Fungi at the Ends of the Earth

Roland Thaxter in Southern South America

The southern reaches of South America, the uttermost part of the earth, have held special fascination and navigational importance for explorers since Magellan’s time. The names—Port Famine, Beagle Channel, Cape Froward, Drake Passage, Tierra del Fuego, Desolation Bay, Punta Arenas—evoke forlorn and exotic places that speak to the nature and history of the place.

Early explorers wrote of the sea, the native inhabitants and the forests. At several points in Voyage of the Beagle, Charles Darwin referred to these as the “dusky forests.” He and fellow naturalists of the Beagle days traversed these dusky forests distinctive not only in their robustness but also for the fact that they are composed of only a few southern beech tree species belonging to the genus Nothofagus. Nineteenth century naturalists collected plants and their seeds, as well as animals and fossils, but ignored small or ephemeral organisms. Aside from a few miscellaneous collections of fungi, algae, mosses and allied organisms, so-called cryptogams were largely overlooked. However, a peculiar fungus, parasitic on one of the southern beeches, came to be known for its collector as Cyttaria darwinii. It was collected partly because the indigenous people ate it. A few publications in the late 19th century helped fill the gap in the fungal record (See Spegazzini, C. 1887. Fungi patagonici. Bol. Acad. nac. cien. Cordoba 11: 5-64; Fungi fuegiani.)

Still it was not until 1906 that the beech forests truly began to yield their treasures when Harvard botanist and mycologist Roland Thaxter undertook a South American tour of discovery and exploration focusing on these neglected organisms of the dusky forests.

Thaxter (1858-1932) came from a long line of New Englanders. His childhood, rich in natural history instruction directed by his father, Levi Lincoln Thaxter, and mother, poet Celia Thaxter, led, in 1888, to a Ph.D. in Harvard’s newly founded Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. There he worked under the guidance of William G. Farlow, a protégé of Asa Gray, the primary U.S. proponent of Darwin. Thaxter served on the Harvard faculty from 1891 to his death in 1932. Although his research was varied, his principal work combined youthful entomological interests with the study of fungi that parasitize insects.

