more than a month now, and that had been ignored at all times. He had a part of the intestine exposed and apparently was seriously infected.

Despite there are cases as outrageous and evident as the one cited above, there are many other practices that can hardly be detected and reported. Cruel, inhuman or degrading treatments are extremely difficult to document. Providing rotten food, baths with ice water, removing blankets in extremely cold weather, taking the population out in the sun for only ten minutes, prolonged isolation and practices that tend to nullify the personality, are some of the most frequent practices. Unfortunately, these yet unmet systemic failures are magnified considerably in the face of a crisis such as Covid-19.

In Mexico, a “State of Emergency” has not yet been decreed as it is mandated by the article 29 of our constitution, which aims to grant certainty about lawful restrictions on specific fundamental rights, so that authorities can be able to adequately face the emergency. However, the outbreak of Covid-19 did accelerate in the General Congress the promulgation of an “Amnesty Law” that was already being discussed months before the pandemic. Said Law, published on April 22, 2020 and exclusively federally applicable, grants “amnesty” in favor of people who were prosecuted or sentenced in 6 circumstances: abortion, drug trafficking committed by people in vulnerable situations, members of indigenous groups who did not had proper legal defense, robbery without violence and sedition.

In this regard, the executive branch has 60 working days to create a Commission empowered to review said requests for release, which later shall be further reviewed by a judge. It should be noted that such a law was one of the expected promises made by the current President of Mexico, when he was campaigning, in order to combat violence and promote a “pacification process” in the country.

Unfortunately, this legislation is far from meeting the needs of the prison system and facing the health implications spurred by Covid-19. In addition to questioning whether this instrument actually constitutes a legal mechanism that prevents criminal prosecutions in order to achieve peace, or if it is just a desperate measure of early release in the face of the Covid-19 contingency, it is imperative to mention that it fails to understand the precariousness that is accentuated by the pandemic we are facing.

The overcrowding in Mexican prisons will not cease to exist. The Commission will be created in at least 3 months and there are no regulations that specify the administrative or health procedures to be followed. Nor have the necessary powers have been issued so that certain federal judges can evaluate such amnesty requests. According to the National Human Rights Commission, 85% of the prison population are prosecuted by local and not federal crimes. For example, the crime of abortion as well as that of robbery without violence, are generally prosecuted at the local level, which is why the majority of women who have been penalized for exercising their right to decide, as well as offenders for non-serious crimes, will not be able to enjoy the benefits of the said Amnesty Law.

Likewise, in order to demonstrate that a person belonging to indigenous groups did not have the proper legal counsel in their native language, or that a person found himself in a vulnerable situation when they were trafficking narcotics; anthropological, linguistic, social and psychological, expert opinions are required, which are hardly available to this population even under normal circumstances. Therefore, we cannot even speak of an approximate number of people that could be benefited to depressurize the saturated detention centers throughout the country.

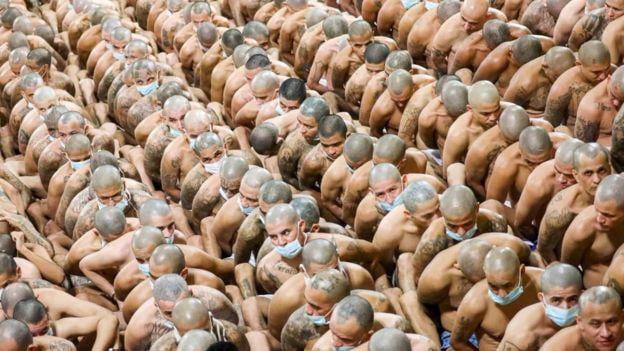

Additionally, the insalubrious conditions of the prison centers have not been mitigated and this considerably enhance the rate of infections. This was already reiterated by Human Rights Watch on April 2 and by the International Committee of the Red Cross, since throughout Latin America the lack of soap, water, chlorine and other supplies necessary to prevent contagions has been documented during this pandemic. It should be noted that these shortcomings do not put at risk only the people deprived of their liberty, but their relatives, medical personnel, defense attorneys, security agents and any kind of visitor. We also do not have approved protocols for admission, case detection, isolation, remissions and mitigation due to a Covid-19 contagion. In addition, the pandemic is causing deep affectations to the mental health of both the inmate population and their custodians. The perception of the risk of contagion and the restriction in visits catalyze fights and increase the risk of rioting. It is not a coincidence that we have seen this phenomenon in Venezuela, Colombia and Peru, as well as the iconic photo of the massive jailbreak in Brazil.

To these material and logistical challenges, we can add the deficiency of the authority to make the right to information and accountability effective. If both the numbers of people infected and killed by Covid-19 in Mexico are in dispute, much less do we have effective mechanisms to know the number of infected people and deaths -as well as the evaluation of the existing risk- in each penitentiary center. Stories of women looking for their husbands and loved ones without obtaining any kind of answer, begin to be a common denominator. There is no public list of the hospitals to which inmates can be transferred or of those centers that do have special spaces for medical isolation – not disciplinary – and what specific security measures will be imposed, in order to provide certainty to their relatives.

