Hidden Treasures of the Antilles

The Antilles and treasures… the Antilles and treasures….these are perhaps the most frequent associations everyone makes with the group of islands in the Caribbean Sea, whether due to the genius of Robert Louis Stevenson or the charisma of Jack Sparrow or, really, because of a certain historic truth glorified by film and literature about pirates and buccaneers, who swarmed the Caribbean attracted by riches plundered from the supposed “New World.”

The Antilles are, indeed, a place of exquisite treasures, some well-known and recognized, but others (many) are still hidden to the eyes of humanity. I’m not referring to doubloons and pearls here, but to marvelous, unequaled nature, particularly its “living nature” or biodiversity.

Even since scientists began to classify and study biological diversity in the Antilles, they became aware of its uniqueness and richness. Botanists were astonished by its flora and several zoological icons enchanted scholars and naturalists. The world learned about the existence, just to give you a few examples, of giant insect-eating mammals (Solenodon cubanus and Solenodon paradoxus), teeny birds (Mellisuga helenae), frogs (Eleutherodactylus limbatus), bats (Nyctiellus lepidus), charismatic iguanas (Cyclura nubila), endemic crocodiles (Crocodylus rhombifer), fantastic lizards (Anolis spp.) and extraordinary blind fish who live in caves (Lucifuga dentata and Lucifuga subterranea), all of whom inhabit these beautiful islands of sun and beaches.

Examples of the marvelous vertebrate fauna of the Antilles: A: Cuban solenodon (Solenodon cubanus); B: butterfly bat (Nyctiellus lepidus); C: bee hummingbird (Mellisuga helenae). Photo credits, A: Lázaro Echenique; B: Carlos A. Mancina; C: Aslam Ibrahim Castellón Maure.

However, in more than two-and-a half centuries of zoological nomenclature, the catalog of the terrestrial fauna of the Antilles we’ve managed to name is very unbalanced in favor of the diversity of “vertebrate” animals in detriment to the much more numerous “invertebrates.” This is a worldwide phenomenon known in some scientific circles as the “bias of the megafauna.” In the Antilles, few exceptions escape this panorama among the terrestrial arthropods, those invertebrate animals with an exoskeleton of chitin and a segmented body. Among these exceptions are daytime butterflies (Rhopalocera), some groups of beetles (for example, Cerambycidae) and scorpions. The degree of inventory of other groups of arthropods varies from island to island; the great majority are scarcely registered or totally unknown. Indeed, if one thing is completely certain, it is that as you walk, enjoy, explore or rest in the exuberant nature of any of the islands of the Antilles, around you are dozens or even hundreds of new species of arthropods completely unknown to science. A true hidden treasure!

And when we talk about hidden animals, we are referring not only to the fact that science has not yet categorized them, but also to the fact that there are literally many groups of arthropods who live in the dry leaves of the forest floors, the inside of fallen trunks, beneath those trees and under rocks, in cracks and all sorts of underground habitats, including deep within caves formed in the abundant carbonated rocks of the Antillean archipelago. That’s another reason these groups of arthropods are also unknown. It’s not easy to catch them, and biologists often have to spend hours in these habitats scrutinizing cryptic species, sorting through dry leaves to later place them in funnels or on white trays and extract the specimens. Or they might have to learn techniques of speleology—cave study and exploration—to pluck these treasures from the belly of the earth.

Above, from left to right, sorting through dry leaves with a sifter, together with the recently late and renowned arachnology curator of the American Museum of Natural History, Norman Platnick, concentrating on the leaf pile on a tray, assembling the portable Berlese funnels for the passive extraction of the arthropods present in the leaf pile. Below: Harvard Professor Gonzalo Giribet and George Washington University Professor Gustavo Hormiga actively capturing the arthropods from the leaf pile with the aid of a white tray, University of São Paulo Ph.D. student Flávia Pellegatti Franco collecting arthropods from the depths of a cave.

But before you think that my words about hidden treasures are pure romantic fantasies of a fanatic nature lover, let me give you some examples of a zoological group to which I have dedicated the last 30 years of my life: the Opiliones (commonly known as “Harvestmen” or “Daddy Long Legs”). This fascinating group of arthropods is related to spiders and scorpions, but it is an independent group. Thus, we have spiders, scorpions, and opiliones, among other groups, which are included in the most inclusive category called the Arachnid Class.