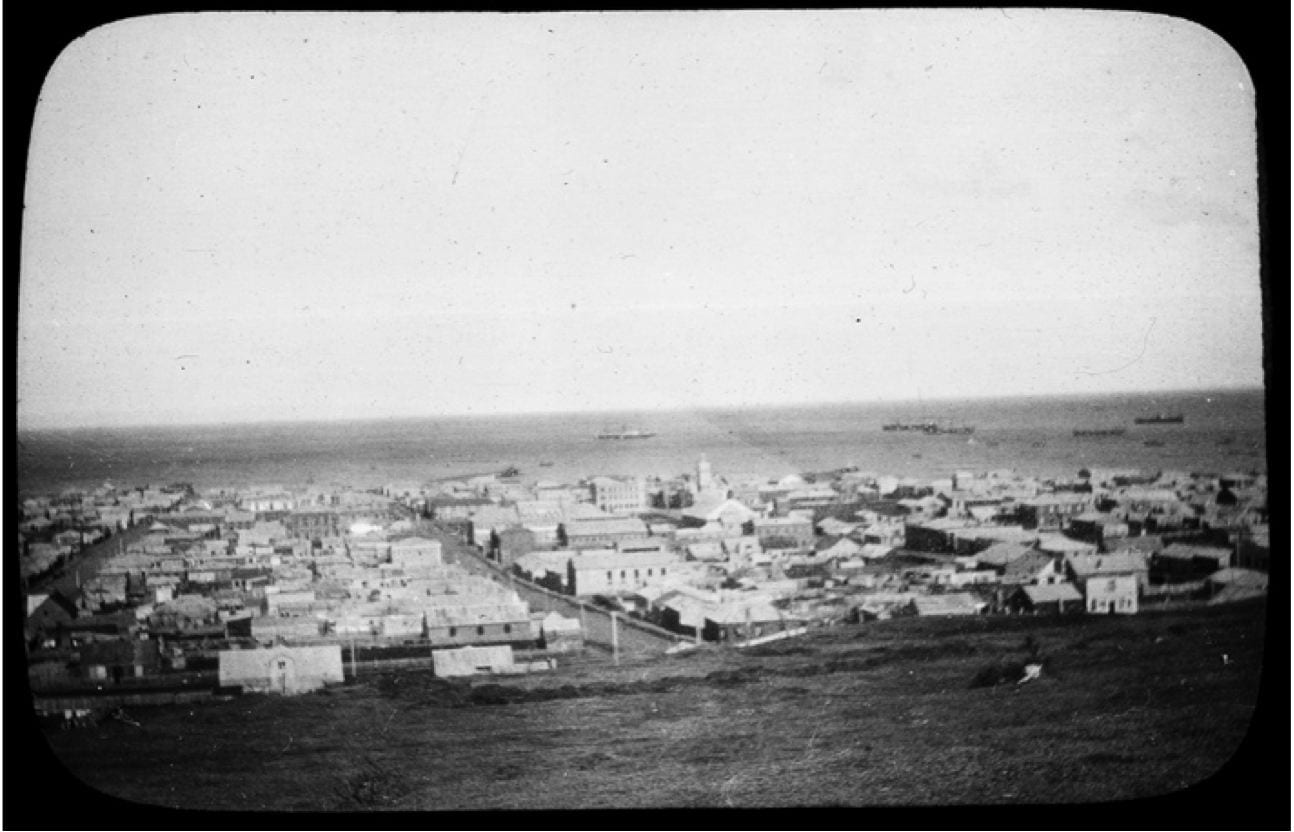

Having read Darwin and the accounts of other explorers, Thaxter arrived in Punta Arenas, Chile, on the Strait of Magellan in January 1906. In Darwin’s time, the town did not exist; it was founded in 1846 as a penal colony. By 1906, before the Panama Canal opened, it was a stopping point for ships passing from the Atlantic to the Pacific Oceans. This stop came as the midpoint in Thaxter’s proposed yearlong study trip through South America. No evidence indicates that his South American itinerary was consciously formulated in Darwin’s footsteps. Nevertheless, Thaxter visited several of the sites Darwin had seen years before. Thaxter arrived on the continent in Montevideo and then spent an extended period in and around Buenos Aires. In Chile, he worked the territories around Santiago, Concepción, and Corral. He collected insects, mostly looking and collecting their parasitic fungi; along coastal areas he gathered seaweeds. He closely observed the plants, fungi, people and landscapes he visited. Fortunately, we have his 1910 published account, Notes on Chilean Fungi, as well as the vivid, descriptive prose of his diary and many letters he sent home housed in the archives of the Farlow Reference Library and Herbarium of Cryptogamic Botany, Harvard University.

Thaxter not only concentrated on the small and obscure but, unlike earlier naturalists, he traveled alone. Staying in hotel rooms and guesthouses he carried with him all the equipment needed for his work. Alone and often ill, his letters and diary reflect his experiences in a way that may be more revealing than if he had traveled with companions. He carried gold to exchange for local currency and a revolver to protect him self from “cut throats.” “One feels,” he wrote, “as if he were landed in a paradise of cut throats and does not wonder that the traveler is almost universally advised to carry a revolver” (Diary, November 2, 1905). In writing of the gauchos, Darwin expressed a similar view, “whilst making their exceedingly graceful bow, they seem quite as ready, if occasion offered, to cut your throat.” (Voyage of the Beagle, p. 74).

In Punta Arenas, Thaxter focused his terrestrial collecting on the beech forests primarily along the Rio Minas, a small river running into the town through a deep ravine. The mine at the head of the river yielded a low-grade coal which along with wood from the forests on the perimeter of the town, heated local homes. A narrow gauge railroad brought the coal to Punta Arenas. Its tracks, and occasionally the locomotive itself, offered Thaxter access to the forest. The beech forests captivated him with their beauty, and grandeur. But it was the paradox of finding riches of the fungus realm in a forest consisting of just a few tree species in a climate appearing barely able to support the hardiest garden vegetables that proved most fascinating. Where Darwin had seen grand expanses of unbroken forests, Thaxter found them broken and fragmented, resulting from the extensive conversion of forests to grazing land as well as the harvesting of wood for fuel and construction.

To Farlow he wrote from the Hotel Oddo of the shipboard view of the landscape, “We were having typical Magellan weather and I was freezing with a bad cold. The coasts desperate looking regions, brown and bare, cold with snow ledges and never green it is said…. The beech forests neither so extensive nor the trees apparently so large as one imagines from the tales of travelers, rather scraggy in fact perhaps dull green, mostly thin.” On a later approach in 1906 he wrote in his diary, “The weather being bad, and no chance for photographs, I lay abed and rose only as we were approaching Cape Froward but yet by a favoring lift of the clouds able to see the beech forest to better advantage than on my first passage. In some places a magnificent forest especially about a sawmill not many miles from the Cape. The wind blown beeches with horizontal tops more striking on some of the points running into the Straits than any other wind blown trees I ever saw.”

