About the Author

Yeeun Lee is an MSc. student in the Department of Global Health and Population at Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health. Originally from Guatemala, she received her Bachelor’s degree in Human Health from Emory University.

From Tteokguk to Tamales

I was born and raised in Guatemala to South Korean parents. A simple desayuno típico chapín (Guatemalan breakfast which includes eggs, beans, plantains, tortillas and coffee) is my comfort food. I’ve always started the new year with a bowl of tteokguk (Korean rice cake soup eaten on the first day of the New Year). During Christmas, our dining table has several dishes including tamales and kimchi, and I eat beans both savory (the Guatemalan way) and sweet (the Korean way). I’ve watched enough Korean dramas to have unrealistic romantic expectations.

Despite living outside of Korea all of my life, I have never felt that I lacked a Korean community. In Guatemala City, you’ll find Korean hair salons, churches, grocery stores, bakeries and restaurants. Whenever I’m overseas, people get surprised when I tell them that there’s a small Korean community in Guatemala and that there are many others like me. However, my experience is slightly different from that of other Korean-Guatemalans because my mom grew up in Chile and has lived in Latin America all of her life. Thus, unlike many Korean families in Guatemala, my family has close Guatemalan family friends. Language barriers are seldom an issue, and culture mixing through language, food and customs is common.

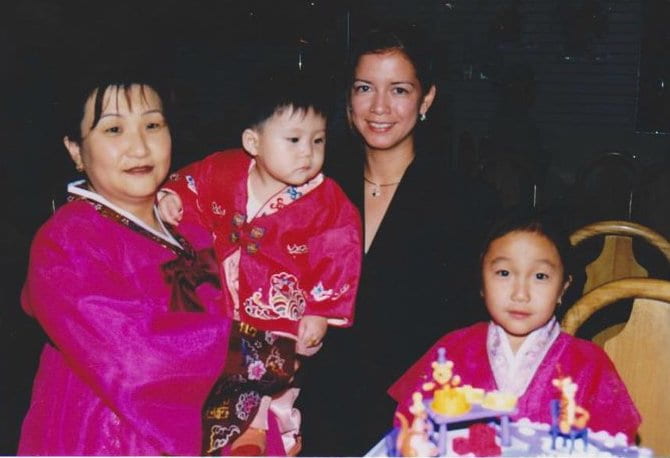

When I think of important celebrations I’ve attended, I think of both quinceañeras and doljanchis (Korean tradition that celebrates the first birthday of a baby), and growing up I’d have seaweed soup and piñatas on my birthday. Being Korean and Guatemalan makes my life more fulfilling and diverse. It is something that I am extremely grateful for and something that I’d never change even if I could. Nevertheless, while I proudly tell people that I’m Korean-Guatemalan, I avoid reflecting on my Asian Latin-American identity because it requires me to think about not only the happy and positive experiences but the hurtful and negative ones as well.

(Celebrating my brother’s doljanchi in Guatemala City)

Growing up, I hated being called “chinita”—little Chinese girl. My non-Asian friends couldn’t understand why it was such a big deal to me. As a child, I couldn’t specifically pinpoint why it bothered me so much but over the years, I’ve realized why I dislike it so much. Many people use it in a derogatory way, it feels like I’m being reduced to a characteristic of my appearance, and it makes me feel othered—perhaps even more so because although I’m Asian, I’m not Chinese. I only have a few lasting negative experiences related to my race in Latin America. But a common characteristic that most of these negative moments have is that they made me feel othered and made me want to reject my Korean side, which created difficulties and confusion with my cultural identity.

My earliest memory of feeling othered relates to my name. I remember constantly asking my parents why they didn’t give me a Spanish name or a Korean name that was easier to pronounce. While they never asked me why I was asking those questions, it mainly had to do with people deliberately mispronouncing and mocking my name. My name influenced how others treated me, which made me dislike it and affected my self-esteem. At the same time, I felt guilty for having those thoughts and feeling that way because my loved ones put so much thought into my name. As a kid, my name was one of the greatest barriers to belonging. Now that I’m older, I recognize that having a Korean name doesn’t make me any less Guatemalan. I also recognize that if someone is truly my friend, they’ll take the time to learn how to pronounce my name. While these examples may seem relatively insignificant, the amalgamation of these types of experiences at an impressionable age made me embarrassed about Korean food, Korean language and Korean media. These experiences made it hard for me to feel proud of being Korean.