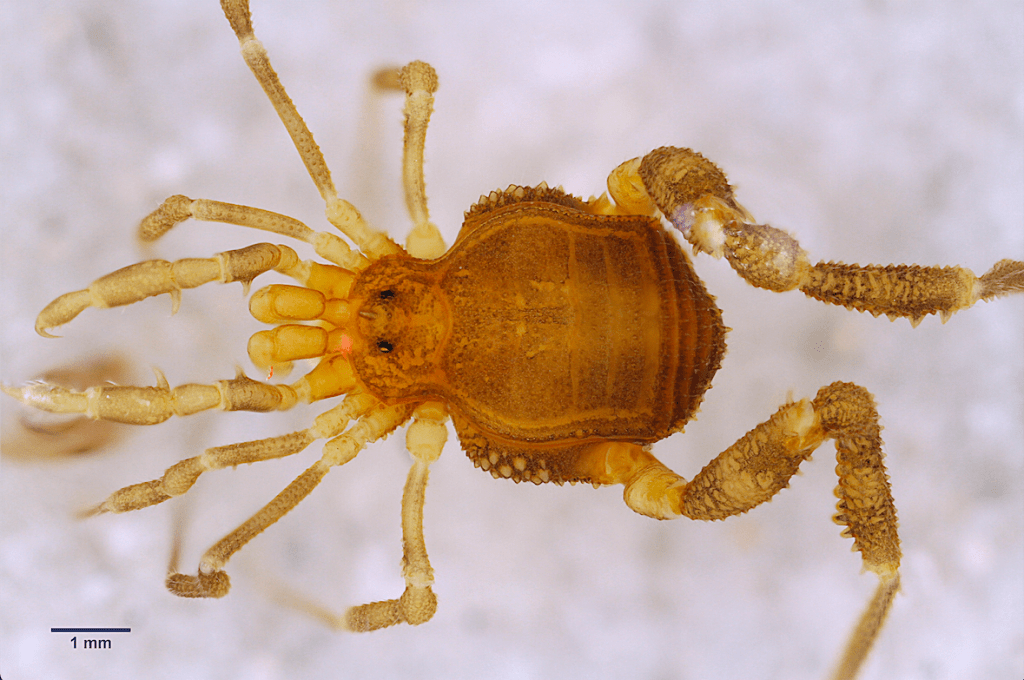

Well, getting back to opilionids, the Antilles and its hidden treasure, I’m going to tell you a bit about the daddy long legs of the Neoscotolemon genus. But my history with them does not begin here and does not start with this name. It begins at the beginning of the 90s, when I was a young and curious biology student in Cuba. Together with my classmates, we visited several caves near the town of “La Salud” south of Havana. There, in a cave named Inzunza, we collected several opilionids that we tried to identify when we got back to the classroom. It’s impossible to convey the fascination and astonishment I felt when I observed these opiliones for the first time under a stereo-microscope! What an incredible animal and what powerful front appendages! I later learned the technical name, pedipalps, but I never lost the astonishment.

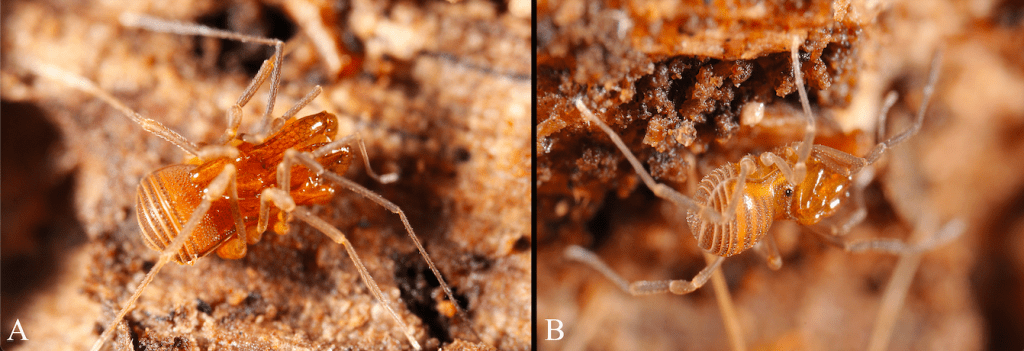

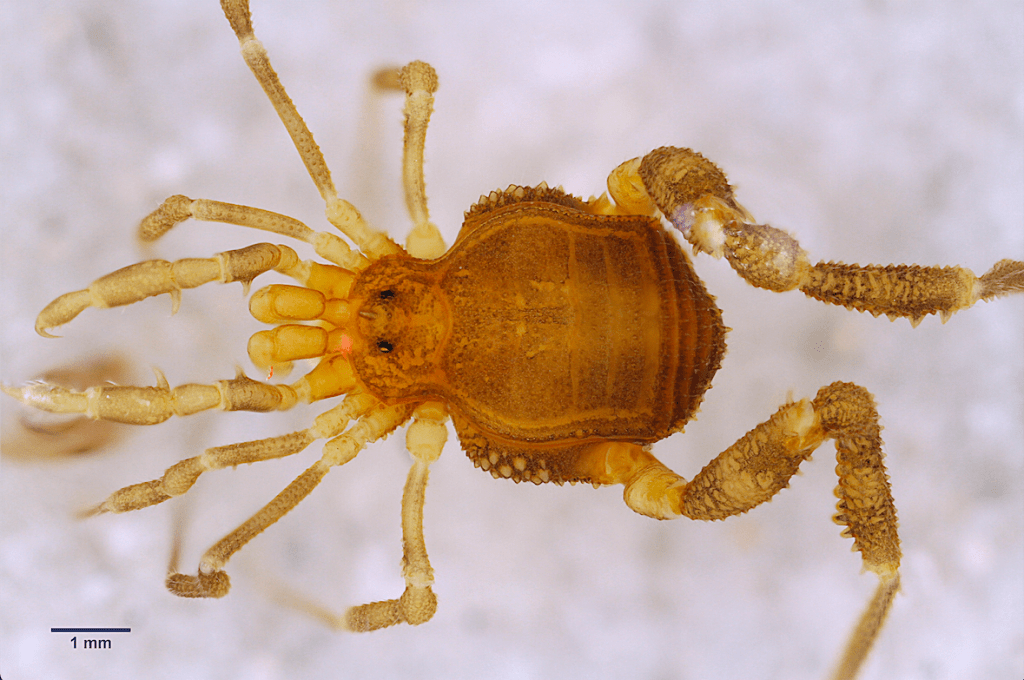

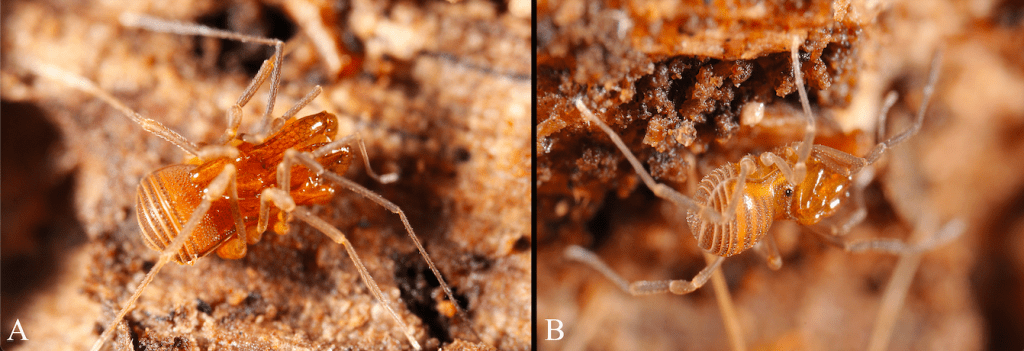

Two new species of Neoscotolemon I found under the same wet tree trunk in la Sierra de la Guira, Pinar del Río, Cuba. A: 2.5 mm body specimen. B: 1.5 mm specimen.

At that moment, I felt the overwhelming necessity to know what it was, to know the name of this fantastic species….at that moment my “gene of taxonomy” had expressed itself compulsively. And at that very moment, the tribulations inherent in the life of a taxonomist began and have not left me to this very day. Effectively, although you might not believe it, the often vilified field of taxonomy is perhaps one of the most difficult, integral and fascinating specialities that a biologist can have. But let’s not stray from our route; in another opportunity, we’ll be able to discuss taxonomy, taxonomists and the taxonomic impediment, all of which are stimulating topics.

