About the Author

Fernanda Agüero is a undergraduate student at Columbia University. She is interested in literary and visual depictions of the immigrant experience, as well as attempts to address educational gaps in low-income communities.

Acerca del Autor

Fernanda Agüero es una estudiante de Columbia University en la ciudad de Nueva York. Ella está interesada en las representaciones literarias y visuales de experiencias migratorias, igual que intentos de abordar las brechas educativas en comunidades de bajos ingresos.

For the First Time

When I walk barefoot in the Arizona desert, I make sure to dig my feet into the sand. The act is vulnerable, not knowing what has been buried and hidden between specks. But now, at an age when I am responsible for my own remembering, I grant myself the privilege of curling and spreading my toes. I feel it is very important to remember the sand.

The men and women around me, for the most part, feel one of two ways: half of them want nothing more than to move forward; the other half want nothing more than to go back. None of them, however, are expected to give an account of why we chose to cross the border. After miles of terror and self-doubt, when the horizon begins to share the same sight in every way and no one can tell which way is forward and which way back, it matters not if it was for a lover, a child or just the promise of a new life.

Since there’s no choice in the matter, the group automatically follows the orders of the man at the front. My sense of what he orders and the exact words he says becomes more blurry once I begin to follow the movement of the group more easily than his speech. I move around them and inspect their faces, catching glimpses of the small baby one of them hides in a tied white sheet draped around her neck. I remember to immerse myself fully and begin to see colors in the skies that reflect on the ground, adding dimension where measureless sand, in its uniformity, manages to look new with every inch.

Groans echo from members of the group as we sluggishly drag through every new step. When alarms start blaring and immigration (ICE) officers trap us with cars and helicopters, calling for the men and women to get on their knees, the boy is the only one who stays standing still. In my memory, sound is what lingers most.

I realize that, above all, in this world, I am the girl who is crossing the border, who is breaking a boundary for whatever unimportant reason, who is doing something wrong. The officers throw orders and pay no attention to the bloody leg of the injured man, which can no longer get him up. They tell the parents to keep their crying child quiet, with rifles strapped to their sides. I try to grasp what is happening by focusing my eyes on one spot and find myself suddenly face to face with the inside of a barrel. I lose sight of everything around me and freeze on the image that now faces me. I cannot bring myself to move.

But a soft tap on my shoulder suddenly lets me know that my time in the desert is up. I am helped out of my headset and headphones, as my eyes adjust back to the light of the dark room, home of the virtual world I entered into. I feel lighter after removing the black chest piece that connects the wires and batteries that power the virtual simulation and also holds the cord that the attendant could pull to indicate I was too close to the exhibit room’s walls.

I look down at the ground and spread my toes again as I try to understand how much the sand below tricked my brain into thinking that the simulation that just played was real. After traveling both domestically and internationally, Mexican director Alejandro Iñárritu’s virtual reality film “Carne y Arena,” or Flesh and Sand in English, made a stop in Dallas to challenge perceptions of the Latin American immigration journey to the United States. The gallery attendant sees me stand doe-eyed and silent and asks me how I enjoyed the exhibit. But I fail to answer her question and only ask one of my own. Have you ever tried this for yourself? To which she answers: Yes, I had to do it multiple times for my training. It never gets easier.

She ushers me into a black room where I can clean my feet and rid myself of the sand that has stuck onto them. On the other side of the room’s wall are portraits of real people who have crossed the border or been close to those who have. A teen mother, an ICE officer, and the first undocumented graduate of UCLA Law School stare at me, and when I press the button under their photos, their faces periodically blur to show a written version of their immigration narratives. At the end of the row of photos sits a black notebook, halfway full of signatures from visitors from over the last two months. Those who crossed the border wrote their stories, and those who hadn’t shared their guilt with the dozens of apologies lining the page.

Six years ago, 192 months ago, 5844 days ago—just shy of four years old, I started the real journey that inspired the exhibit I paid $35 to see that day. Although my original trek moved me through the Texas border, and my altercation with ICE happened on a highway exit rather than in the desert, the virtual experience awoke whatever small memories I had of the journey. Who had joined me when I moved through the desert myself? Who had I crossed the border with besides my mother? Although the questions could never be answered, the feeling of the journey had joined me again.

