From the Congo River to the Inca Trail

Improved Weather Predictions for Agriculture

A river of clouds blanketing the pass as each footstep feels heavier than the last. I was hiking along the Dead Woman’s Pass on the Inca trail in Peru in November 2018. Two days of pain, and two more to go before reaching Machu Picchu. The trail consists of at least four microclimate zones ending in the tropical eastern slopes of the Andean mountains.

Due to a delicate interplay between winds carrying heat and moisture and the local terrain, the weather can change within minutes, seemingly unpredictable despite being subject to the laws of physics. Staring to the east (while embedded in clouds), I find myself contemplating how the dust and sand from West African Sahel and Sahara helps to maintain the Amazon rainforest. The connection between two continents and the ecological response to millennia of relatively stable climate resulting in a delicate balance—one that is increasingly disturbed by climate change.

View from the Inca trail near Dead Woman’s Pass, Andean mountains, Peru. Photo by Andreas Vallgren

I’m interrupted, however, by much more immediate concerns as I hear distant thunder, speeding up my steps down the mountain. I feel the urge to check my phone for details on the storm. Having designed a system to track thunderstorms in West Africa, I simply can’t help it. But I realize that there are three problems here, a basic one being no internet coverage; second, I’m on vacation (good luck with that when you are a meteorologist) and third, we don’t have a weather model for South America. I start thinking that perhaps it wouldn’t be such a bad idea to apply our forecast model on South America. Ultimately, the challenge of tropical rainfall prediction is not the only thing that connects the two continents. As I walk down the mountain, I also start taking a walk down memory lane.

Early morning view from the weather tower at Kindu airport, DRC. Photo by Andreas Vallgren.

It is back in 2003, and I sip on my morning coffee before heading out on the balcony of the “weather tower” to make the first of many weather observations. It is early morning in Kindu, eastern Congo (DRC), with the morning mist and fog quickly dissipating under the rising sun over the nearby Congo river.

Kindu Airport is waking up, with local aircrafts being stocked with live goats and chickens for transport further up the country. Congo (DRC) is vast with sparse roads that are often impassable during the rainy season, and with river transport being slow, air transport is often the only viable option.

Traditional river commute on the Congo river. Kindu, DRC, 2003. Photo by Andreas Vallgren.

I know that soon the Indian helicopter pilots—part of the UN peacekeeping mission—will swing by to hear my thoughts on the weather development.

Helicopter operated by the Indian contingent to support the UN peacekeeping operation (MONUC), 2003. Photo by Andreas Vallgren.

In the almost complete absence of any ground-based weather observation infrastructure, they rely on my direct observations with some support from satellite imagery as reliable weather forecasts are also lacking in this part of the world. I would tell the most likely scenario but warn that conditions could change rapidly after 5-6 hours and that there was little information to share beyond that. Other than the forecasts issued by the airport weather office in Kinshasa of course, usually stating 40% chance of thunderstorms on most days. The pilots would accept this reluctantly as they persist asking if I think it would be safe to fly a particular route later in the afternoon. All I could do was to smile and say “fingers crossed,” painfully aware that I was adding to the general public’s lack of trust in weather forecasts.

Author at the top of the weather tower along with some meteorological instruments at Kindu airport. Photo courtesy of Andreas Vallgren.

Despite being a weather nerd since age three, little did I know back then, that the problem of unreliable weather forecasts was systematic across the tropics, and that this problem would remain to current day, especially in Africa. It was in Congo that I fell in love with the tropics, and, given my nerdiness, the tropical thunderstorms that would bring downpours, spectacular lightning shows, cool downdrafts and that earthy smell (“Petrichor”) that follows the rain. At the time, I had no idea these passions could be pursued professionally. I ended up later co-founding a tropical weather forecasting company, Ignitia, whose mission is to reach hundreds of millions users across the tropical belt with reliable weather forecasts and alerts stretching beyond those first few hours of the tropical morning sun.

My interpretation of a thunderstorm after hearing in the Swedish news that thunderstorms were likely back in August 1987.

A photo of a Cumulonimbus cloud reflecting a distant thunderstorm in Kindu, DRC, 2003. Photo by Andreas Vallgren.

It is September 2011 and I have just finished a decade of academic studies in physics and meteorology. I’m done with theory and want to try my wings in something more practical. At this very point in time, I’m on an airplane, however, flying over the vast Sahara desert to Accra in Ghana, West Africa, to join the two other co-founders Liisa Smits (who had the guts to start a weather business on another continent from scratch) and Hafen McCormick, a former NASA employee, in building a better tropical weather forecast model. This was the birthplace of Ignitia as a weather tech start-up, starting with a printed map of West Africa (we had a printer but no chairs) to decide on model coverage and what geographic aspects to pay attention to.

