ETHOS: Corporate Social Responsibility

Love for sweet milk fudge, alone, don’t explain the fact that, on an average, every Brazilian is waiting for treatment for almost five dental problems each. These dental problems are a much more serious health indicator.

Dental problems in Ipatinga, an industrial-gray, mid-size city in Brazil’s hinterland, contrast sharply with this average: according to World Health Organization ‘s latest statistical abstract, Ipatinguenses, as those from Ipatinga are called, have just 0.3 dental caries per person, a rate that is better than even Finland (1.2 problems per person). The responsible party for Ipatinga’s record is Usiminas, a giant steel maker that was privatized in 1991, and is the city’s biggest employer, with 33,000 workers. All Usiminas workers and their dependents are entitled to free dental treatment, thanks to Fundação São Francisco Xavier, a foundation maintained by Usiminas.

Usiminas is just one example among 230 selected to appear in a special edition of business magazine Exame that is devoted to the emerging market of social responsibility in Brazil. The magazine described in detail projects created by large, medium and small corporations in the areas of education, culture, health, environment and community development, as a sample of what companies are doing in an emerging tide of corporate social responsibility. Ordinary citizens, as well as companies, are beginning to understand that they must take an active role in the quest to correct long standing social problems in Brazil. In terms of philanthropic contributions, the lion’s share come from corporations: according to a study made by Instituto de Pesquisas Economicas Aplicadas (IPEA), a think tank of economic research in Brasilia, they are investing more than four billion of reais (approximately 1.6 billion dollars) annually in projects like the dental care program of Ipatinga.

With one of the worst records of income inequality in the world, Brazilians can no longer afford to wait until government takes initiative to address problems of such magnitude. A recent study commissioned by the United Nations showed that countries with income per capita close to Brazil’s rank much lower in terms of rates of poverty. Nothing less than 34% of Brazilians live in poverty, against 19% in Costa Rica, 15% in Mexico and 4% in Bulgaria.

Social problems are not new in this Latin American giant. Even after the “lost decade,” as the 1980s became known in Latin American economic history, wealth in Brazil continued to be unfairly divided, and income inequality only grew worse. In fact, social inequality is a heritage of colonial times, which dates back to slavery. Because urbanization and industrialization had different impacts on different levels of society, the distance between have and have-nots only became greater and greater with time. In the past, however, most poverty was a phenomenon of the rural world. Now, with more than 80% of Brazilians living in the cities, poverty became a more visible phenomenon.

What is really new is the way Brazilians are responding to the old challenge. Instead of turning their backs and saying that government should do something about it, society is more and more taking social problems into their own hands. A myriad of NGOs emerged in the last decades and scores of corporations are also doing their part. From the Amazon forest to the Southern pampas, volunteering has become the new buzzword among highly educated, well-off Brazilians.

Changes of these proportions rarely begin from scratch. The roots can be traced back in time to three decisive moments during the 1990s. First was Rio-92, the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro that propelled the environment to the top of the world agenda. It brought visibility for ambientalistas and activists groups of all backgrounds. After Rio-92, NGOs started to influence the public debate and, eventually, to influence public policies as well. The most recent example is the introduction in the Brazilian law of a whole new crime category, namely, environmental crimes. Ibama, the federal agency responsible for environmental law enforcement, gained credibility and power shared by few other enforcement bodies in Brazil.

Another–not less remarkable–example is how ubiquitous the word RIMA–the acronym for Relatório de Impacto Ambiental, or environmental impact report–has become in business jargon. Now, every major development project, being urban or rural, public or private, is required by law to submit a RIMA study for public debate, with accurate details about its environmental impact.

Another decisive moment was the impeachment of President Fernando Collor de Mello on corruption charges in 1993. Collor’s impeachment, the first time ever that a president was put out of office not by a military coup but by legal, constitutional means, brought the debate about ethics to the top of the social and political agenda. Since then, it is as if the level of tolerance to corruption has diminished. Until very recently, corruption was thought as a chronic, incurable social disease, like dengue fever or malaria. Now, corruption is seen as something that can and must be fought in all levels of society.