I know I remember crossing the border. How after what seemed like forever in the desert, a dozen people fit into a car and I landed in between my mother’s legs in the front seat, tucked in between a third unremembered person. I know I remember the hunger and confusion, the strain on my eyes when siren lights lit my face once we were stopped. But the desert part, which I always struggled to fully remember, came back once I saw it through the exhibit. I know I remember crossing the border, but I also know I didn’t know what crossing the border meant then. I constructed feelings about it much later, built on later memories, and then grew to understand what it meant.

Memories are short, yet their effects are long. I remember where I used to buy the candy that I liked when I was younger. Where the turtles swam by the mall and the street with the lemons that had the house with the fallen tree at the end. But memories, real memories, were not like these. These kinds of memories are built from stories and made outside of the real moment. When one recalls these moments, although visual and present, they lack the encompassing curves and certainties of those made individually, experienced fully by the self.

I leave the exhibit and walk to the passenger seat of my mom’s car. I had invited her to the exhibit with me when I found out it was in Dallas the week I was visiting, but once I told her it was a simulation of crossing the border, she laughed and immediately let me know she would not pay to experience something she had done in real life before.

She had crossed the border alone for the first time as a 21-year-old, hoping to improve the life she had in Honduras. She couldn’t see her circumstances improving as she lived with four younger siblings and raised me alone as a two-year-old. Her home was falling apart, and she knew by leaving for the United States she could potentially make her life better. She was 23 for her second crossing, with a settled life ready for her next arrival. In the year she was gone, she had found the safety she couldn’t find at home. And after leaving me with my grandmother for a year, she knew that it was time to take me to her new life in the United States. But this was the time she got caught. The border showed her, the moment she found herself detained, that no matter the reason for her crossing, she was in the wrong.

She lets me know that, for me, the exhibit only brought something new since I had not built memories of the event in the way she did. As an older, more developed, just escaped adolescence woman, she crossed the border when her memories were fully constructed by herself. She knows what she lived through; what she remembers of it is real, not formulated by the stories of others. What she says is combative, but subjecting herself to the moment that no one hopes to go through once, let alone for an artificial third time, feels natural.

I want her to validate the emotions aroused by the exhibit. I need her to tell me that I’m not crazy for feeling so strongly about something virtual, even if I’ve had the experience in real life.

Virtual reality is now tied to the metaverse and the virtual fitness classes that have populated its use. Some people said that the “Carne y Arena” exhibit changed their lives, and others refused to pay for it. I book my mom’s ticket a week after my viewing for the same $35 discounted price, $7 off for seeing it at off-peak hours. While the traveling exhibit was free in other cities, for the residents of Dallas, the twenty-minute exhibit, of which only six were virtual reality, cost more than four hours of minimum wage.

The Emerson Collective, a philanthropy group founded by Laurene Powell Jobs, the widow of Steve Jobs, funds several projects with a focus on immigration, including “Carne y Arena.” While the organization has pushed forward storytelling through various mediums, its for-profit status means that a main focus will always be the profit they earn from the projects they support.

While the exhibit comments on the hardships of immigration, highlighting the economic and safety risks that many immigrants face when making their own immigration journeys, it still charges a significantly high price for tickets. While visitors in other places, such as Washington, D.C., were able to view the show for free by just making a reservation, fees in Dallas were set between $35 and $55.

My New York job, with my New York minimum wage, lets me buy my mom a ticket with a little more than two hours of work. I send her the ticket and explain to her how to show it at the counter. I tell her she can’t pass it up. I told her I had paid for it and couldn’t get a refund, so even if she thought it was a waste of her time, it would be a bigger waste of my money for her not to go. When I return to school in New York the following week, I get a phone call from my mom on the day she sees the exhibit herself. I hope to hear of an equally impactful experience as my own, and I’m relieved when she says it reminded her of things she’d forgotten. The exhibit had made her cry.

Her memories, although fully her own, had slowly faded over the almost two decades she had spent in the States. It took the simulated version, artificial and robotic, to elicit what was real. As I remember the signatures of those who had experienced the moment in real life, as opposed to those who were living through it for the first time, the question arises of who it was made for. As those who are repeating, moving through something old, are also receiving something new.

