Granddaughter of a Perpetrator

Coming to Terms

I remember being in the school patio. My grandfather had been arrested the day before. I didn’t say anything about what had happened. I didn’t understand. I wanted to tell someone something, but I knew no one would understand what I was saying. In my school in 2002, they didn’t teach us anything about the history of contemporary Argentina. We didn’t talk about the coups or the dictatorships. We didn’t know anything. I didn’t know anything about who my grandfather was, but I did know that on the weekends, he went to the Military Circle Club in Olivos in Buenos Aires Province. I knew that I couldn’t say that at school. I said “the club,” but I said I didn’t remember the name.

I remember. I am seven years old, maybe even a little younger, and my grandfather shows up in our kitchen. He tells me, as always, to look inside his shirt pocket. He brought me picture cards. He always has picture cards. Sometimes he takes me to a bookstore and lets me choose some stickers or writing paper. My favorite places in the world are bookstores. I collect stickers as if they were gold. They are my most valued treasure. My grandfather always gives me little gifts.

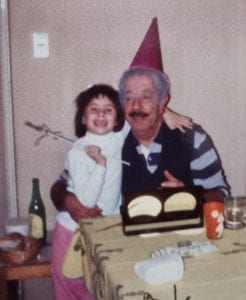

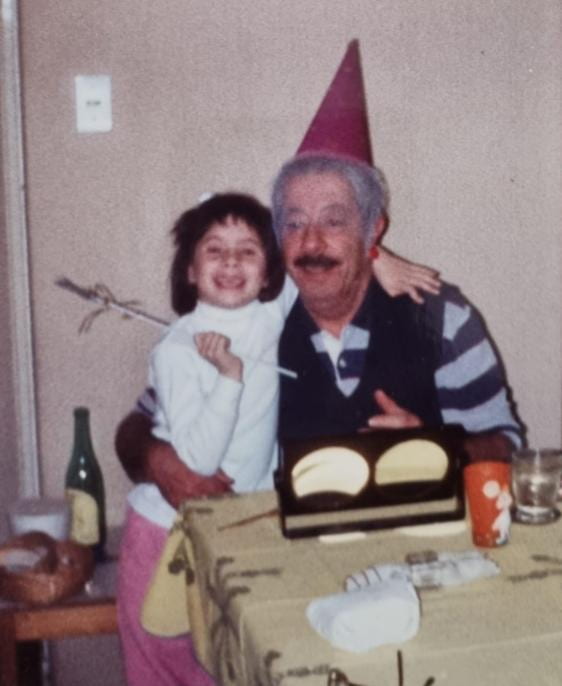

Natalia Dopazo and Orlando Oscar Dopazo. Personal Archive. 1994

I remember. I’m 20 years old and a substitute professor in Contemporary Latin American History at a private high school. We are in a program of truth and memory that takes place by the National Goverment. The first day I’m called in to substitute, I find the activity already programmed. Several people show up, including a man nicknamed “El Mono.” We are going to the clandestine detention center “El Vesubio”. We go under the highway. The next day, we go to the former ESMA, the Navy headquarters used as a clandestine center and torture where more than 5,000 people went through. “El Mono” introduces himself, and tells his history; he was a People’s Revolutionary Army Party activist; his wife was killed by being dropped out of a helicopter to Río De la Plata River; she was pregnant.

It’s October, and it’s hot. I go to the former ESMA, taking several students from the school. We are scheduled to go to the Officers’ Casino. I find my throat tightening up. I remember my grandfather’s voice, as he told me about the parties in Officers’ Casino in Cordoba or Mendoza, I can’t quite remember where. It’s not this one in Buenos Aires. I remember the photos of my grandfather and his collegues there. It’s the same type of place. The Officers’ Casino of the former ESMA operated as part of a clandestine center. They show us a place that was a darkroom or a printing operation.