Despite having international guidelines such as the Tokyo Rules and the Mandela Rules, the gap for people in our prisons to live under decent conditions and under adequate security measures continues to be abysmal. The crisis we are facing is not only a “health emergency”, it constitutes a series of events that reveal systemic challenges that have been historically neglected and forgotten, including the importance we place on the effectiveness of human rights in the Mexican prison system.

It is hard to visualize all the great social changes that this pandemic will generate, but I do not doubt that it will awaken individual reflections that will hold future significance and that can be identifiable as “determining factors” many years later. Perhaps, apparently irrelevant moments like the one I lived when I was a child and was suspended, can outline our life paths. When I explained to my parents what had happened, they said, “When someone tries to silence another person, you have more reason to intercede and speak out.” Fewer people have as little opportunity to raise their voices – and ears that want to hear them – as the prison population. Nelson Mandela said it well: “It is said that no one truly knows a nation until one has been inside their jails. A nation should not be judged by how it treats its highest citizens, but those that have little or nothing.”

Covid-19 en México

La magnificación de la agenda pendiente del sistema penitenciario

Por Miram Heredia

No hay duda en que las crisis generan grandes momentos de inflexión en las sociedades. Sin embargo, también existen sutiles momentos de cambio, que aunque no parezcan significativos cuando suceden, determinan nuestro porvenir y nos develan un camino a seguir.

Desde pequeña sentí una especie de llamado a la defensa la justicia, aun cuando no conocía ni el significado ni la dimensión del concepto. Eso me llevo a experimentar momentos de inflexión en mi vida; unos sencillos y aparentemente irrelevantes—como ser la primera alumna suspendida en la escuela primaria por confrontar a compañeros que molestaban a una amiga—como otros de profunda afectación, como fue el enfrentar amenazas como abogada defensora de derechos humanos. Todos esos momentos, los evidentes y los aparentemente nimios, consolidaron mi vocación por abogar por aquellos que creen no tener voz para reclamar injusticias.

Aun teniendo claro ese llamado, nunca imaginé que el enfrentar una crisis como el Covid-19 terminaría por reafirmarlo con mayor vigor. Durante el curso de Mitigación y Manejo de Crisis de Juliette Kayyem de la Harvard Kennedy School, aprendimos que “las crisis siempre serán un reflejo magnificador de errores sistémicos ya existentes”. Esas palabras tuvieron especial resonancia cuando comencé a recordar mis vivencias al monitorear la situación de los derechos humanos en el sistema penitenciario mexicano, y me despertaron una genuina preocupación al imaginar cómo las falencias del sistema podrían potenciarse en este contexto de emergencia.

Mi conocimiento sobre la vida en prisión llegó pronto en mi vida profesional. En 2013, el Congreso del Estado de Michoacán, México, emitió una convocatoria para integrar un nuevo Consejo Ciudadano que asesorara a la Comisión de Derechos Humanos del Estado. Aunque tenía 26 años, contendí para el cargo. Era la candidata más joven, lo que generó extrañeza entre algunos, y generó dudas a casi todos los involucrados en el proceso -incluida yo misma-, temiendo no contar con la experiencia para afrontar un reto de ese nivel de responsabilidad.

No obstante ello, fui designada para integrar el Consejo. El cargo era honorífico y gratuito, pero implicaba la elaboración de una estrategia totalmente nueva entre todos los miembros recién electos. Yo quise participar en tal estrategia evaluando el sistema local de prisiones. Era un reto enorme en el que era difícil saber por dónde empezar, pero para mí significaba una oportunidad para conocer de primera mano la situación precaria e indigna que intuía se vivía en las cárceles, y así poder pensar en mecanismos efectivos para mejorar la calidad de vida de los internos en general, pero particularmente, para denunciar las prácticas crueles inhumanas y degradantes que -se decía- se cometían habitualmente, al grado de encontrarse ya normalizadas.

Los diagnósticos penitenciarios que efectúan las Comisiones de Derechos Humanos (Ombudsman) tienen como objetivo evaluar y exponer el nivel de cumplimiento de estándares de derechos humanos, así como las falencias detectadas. En ellos, se evalúa el cumplimiento de tales estándares a través de cuestionarios a las autoridades, entrevistas a los internos y documentación gráfica. Los rubros generalmente utilizados son: en qué situación jurídica se encuentran las personas privadas de libertad, qué medidas existen para garantizar la estancia digna y segura, qué provisiones garantizan su integridad física y mental, y cuáles son las estructuras de gobernanza para el mantenimiento del orden. Adicionalmente, debe evaluarse si en tal prisión son implementadas medidas diferenciadas para personas en situación especial de vulnerabilidad, como los adultos mayores, mujeres embarazadas, personas pertenecientes a pueblos indígenas, personas con diferente orientación sexual y personas con necesidades de salud especiales.

