“Double life” as Method

Queerness, Race and Nationality

I’ve often thought I have different versions of myself. I’m not the only one. I’ve found people may act differently in certain situations or among certain people; perhaps one is quiet and reserved around strangers, talkative and humorous around friends, and serious at the workplace. Indeed, how I perceive someone may be different from another person’s perception of the same person. In a way, one can live a double life. Using this idea of “double life,” I seek to transform it into a method, or a means of understanding and analyzing queerness, race and nationality in the context of characters in stories, both real and imagined, as well as real-life communities. By developing the concept of double life into a method, I hope to provide a greater understanding of three different individuals and communities: Ivan Monalisa Ojeda in Las Biuty Queens, Korean Guatemalans and Piri Thomas in Down These Mean Streets.

Las Biuty Queens: Ivan Monalisa Ojeda

This spring, I read Las Biuty Queens (2019), a collection of short stories by Iván Monalisa Ojeda— one of the most memorable books I’ve ever read. Ojeda, who goes by his/her pronouns, identifies as a two-spirit transgender artist and writer. Originally translated from Spanish, Las Biuty Queens traces the journey of various trans Latinx sex workers, many of them immigrants living in New York City. Though the book itself is a work of fiction, we might also read it as a fragmented memoir, written from various first-person perspectives of trans sex workers— including a character named Iván Monalisa, who is presumably the author. In the book, Iván Monalisa is a sex worker who is arrested and set to jail. When Iván is incarcerated, he/she uses two different names—Juan Cruz and Luis Rivera—as aliases. Indeed, Iván asserts, “I decided to call myself Luis Rivera. What could be more Puerto Rican than Luis? What was more Boricua than Rivera?” (16). Later, Iván declares that he/she does not want to talk about his/her past living in Chile many years ago, nor does he/she want to meet other Chileans in the jail.

This spring, I read Las Biuty Queens (2019), a collection of short stories by Iván Monalisa Ojeda— one of the most memorable books I’ve ever read. Ojeda, who goes by his/her pronouns, identifies as a two-spirit transgender artist and writer. Originally translated from Spanish, Las Biuty Queens traces the journey of various trans Latinx sex workers, many of them immigrants living in New York City. Though the book itself is a work of fiction, we might also read it as a fragmented memoir, written from various first-person perspectives of trans sex workers— including a character named Iván Monalisa, who is presumably the author. In the book, Iván Monalisa is a sex worker who is arrested and set to jail. When Iván is incarcerated, he/she uses two different names—Juan Cruz and Luis Rivera—as aliases. Indeed, Iván asserts, “I decided to call myself Luis Rivera. What could be more Puerto Rican than Luis? What was more Boricua than Rivera?” (16). Later, Iván declares that he/she does not want to talk about his/her past living in Chile many years ago, nor does he/she want to meet other Chileans in the jail.

After I finished reading the book, I compared it to other books about queer bodies that I’d read. I realized that many of them were centered on the idea of living a “double life.” Whether it be code-switching, hiding their sexuality and identity from close family members and loved ones, or choosing to physically present themselves a certain way in the presence of certain people through dress, these stories often described having to distance themselves away from a non-cisgender, non-heterosexual appearance.

In the book, Iván does not seem to present a “double life” in terms of queerness or sexuality, as he/she shares their sexual and gender identity freely with others around them in New York. Rather, I see a “double life” in another aspect of his/her identity. Iván seeks to stray away from identifying openly as a Chilean, choosing not to talk about his/her past living in Chile, and ultimately uses aliases such as “Luis Rivera” solely because he/she sees it as a stereotypical Puerto Rican name, thus allowing himself/herself to present as Puerto Rican. Indeed, the idea of a “double life” emerges in various contexts—the way Iván pretends to be Luis Rivera and Juan Cruz allows us to see the many selves Ivan has been.

Methodizing Double Life

Inspired by this book, I want to examine how a subject—whether it be an individual, a text, an idea, a concept—presents itself in contrasting ways in order to be perceived in different ways by others. Through this methodology of “a double life,” one can gain insights about how we can navigate different realities, both imagined, real, and literal, under certain guises.

The method can also reveal insights pertaining to nationality and race. Double life is particularly relevant to people who find themselves marginalized and can operate as a means to examine their stories to view the breaks in conceptualization, whether it be the conceptualization of the self or others’ conceptualization of an individual. Thus, similar to the application of double life to understand Ivan Monalisa’s character, one can also apply the method of double life to reveal the insights about the personal stories of Asian and Black Latinx.