Sector “Capucha”, located on the second floor of the former Officers’ Casino of the former clandestine detention center of the Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (now Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos), in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Wiki Commons

We go on another visit with students, this time to a detention center on Humberto Primo Street. The journalist Miriam Lewis was illegally detained there. They show us the terrace. The guide tells us the military let her go out there from time to time; We see the green and white awning that let her recognize the place. We also see the surrounding buildings, imagining all the eyes that must have seen this place.

I remember. It is summer, school vacation. After lunch, I have to take a nap. I lie down in a cot next to my grandparents’ bed. My grandmother pulls down the shades. She tells me the story about the bald rooster or an alligator. Sometimes when my grandmother is working, my grandfather reads to me. He tells me about the calf Pombo and his mother.

My grandfather smoked. He died of colon cancer—a cancer he never told us he had. He smoked his entire life, although he quit for a few years when he was young. He told us that after this hiatus, he became addicted again after one of his soldiers died on his stretcher after an armed confrontation.

I remember. I open my grandfather’s glove compartment. Every afternoon, before my parents came home, my grandfather would come pick me up at school in his salmon-colored Ford Falcon that was very special because it had a custom-made five-wheel drive. His car was always so very clean. I open the glove compartment and find two weapons. I don’t touch them. They are old. I tell my mother. Later, I learned he sold them. My grandmother told me that only God could know what he did and thought. And later I told her about the weapons.

View of the Ford Motor Argentina plant in General Pacheco, September 1982.

It’s New Year’s, probably 1996, my sister is a little baby, and we’re in a country farmhouse loaned to us by a friend of my parents in La Reja, Moreno. We’re going to see how my dad sets off fireworks. My grandfather and I are sitting in some small chairs at a distance, looking up at the stars, waiting for the makeshift firework show. I think I asked him what he did before for a living and he told me: I fought against subversion.

I remember. I’m 12, and every afternoon, or at least many afternoons, I spend with my grandmother. My grandparents have separated, living in different houses until my grandfather’s arrest. When he went out on bail with her as guarantor, she let him live with her to avoid jail. I learned this years later. For a time we didn’t see each other. My mother didn’t want to talk to him, but as the years went by, we began to have some sort of relationship again. We live in the same building, my grandparents on the first floor and we on the fourth. My grandfather asks me to write a paper by hand and then type it on the computer. He doesn’t know how to use a computer. He explains that in the trial they accused him of something he didn’t do; they didn’t understand the chain of command.

He didn’t kill anyone. He didn’t kill anyone. Something that my grandparents repeated to myself every so often. He’s not like Paulino Furió, this one was indeed all messed up, a violent type who beat up his kids. Your grandfather is an excellent person, they tell myself. My father, a former member of the Communist Party, tells me: what happened is that he sucked up to [General Luciano] Menendez, your grandfather didn’t want to get involved in these rackets and that’s why they stabbed him the back and sent him off to Buenos Aires in 1978. Years later, he would confes to me that he didn’t know the truth but he said that to me so I wouldn’t get upset.

Menendez went to visit my grandfather, Orlando Oscar Dopazo, at the Military Hospital in Buenos Aires where he was hospitalized for medical exams; he’d already been living under house arrest for quite a while, awaiting trial. As my grandmother tells it, the general came to the room and my grandfather pretended to be asleep; he did not want to see Menendez.

Years later in the pandemic, for the 1000th time, I try yet again to reconstruct who Orlando Oscar Dopazo was, the person whom journalist Horacio Verbitsky mentions on the back cover of Página 12 in 2004. It seems that my grandfather was present at a massacre in Cordoba. I tried to search databases for those who had commited crimes against humanity. I enter in his last name; I know that he died before he actually received a sentence. How many cases are there, three, four? What is the difference between the cases? What is the mega-case of La Perla, a clandestine detention center in a rural area outside Cordoba. My boyfriend at the time told me about this center. Was my grandfather responsible for the kidnapping of the journalist Paco Urondo? What was my grandfather’s rank? Colonel? Liuetenant Colonel? I knew that he studied at the War College. That he came from a humble family in Entre Ríos, and that he wanted to go to the War College ever since he was a little boy. Not everyone got in. I knew that he was very intelligent. According to my dad, he was a fanatic committed to acts of violence. I open the search engine once again and this time I find a document from the Argentine Secretary of Human Rights that talks about organizational charts. It’s a PDF. I press CNTRL+F: Dopazo. Up comes the term COT in 1976 in the Intelligence Division G2.

