Gender, Class and Power in Chile’s Anti-Trans Movement

Protect which children?

I had once again made the mistake of being on time. Despite years of living and working in Chile, my Midwestern internal clock never let me arrive anywhere on “Chilean time,” meaning I had shown up to a rally in Santiago’s Plaza Italia in January 2018 an hour or two before it would actually begin.

In my time working and researching alongside trans and gender non-conforming activists at OTD (Organizing Trans Diversities) Chile, Santiago’s prominent trans rights organization, I had put myself in some admittedly rocky situations. This morning however, I felt especially nervous. I was alone, and for the first time, I was attending an anti-trans rally to gain a better understanding of the movement.

A small but vocal minority, the anti-trans movement seemed to have outsized power, and I wanted to understand why. Despite having no stake in a proposed law establishing trans rights, they were consistently present in policy-making debates, often allowed to speak instead of trans activists. What was it about this fringe minority that was seemingly so enticing to the Chilean political class?

I came to learn that the fault line between pro- and anti-trans activists ultimately mirrors the racial, gender and class divisions at the heart of Chilean society since its beginnings. Given that the Chilean anti-trans movement is largely made up of white and mestiza, upper class cisgender women (women who were assigned female at birth and identify as such), who they are is as important as the message itself. Most of the Chilean anti-trans movement’s ideas fall into three main categories: appeals to science, conservative gender and family roles, and the fragile innocence of children. Their identities and message combine to give them political power that far outweighs their numbers, allowing them to defend their privileged place in the social structure.

A child on a leash explores the plaza against a backdrop that reads “Chile sanctions and legalizes the sodomization and abuse of children.”

The Rally

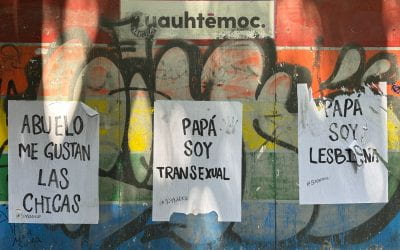

As I found some shade on that hot January morning, I thought back on the countless protests, rallies and performances I had attended in this plaza. Given its central location, many of Chile’s greatest triumphs and most tragic episodes have started here. Lampposts and exterior walls are covered in layers of posters, graffiti and wheat paste, a testament to the sheer volume of history that has been made here. In fact, it would be this same plaza, rebaptized Plaza Dignidad (Dignity Plaza), where the country’s year of protest demanding a new constitution would begin in 2019.

Accidentally arriving early was nerve wracking, as I suspected I would see many familiar—but not necessarily friendly—faces. Since I had started preliminary fieldwork in 2013, OTD and other LGBTQ+ organizations had been fighting for a national Gender Identity Law, which would enshrine rights like name and gender-marker changes and access to trans-affirming healthcare into law. The law was ultimately adopted at the end of the year.

Even at the beginning of 2018, it seemed clear that some form of the law would pass, which emboldened anti-trans voices as the clock ran out. If they could not stop the law, they were determined to weaken it as much as possible and make noise doing it. As such, whether we were in Valparaíso attending a congressional debate or walking out of a meeting with a sympathetic politician in downtown Santiago, we tended to see the same anti-trans activists and slogans wherever we went.

In this way, the rally itself was fairly unremarkable. Representatives from anti-trans organizations and churches gave rousing, sermon-like speeches into a megaphone, repeating the same slogans and pseudoscience to an uncritical crowd. And just as the rally was wrapping up, controversial travesti activist Sofía Devenir arrived with her guitar, singing Chilean folk songs with the lyrics changed to challenge the attendees.

The most recognizable speaker that day was María Pía Adriasola—la Pía, as we came to call her—wife of Chilean far-right politician and recent presidential candidate José Antonio Kast. Coinciding with her husband’s failed bid for the presidency, Pía became one of the most recognizable opponents of the Gender Identity Law.

Pía Adriasola addresses a crowd of anti-trans protestors.