Returning to our Cuban opilionid, after a lot of research, visiting libraries and seeking advice, above all from my dear Professor Luis F. de Armas, I came to the conclusion that it was one of the species that had been collected in Cuba by the renowned Spanish docent, entomologist and politician Cándido Luis Bolívar y Pieltáin in 1943. The specimens collected by Bolívar were studied by the U.S. spider experts Clarence and Marie Goodnight in 1945 who described one genus and two species: the genus Rula and the species Rula cotilla and Rula bolivari. I was intrigued because I believed I had collected, for the second time in history, specimens of Rula cotilla for the first time in 45 years!

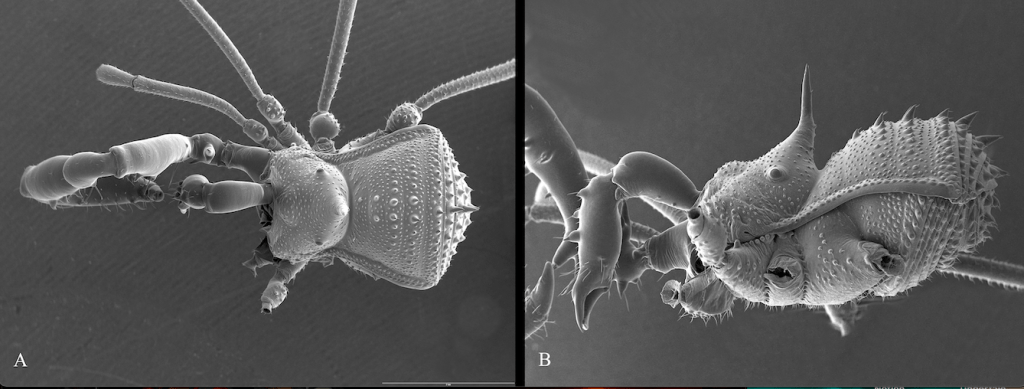

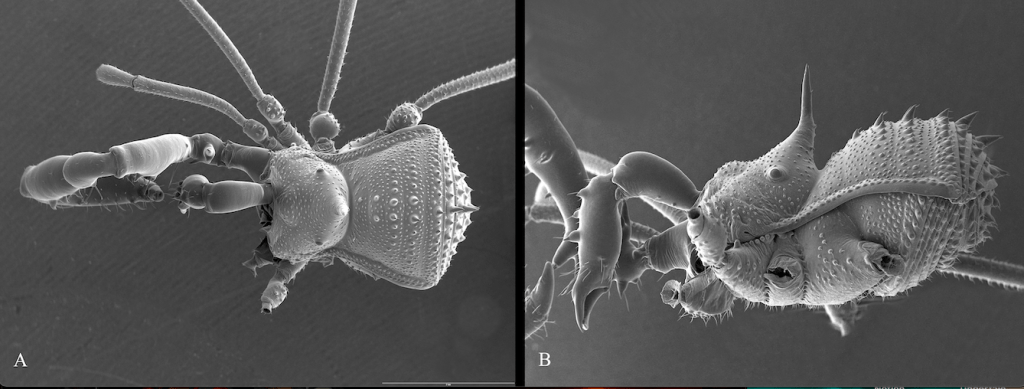

Micro-photographs of Rula bolivari taken with an electronic microscope with an electronic scanner. A: dorsal view. B: side view. The appendages on the left side were removed to get a better view of the morphological characteristics of the body from a side view. Micro-photographs Daniel N. Proud.

However, continuing with my bibliographic investigation, I learned that years later, the same authors determined that both species of Rula were, in fact, one species called Stygnomma spinifera (described originally by Alpheus Spring Packard, Jr. in 1888, under the name Phalangodes spinifera) that was distributed throughout Florida, as well as in Cuba and also the Yucatan Peninsula. My illusions were crushed! My beautiful Cuban opilionid was not so rare after all. I was far from knowing that this history had hardly begun.

In 1993, I had the opportunity to train with Dr. Emilio Maury, specialist in Opiliones at the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences Bernardino Rivadavia, who was extraordinarily kind in asking on loan for the types of species described by Packard and the Goodnight couple and… Surprise! What had been thought to be Stygnomma spinifera were actually four distinct species. That is, Rula cotilla and Rula bolivari were valid and distinct from each other and Stygnomma spinifera described from Florida and Yucatán were also two distinct species. My happiness didn’t last for very long, because soon other doubts arose, such as what kind of harvestmen really belonged to the genus Stygnomma. The answer came only seven years later when I visited the Senckenberg Natural History Museum in Frankfurt, Germany, and could ascertain that the true Stygnomma species lived exclusively in South America and were very different from Rula. That same year, I visited the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology and discovered that the two Rula species were very similar to two other Cuban species: Neoscotolemon pictipes and Vlachiolus vojtechi. The first, Neoscotolemon pictipes, had been described (under the genus Scotolemon) by Nathan Banks, a U.S. spider expert in 1908, and the second, Vlachiolus vojtechi, by Vladimír Šilhavý, a Czech doctor and specialist in Opiliones in 1979.

More than a decade since that young biology student (me) collected an opilionid in a Cuban cave, I was close to discovering its classification! To correctly name it, I had to pick between three genera: Rula, Vlachiolus and Neoscotolemon. To resolve these questions, there’s a “book of laws” called the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature that regulates the system of naming in that field. In one of its articles, the code establishes “The Principle of Priority”, that is, the valid name is the first one described (= the valid name of a taxon is the oldest available name applied to it). Since Neoscotolemon was described in 1912, Rula in 1945, and Vlachiolus in 1979, this first genus name has priority over the others. Therefore, in conclusion, all of these species turned out to be Neoscotolemon! Yikes! I hope you readers have been able to follow this tortuous labyrinth! I think this example from real life, extending for more than a decade, illustrates perfectly how being a taxonomist is not an easy task and how we need to have qualities of Sherlock Holmes and lawyers mixed into one.