When you look a monster in the eye, you can’t just turn the other way. That’s what Lili Furió tells me. She is a disobediant daughter. Lesbian, activist, tango dancer, Lili was always my mother’s best friend, along with María Marta. The three daughters of perpetrators. Three friends from the time they were teenager. The only one who decided to transform herself into a human rights activist is Lili. She is like a godmother to me for those topics I can’t talk about to anyone else. When I feel ready, she invites me to meetings. I don’t go.

March 24, 2022, or maybe it wasn’t that date at all. I’m at the home of my friend Lucía Vela. Her mother was kidnapped and tortured, enduring electric shock, when she was an adolescent. We cried together, we hugged each other, I heard her talk about her film, about the exile of her mother and aunt. Her aunt decided never to return to Argentina. She was also tortured. Her mother returned. She recently testified at the truth trials.

I’m in my new house, far from Buenos Aires, in Boston. I dream about a woman with short hair who runs and runs; she’s being followed. They find her; they torture her. They immerse her in wáter—the submarine. They pull out her nails. I wake up shivering and in anguish. I had this dream several more times. I keep dreaming about the woman with short hair, she runs, she is afraid. She runs through a factory. I try to find out who the disappeared women prisoners were that my grandfather killed or kidnapped. I don’t see them. The dreams torment me. I begin to be afraid of going to sleep. Roxy says that I should write a letter to my grandfather, one to my mother and one to the woman with short hair. I write my grandfather that I do not pardon him, that I hate him, that he hurt me and I can only imagine how many people whose lives he destroyed. He totally fucked them up. I say that I loved him when he was my good grandfather, but that man doesn’t exist any more. I write to my mom, that I don’t understand how she left me in the care of such a monster. I ask for forgiveness from the woman with short hair for what my family did to her. I burn the three letters. Some days later, I dream again with her, she kisses my forehead. I never see her again.

One day, my grandmother gives me the plaques with military insignias she has kept. Choose the ones you like, she invites me. She had them hanging on the wall before. I don’t know what to do. I didn’t know what to say to her. I take some and toss them into the garbage on my way out. After my grandfather’s death, she also gave me all his military dress uniforms. I have no idea where they are. I don’t want to know either.

It’s after one of the history classes, and this time, the surviver “El Mono” came back. I have a lump in my throat. I want to cry. It is the first time in my life I meet a person in voice and body who was arrested and a direct victim of state terrorism. I asked myself how many more there are. I say that I need to tell him something and explain that my grandfather was a perpetrator. With much shame, tears in my eyes, I cannot explain who this man was because I do not not know. Every time I want to learn, I forget. It is as my mind does not want to recall the horror. He says it doesn’t matter; he hugs me; we drink a coffee in a nearby bakery. The next time I see him, he gives me a book on the history of the People’s Revolutonaty Army Party. That year, a few months earlier, Orlando Oscar Dopazo had died in the Military Hospital. He had a heart attack the moment he saw me. He clutched my hand and broke down.

Orlando Oscar Dopazo in a Military Demostration. Personal Archive. No Date.

I remember. When I was 19 or 21 years old, I lost my wallet. A young man called me; he had found it. I’m studying anthropology. I check and find everything is in the wallet, and then I freeze up when I realize that a Military Circle carnet is among my documents. I’m a lifetime member as my grandfather’s granddaughter. I never thought about it before because I hadn’t gone in ages; I never liked it. My family does go, my former Commuist party dad and my mom use the swimming pool and organize barbecues there. One of my fears has become real, that someone will discover my secret. The next day I call the military club; I renounce my membership a few days later; I just have to go in person to the headquarters in San Martín and say I no longer want to be a member. I do so. I am still the only person in my family to have done so.