The Oscar-winning exhibit received a Special Achievement Award for its novelty. Released originally in 2017, five years later, it continues to travel across the world, acquiring equal if not greater recognition. I balk. I encourage others to go if they can, to see what the exhibit offers them, but recognize that the price makes it unaffordable for a lot of the people who share the experience the gallery is based on. “Carne y Arena” reconnected me to my own immigrant journey, but because memory is priceless, inducing it, hopefully, won’t be.

Por la Primera Vez

Por Fernanda Agüero

Cuando caminó descalza en el desierto de Arizona, aseguró de meter los dedos de los pies en la arena. El acto es vulnerable, sin saber lo que está enterrado y escondido entre los granos. Pero ahora, a una edad donde soy responsable de mis propios recuerdos, me concedo el privilegio de rizar y separar los dedos de los pies. Siento que es profundamente importante recordar la arena.

Los hombres y mujeres que me rodean, en la mayor parte, se sienten de dos maneras: la mitad de ellos no quieren nada más que seguir adelante y la otra mitad no quiere nada más que volver. Sin embargo, no se espera que ellos den una cuenta de por qué cruzan la frontera. Después de kilómetros de terror y dudas, cuando el horizonte comienza a compartir la misma vista en todas direcciones y nadie puede decir qué camino es hacia adelante o hacia atrás, no importa si fue para un querido, un niño o simplemente la promesa de una nueva vida.

Como no hay opción en el asunto, el grupo automáticamente sigue las órdenes del hombre al frente. Mi sentido de sus órdenes y palabras exactas se vuelve más borroso cuando se vuelve más fácil seguir el movimiento del grupo que su voz. Camino alrededor de ellos e inspeccionó sus rostros, vislumbrando al pequeño bebé que uno de ellos esconde entre una sábana blanca que está atada alrededor de su cuello. Recuerdo que tengo que sumergirme completamente en el momento y comienzo a ver como los colores en el cielo se reflejan en el suelo, dando dimensión donde la arena inconmensurable, en su uniformidad, logra lucir nueva con cada centímetro.

Los gemidos del grupo hacen ecos mientras avanzan lentamente en cada nuevo paso. Cuando las alarmas comienzan a sonar y los oficiales de inmigración (ICE) nos atrapan con autos y helicópteros, ordenando que los hombres y mujeres se arrodillen, un niño es el único que se queda parado. En mi memoria, el sonido es lo que más perdura.

Me doy cuenta de que, sobre todo, en este mundo, soy la niña que está cruzando la frontera, que está rompiendo un límite por cualquier razón sin importancia, la que está haciendo algo mal. Los oficiales lanzan órdenes y no prestan atención a la pierna ensangrentada del hombre herido, la que ya no tiene la capacidad de levantarlo. Les dicen a los padres que mantengan callados a sus hijos que lloran, con rifles atados a sus caderas. Trato de captar lo que está pasando. Enfoco mis ojos en un punto y de repente me encuentro cara a cara con el interior de un barril. Pierdo la vista de lo que me rodea y me congelo en la imagen que ahora me enfrenta. No puedo moverme.

Un golpe suave en mi hombro de repente me hace saber que mi tiempo en el desierto ha terminado. Alguien me ayuda a quitarme los audífonos y el casco de realidad virtual, mientras mis ojos se adaptan a la luz del cuarto oscuro que es el hogar del mundo virtual. Me siento más ligera después de quitarme la pieza pectoral negra que conecta los cables y las baterías que alimentan la simulación virtual y también sujeta el cable que la asistente podría jalar para indicar que estaba demasiado cerca de las paredes de la sala de exhibición.

Miro hacia el suelo y abro los dedos de los pies, nuevamente tratando de entender como la arena engañó mi cerebro a pensar que la simulación ante mí era real. Después de viajar a nivel internacional, la película de realidad virtual “Carne y Arena” del director mexicano Alejandro Iñárritu hizo una parada en Dallas para desafiar las percepciones sobre la inmigración latinoamericana a los Estados Unidos. La asistente de la galería me ve parada en silencio y me pregunta cómo disfruté la exhibición. Pero no respondo a su pregunta y en vez le preguntó una de mi misma. ¿Alguna vez has probado esto por ti misma? A lo que ella responde: Sí, tuve que hacerlo varias veces para mi entrenamiento. Nunca se vuelve más fácil.