Those early days (and years) weren’t particularly easy, but the complexities and hardship at times tended to reinforce and strengthen the dedication to succeed with our mission to improve tropical weather prediction. With a mix of sweat equity, soft loans and a supercomputer based in Stockholm (due to the frequent power outages in Accra), we were able to launch a basic version of our weather forecast system in early 2012. While the forecasts weren’t that impressive at that stage (forecast saying sunny as the rain was drumming on the rooftop), we were stubborn enough to continue improving our modeling for another few years (with lots of gardening to feed ourselves—I still can’t eat papaya after all those years of having to eat them).

We began to see that our modeling was able to outperform traditional global forecast models by far margins. We had to give up trying to fight the physics constraint imposed by chaos (“the butterfly effect”) and instead embrace it through probabilistic forecasts and introducing categorical forecasts. This is one of the key reasons that global models fail to accurately predict rainfall in tropical regions, as the scales of rainfall are small (circa thirty minutes and order of a few tens of miles) which means limited predictability, requiring both higher resolution, model physics improvements and probabilistic forecasts from ensemble systems to generate meaningful and actionable forecasts. Geographic factors also play important roles (e.g., coast, lakes, rivers, terrain—as experienced along the Inca trail) making it critical to provide location-specific forecasts. As the key weather differentiator in the Tropics from one village to the next and one hour to the next is rainfall, given its local nature in space and time, we asked ourselves how to reach users with location specific forecasts when connectivity and smartphones were largely absent in rural communities?

While smartphones were sparse, we found that almost everyone did have a mobile phone and that it was possible to locate which mobile cell tower a phone was connected to by partnering with mobile network providers, which both enabled users to subscribe to weather forecasts by SMS while also retrieving a proxy location to make the content location specific. The product, branded iska, was a success that we were able to scale across West Africa and which to date has been used by 2.7 million users.

Cocoa farmer in Ghana checking the iska SMS weather forecast of the day. Photo courtesy of Ignitia.

Five years on, almost on the same day of that walk down the Dead Woman’s Pass, I received a storm alert from Ignitia for my (artificial) farm outside of Santa Maria in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. It told me that there is a risk of a severe thunderstorm within the next three hours. As you have probably concluded by reading this, we embarked on a journey to expand our science to South America shortly after my return to Ghana from the Inca trail. It was relatively straightforward, especially since we started adopting AI techniques to further enhance our forecast performance back in 2018. The need for better weather forecasts was also strikingly similar, though expanded to more weather parameters than rainfall. The bigger challenge in taking our forecasts from West Africa to a country like Brazil was the vastly different landscape in terms of agriculture and the adoption of smartphones and digital tools, requiring more advanced product features, distribution channels and adapting the content to what is relevant for farmers locally.

As a reference, by 2020 an estimated 84% of Brazilian farmers were already adopting some form of digital technology in their fields, according to a study by Embrapa. Solutions include smartphone apps and smart sensors installed in the field.

However, another challenge was the presence of numerous weather data providers in Brazil. These providers have different ways of providing and improving forecast data, but most rely on global models that struggle to capture Brazil’s specific climatic patterns, their variations and the influence of the geography. Persistent long-term uncertainties, such as El Niño and La Niña events with their wide range of local and regional impacts, remain a challenge for scientists and farmers alike, especially in connection with climate change, making monitoring and impact studies areas of continued investigations.

While there is a good understanding of the average statistical impact of these phenomena, the practical application of such statistical relations in the Brazilian context is challenged by the role of the day-to-day weather (making up the statistical signals) and the limitations of many forecast providers in capturing the weather variability and providing relevant personalized impact-based guidance. For this reason, farmers are constantly searching for more effective technology and methodologies to be able to plan.