Both Adriasola and her husband have the European features and particular accent of the Chilean elite. They met studying law at Chile’s prestigious Catholic University, have nine children, and are members of the conservative Catholic Schoenstatt movement. Particularly popular in Chile, the Schoenstatt movement is sometimes compared to Opus Dei for its extreme interpretation of Catholic doctrine.

Race and Class in Chile

I mention these personal attributes only to underscore divisions in Chilean society that may not be obvious to readers from other countries. While Chile has a substantial officially recognized Indigenous population, centuries of colonial rule, genocidal policy and government repression of Indigenous culture mean that most Chileans have Indigenous ancestry, but relatively few claim it. As a result, discussions of race in Chile are often hidden in the language of social class, though this is changing with the recent arrival of more Afro-Caribbean immigrants. That is, it is generally understood that whiteness goes hand-in-hand with wealth and political power in Chile.

As a blue-eyed blond in Chile, being easily read as foreign was sometimes a minor inconvenience. However, at the anti-trans rally, my whiteness allowed me to navigate the space freely, taking pictures and recording without difficulty. This was because as the Plaza filled, the crowd remained largely white/mestizo and upper class. As one organizer set up an echoing loudspeaker, another stood in the middle of a circle of attendees leading them in a lengthy, improvised public prayer. Though there were many men and children present, the faces of the movement are almost exclusively upper class mothers.

Flags with slogans like “Revolutionary Capitalism” and “Don’t Tread on Me” mix with appeals to the Ministry of Education to leave children alone.

Parents ran after sandy-blond, blue-eyed toddlers holding pink and blue balloons; vendors sold food, drinks and noisemakers; far right activists with crew cuts arrived with “Don’t Tread on Me” flags; and representatives from newly formed organizations like Padres Objetores (Objecting Parents) unfurled banners with slogans like “More Biology, Less Ideology: XX = woman, XY = man,” “Only I Raise my Kids,” and “Defend the Children.”

These anti-trans ideas are virtually identical to those driving the wave of book bans, anti-trans legislation and increased violence currently sweeping the United States. Given the growing influence of US evangelical movements in Chile, this is not a coincidence.

More Biology, Less Ideology

Though strict and separate gender roles have long been valued in Chile, this strain of anti-trans panic has come on the tails of the increasing popularity of U.S.-based charismatic and evangelical Christianity. While Adriasola herself is Catholic, she is the public face of a largely evangelical movement. Many of those present wore T-shirts and held banners representing Protestant churches, and the entire structure of the rally borrowed from U.S. revivalist traditions.

A group of anti-trans protestors engages in the laying on of hands, a popular evangelical practice.

Evangelical Christianity is popular among two groups of Chileans: upper-class Chileans, often lapsed Catholics, who view the foreign roots of the religious movement as cosmopolitan; and lower-class Chileans and immigrants, drawn in by the siren song of the Prosperity Gospel, which preaches that God rewards the faithful with wealth and abundance.

Though we sometimes think of European Catholicism as the primary colonizing force in Latin America, it’s important to understand the increasing popularity of U.S.-based evangelicalism. Despite their embrace of colonial religions, Evangelicals have been reticent to embrace other colonial institutions like evidence-based science. From evolution to the age of the Earth, they have preferred Biblical explanations to scientific ones. This makes slogans demanding “more biology” particularly intriguing.

A praying man holds a sign to the heavens that reads “More Biology, Less Ideology. XX = Woman, XY = Man.”

Importantly, biologists overwhelmingly agree that there is much more to human sexual variation than X’s and Y’s. Nonetheless, it seems that when appealing to one colonial power structure (the Church) failed, anti-trans forces attempted to appeal to another—evidence-based science—repackaging their ideas with pseudoscientific language that might be more palatable to the masses. That is, though these activists made claims to scientific truth, they were actually using the authority of scientific language to garner support for unscientific ideas. This combined with their authority as upper class Christian mothers to give them unwarranted credibility.