Me lleva a una habitación negra donde puedo limpiarme los pies y deshacerme de la arena que se les ha pegado. Al otro lado del cuarto hay retratos de personas reales que han cruzado la frontera o han estado cerca de quienes lo han hecho. Una madre adolescente, un oficial de ICE y el primer graduado indocumentado de la Facultad de Derecho de la UCLA me miran fijamente y a presionar el botón debajo de sus fotos, sus rostros se desdibujan periódicamente para mostrar una versión escrita de su historia migratoria. Al final de la fila de fotos se encuentra un cuaderno negro, lleno hasta la mitad de las firmas de visitantes de los últimos dos meses. Los que cruzaron la frontera escriben sus propias historias y no los que no comparten su culpa con las decenas de disculpas que alinean las páginas.

Hace 6 años, hace 192 meses, hace 5844 días, antes de cumplir 4 años, comencé el verdadero viaje que inspiró la exhibición que pagué $35 para ver ese día. Aunque mi viaje original me llevó a través de la frontera de Texas, y mi altercado con ICE ocurrió en la salida de una autopista en vez del desierto, la experiencia virtual despertó los pequeños recuerdos que tenía del viaje. ¿Quién se unió a mí cuando me mudé a través del desierto? ¿Con quién había cruzado la frontera además de mi madre? Aunque las preguntas nunca serán contestadas, el sentimiento del viaje regresó.

Sé que recuerdo haber cruzado la frontera. Cómo después de lo que pareció una eternidad en el desierto, una docena de personas entraron en un automóvil y aterricé entre las piernas de mi madre en el asiento delantero, metida entre las piernas una tercera persona no recordada. Sé que recuerdo el hambre y la confusión, la tensión en mis ojos cuando las luces de sirena iluminaron mi rostro cuando nos detuvieron. Pero la parte del desierto, que siempre luché por recordar por completo, volvió una vez que la vi a través de la exhibición. Sé que recuerdo cruzar la frontera, pero también sé que no sabía lo que significaba cruzar la frontera en ese momento. Construí sentimientos al respecto mucho más tarde, basado en recuerdos posteriores y luego llegué a comprender lo que el momento significaba.

Los recuerdos son cortos, pero sus efectos son largos. Recuerdo dónde solía comprar los dulces que me gustaban cuando era más joven. Donde las tortugas nadaban por el centro comercial y la calle con los limones que tenía la casa con el árbol caído al final. Pero los recuerdos, los verdaderos recuerdos, no eran como estos. Este tipo de recuerdo se construye de historias y se hace fuera del momento real. Cuando uno recuerda estos momentos, aunque visuales y presentes, carecen de las curvas envolventes y certezas de recuerdos hechos individualmente, experimentados plenamente por uno mismo.

Salgo de la exhibición y camino hacia el asiento pasajero del auto de mi mamá. La había invitado a la exhibición cuando supe que estaba en Dallas la semana que estaba de visita, pero una vez que le dije que era una simulación de cruzar la frontera, se rió e inmediatamente me dijo que no pagaría para experimentar algo que ella había hecho en la vida real.

Había cruzado la frontera sola por primera vez cuando tenía 21 años, con la esperanza de mejorar la vida que tenía en Honduras. No podía ver una manera que sus circunstancias mejoraran ya que vivía con cuatro hermanos menores y me criaba sola cuando tenía dos años. Su casa se estaba desmoronando y sabía que si se iba a los Estados Unidos podría mejorar su situación. Tenía 23 años para su segunda travesía, con una vida estable lista para su próxima llegada. En el año que se fue, había encontrado la seguridad que no podía encontrar en su casa. Y después de dejarme con mi abuela por un año, ella supo que era la hora de agregarme a su nueva vida en Estados Unidos. Pero este fue el momento en el que la detuvieron. La frontera le mostró, en el momento en el que se encontró detenida, que no importaba el motivo de cruzar la frontera, ella estaba equivocada.

Ella me dice que para mí, la exhibición trajo algo nuevo ya que no había construido recuerdos del evento como ella. Como una mujer mayor, más desarrollada, recién escapada de la adolescencia, cruzó la frontera cuando sus recuerdos estaban totalmente construidos por ella misma. Ella sabe lo que vivió; lo que recuerda del momento es real y no es formulado por las historias de otros. Lo que dice es combativo, pero someterse al momento por el que nadie espera pasar una vez, y mucho menos por una tercera vez artificial, se siente natural.

