About the Author

Marc Leroux-Parra is a Mexican-American senior concentrating in studio film in the Art, Film, and Visual Studies department with a secondary in Government. Upon graduation, he looking to move to Washington D.C. and work in freelance/contracted writing, copyediting and tutoring before pursuing a Ph.D in Social Anthropology. He is especially interested in ethnography and social hierarchy.

Creators and Creatives

Animation in Latin America

Not long ago, June Carolyn Erlick, the editor of ReVista and my boss, casually asked me about animation in Latin America. I could not answer, which, as a Mexican-American film student at Harvard, bothered me. I knew that live-action filmmaking has a long tradition within Latin America, where renowned creators have produced incredibly creative works and yet animation is different. It is a medium of magic, living art. Animation is special because every culture engages in drawing, sculpting and coloring differently. Each animated story is a reflection of the culture distilled to a living, visual canvas of pure metaphor. A region so full of diverse stories, histories, languages, cultures and even art styles ought to be a hub of unique, creative animated works, I thought.

In the area of live-action filmmaking, robust studios crisscross the region engaged in various genres and substyles of cinema. Mexico has produced award-winning creators like Alfonso Cuarón, who brought a unique Mexican identity to his 2006 adaptation of P. D. James’ novel The Children of Men, and created a powerful—and divisive—representation of the indigenous who housekeep for the Mexican middle class in Roma (2018). Argentina’s Lucrecia Martel created groundbreaking works like La Mujer Sin Cabeza (2008), a psychological horror about a woman consumed by guilt after she ran over either a dog or a child—the film is intentionally vague. Beyond the international blockbusters are also the boutique films, the indie filmmakers, and the telenovela industry.

Soldiers pause their suppression of “domestic terrorism elements” within a refugee camp in near holy reverence in the climax of Cuarón’s The Children of Men. Photo credit Universal Studios

Yet, we do not think of Latin America when it comes to animation. When it comes to mainstream animation, U.S. animation—Disney, Pixar, and Dreamworks—and Japanese animation—Studio Ghibli, Kyoto Animation, etc—are the two primary creators which come to mind. Slightly more obscure is European animation, with a significant cult following both globally and within Europe. Next to nothing is known about animation from outside of these regions.

As I began to explore the subject, I’m finding that Latin American animation is a budding industry on the cusp of explosion. The biggest and best known studios are in South America, specifically in Brazil (Hype Animation, Mono Animation), Chile (Lunes Animation, Punkrobot, Zumbastico, Tyypo Creative Labs), and Peru (Red Animation Studios). These studios signed a memorandum of cooperation, pledging to work together and co-produce their films and series so as to better compete with European studios from Spain and Portugal.

Surprisingly, most of these studios work in children’s animation, although some have dabbled in more adult themes. These shows have been picked up by local and global children’s entertainment networks, among them DiscoveryKids, National Geographic, and Nick Jr.. They focus on telling stories not told, of women pioneers and indigenous myths and folklore. All highly emphasize diversity of character design, artistic rendition and creativity.

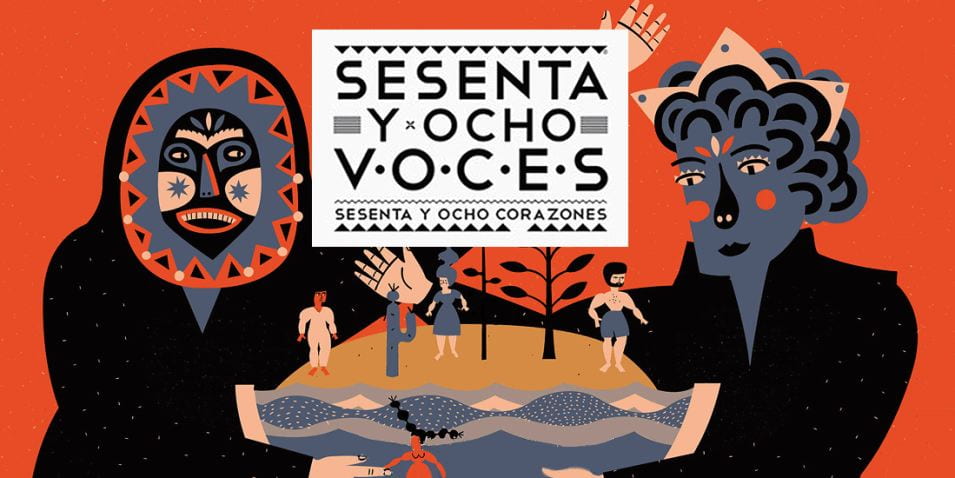

A promotional poster for 68 Voces, 68 Corazones. The still is from the short in the Zoque-Ayapaneco language from the Tabasco region of Mexico. Photo Credit: 68 Voces, 68 Corazones