Durante mis inspecciones -las cuales establecimos con base en un sistema aleatorio y sorpresivo-, me encontré frente a una realidad colmada de deficiencias y olvido. Las inspecciones previas eran periódicas, lo que daba oportunidad a las autoridades penitenciaras para ocultar ciertas circunstancias, ya fuesen deficiencias de infraestructura o la integridad física de alguno de los internos. Lo que no podía ocultarse en forma alguna, ya sea en una inspección programada o en una sorpresiva, eran varios fenómenos: las prisiones no suelen contar con un registro de detenidos actualizado, una estancia médica con personal y medicamentos suficientes, separación entre los procesados y sentenciados, lugares dignos para visitas conyugales y la capacidad necesaria para albergar a todos los internos sin hacinamiento. Asimismo, los mecanismos jurisdiccionales y no jurisdiccionales que existen contra actos de autoridades penitenciarias se encuentran fuera del acceso de la población penitenciaria, ya sea por miedo a sufrir represalias, la falta de confianza en las instituciones o la falta de recursos económicos.

Recuerdo bien la resistencia del Director de una prisión para que pudiéramos realizar la inspección del área de máxima seguridad. Cuando después de confrontaciones logramos el acceso, encontramos a un adulto mayor que apenas podía moverse y decir su nombre. Con los brazos cruzados sobre el vientre y dolor evidente, nos relató que llevaba solicitando atención médica urgente por más de un mes a las autoridades y había sido ignorado. Tenía una parte del intestino expuesto y aparentemente infectado.

No obstante existen casos tan indignantes y evidentes como el anterior, existen muchas otras prácticas que difícilmente pueden ser medidas o reportadas. Las tratos crueles, inhumanos o degradantes son extremadamente difíciles de documentar. Proveer comida podrida, baños con agua helada, quitar cobertores en tiempos de frío, sacar a la población por solo diez minutos al sol, aislamientos prolongados y prácticas que tienden a anular la personalidad, son algunas de las prácticas más frecuentes. Desafortunadamente, dichas falencias sistémicas aún sin atender son magnificadas de manera considerable ante una crisis como el Covid-19.

En México aún no se ha decretado un “Estado de Excepción” como mandata nuestro artículo 29 constitucional, para otorgar certeza al restringir ciertos derechos fundamentales y poder atender adecuadamente la emergencia. Empero, el estallamiento del Covid-19 sí aceleró en el Congreso General la promulgación de una “Ley de Amnistía” que ya se discutía meses antes de la pandemia. Dicha Ley, publicada el 22 de abril de 2020 y de aplicación exclusivamente federal, otorga “amnistía” en favor de las personas procesadas o sentenciadas en 6 supuestos: aborto, tráfico de drogas cometido por personas en situación de vulnerabilidad, personas integrantes de las comunidades indígenas que no hayan tenido acceso a una debida defensa, robo simple sin violencia y sedición.

Al respecto, el ejecutivo federal cuenta con 60 días hábiles para la creación de una Comisión facultada para la revisión de dichas solicitudes de excarcelación, mismas que serán revisadas por un juez. Cabe destacar que tal ley fue una de las esperadas promesas que realizó el actual presidente de México, cuando se encontraba en campaña, para combatir la violencia en el país y promover un “proceso de pacificación”.

Desafortunadamente, dicha legislación se encuentra lejos de abatir las necesidades del sistema penitenciario y hacer frente a la emergencia sanitaria que presenta el Covid-19. Además de cuestionar si dicho instrumento en realidad constituye un mecanismo jurídico que impide el enjuiciamiento penal de ciertas conductas criminales bajo la finalidad de transitar a la paz, o si se trata de una medida desesperada de liberación anticipada ante la contingencia del Covid-19, es imperioso mencionar que falla en entender las precariedades que se acentúan ante la pandemia que enfrentamos.

El hacinamiento existente en las cárceles mexicanas no cesará de existir. La Comisión se creará en al menos 3 meses y no existe reglamentación alguna que especifique los procesos administrativos o sanitarios a seguir. Tampoco se han expedido las facultades de competencia necesarias para que determinados jueces federales puedan evaluar las solicitudes de amnistía. De acuerdo con la Comisión Nacional de los Derechos Humanos, el 85% de la población penitenciaria obedece a delitos del fuero local y no federal. Por ejemplo, el delito de aborto al igual que el de robo sin violencia son generalmente perseguidos a nivel local, por lo que la mayoría de las mujeres que han sido sancionadas penalmente por ejercer su derecho a decidir, así como los infractores por delitos no graves, no podrán gozar de los beneficios de esta Ley de Amnistía.