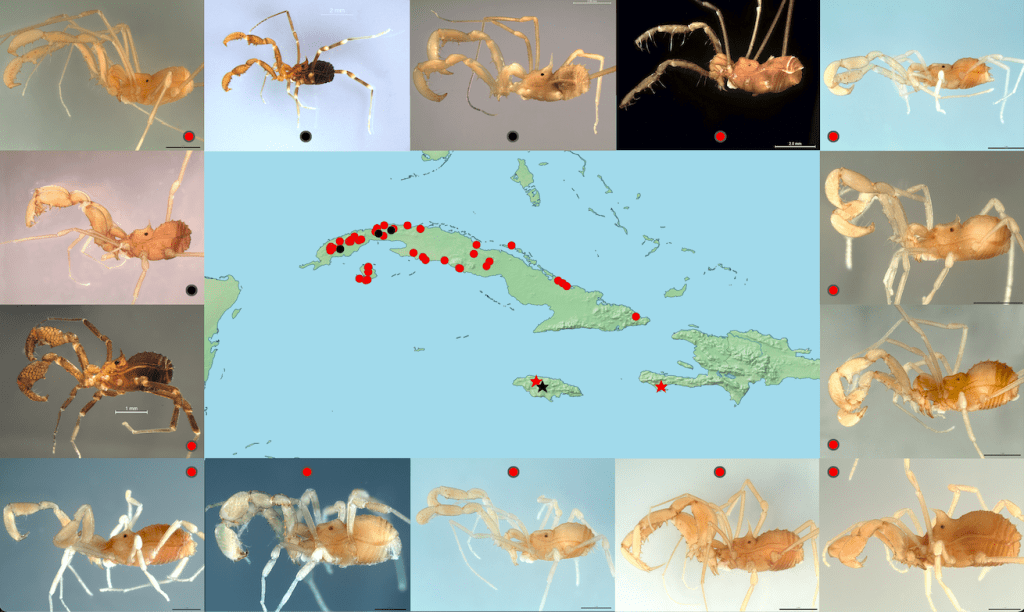

Finally I knew that what we had in Cuba were four species of Neoscotolemon and I now knew how to recognize them. From that moment on, I began to collect them all over the island and to revise the rich collection deposited in the Cuban Institute of Ecology and Systematics. New species of Neoscotolemon began to appear all over the place! The high species richness, the low distributional range of each one (restricted to a few km squares), and the variety of morphological characteristics were notable. The greatest diversity was found in the western part of the island, but specimens also appeared in the center and the eastern part of Cuba, on the Isle of Youth and in the Sabana-Camaguey Keys. One, two, three… 50 new species on an island where, for more than a century, only four had been identified. They had been just there, right in front of our very noses…better said, below our noses and some literally hidden below the earth adapted to live exclusively in caves, waiting to be detected. All together, a gigantic treasure.

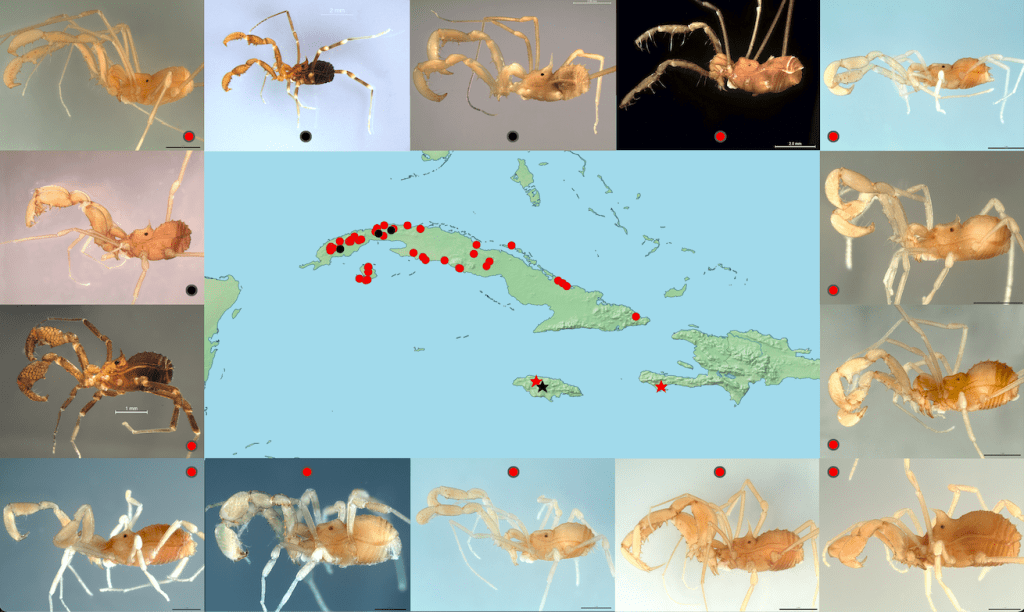

The circles on the map and the photographs of specimens show the distribution and external morphology through a side view of Nescotolemon species. The black circles represent species known today and the red circles indicate species that are new to science that are in the process of being officially described and named. The black star represents where the cave-dwelling Stygnomma fiskei is found, while the red stars show related epigeous (those found in superficial environments) species that science still has to describe. Photos: Vanesa Mamani and Daniel N. Proud.

Recently, and thanks in part to collection efforts of the CarBio project, headed up by Ingi Agnarsson of the University of Iceland and Greta Binford of Lewis and Clark, we have been able to carry out the first phylogenetic (hypothesis of evolutionary relationships among biological entities) analysis of the Neoscotolemon species. We keep on being surprised. Now we know that the group began to diversify in Cuba some 34 million years ago and that the species in Florida and the Yucatan are the results of recent dispersions from Cuba to both peninsulas. We also know that the closer related harvestmen of Neoscotolemon are a cave-dwelling species in Jamaica, Stygnomma fiskei—described by the Spanish opilionid expert María Rambla Castells in 1969—and two new species to be described from Jamaica and Haiti.

As you can see, the number of officially recognized species is miniscule and very many of those discovered still have to be categorized. It took a long time to forge the bases to a reliable identification, but it’s now being established and we are beginning to move forward. Together with colleagues and students, we are hard at work so that soon, all of these new species will officially enter into the catalog of Antillean biodiversity.