In Mexico, an independent project called 68 Voces, 68 Corazones is documenting folklore from Mexico’s 68 major indigenous languages and cultures. The beauty of this project lies in its execution: the stories are narrated in the indigenous language and animated in the art style of Mexican artists. Each animation contains a different mythological story, visual presentation, and auditory component. Each short is a celebration of those indigenous cultures. While the project may not halt the widespread decimation of indigenous cultures and languages, it seeks to present their importance and beauty through the enchantment of moving artwork.

Whether children’s shows amid blossoming success or sociocultural preservation effort, their creative diversity sets them apart from emergent works in other parts of the world. In 68 Voces, 68 Corazones, Gabriella Badillo has created a template for colonially repressed peoples around the world to develop an audio-visual means of representing themselves in their own immutable ways. Zumbastico in Chile created Puerto Papel, a show which has done the unique (and masochistic in my opinion) step of stop-motion animating paper; they developed a CGI method to animate faces, used an ingenious system of magnets to streamline movements, and built their own motion-control rig. Those on the fringes of the global industry, says Zumbastico co-founder Alvaro Ceppi, need to develop their own original and technical approaches to storytelling and filmmaking.

A still from Zumbastico’s Puerto Papel. The faces are computer generated, while the bodies are physical paper. Photo Credit: Zumbastico Studios

Ceppi is right about Latin America, in more ways than simple animation. His expression of cheerful Latin American creativity applies, quite truthfully, to the overall attention Latin America is generally paid. Generally, most attention is paid to Europe, North America (excluding Mexico), Asia (particularly China and the Southeast), and Africa (specifically African problems and dysfunctions). My interest is not to criticize the attention paid—although we ought to question what is driving depictions of Africa in media to be dominantly negative—to these regions of the world; rather, it is to indicate that Latin America is a rincón of the world which people in the United States like to overlook.

I will use a current course of mine as an example. HIST 1220, The Global Cold War taught by Johanna Folland, is by all accounts nuanced and highly detailed. I am really enjoying it, and my point is not to criticize its approach. I simply cannot shake the fact that, in the pre-course list of global events associated with the Cold War that we students came up with, there were no mentions of U.S. coups in Latin America. Even now, having moved through global history from the 1890s to the 1950s and 60s, there have been no mentions of Latin America’s place in the Cold War besides Cuba. Even Trotsky’s exile in Mexico fails a cursory mention.

The reality is that Latin America is a global region which has produced rich visual contributions to history. Latin American creators share visions of the world which derive from the unique history it holds in the world. And, importantly, Latin American culture has, more than most others, defined cultural representation in animated works.

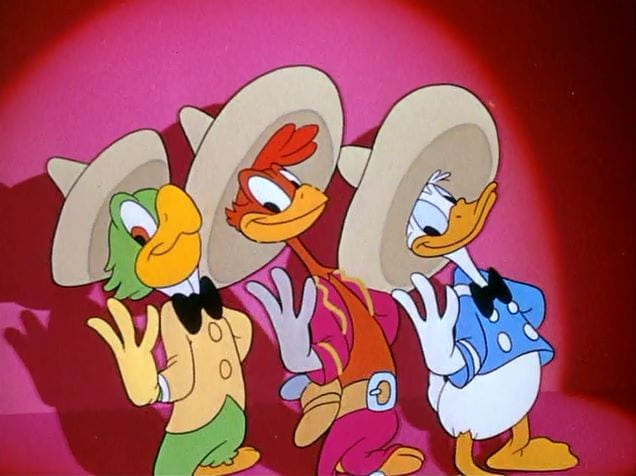

The first United Statesian foray into what I’m going to call “animated culture”—a genre of films geared specifically towards creative, visual representations of specific cultural practices, peoples, and places through animated mediums—lies with two films geared toward Latin America: Saludos Amigos (1943) and Los Tres Caballeros (1944). Both are on the canon list of “Disney Classics,” the company’s sixth and seventh titles respectively. Both films are stylistically interesting, mixing live-action sequences from Walt Disney and his company’s trips to Latin America with animated sequences starring Donald Duck. I want to highlight that neither film is truly animated culture; the films are culturally inclusive and ironically present a pretty interesting and thought out depiction of Latin America, but are more of an outsider’s homage to various cultures rather than a pure distillation of culture as animation.