I’m at a family dinner with my grandparents. They remember a corporal who sometimes went to get my mom at school because there was an armed confrontation. I hear that term, “armed confrontation” many times at the dinner table. Now that I’m almost 34, I understand that it means state terrorism. I ask myself how much my mother knew. One day, recently, I ask her directly what she knew. She cries. She says to me: you have no idea what it is like to have to assume responsibility for your grandfather’s monstruosities. She says little. There are sorrows that don’t have words.

I remember. I’m eight years old. My grandfather attends a school event because my parents can’t go. Someone says to me something like, you’re the last Dopazo. If you have kids, they aren’t going to carry that name. I ask my father about this comment and he tells me that’s why I have two last names, García Dopazo. That was important to him. I now realize that I have the possibility of being the last in the line. I am not going to have kids. May that blood end right here.

Nieta de Un Represor

Ligando con el Pasado

Por Natalia García Dopazo

Me acuerdo estar en el patio del colegio. El día anterior mi abuelo había sido detenido. No se decía nada. No entendía. Quería decírselo a alguien pero sabía que nadie iba a entender qué estaba diciendo. En esa escuela en 2002 no nos daban historia argentina contemporánea. No habíamos hablado de los golpes de estado ni las dictaduras, no sabíamos nada. Yo no sabía quién era mi abuelo pero sabía que no podía decir que los fines de semana iba al Club Circulo Militar en Olivos, Provincia de Buenos Aires. Sabía que no podía decir eso en la escuela. Decía el club, decía que no me acordaba el nombre.

Me acuerdo. Tengo 7 años, por ahí menos, mi abuelo aparece en la cocina de su casa. Me dice, como siempre, que mire el bolsillo de su camisa. Me trajo figuritas. Siempre tiene figuritas. Si no me lleva hasta la librería y me deja que elija unos stickers o unos papeles de carta. Mi lugar favorito en el mundo son las librerías. Colecciono stickers como si valieran oro. Es mi tesoro más preciado. Mi abuelo siempre me hace regalitos.

Natalia Dopazo y Orlando Oscar Dopazo. Archivos Personales. 1994

Me acuerdo. Tengo 20 años, soy profesora suplente de Historia Latinoamericana Contemporánea en una escuela industrial privada. Estamos en el programa de verdad y memoria que lleva adelante el Estado Nacional. El primer día que tengo que hacer la suplencia me encuentro con una actividad programada. Aparecen varias personas, entre ellas El Mono. Vamos al Centro de Detenciones El Vesubio. Vamos debajo de la autopista. Otro día vamos a la ex- ESMA o Ex- Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada, el Centros Clandestinos de Tortura y Detención más emblemático del país, por donde pasaron unas 5.000 personas. El Mono se presenta, cuenta su historia, militaba en el Partido Revolucionario Argentino (PCR), a su mujer la asesinaron en los vuelos de la muerte, donde arrojaban para su desaparición a personas vivas en el Río de la Plata, estaba embarazada.

Llevo a distintos estudiantes de la escuela a la ex-ESMA. Es Octubre, hace calor, voy,. Nos toca ir al Casino de Oficiales. Se me cierra la garganta. Recuerdo la voz de mi abuela contandome sobre sus fiestas en el Casino de Oficiales de Córdoba o Mendoza, dónde habrá sido. No es este casino. Me acuerdo de las fotos que vi de ellos ahí. Me empiezo a dar cuenta que es el mismo tipo de lugar. En el Casino de Oficiales de la ex- ESMA funcionaba una parte del centro clandestino, nos muestran una sala de revelado de fotografía o una imprenta.

Sector “Capucha”, ubicado en el segundo piso del ex Casino de Oficiales del antiguo centro clandestino de detención de la Escuela de Mecánica de la Armada (actual Espacio Memoria y Derechos Humanos), en Buenos Aires, Argentina.

Estoy en el centro de detención clandestina de la calle Humberto Primo, vamos a otra visita con estudiantes, acá estuvo la periodista Miriam Lewis. Nos muestran la terraza. A ella la dejaban salir de vez en cuando. Vemos el toldo verde y blanco que permitió que ella reconociera el lugar. Vemos también todos los edificios que están allí, imaginando todos los ojos que podrían haber visto este lugar.