Context and Background

Yet to understand this application of double life, it is first necessary to examine the concept of Latinidad. Scholar Walter Mignolo explores Latinidad in his book The Idea of Latin America (2005), asserting that when seeking to advance a “postcolonial identity,” “white Creoles” formed the concept of Latinidad (Flores 59). Moreover, the construct of the mixed-white and Indigenous mestizaje is directly correlated with the idea of a “united race,” which has often been touted as a key feature of Latin America. Similarly, in the article “Latinidad is Cancelled” (2021), critic Tatiana Flores explains that by assuming that mestizaje wholly encompasses Latin America, individuals who do not conform to the prevailing concept of mestizaje are deemed as outsiders (59). More specifically, Afro-Latinx and Asian-Latinx communities are cast aside in this framework (69).

Korean Guatemalans

In this way, those of Asian descent are rarely perceived as Latinx by others; the two labels are often seen as mutually exclusive. Today, there is a small community of Korean Guatemalans residing in California, and some of my friends are Korean Guatemalan. Many cannot speak Korean, as they only knew Spanish before moving to the United States. In Guatemala, they described how they were often not seen by others as Guatemalan—rather, they were seen as just Korean citizens, not Guatemalan citizens, as if being ethnically Korean discounted the fact that they had been born and raised in Guatemala. Yet when they later immigrated to the United States, they were often seen as American—Asian American and Korean American—but not Latinx American.

Therefore, in a way, they had to navigate a “double life” as they moved between countries, where their Latinx identity was often discounted and overlooked, albeit in different ways. Depending on the country, their nationality changed, from a Korean nationality to a purely U.S. American nationality, despite their true identity as Korean Guatemalans. Many expressed how they longed to be simply recognized as Guatemalans regardless of location, and in this way, this method exemplifies how double life can be imposed upon individuals against their will.

Down These Mean Streets: Piri Thomas

The theme of double life also emerges in Piri Thomas’ memoir Down These Mean Streets (1967), which explores the author’s adolescence growing up in Spanish Harlem and Long Island during the mid-20th century. Thomas grows up in a multi-racial Puerto Rican family and struggles with financial instability. Throughout the novel, Thomas details his navigation of understanding his Blackness in context of being Puerto Rican, and as an adolescent, he joins a Puerto Rican gang.

The theme of double life also emerges in Piri Thomas’ memoir Down These Mean Streets (1967), which explores the author’s adolescence growing up in Spanish Harlem and Long Island during the mid-20th century. Thomas grows up in a multi-racial Puerto Rican family and struggles with financial instability. Throughout the novel, Thomas details his navigation of understanding his Blackness in context of being Puerto Rican, and as an adolescent, he joins a Puerto Rican gang.

He moves several times—to the Long Island suburbs, where he encounters verbal racist comments from his white peers; to Harlem, where he experiences homelessness; and to the South, where he begins to understand how his Blackness affects his interactions with others.

Applying the method of double life, one can better understand how Thomas navigates his reality in the South by himself, compared to his experiences with fellow Puerto Rican Americans in New York. When Thomas is with his family, they adopt a “colorblind” attitude towards race. The subject is rarely brought up, as if they seek to avoid talking about it. Thomas’ mother is white; Thomas’ father is Black; his brothers are perceived as non-Black. His mother refuses to acknowledge that Thomas is Black, merely stating that he is “Brown,” not Black.

Indeed, in his adolescence, Thomas grapples with how his Blackness and his Latinx identity are seen as mutually exclusive to each other, and views himself as only Puerto Rican and not Black. Yet when Thomas moves to the South, this changes immediately. Others around him view Thomas as a Black American, but not Latinx. Ultimately, Thomas begins to realize how he is perceived in different ways by different people. In this aspect, depending on his immediate environment, Thomas navigates two different realities—and therefore, double life is foisted upon Thomas.

Imagining Futures

Moving forward, continuing to wield the method of “double life,” one may wonder what kind of double lives will be presented, both intentionally—as in the case of Ivan Monalisa—and against one’s will, as in the cases of Korean Guatemalans and Piri Thomas. I ask myself endless questions, centered on both a personal and multi-personal level. Will the idea that mestizaje wholly and solely encompasses “Latinx communities,” disappear, and if so, how? How might the idea of a “double life” change for queer individuals? In the midst of these questions and uncertainties, Ojeda’s words ring particularly clear: “What’s coming, I don’t know. The one thing that’s clear is that I have to keep writing.” Indeed, as individuals continue to share their lived experiences and personal stories, we may be able to create a more just, inclusive world.

L. Han is a student at Harvard College passionate about the humanities, social sciences, and global health equity. She is the daughter of immigrants and grew up on the West Coast.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

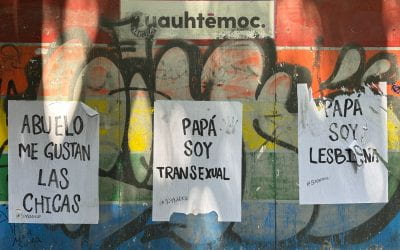

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.