He observed in Notes on Chilean Fungi that around Punta Arenas

…the whole shore of the strait, as far as one can see to the south and for many miles to the north, has been devastated by fire…. Formerly a superb forest of the Antarctic beech (Nothofagus) covered the whole region, extending from the water’s edge over a somewhat undulating plain, which gradually rises to the base of a range of hills or low mountains, the highest not 2000 feet above the sea, which form a wooded background for what is now a ghastly waste of dead trees still standing or fallen in confused heaps.

Later, after having explored on land he wrote Farlow, “I went up to these woods the day after I wrote you and had a most interesting day, walking for the first time in the Antarctic beech forest which in this place is moist, that is with swampy areas, a good deal mostly flat or slightly hilly, the trees large with an undergrowth not very obtrusive of two species of barberry and an Ericaceous low shrub mostly (also many succulent herbaceous plants) among a chaos of moss and lichen covered prostrate trunks…Everything was sopping wet and the lichens were at their best…”

The forests held many surprises for Thaxter. While most groups of fungi were represented, a few, which seemed wholly new to him, were indeed new to the scientific world. In one case, while collecting truffle-like fungi, he wrote, “In digging several times turned-up something that looked like the broken end of a big root tip, viscid, cream-colored, which proved to be a tooth-shaped fungus the apex directed upward and buried in the earth quite below the leaf cover. ‘Geodon’ I christened it.” His christening was unofficial; this distinctive tooth of the earth was finally described in 1979 as Underwoodia singeri. The author of this piece and postdoctoral fellow Matthew E. Smith traveled to Thaxter’s collecting grounds in March 2008. They found and photographed Thaxter’s “Geodon.” Smith’s photograph is rendered here as figure XXX.

Thaxter’s keen observations and lively descriptions extended beyond organisms to people and places. Punta Arenas became the “corrugated town” in his letters and diary, where he describes a first impression of the town as “low lying and extensively spreading” in a setting of “whitened skeletons.”

Today the corrugated town is situated in pasturelands with occasional wood lots. Though the “whitened skeletons” have vanished, this landscape of grasslands is dotted with stumps; nearly all show signs of being burned. The mine has long been closed. Now a National Park surrounds the area. In some of these areas the forests have regenerated.

In a day of rapid travel, of instantaneous communication, where web-pages guide nearly every undertaking, and where ATMs are found in the most out of the way places, Thaxter’s narrative reminds us that forests persist, ever changing. It is heartening to know we may still visit areas and trace Thaxter’s trail and to find some of the organisms he saw more than 100 years ago. Such observations provide insights concerning the biology and distributions of organisms that, despite the advance of time and science, remain little known. As to Thaxter, one is left with the quaint image of a solitary traveler going over his day’s finds; working away in a small room at Casa Scott, on Avenida Colon, in the rough and tumble town of Punta Arenas. After all, it was Thaxter who, during his several months in Punta Arenas, first systematically studied the fungi growing at the far end of the earth. He was fully aware of the immense change that had occurred in these beech forests Darwin had seen over 70 years before. Certainly he pondered the future of these forests, which were the source of great pleasure for him. Of the beech forests at their best he wrote, “I could not shake off a certain sense of awe on entering this forest for the first time, the elements combining to make me feel as if I had no business here and were a trespasser in the domains of some ancient wind god.”

Spring 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Donald Pfister is the Asa Gray Professor of Systematic Botany and Curator of the Farlow Herbarium at Harvard University. He is also the Dean of Harvard Summer School.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: The Sky Above, The Earth Below

When I first started working on this ReVista issue on Colombia, I thought of dedicating it to the memory of someone who had died. Murdered newspaper editor Guillermo Cano had been my entrée into Colombia when I won an Inter American Press Association fellowship in 1977. Others—journalist Penny Lernoux and photographer Richard Cross—had also committed much of their lives to Colombia, although their untimely deaths were …

Other Cities, Other Worlds

Author of a marvelous book that excavates the palimpsests of memories encrypted in the image-filled voids of Berlin, Andreas Huyssen extends his investigation of the urban imaginary in…

Dirty Secrets, Dirty War: The Exile of Editor Robert J. Cox

t may be argued that Dirty Secrets, Dirty War: The Exile of Editor Robert J. Cox should have been written three decades ago, most likely in 1981, when Cox was enjoying, as I do now, a Nieman fellowship…