Me acuerdo, Es verano, vacaciones de la escuela. Después de almorzar tengo que dormir la siesta. Yo me acuesto en un catre al lado de la cama de mis abuelos. Bajan las persianas. Mi abuela me cuenta el cuento del gallito pelón o del yacaré. A veces cuando mi abuela trabaja, le toca a él. Siempre me habla del ternero Pombo y su mamá.

Mi abuelo fumaba. Murió de cáncer de colon. Un cáncer que nunca dijo que tenía. Mi abuelo fumó toda su vida, pero durante unos años había dejado, cuando era jóven. Me contó que después de ese impass volvió a ser adicto porque se le murió un soldado sobre una camilla después de un enfrentamiento armado.

Me acuerdo. Abro el placard de mi abuelo. Todas las tardes, antes de que mis papás pasen para volver a casa, me va a buscar a la escuela en un Ford Falcon color salmón, este es especial porque tiene caja de cambios de cinco velocidades que está adaptada. Así lo tuvo siempre, como nuevo. Abro el placard. Encuentro dos armas en el placard. No las toco. Armas viejas. Se lo cuento a mi mamá. Después supe que las vendieron. Mi abuela me dijo que Dios podía saber todo lo que yo hacía y pensaba. Y que después se lo contaba a ella.

Vista de la planta de Ford Motor Argentina en General Pacheco, Septiembre de 1982.

Es año nuevo, debe ser 1996, mi hermana es una bebita, estamos en la quinta que nos presta un amigo de mis padres en La Reja, Moreno. Vamos a ver cómo mi papá prende unos fuegos artificiales. Estamos mi abuelo y yo sentados en unas silletas, alejados, mirando las estrellas, esperando que empiece el show casero. Creo que le pregunto de qué trabajaba antes, me dice: luchaba contra la subversión.

Me acuerdo. Tengo 12 años, como todas las tardes, o muchas, lo paso en lo de mi abuela. Se separaron, estuvieron viviendo en casas distintas hasta la detención de mi abuelo. Allí ella salió de garante y acepta que él viva con ella para que no vaya a la cárcel común. De esto me voy a enterar años después. Por un tiempo no nos vimos. Mi mamá no le quiere hablar pero con los años retomamos algún tipo de vínculo. Vivimos todos en el mismo edificio, ellos en el 1ero, nosotros en el 4to. Mi abuelo me pide que le transcriba un papel a mano y lo pase a la computadora. Él no la sabe usar. Me explica que es porque en el juicio que tiene lo acusan de algo que no hizo. Que nadie entiende nada, recuerdo que dice: no entienden el organigrama.

Él no mató a nadie. Él no mató a nadie. Algo que se repite cada cierto tiempo. No es como el represor Paulino Furió, ese si que es jodido, ese tipo es un violento, le pegaba a sus hijos. Tu abuelo es una persona ejemplar. Mi papá, ex militante del Partido Comunista me dice: lo que pasa es que él se le puso de contra a [General Luciano] Menendez, tu abuelo no quiso meterse en unos chanchullos y por eso lo echan antes, en 1978 lo mandan a Buenos Aires. Años después, me va a confesar que él me decía esas cosas para que yo no me preocupara tanto.

Menendez fue a visitar a mi abuelo, Orlando Oscar Dopazo, al Hospital Militar de la Ciudad de Buenos Aires cuando está internado por un estudio, ya hace tiempo vive en arresto domiciliario esperando los juicios. Según me cuenta mi abuela, se acercó a la habitación y mi abuelo se hizo el dormido, no lo quiso ver.