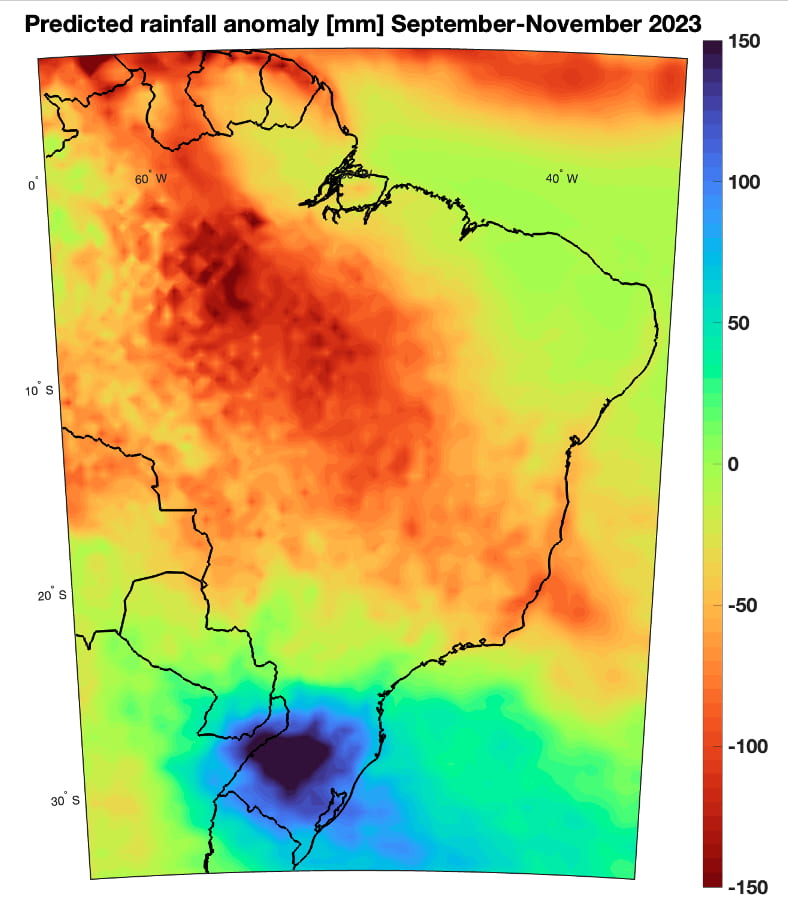

The plethora of solutions, of which many are underperforming while hyped as revolutionary, has led to fatigue and skepticism towards the solutions provided by existing climate services (and yet here we are as a new provider of such services in Brazil). One difference that may set us apart is that we had to overcome this sort of skepticism also from the start in Africa through working closely with the users and building trust over time. It is a slow journey, but one that must be embarked given the exposure to climate change and existing natural weather variability. Climate change adaptation requires persistence, creativity and innovation, of which human nature is (mostly) in possession of when it is required. This year might be a reflection of this “requirement” as we are in the middle of a strong El Niño (potentially even a rare super El Niño) whose impacts are being felt across South America. Incessant rains and floods in Rio Grande do Sul and historic drought in areas further north, such as the Amazon. We could see this trend in forecasts issued in July, highlighting the importance of informing particularly vulnerable rural communities early on.

Forecasted rainfall anomaly for September-November 2023 (departure from what is normal) in mm of rain. Red areas mean drier than normal and blue areas wetter than normal.

The last El Niño event of this magnitude was observed during the years 2015-2016 and brought extensive agricultural losses. Another consequence of that event was the largest recorded drought in the Tocantins River Basin.

With learnings of the past combined with long term forecast trends, we will likely see below normal rainfall in the central north basin during the Brazilian soybean harvest season. Having seen what our climate smart services can do to help farmers even in some of the poorest countries on earth in West Africa, we look forward to help mitigating climate shocks in Brazil and South America at large, given its weather extreme and climate change exposure, and given that it is one of the world’s most important bread baskets. Feeding the world in times of extreme weather can be particularly challenging, and we hope to help make it less so by enabling farmers with the technology and tools that track and predict thunderstorms and rainfall so that they can plan their activities sustainably with the weather rather than against it.

Looking ahead, I can’t wait to return to the Inca trail, just to try out the weather alerts. But in the meantime, I will set up an artificial location near the Dead Woman’s Pass. After all, the natural beauty of the landscape calls for stowing away phones, taking a deep breath and appreciating our natural world. With El Nino in full force, we see the signs of what a changing climate can mean at a local level and we need to adapt in many ways. Here tools such as Ignitia’s storm alerts can help, but we must not forget to try to mitigate climate change alongside, to make sure that the delicate link between Africa and South America continues to function in a way that maintains the Amazon rainforest in the future and continues to serve an eco-conscious agriculture for future food security across our planet. If this also helps the Indian helicopter pilots in DRC from 20 years ago, I may even tick one item off my to do list, though the route was one of the longer ones in life!

Andreas Vallgren, Ph.D. (KTH; Royal Institute of Technology, Stockholm, Sweden), is a Chief Science Officer and co-founder of Ignitia AB, a social impact driven deeptech weather forecasting company focusing on supporting agriculture in tropical and subtropical regions of the world, with current emphasis on building weather products tailored for South America.

Website: https://ignitia.se/

E-mail: andreas.vallgren@ignitia.se

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Agriculture and the Rural Environment

From agribusiness to climate change to new alternative crops, agriculture faces an evolving panorama in Latin America and the Caribbean.

Local “sweetening” of the Cocoa Commodity? Alternative Economies in the Peruvian Amazon

The road was nearly impassable again because of the rain.

Agro-technological Revolutions in Latin America

When we speak about a revolution in agriculture in Latin American history, most scholars rightly think of peasant revolts, land tenure struggles or commodification of crops, to name a few of the most salient themes.