Both films were propagandistic. Saludos Amigos originated from a federally funded commission the U.S. Department of State made to the Walt Disney Company. The film’s stated goal was to be a “tour of goodwill toward Central and South America.” Based on Disney’s personal tour through Latin America with his two guides, Los Tres Caballeros follows Donald Duck (representing the United States), Pancho Pistolas (representing Mexico), and José Carioca (representing Brazil) as they travel through the region. Ultimately, this was a larger, and more complex Saludos Amigos, and uses a similar fusion of live-action and animated sequences.

From left to right: José Carioca (Brazil), Pancho Pistolas (Mexico), and Donald Duck (U.S.). Carioca is a parrot from the Amazonian rainforest, and Pancho Pistolas is a rooster from a Mexican ranch. This still is from a song of the same name, and is one of the most famous scenes of the film. Credit: Disney Classics at Disney Wiki

I remember watching Los Tres Caballeros as a kid, and remember it quite fondly. Researching the two films now led to some interesting surprises. Both Saludos Amigos and Los Tres Caballeros were based on Disney’s actual travels to the region. For Saludos Amigos, the Disney team traveled to Argentina, Brazil, Chile, and Peru. The characters of Pancho Pistolas and José Carioca were based on real Latin Americans, one of whom ended up being a voice actor. In real life, Los Tres Caballeros were Walt Disney, Edmundo Santos and Aloysio Oliveira. Even more surprising was that two Mexican animators, Santos among them, returned with Disney to work on Los Tres Caballeros following his tour of Latin America. Yet Santos is not credited, and Oliveira, the voice actor for Carioca, is listed with the first name of “José.” Hardly any attention was paid to the Latin American creators.

While the films are sometimes criticized for being culturally insensitive (and some aspects of them have not aged too well), they were designed to be emblems of United Statesian goodwill rather than depictions of culture in animation. For what they were meant to be, they were well made and well received in Latin America.

In my opinion, it was Disney’s most recent foray (admittedly Disney-Pixar at this point) into animated culture which really proved to the masses just how powerful, and necessary even, a tool animation could be in cultural depictions. The success of Moana (2016) as a beautiful, landmark animated work came because it combined an iconic female lead laced with Polynesian and Oceanic cultural themes and mythos without claiming any purpose besides the telling of the story.

Moana proved to Disney-Pixar that animated culture was a potential vault of gold. You can tell from the dominant type of films that it released or announced in the years since. Bao (2018) was a clear nod to Chinese immigrant culture. Outward (2020) was obviously an ode to 1970/80s white, middle-class Americana (the D&D generation). Soul (2020) animates black jazz and community. Raya and the Last Dragon (2021) focuses on ancient Chinese culture and mythology. Luca (2021) takes place in the Italian countryside. And on November 24th, Encanto (2021) will be released, telling the magical realist story of a family from the Colombian highlands.

The Colombian family from Encanto. The story follows Mirabel Madrigal on a journey, quest, and adventure to save her family’s magical powers when they are in danger of disappearing. Photo Credit: Walt Disney Studios

Yet none of these films have created, or likely will create (although Encanto just might), the tectonic reverberations of Coco (2017). Coco transcends simple animated culture and enters the realm of cultural art. The director, Lee Unkrich, is non-Latino. His response was to combine research trips to Mexico, the personal stories of his cast and crew members, and the breaking of Disney-Pixar’s longstanding code of secrecy to include the expertise of Mexican cultural consultants in order to create what is to date the most heartwarmingly accurate animated depiction of a Latin culture from an outside source. The argument could be made for it being the best depiction of Latin American culture through animation including Latin Americans themselves.

Coco did many things right. It hired the first ever Latinx exclusive cast of voice actors. It moved away from the depictions of Mexico as being solely a party space or drug haven. It showed a magical portrayal of one of the most intimate cultural practices to exist in Mexican society. And above all, Mexicans felt like they were watching an authentically Mexican work of art.

It is important to indicate that the version of Mexico that Coco presents is universally relatable to Mexicans as a cultural work. What is even more striking is that Coco does not show this through the realities of the cosmopolitan Mexican from the large cities, and the upper-middle and upper classes. The characters of Coco are from smaller towns and pueblos. They are brown-skinned, with the fusion of European and indigenous characteristics emblematic of the more rural mestizo population. They are not indigenas, and neither are they the elite. They are characters uninterested in politics and musings of personal greatness. Ernesto de la Cruz revels in his fame, which ultimately makes him the villain. It serves as a slight critique to the individualistic and self-serving world of United Statesian success and fame.