Es la pandemia, por vez número mil, vuelvo a intentar reconstruir quién es Orlando Oscar Dopazo, la persona sobre la cual periodista Horacio Verbitsky menciona en una contratapa de Página 12 en 2004. Parece que mi abuelo estuvo en una matanza en Córdoba. Intento ir a los buscadores de juicios de lesa humanidad, pongo su apellido, sé que él se murió antes de la sentencia de uno de los juicios. Cuántos casos son, 3, 4? Cuál es la diferencia entre las causas. Está en la mega causa de La Perla, el centro de detenciones clandestino cerca de Cordobá? Eso me lo dijo mi novio de aquella época cuando no quiso asistir a una cena familiar. Fue responsable del secuestro del periodista Paco Urondo? Cuál era su rango? Coronel? Teniente Coronel? Sé que estudió en la Escuela de Guerra. Que venía de una familia humilde de Entre Ríos, que quiso ir ahí desde chico. Que a la Escuela de Guerra no entran todos. Que él era muy inteligente. Según mi papá, era una persona con pocas luces. Abro el buscador y por primera vez encuentro un documento elaborado por la Secretaría de Derechos Humanos de La Nación Argentina que habla sobre los organigramas. Es un PDF. CNTRL+F. Dopazo. Aparece el término COT en 1976 en la División de Inteligencia G2.

Cuando mirás al monstruo a la cara no podés hacerte más la boluda. Eso me lo dice Lili Furió. Ella es una hija desobediente. Lesbiana, activista, tanguera, Lili siempre fue la mejor amiga de mi mamá junto con María Marta. Las tres hijas de represores. Las tres amigas desde la adolescencia. La única que decidió convertirse en militante por los derechos humanos es Lili. Es como una madrina para esos temas que no podés hablar con nadie más. Cuando esté lista me invita a las reuniones. No voy.

24 de Marzo de 2022, o tal vez no es esa fecha, pero estoy en la casa de mi amiga Lucía Vela. Su mamá fue secuestrada y torturada, picaneada cuando era una adolescente. Lloramos juntas, nos abrazamos, la escucho hablar sobre el guión que escribe, sobre el exilio de su mamá y su tía. Su tía decidió no volver. También la torturaron. Su mamá si volvió. Hace poco declaró en un juicio de la verdad.

Estoy en mi casa nueva, lejos de Buenos Aires, en Boston. Sueño con una mujer de pelo corto que corre, la persiguen. La encuentran, la torturan. Le hacen el submarino. Le sacan las uñas. Me despierto con la sangre helada. Sueño varias veces más. Sigo soñando con la mujer de pelo corto, corre, tiene miedo. Corre por una fábrica. Trato de buscar quiénes pueden ser las mujeres detenidas desaparecidas que mi abuelo mató o secuestró. No la veo. Me atormentan los sueños. Empiezo a tener miedo de dormir. Mi médica, Roxy, me dice que le escriba una carta a mi abuelo, una a mi mamá y una a la mujer de pelo corto. A mi abuelo le escribo que no lo perdono, que lo odio, que me lastimó y que ni me puedo imaginar a cuántas personas le cagó la vida. Las hizo mierda. Le digo que lo quise cuando era mi abuelo bueno pero eso ya no existe más. Le escribo a mi mamá, que no entiendo cómo me dejó al cuidado de semejante monstruo. A la mujer de pelo corto le pido perdón por lo que le hizo mi familia. Quemo las tres cartas. A los días vuelvo a soñar con ella, esta vez me dice bendiciones, me da un beso en la frente. No la vuelvo a ver más.

Un día mi abuela me regala todos los platos con insignias militares que tiene guardados. Elegite los que te gusten me dice. Antes los tenía colgados en la pared. No sé qué hacer. No sé qué decirle. Agarro algunos, a la salida los tiro a la basura. Después de la muerte de mi abuelo también me regala todos sus trajes de regalia. No tengo idea dónde están. Tampoco quiero saberlo.