Quiero que valide las emociones que despertó la exhibición en mí. Necesito que me diga que no estoy loca para sentirme tan fuerte por algo virtual, aunque he tenido la experiencia en la vida real.

La realidad virtual ahora está ligada al metaverso y las clases de fitness que han poblado su uso. Algunas personas dicen que la exhibición “Carne y Arena” les cambió la vida y otros se negaron a pagar por ella. Reservo el boleto de mi mamá una semana después de verlo por mi misma con un descuento de $7, al escoger un tiempo fuera de horas punta. Mientras la exhibición fue gratuita en otras ciudades, para los residentes de Dallas, la exhibición de veinte minutos, de los cuales solo seis fueron de realidad virtual, costó más de cuatro horas de salario mínimo.

The Emerson Collective, el grupo filantrópico fundado por Laurene Powell Jobs, la viuda de Steve Jobs, financia varios proyectos centrados en la inmigración, incluyendo a “Carne y Arena”. Aunque la organización ha impulsado la narración de historias de inmigración a través de varios medios, su estado con fines de lucro significa que el enfoque principal siempre será la ganancia financiera de los proyectos que apoyan.

Aunque la exhibición comenta de las dificultades de la inmigración, destacando los riesgos económicos y de seguridad que enfrentan muchos inmigrantes, todavía cobra un precio significativamente alto para los boletos. Mientras que visitantes en otras ciudades, como Washington, D.C., pudieron ver el espectáculo de forma gratuita con solo hacer una reserva, las tarifas en Dallas se fijaron entre $35 y $55.

Mi trabajo en Nueva York, con mi salario mínimo de Nueva York, me permite comprarle un boleto a mi mamá con un poco más de dos horas de trabajo. Le envío el billete y le explico cómo mostrarlo en el mostrador. Le digo que no puede dejarlo pasar. Le dije que lo había pagado y que no podía obtener un reembolso, así que aunque pensaba que era una pérdida de tiempo, sería una pérdida de mi dinero si ella no iba. Al regresar a la escuela en Nueva York la semana siguiente, recibo una llamada telefónica de mi madre el día que ella misma ve la exhibición. Espero escuchar de una experiencia igualmente impactante como la mía, y me siento aliviada al escucharla decir que le recordó cosas que había olvidado. La exposición la había hecho llorar.

Sus recuerdos, aunque completamente suyos, se habían desvanecido lentamente durante las casi dos décadas que había pasado en Estados Unidos. Tomó la versión simulada, artificial y robótica, para regresar a lo que era real. Al recordar de las firmas del cuaderno de los que habían cruzado la frontera anteriormente, a diferencia a los que lo vivían por primera vez, surge la pregunta de quién era el público objetivo de la exhibición. Porque aquellos que están repitiendo, pasando por algo viejo, también reciben algo nuevo.

La exhibición ganó recibió un premio Premio de Mérito Especial en los Oscars por su novedad. Lanzada originalmente en 2017, cinco años después, continúa viajando por todo el mundo, adquiriendo igual o mayor reconocimiento. Animo a otros a que vayan a la exhibición si pueden, para ver lo que les ofrecen, pero reconozco que el precio la hace inaccesible para muchas de las personas que comparten la experiencia en la que se basa. “Carne y Arena” me conectó con mi propio viaje de inmigrante, pero la memoria no tiene precio, e inducirla, con suerte, igual no tendrá.

More Student Views

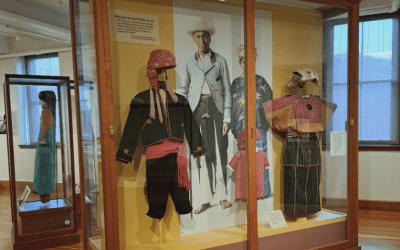

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Río Piedras: As a Desert Flower Blooms in the Night

The sunset of my first day at the Harvard Puerto Rico Winter Institute (HPRWI) painted the sky with violet and magenta. It felt as if the day had just begun.

Colombian Women Who Empower Dreams

English + Español

The verraquera of Colombian women knows no bounds. This was the message left with me by the March 30 symposium, “Empowering Dreams: 1st symposium in honor to Colombian women at Harvard.”