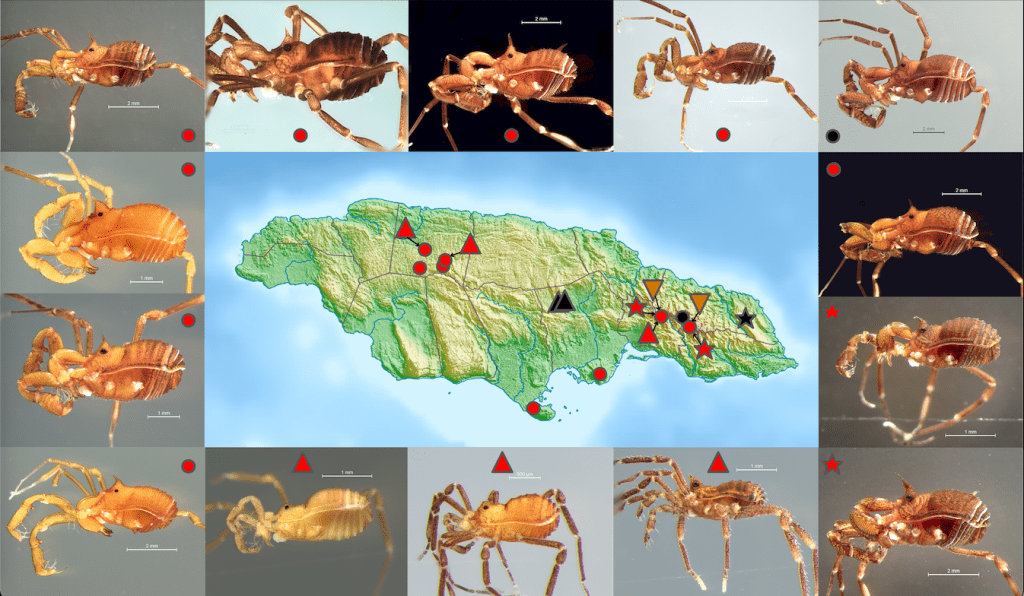

Let us now write about the opilionids of the Island of Reggae, Jamaica, and learn about its hidden treasures. For example, let’s look at the species of the genera Akdalima, Reventula and Ethobunus. Two of the Opiliones experts cited above were responsible for describing the Jamaican species in these categories. María Rambla worked with material collected in 1968 by Stewart B. Peck of Carleton University and Alan Fiske of UCLA, during a quick six-day collection visit to seven caves in the western half of the island. In 1969, Rambla published the description of Cynortina pecki and Cynortina goodnighti, which are currently in the genus Ethobunus. One of them, Ethobunus pecki, is totally blind (!), it doesn’t have a retina, but also doesn’t have any signs of ocular structure, something called “anophthalmia”. This characteristic, together with other morphological traits such as lack of pigment and lengthening of appendages (legs and pedipalps, two kinds of the cephalothorax appendages) reflect the adaptation process to live exclusively in the cave environment. On the other hand, Ethobunus goodnighti, presents functional eyes (with a retina), pigmented body and short appendages, which makes us think that it is not an exclusively cave-dwelling species and therefore can have populations outside the caves. Vladimír Šilhavý, studying the opiliones in the collections of the Harvard Museum of Comparative Zoology, described the species Akdalima jamaicana, which he placed in the Akdalima genus that he himself had created two years before for a Mexican opilionid from Chiapas. Also, he described the genus and new species Reventula amabilis from the John Crow mountains in Jamaica’s eastern highland region.

More than fifty years after Šilhavý’s description, I had the amazing opportunity to join a scientific expedition to Jamaica organized by the CarBio project. This excursion wasn’t as short as Stewart Peck’s six-day whirlwind, but it wasn’t very long either: 20 days of collecting that allowed us to experience several places throughout the island. However, with only this small effort of obtaining samples, we managed to quadruple the insular diversity known of Akdalima, Reventula and Ethobunus, going from four to 15 species, including a new genus for science.

The Akdalima representatives, with our collection of its eight new species, surprised us by being all native to the island, which made us suspect there were a lot more species to be found in still unsampled areas. We also found out through phylogenetic analysis that Jamaica’s Akdalima was more closely related to the country’s Reventula (with also two new species!) than it was with the “true” Akdalima from Chiapas, Mexico. Now we’ll have to investigate whether the Jamaican species are Reventula or if we have to describe and name a whole new genus… we’re working on it. Three new species of Ethobunus have also been added to the two previously known species on the island. They are extraordinary in their external morphology and genitals and definitely are not related to the “true” Ethobunus from Costa Rica and Panama. Again, the hard work of defining a genus name for those species is in front of us.

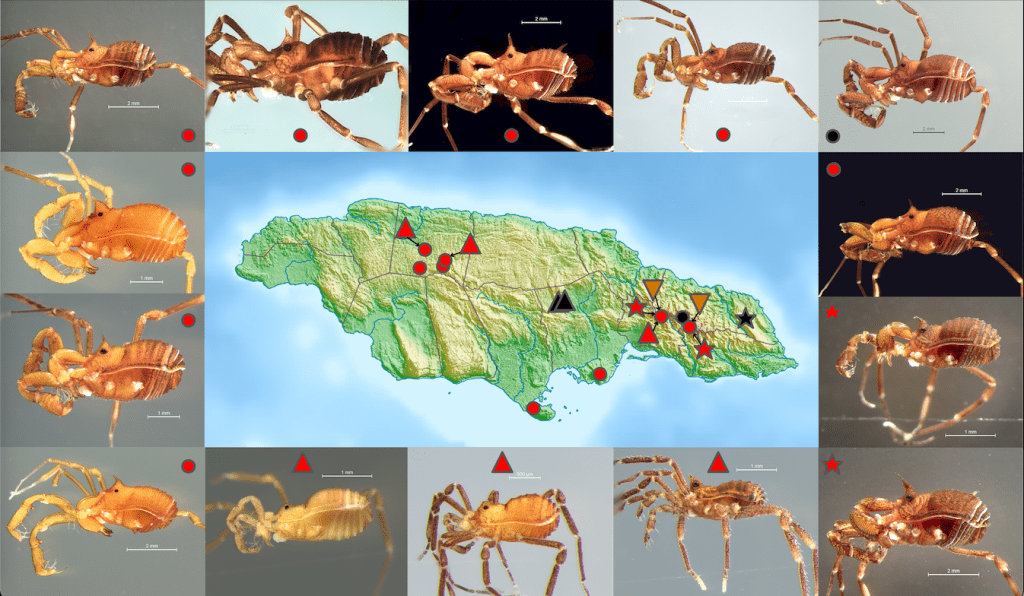

The circles on the map and the photographs show the distribution and external morphology from a lateral view of the Akdalima species in Jamaica. The black circle represents Akdalima jamaicana and the red circles are species new to science in the process of description. The stars show the distribution and external morphology from a lateral view of the Reventula species. The black star represents Reventula amabilis and the red stars correspond to new species. The black triangles Ethobunus pecki and Ethobunus goodnighti and the red ones, three new species. The brown inverted triangles mark where the two new species of the previously unknown genus. Photos: Daniel N. Proud.