Only I Raise My Kids

The nuclear family (father, mother, children) has long been idealized in Chile. However, from the violence of the colonial process to the stolen children of the Pinochet dictatorship (1973-1990), the Chilean political class has historically only been concerned with the integrity of families like their own. As divorce was illegal until 2004, marriage became an unnecessary complication for many Chileans, and the makeup of families has historically been fluid and multigenerational. However, even among the elite, people outside the nuclear family play a crucial role in maintaining the family.

A white woman holding a pink balloon surveys the plaza against a backdrop of t-shirts that read “No to Gender Ideology. Only I raise my children!”

Since the colonial era, white and mestiza women have depended on the help of lower-class and Indigenous women in rearing their children. Even middle-class households in Chile often have nanas (a combination of a maid and a nanny), often from marginalized communities and dressed in checked aprons that mark them as hired help. They clean, cook and do childcare, and in many cases even live with the family. Contrary to the anti-trans slogan, upper-class Chileans rarely raise their children alone.

In monied, Christian homes, the father may be the head of the family, but the mother is the head of the household. This means she is not only in charge of childcare decisions, but also of the nana. Given the typical class and race differences between employer and employee, this relationship calls to mind dynamics between colonizer and colonized that go back centuries. Domestic workers in Chile have historically put their employers’ children ahead of their own, whom they may only see one day a week or just in time to put them to bed.

The illusion of the ideal nuclear family requires the destabilization of the domestic workers’ own families. Anti-trans appeals to gendered family roles are in fact a bid to defend their place in their social and family hierarchies. In defending “traditional” gender roles, they are in fact defending their own power within the home and family.

Defend the Children

Anti-trans activists centering the nuclear family are part of a centuries-old legacy of advocating on behalf of theoretical children, who are always heterosexual, cisgender and in need of protection from “gender ideology.” Unsurprisingly, the most controversial issue in the debate surrounding the proposed law was the inclusion of provisions for children and adolescents. Though children were eventually almost totally removed from the final text, the debate spurred a larger conversation about the rights and needs of trans children.

In the ensuing congressional sessions, trans activists cited both their personal experiences and numerous studies demonstrating that validating trans children’s gender identities markedly reduces rates of suicidality and depression. Their opponents made spurious and vague arguments that alternated between protecting trans children from potential harm and protecting (presumably cisgender) children from trans children.

A few weeks after the rally, anti-trans protestors are physically removed from the congressional gallery after repeatedly interrupting the debate of the Gender Identity Law.

The idea that children must be protected from biological and social realities is relatively new, and in Chile only those with access to private education, adequate childcare and insulation from poverty can maintain this illusion long term. In contrast, children in the country’s crowded public schools, overwhelmed foster care system and living in informal settlements cannot be similarly shielded.

End of the Rally

As the rally ended and attendees posed for a group picture, a young man walking through the plaza paused, attempting to argue with them before calling them “crazy” and flipping them off before he was roughly escorted away. Though few attendees engaged with him directly, as he faded into the distance, I heard whispers of roto and flaite, common disparaging nicknames for the Chilean lower class. Those gathered, representing some of the most privileged corners of Chilean society, were incapable of hearing him because they perceived him to be “low class.”

A passerby confronts anti-trans protestors.

There have always been two Chiles: rich and poor, European and other. While upper-class Chilean women experience the same marginalization as all women, their embrace of “traditional” womanhood grants them power within the home and family, power that is threatened by trans community’s more complicated understanding of gender. The anti-trans movement is not motivated by concern for science, family or children. Rather, it is ultimately a defense of centuries-old power dynamics that favor whiteness and upper-class femininity, giving them a political voice far greater than their numbers deserve.

Baird Campbell holds a Ph.D. in Anthropology from Rice University. His research focuses on the relationship between social media and trans and gender non-conforming activism in Chile. You can learn more about his work at bairdcampbell.com.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.