Estoy después de una de las clases de historia, esta vez volvió “El Mono”. Yo tengo un nudo en la garganta. No sé qué hacer, sólo quiero llorar. Es la primera vez en mi vida me veo a una persona con cuerpo y voz que estuvo detenida y fue víctima directa del Terrorismo de Estado. Me pregunto cuántos como él hay. Le digo que necesito contarle algo y le explico que mi abuelo fue represor. Con mucha vergüenza, lágrimas en los ojos, no puedo ni explicar quién fue porque no lo sé. Cada vez que quiero aprenderlo me lo olvido. Es como si mi mente quisiera que no recuerde ese horror. Me dice que no pasa nada, me da un abrazo, nos tomamos un café en la panadería a una cuadra de la escuela. La próxima vez que me ve me da un libro sobre la historia del partido. Ese año, unos meses antes, había muerto Orlando Oscar Dopazo en el Hospital Militar. Tuvo un paro cardíaco en el momento en que me vio. Me agarró la mano y se descompuso.

Orlando Oscar Dopazo en una Demonstación Militar. Archivos Personales. Sin Fecha.

Me acuerdo. Tengo 19 o 21 años, perdí la billetera. Me llama un chico, la encontró. Estoy estudiando Antropología. Me cuenta que está todo, pero entre mis documentos hay un carnet del Círculo Militar. Se me hiela la sangre. Soy socia vitalicia por ser la nieta de mi abuelo. Nunca lo había pensado antes, hace mucho que no voy. No me gusta ir, nunca me gustó. Mi familia si va, mi viejo ex militante del PC y mi mamá usan la pileta, organizan asados. Yo hace tiempo que dejé de ir. Me doy cuenta que el peor de mis miedos se hace realidad, alguien sabe mi secreto. Al día siguiente llamo al círculo, me desasocio a los días, sólo tengo que ir en persona a la sede San Martín y decir que no quiero ser más socia. Lo hago. Sigo siendo la única persona de mi familia que hizo eso.

Cena familiar con mis abuelos. Se acuerdan de un cabo que a veces fue a buscar a mi mamá a la escuela porque había un enfrentamiento armado. Escuché muchas veces en la mesa familiar el término enfrentamiento armado. A mis casi 34 años entendí que estaban hablando de terrorismo de estado. Me pregunto cuánto sabe mi mamá. Un día le pregunto, hace poco, qué sabía ella. Llora. Me dice: vos no te tenés que hacer cargo de las monstruosidades de tu abuelo. Habla poco. Hay dolores que no tienen palabras.

Me acuerdo. Tengo ocho años. Mi abuelo va a un acto escolar porque mis padres no pueden ir. Me dice algo como, vos sos la última Dopazo. Ya no van a quedar más porque si tenés hijos no les vas a pasar ese apellido. Le pregunto a mi papá después y me explica que por eso tengo los dos apellidos, García Dopazo. Porque para él era importante. Ahora me doy cuenta que tengo la posibilidad de cortar el linaje Dopazo. Me viene una certeza y sé que no voy a tener hijos. Que esta sangre se termina acá.

Natalia García Dopazo studied anthropology at the National University of Buenos Aires. For more than 10 years she has been working for the right to the city as a feminist urban planner in public policy. She was a Harvard Graduate School of Design Loeb Fellow 2002-2023 and Harvard Weatherhead Research Fellow 2023.

Natalia García Dopazo estudió antropología en la Universidad Nacional de Buenos Aires. Desde hace más de 10 años trabaja por el derecho a la ciudad como planificadora urbana feminista en política pública. Fue Harvard Graduate School of Design Loeb Fellow 2002-2023 y Harvard Weatherhead Research Fellow 2023.

Related Articles

Haiti: A Gangster’s Paradise

Haiti is in the news. In recent weeks, gangs have coordinated violent actions, taken to the streets and liberated thousands of inmates to spread chaos and solidify their control of the Port-au-Prince capital.

Crime and Punishment in the Americas

As 2024 ushered in, newly-elected Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa issued a state of emergency in his country, citing a wave of gang violence spurred by the prison escape of a local criminal leader with ties to Mexico’s ruthless Sinaloa Cartel.

Women CEOs in Latin America: Overcoming obstacles, navigating through challenges

I first arrived in Latin America in 1997, and since then, I’ve been involved in education and the development of leadership and governance issues in the region. During these 27 years—12 of them from Spain—I have had the opportunity to interact with leaders from the region, the private and public sectors, multinationals and small and medium-sized enterprises, and various industries.