Just as in Cuba, the number of unknown species is by far greater than the known ones. What particularly strikes me is that in the case of Jamaica, it only took a short 20-day expedition to gather more than had been done in almost half a century. How much more could we discover with a systematic and extensive sampling, with taxonomic work prioritizing Antillean ground arachnids!

I believe the two examples I’ve given you should be enough to convince you about the enormous unknown biodiversity of the Antilles, but I don’t want to finish without talking about the marvelous island of Hispaniola, made up of the Dominican Republic and Haiti. This is an island of mountains that reach 10,000 feet, home to the most unknown diversity of opilionids in the entire Antilles. Some opilionids have been discovered first through their fossilized species, trapped in the famous Miocene amber deposits, some 15 to 20 million years old, even before their living species. This is precisely the case of the fossil specimen of the Kimula genus, which had been reported by James C. Cokendolpher of Texas Tech University and George O. Poinar, Jr. of Oregon State in 1992. The fossil was the only known Dominican species of opilionid from this genus. That was the case for eight years when, in 2000, I described Kimula cokendolpheri, together with my Cuban colleague and Professor Luis F. de Armas. Until now, Kimula cokendolpheri it’s still the only known living species of this genus on the island. However, (and you’ve probably suspected what I’m going to describe), the collections of the National Museum of Natural History Prof. Eugenio de Jesús Marcano in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, houses more than 50 specimens belonging to several new living species. There are at least six new species of Kimula. I had the opportunity to identify these species virtually and, I hope, in the not-too-distant future, I will have the opportunity to study them.

Opilionid specimen in the collection of the Museum of Natural History Prof. Eugenio de Jesús Marcano in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, corresponds to an unclassified living species of the genus Kimula. Photo: Solanlly Carrero Jiménez.

Let’s go back then to the beginning of our history: the Antilles and treasures… Antilles and treasures….Without a single doubt! An immense richness of hundreds of species that have survived hidden from science in the depths of the forests, mountains and caves. They are treasures of disparate evolutionary and biogeographic lineages; treasures stored in insular museums of biodiversity and form part of one of the most spectacular evolutionary laboratories in the world. The discovery of these treasures is fundamental to help us understand how the product of the beautiful phenomenon of life on our planet lived, lives and will continue to live.

Antillas y Tesoros Escondidos

Por Abel Pérez González

Antillas y tesoros… Antillas y tesoros… es, tal vez, una de las asociaciones más arraigadas en la humanidad, quien sabe si por culpa de la genialidad de Robert Louis Stevenson o el carisma de Jack Sparrow o, realmente, por una cierta verdad histórica ensalzada por el cine y la literatura de corsarios y piratas, los cuales pululaban en el Caribe atraídos por las riquezas extirpadas al supuesto “nuevo mundo”.

Las Antillas son, sí, un lugar de exquisitos tesoros, algunos muy conocidos y reconocidos, pero otros (muchos) permanecen ocultos a los ojos de la humanidad, y no me refiero a doblones y perlas, me refiero a una maravillosa e inigualable naturaleza, y en particular, a su “naturaleza viva” o biodiversidad.

Desde que la ciencia comenzó a inventariar y a estudiar la diversidad biológica de las Antillas, se dio cuenta de su singularidad y riqueza. Los botánicos quedaron estupefactos con su flora y varios íconos zoológicos encantaron a estudiosos y naturalistas. El mundo conoció, por solo citar algunos ejemplos, mamíferos insectívoros gigantes (Solenodon cubanus y Solenodon paradoxus), diminutas aves (Mellisuga helenae), ranas (Eleutherodactylus limbatus) y murciélagos (Nyctiellus lepidus), carismáticas iguanas (Cyclura nubila), cocodrilos endémicos (Crocodylus rhombifer), fantásticas lagartijas (Anolis spp.) y extraordinarios peces ciegos cavernícolas (Lucifuga dentata y Lucifuga subterranea) que habitaban en esas hermosas islas de sol y playas.

Ejemplos de maravillas de la fauna de vertebrados de las Antillas: A: el Almiquí cubano (Solenodon cubanus); B: el murciélago mariposa (Nyctiellus lepidus); C: el Zunzuncito (Mellisuga helenae). Fotos: A: Lázaro Echenique; B: Carlos A. Mancina; C: Aslam Ibrahim Castellón Maure.

Sin embargo, en más de dos siglos y medio de historia de la nomenclatura zoológica, el elenco de la fauna terrestre Antillana que hemos conseguido nombrar muestra un gran desbalance a favor de la diversidad de los animales “vertebrados” en detrimento de los mucho más numerosos “invertebrados”. Este es un fenómeno mundial el cual es conocido en determinados círculos científicos como el “sesgo de la megafauna”. Existen pocas excepciones que escapan a este panorama entre los artrópodos (invertebrados con cuerpo segmentado cubierto por un exoesqueleto quitinoso) terrestres de las Antillas, entre ellas podríamos nombrar a las mariposas diurnas (Rhopalocera), algunos grupos de coleópteros (por ejemplo, Cerambycidae) y los alacranes o escorpiones. Para otros grupos de artrópodos el nivel conocimiento varía entre islas y una gran mayoría son escasamente registrados o totalmente desconocidos. Sí, una cosa es 100% segura, en cuanto usted camina, disfruta, explora o descansa en contacto con la naturaleza de cualquiera de las islas Antillanas, a su alrededor existen decenas o centenas de nuevas especies de artrópodos desconocidos completamente por la ciencia. ¡Un verdadero tesoro escondido!