Al igual, para poder demostrar que una persona perteneciente a los pueblos originarios no contó con la debida asesoría y defensa en su lengua natal, o bien, que una persona se encontró en situación de vulnerabilidad al traficar estupefacientes, se requiere de peritajes antropológicos, lingüísticos, sociales y psicológicos, mismos que difícilmente se encuentran al alcance de dicha población bajo circunstancias normales. De esta forma, no podemos hablar siquiera de una cifra aproximada de población que pudiese ser beneficiada para despresurizar los saturados centros de reclusión de todo el país.

Adicionalmente, las condiciones insalubres de los centros no han sido mitigadas por el gobierno y las mismas potencian considerablemente la tasa de contagios. Lo anterior ya fue reiterado por Human Rights Watch el pasado 2 de abril y por el Comité Internacional de la Cruz Roja, ya que en toda América Latina se ha documentado la falta de jabón, agua, cloro y demás insumos necesarios para prevenir contagios en esta pandemia. Cabe destacar que dichas falencias no ponen en riesgo únicamente a las personas privadas de su libertad, sino a sus familiares, personal médico, abogados defensores, agentes de seguridad y cualquier otro tipo de visitante. Tampoco contamos con protocolos homologados de ingreso, detección de casos, aislamiento, remisión y mitigación ante las implicaciones del Covid-19. A ello se suman las consecuencias de la afectación a la salud mental de la población interna, pero también de sus custodios. La percepción del riesgo de contagio y la restricción en visitas, cataliza el estallamiento de riñas al interior de los centros y aumenta el riesgo a sufrir motines. No es coincidencia que hayamos visto dicho fenómeno en Venezuela, Colombia y Perú, así como la icónica foto de la fuga masiva en las cárceles de Brasil.

A dichos retos materiales y logísticos se adiciona la deficiencia de la autoridad para hacer efectivo el derecho a la información y la rendición de cuentas. Si tanto las cifras de personas contagiadas como muertas a causa del Covid-19 en México se encuentran en disputa, mucho menos se cuenta con mecanismos efectivos para conocer el número de personas infectadas y muertes, así como la evaluación del riesgo existente en cada centro penitenciario. Historias de mujeres buscando en dónde y en qué estado se encuentran sus esposos sin obtener respuesta, comienzan a ser comunes. No existe un listado público de los hospitales a los que pueden ser transferidos los reclusos ni de aquellos centros que sí cuenten con espacios de asilamiento médico -no disciplinario- y qué medidas concretas de seguridad serán impuestas en éstos, con la finalidad de dotar de certeza a los familiares.

A pesar de contar con directrices internacionales como las Reglas de Tokio y Reglas Mandela, la brecha para que en nuestras cárceles las personas vivan bajo condiciones dignas y bajo medidas de seguridad adecuadas sigue siendo abismal. La crisis que enfrentamos no es únicamente una “emergencia sanitaria”, sino constituye una serie de eventos que develan retos sistémicos que han sido históricamente desatendidos y olvidados, entre ellos, la importancia que le damos a la efectividad de los derechos humanos en el sistema penitenciario mexicano.

Es difícil visualizar los grandes cambios sociales que generará esta pandemia, pero no dudo que despertará reflexiones individuales de trascendencia futura y que uno identificará como determinantes muchos años después. Tal vez, momentos aparentemente irrelevantes como aquel que viví cuando era niña y fui suspendida pueden trazar nuestros caminos de vida. Cuando le expliqué a mis padres qué había pasado, me dijeron: “cuando alguien trata de silenciar a otra persona, con mayor razón uno debe interceder y hablar”. Pocas personas suelen tener tan pocas oportunidades de alzar la voz -y oídos que quieran escucharlos- como la población penitenciara. Bien lo mencionó Nelson Mandela: “Suele decirse que nadie conoce realmente cómo es una nación hasta haber estado en una de sus cárceles. Una nación no debe juzgarse por como trata a sus ciudadanos con mejor posición, sino por como trata a los que tienen poco o nada”.

More Student Views

Puerto Rico’s Act 60: More Than Economics, a Human Rights Issue

For my senior research analysis project, I chose to examine Puerto Rico’s Act 60 policy. To gain a personal perspective on its impact, I interviewed Nyia Chusan, a Puerto Rican graduate student at Virginia Commonwealth University, who shared her experiences of how gentrification has changed her island:

Beyond Presence: Building Kichwa Community at Harvard

I recently had the pleasure of reuniting with Américo Mendoza-Mori, current assistant professor at St Olaf’s College, at my current institution and alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Mendoza-Mori, who was invited to Madison by the university’s Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program, shared how Indigenous languages and knowledges can reshape the ways universities teach, research and engage with communities, both local and abroad.

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.