Looking back, what frustrated me the most was that I didn’t fully belong to either side. I look Korean, I have a Korean name, I eat Korean food at home, but I don’t know much about Korean history. My Korean isn’t as good as my Spanish, and it’s harder for me to connect with Koreans than it is to connect with Guatemalans. Likewise, I feel most comfortable when I speak in Spanish; most of my favorite songs are in Spanish. I have lived in Guatemala all of my life, but I look Asian. I couldn’t be “good” at either, which made me feel like I was failing at both. At times I questioned if I could say that I’m Guatemalan when both my parents are Korean. Although I had many Korean-Guatemalan friends, we never talked about our Asian Latin-American identity and I never shared the struggles I had with my identity with anyone. Moreover, despite the large population of Asians in Latin America, the Asian Latin-American identity is rarely mentioned in the media. With no one to relate to and no one to talk to, I avoided thinking about my identity for a long time. Yet, the confusion and feeling that I didn’t fully belong to either remained.

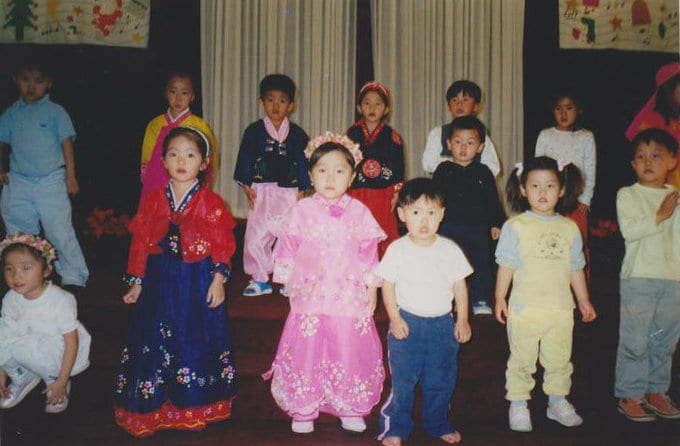

(Celebrating my birthday in my Korean preschool in Guatemala City)

Leaving Guatemala to go to college in the United States was a crucial point in starting to think about my identity. I was no longer in my bubble that consisted of the same people who already knew my background. Suddenly, I was having to tell people that I’m Korean and Guatemalan. Conversations about identity were more common in college than they were back home, which gave me opportunities to reflect on my own identity. As I started to read and listen to the stories of third-culture kids and people in similar situations to mine, I realized that even though my identity isn’t obvious, I am fully Korean and fully Guatemalan.

Coming to terms with this idea has made me more comfortable with myself and made me want to reconnect with my Korean side. I started making an active effort in improving my Korean language skills and I started asking my dad about his experiences growing up in Korea. His stories, which I used to misinterpret as him going on tangents, have taught me so much about Korean history and culture but also so much about him. Seeing how proud he is of being Korean makes me proud of being Korean.

(Picture day in my Guatemalan preschool)

At Harvard, I’ve had many opportunities to deepen my Korean-Guatemalan identity. In my classes and research position at the School of Public Health, I’ve been able to learn more about Guatemala from a global health perspective. My decision to study public and global health has been highly influenced by observing how income inequality translates into health disparities in Guatemala, especially among marginalized Indigenous populations. I’ve had the chance to learn more about the maternal health situation in Guatemala, including the role of comadronas (traditional Indigenous midwives) in providing culturally sensitive care. Through the Language Exchange Program at the Harvard Language Center, I’ve also had the opportunity to meet and practice my Korean with other Korean graduate students, which has allowed me to see things from their perspective growing up in Korea. I also joined the executive board of the Korean Student Group at the School of Public Health, something I would’ve never felt comfortable doing years ago.

As I reflect on my identity, I feel extremely grateful for it. Being Korean-Guatemalan has shaped my interests, thoughts, and experiences. It has made me more open-minded and curious about the world. And most importantly, it has allowed me to navigate a myriad of communities, spaces, and relationships.

(Celebrating Christmas in my Korean church in Guatemala City)

More Student Views

Puerto Rico’s Act 60: More Than Economics, a Human Rights Issue

For my senior research analysis project, I chose to examine Puerto Rico’s Act 60 policy. To gain a personal perspective on its impact, I interviewed Nyia Chusan, a Puerto Rican graduate student at Virginia Commonwealth University, who shared her experiences of how gentrification has changed her island:

Beyond Presence: Building Kichwa Community at Harvard

I recently had the pleasure of reuniting with Américo Mendoza-Mori, current assistant professor at St Olaf’s College, at my current institution and alma mater, the University of Wisconsin-Madison. Professor Mendoza-Mori, who was invited to Madison by the university’s Latin American, Caribbean, and Iberian Studies Program, shared how Indigenous languages and knowledges can reshape the ways universities teach, research and engage with communities, both local and abroad.

Of Salamanders and Spirits

I probably could’ve chosen a better day to visit the CIIDIR-IPN for the first time. It was the last week of September and the city had come to a full stop. Citizens barricaded the streets with tarps and plastic chairs, and protest banners covered the walls of the Edificio de Gobierno del Estado de Oaxaca, all demanding fair wages for the state’s educators. It was my first (but certainly not my last) encounter with the fierce political activism that Oaxaca is known for.