Y cuando hablamos de escondidos nos referimos no solamente a que la ciencia no los conoce, nos referimos literalmente a muchos grupos de artrópodos que habitan en lugares como la hojarasca de los bosques, el interior de los troncos caídos, debajo de ellos y debajo de piedras, ranuras, grietas y todo tipo de hábitat subterráneos, incluyendo las profundidades de las cuevas que se desarrollan en las abundantes rocas carbonatadas de los archipiélagos antillanos. Por esos motivos estos grupos de artrópodos son también desconocidos. Su captura no es fácil, por el contrario, los biólogos tienen que pasar horas en estos hábitats escudriñando especies cripticas, cerniendo hojarasca para después colocarla en embudos o en bandejas blancas para poder extraer los ejemplares o aprender técnicas de espeleología (ciencia que estudia las cuevas y cavernas) para poder arrancar estos tesoros de las mismísimas entrañas de la tierra.

Arriba, de izquierda a derecha: cerniendo hojarasca con el “sifter”, junto al recientemente fallecido y renombrado curador de la colección aracnológica del Museo Americano de Historia Natural de Nueva York, Norman Platnick, concentrando la hojarasca cernida en una bandeja y armando los embudos Berlese portátiles para la extracción pasiva de los artrópodos presentes en la misma. Abajo: Gonzalo Giribet de la Universidad de Harvard y Gustavo Hormiga de la Universidad de George Washington capturando activamente los artrópodos de hojarasca con el auxilio de una bandeja blanca y por ultimo la alumna de doctorado de la Universidad de São Paulo, Flávia Pellegatti Franco, colectando artrópodos en lo más profundo de una caverna.

Pero antes que crean que mis palabras son puras especulaciones nacidas del romanticismo de un apasionado amante de la naturaleza, permítanme ejemplificar mis dichos con un grupo zoológico al cual he dedicado los últimos 30 años de mi vida: los Opiliones. Este fascinante grupo de artrópodos es pariente de arañas y escorpiones (entre otros) pero al igual que ellos conforma un grupo independiente al cual los zoólogos denominan de “Orden”. Entonces contamos con el Orden de las arañas, de los escorpiones y de los opiliones entre otros que conforman la categoría más inclusiva denominada Clase Arachnida.

Bueno, volviendo a los Opiliones, las Antillas y los tesoros escondidos, les voy a contar sobre los opiliones del género Neoscotolemon. Pero mi historia con ellos no empieza aquí y no empieza con ese nombre. Empieza a inicio de los años 90, cuando era un joven y curioso estudiante de Biología en Cuba. Junto a mis colegas de clase visitamos varias cuevas cerca del poblado La Salud al sur de La Habana. Allí, en una cueva llamada Inzunza, colectamos varios opiliones los cuales intenté identificar una vez de regreso a la Facultad. ¡Es imposible narrar la fascinación y el asombro que sentí al observar por primera vez estos opiliones bajo un estereomicroscopio! ¡Que animal increíble y que apémdices frontales tán poderosos tenía! Más tarde aprendí que estos apéndices son llamados pedipalpos en los arácnidos, pero nunca pude olvidar la primera impresión y asombro al ver los pedipalpos de los opiliones!

Dos nuevas especies de Neoscotolemon que encontré debajo de un mismo tronco húmedo en la Sierra de la Guira, Pinar del Río, Cuba. A: ejemplar de 2,5 mm de cuerpo. B: ejemplar de 1,5 mm de cuerpo.

En ese momento sentí la imperiosa necesidad saber quién era, de saber como se llamaba esta fantástica especie… en ese momento, compulsivamente, se había expresado en mí “el gen del taxónomo”. Y también en ese mismo momento empezaron las tribulaciones inherentes a la vida de un taxónomo, las cuales no me han abandonado hasta el día de hoy. Efectivamente, aunque no lo crean, la tan vilipendiada especialidad de taxónomo es quizás una de las más difíciles, integrales y fascinantes que un biólogo puede tener. Pero, no nos desviemos por ese camino, en otra oportunidad podemos tratar la taxonomía, el taxónomo y el impedimento taxonómico, todos temas interesantes.

Regresando a nuestro opilión cubano, después de mucho buscar, visitar bibliotecas y pedir consejo, sobre todo a mi querido profesor Luis F. de Armas, llegué a la conclusión de que se trataba de una de las especies que había sido colectada en Cuba por el renombrado docente, entomólogo, espeleólogo y político español Cándido Luis Bolívar y Pieltáin en 1943. Los ejemplares colectados por Bolívar fueron estudiados por la pareja de aracnólogos estadounidenses Clarence y Marie Goodnight en 1945 quienes describieron un género y dos especies: Rula cotilla y Rula bolivari. ¡Yo estaba fascinado porque creía haber colectado, por segunda vez en la historia, ejemplares de Rula cotilla al cabo de 45 años!

Microfotografías de Rula bolivari tomadas con un microscopio electrónico de barrido. A: vista dorsal. B: vista lateral. Los apéndices izquierdos fueron removidos para una mejor visualización de las características morfológicas del cuerpo en vista lateral. Micrografías Daniel N. Proud.

Sin embargo, continuando con la investigación bibliográfica, me deparé que años más tarde, los mismos autores dictaminaron que ambas especies de Rula eran, en realidad, una especie llamada Stygnomma spinifera (descrita originalmente por Alpheus Spring Packard, Jr. en 1888, bajo el género Phalangodes) que se distribuía tanto en Florida, como en Cuba y también en la península de Yucatán. ¡Que desilusión! Mi hermoso opilión cubano era una especie ampliamente distribuida. Estaba yo lejos de saber que esta historia apenas comenzaba.

En 1993 tuve la oportunidad de entrenarme con el Dr. Emilio Maury, especialista en opiliones del Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia”, quien tuvo en ese entonces la enorme gentileza de pedir prestado los tipos de las especies descritas por Packard y por los esposos Goodnight y… ¡Sorpresa! ¡Lo que se creía una especie eran en realidad cuatro especies distintas! O sea, Rula cotilla y Rula bolivari eran válidas y diferentes entre sí y los Stygnomma spinifera de Florida y Yucatán también eran dos especies diferentes. La alegría duró poco, pues no conocía quien eran en realidad los Stygnomma ya que el género estaba atado a una especie Colombiana. La respuesta solo vino siete años después cuando visité el Museo Senckenberg de Historia Natural en Fráncfort, Alemania, y pude comprobar que los verdaderos Stygnomma no eran congenéricos con los Rula y ese mismo año visitando el Museo de Zoología Comparada de la Universidad de Harvard, pude descubrir que las especies de Rula eran congenéricas con otras dos especies cubanas denominadas Neoscotolemon pictipes y Vlachiolus vojtechi. La primera había sido descrita (bajo el género Scotolemon) por otro aracnólogo estadounidense llamado Nathan Banks en 1908 y la segunda por el medico checoslovaco y especialista en opiliones, Vladimír Šilhavý, en 1979.