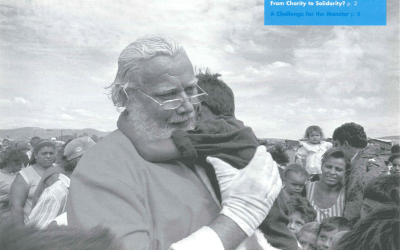

Another important turning point was the campaign against hunger that followed the impeachment, lead by human rights champion Betinho. Hunger has been one of these recurrent tragedies of the Brazilian society that are so old that they seem to be rooted in tradition, like carnaval or soccer. Hunger used to belong only to the rural world, which made it easier for urban elites to ignore it. With the dramatic urbanization experienced in most of Latin American countries in the last decades, hunger moved to the big cities and could not be ignored anymore. According to another recent IPEA study, no fewer than 23 million Brazilians currently live below the misery line–defined as having not enough to feed themselves adequately. When social drama reaches these proportions, it is easy to dismay. Pioneer Betinho refused to give up and called all who fought for the impeachment to fight this tragedy. Soon, committees against hunger started to be formed in factories, offices and corporations of all sizes; contributions materialized in bags of rice and beans, Brazilians favorite staple. Rapidly, the whole society was mobilized, and not by a populist politician promising bigger-than-life revolution, as usual in Latin America’s political history. Betinho (whose real name was Herbert de Souza) was a victim of social tragedy himself: he died in 1997, due to an HIV-infected blood transfusion.

This was the background when Ethos Institute was founded in 1998 by a group of business leaders who realized that social responsibility is a necessary condition if Brazilian society wants to survive. At the beginning, there were only eleven member companies and Ethos managed a start-up budget of 700,000 reais (equivalent to some U.S. $280,000). Three years later, more than 500 companies have joined and its budget jumped to $ 2 million dollars. Many multinational companies have joined, such as Johnson & Johnson, Alcan, Pirelli, Telefonica and Volkswagen, as well as a large and diverse group of local small and mid-size organizations. Born from such effervescence, Ethos soon gained dimensions that we believe is unparalleled in any other Latin American country.

Ethos understood that its role was to make social responsibility an ever more important issue among businesses and corporations. Beyond stimulating anew corporate ethical conscience, Ethos wanted to show companies how to align ethics with strategic thinking. To accomplish that, it has developed a set of important tools for measuring and reporting according to social ethic and responsibility standards that are finding their way to mainstream business.

Ethos’ tools are now being more widely used, as financial agents increasingly take the social and environmental profile of companies into consideration for their investments. One remarkable example is Previ, the multi-billion-pension fund of giant Banco do Brasil workers. Previ has decided to use Ethos Guidelines for Social and Environmental Reporting to gather data on 110 companies where it has investments. In another move, Unibanco Research is producing social and environmental profiles for Brazilian companies listed in the NYSE. Yet another important initiative has been launched by ABN-Amro Asset Management, which has just announced the first investment fund based on an ethical screening of corporations. ABN-Amro Ethical Fund will take into account, in selecting its portfolio, good practices related to social and environmental impact management and corporate governance. As a matter of principle, the Fund excludes stocks from alcohol, tobacco and weapons producers.

Social and ethical issues will remain on the top of the public agenda in Brazil, and not only during this year of general elections. And companies will be more and more aware of their role as vehicles for social change. And aware that this role goes way beyond traditional philanthropy. Aware that corporate social responsibility in Brazil means fighting inequality heads on. And fighting inequality also means: healthy teeth!

Spring 2002, Volume I, Number 3

Related Articles

Obras de Infraestructura Básica de Fácil Ejecución a través de la Autogestión

En el Ecuador rural y en las zonas citadinas marginales, la carencia de servicios básicos se ha convertido en un mal endémico no resuelto hasta …

Responsabilidad Social Empresarial: Algunos Hechos Que Cuentan

La Responsabilidad Social Corporativa (RSC) es una temática más bien nueva en Chile. Aún cuando se encuentran acciones filantrópicas desde tiempos de la colonia, la relación de la …

Algunos Casos en Chile

Un caso fue José Tomás Urmeneta, un empresario del siglo XIX quien, en un momento de auge del sector agroexportador chileno, en su testamento dejó asignados recursos para …