Coco proves that it understands the ultimate hallmark of Mexican culture and cornerstone of Mexican life: la familia. La familia is not simply the literal translation of “family”; it is a set of fundamental values, world views and societal organization whose bonds are stronger than what most gringos would ever expect family to be. Dia de los Muertos is not a celebration of life after death, or even life unto death. It is a celebration of la familia, for even those who have passed live on in our family stories, our hearts, and our memories. The depiction of this reality in the magic of animation is what makes Coco feel like a cultural homage more than anything else.

The introduction to the land of the dead is visually stunning and undoubtedly Mexican. Photo Credit: Walt Disney Pictures-Pixar Animation Studios

I feel very strongly about Coco. It is the type of film that makes anyone creative want to work in the film industry. It brims with shining magic and unfettered creativity to tell a story oft untold. Thus, I am unswayed by most negative critiques of the film. Some have argued that Coco itself perpetuates the commodification of Mexican cultural symbols like calaveras and alebrijes. I think that’s reductivist; if Disney-Pixar sells Coco-themed merchandise which goes beyond what is actually in the film, then that is Disney, as a company, profiting off commodified Mexicanisms. But the film itself, I think, ought not to be judged by the extended actions of its corporate producers. In fact, from what I can tell, Mexican cultural symbols have long been commodified, with indigenous artisans who stake out their livelihoods selling handcrafted chacharas to tourists and Mexicans alike depending on the country’s cultural wealth. If anything, I hope Coco entices more families to eschew the posh resorts of the Mexican coasts in favor of culturally conscious tourism to places like Oaxaca and Puebla, where they may learn more about what Mexico is really like.

I do however, think there exists a valid critique as it pertains to Mexican creators and Mexican creations. Which Mexican animation studio, if one even were to exist, would ever be able to compete with Disney’s rendition of Dia de los Muertos? Coco was so technologically advanced, that the hand movements and finger placements of Ernesto de la Cruz’ character model were musically authentic and accurate whenever he was playing the guitar. This type of animated work costs a fortune and incredible skill, which Mexico is not poised to develop. I could not tell if Coco had Latinx animators on their team. If they didn’t, how much psychological ownership do Latin Americans, and Mexicans specifically, have over Coco? If Latinx folk were on the team, what factors contribute to stopping them from developing animation in Mexico? In the rest of Latin America? My point here is that the Disney-Pixar’s production of quality cultural works may constrain the ability for others within that culture to develop their own creations. This does not make me love Coco any less. It just makes me wish that there were more Mexican creations I could watch.

I have written this Student View in the image of what the ReVista team hopes Student Views to be. This is partly a journey of discovery about an aspect of personal identity I knew little about. It is partly a reflection on how we students observe the world to be, without focusing on research or studies that seek to define how the world is. And it is partly a personal confrontation with putting one dream, a career in film, aside through the medium of the other, writing. Over the course of the past few years, as the web-based management of Student Views has increasingly come under my responsibilities, I’ve come to understand that the best Student Views ought to be thought provoking, observant and narrative rather than pedagogical.

As much as I love working with film and animation, it is not the field I can see myself enjoying to the fullest. In this way, I admire and respect those who commit themselves to these beautiful works of magic, wonder, and distilled creativity. I especially admire those from Peru, Brazil and Chile who are creating their entire industries themselves. Animation is one of the purest forms of visual magic that humanity has ever been able to produce. Animation is the art of visual metaphor, and Latin America is a land full of promise and potential for new storytellers and their stories. And while I may never add myself to the list of Latinx creators of visual worlds, I hope to add myself to the list of Latinx creators of written worlds. And I can’t wait to watch however Latinx creatives animate their cultures and their worlds.

More Student Views

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.

Resilience of the Human Spirit: Seizing Every Moment

In the heart of Chicago, where I grew up, amidst the towering shadows of adversity, the lingering shadows of generational demons and the aroma of temptation, the key to the gateway of resilience and determination was inherited. The streets of my childhood neighborhood became, for many, prisons of poverty, plundering, crime and poor opportunity.

Andean Cultural Landscapes in Danger: The Chinchero International Airport

English + Español

Cusco stands as one of the most culturally and ecologically captivating regions globally.