¡Más de una década después que aquel (yo) joven estudiante de biología colectó un opilión en una cueva de Cuba finalmente estaba cerca de descubrir a que género pertenecía! Tenía entonces que escoger un género entre Rula, Vlachiolus y Neoscotolemon. Para dirimir estas cuestiones existe una especie de “libro de leyes” que regula la nomenclatura y que se llama Código Internacional de Nomenclatura Zoológica. En uno de sus artículos este código establece el “Principio de Prioridad”, o sea, prevalece el nombre válido que fue descrito primero. Como teníamos que Rula fue descrito en 1945, Vlachiolus en 1979 y Neoscotolemon en 1912, este último género tenía prioridad de uso sobre los otros. ¡Entonces, concluyendo, todas esas especies deberían ser ubicadas en el género Neoscotolemon! ¡Ufff! ¡Espero hayan podido seguir este tortuoso laberinto! Creo que este ejemplo real, de más de una década, ilustra perfectamente la faceta de Sherlock Holmes y de abogado que debe tener un taxónomo.

Finalmente supe que lo que teníamos en Cuba eran cuatro especies de Neoscotolemon y ya sabía cómo reconocerlas. A partir de ese momento comencé a colectar a lo ancho y largo de la Isla y a revisar la rica colección depositada en el Instituto de Ecología y Sistemática de Cuba. ¡Empezaron a aparecer nuevas especies de Neoscotolemon por todos lados! Era notable la diversidad, el endemismo y la variedad de características morfológicas. La mayor diversidad se concentró en la región occidental de la Isla, pero aparecieron tanto en el centro como en el oriente y también en la Isla de la Juventud y la cayería Sabana-Camaguey. Una, dos, tres… ¡50 especies nuevas en una Isla donde, por más de un siglo, se habían conocido solamente cuatro! Justo delante de nuestras narices… mejor dicho, debajo de ellas y algunas literalmente escondidas bajo la tierra pues otras especies adaptadas exclusivamente a la vida en cuevas (=troglobias) habían sido detectadas. Todo un gigantesco tesoro.

Los círculos en el mapa y en las fotografías de ejemplares muestran la distribución y morfología externa en vista lateral de especies de Nescotolemon. Los círculos negros representan las especies conocidas actualmente y los rojos especies nuevas para la ciencia en proceso de descripción. La estrella negra representa la distribución dela especie cavernícola estricta (=Troglobia) Stygnomma fiskei, mientras que las estrellas rojas representan especies emparentadas colectadas en ambientes superficiales (=epígeas) que necesitan ser descritas para la ciencia. Fotos: Vanesa Mamani y Daniel N. Proud.

Recientemente, y gracias en gran parte a los esfuerzos de colecta del proyecto CarBio, liderado por Ingi Agnarsson de la Universidad de Islandia y Greta Binford de la Universidad Lewis y Clark en Portland, Oregón, EE.UU., hemos podido realizar los primeros análisis filogenéticos (contrucción hipótesis de relaciones evolutivas entre entidades biológicas) datados de las especies de Neoscotolemon y continúan dándonos sorpresas. Ahora sabemos que el género comenzó a diversificar en Cuba hace unos 34 millones de años y que las especies de Florida y Yucatán son resultados de dispersiones recientes desde Cuba hacia ambas penínsulas. También sabemos que el grupo hermano de Neoscotolemon es un grupo formado por una especie troglobia de Jamaica, Stygnomma fiskei—descrita por la opilionóloga española María Rambla Castells en 1969—y dos especies nuevas de Jamaica y Haití. Estas especies no pertenecen efectivamente al género Stygnomma y un nuevo género deberá ser oficialmente descrito para poder agruparlas.

Como pueden ver es ínfimo lo conocido oficialmente y muchísimo lo descubierto que todavía hay que publicar. Fue un camino que tardó mucho en forjar sus cimientos, pero que ya está fraguado y empezamos a andar. En conjunto con colegas y alumnos estamos trabajando para que en un futuro cercano todas estas nuevas especies engrosen oficialmente el elenco de la biodiversidad Antillana.

Y ya que mencioné un opilión de la Isla del Reggae, Jamaica, los invito a conocer más sobre sus tesoros escondidos. Tomemos, por ejemplo, los géneros Akdalima, Reventula y Ethobunus. Dos de los opilionólogos citados anteriormente fueron responsables por describir las especies jamaicanas de esos géneros. María Rambla trabajó con material colectado en 1968 por Stewart B. Peck de la Universidad de Carleton y Alan Fiske en aquel entonces de la Universidad de Harvard, durante un fugaz viaje de colecta de seis días a siete cuevas de la mitad occidental de la isla. Rambla publicó en 1969 la descripción de Cynortina pecki y Cynortina goodnighti las cuales actualmente están en el género Ethobunus. Una de ellas, Ethobunus pecki, es totalmente ciega (!), no solo carece de retina como tampoco mostraba rastros de ninguna estructura ocular, un fenómeno llamado “anoftalmía”. Esta característica, junto a otros rasgos morfológicos como la despigmentación y el alargamiento de los apéndices (patas y pedipalpos) son el reflejo de una perfecta adaptación al ambiente cavernícola. Por otro lado, Ethobunus goodnighti, presenta ojos funcionales (con retina), cuerpo pigmentado y apéndices cortos, lo que hace suponer que no es una especie troglobia y que también puede poseer poblaciones en el exterior de as cavernas (llamadas tecnicamente de especies troglófilas). Vladimír Šilhavý, estudiando los opiliones depositados en las colecciones del Museo de Zoología Comparada de Harvard, en 1979 publicó la especie Akdalima jamaicana, la cual ubicó en el género Akdalima que el mismo había creado dos años antes para una especie Mexicana (de Chiapas), y describió el género y especie nueva Reventula amabilis de las montañas de John Crow en la famosa región montañosa del oriente jamaiquino.

Más de 30 años después de la publicación de Šilhavý, tuve la extraordinaria posibilidad de unirme a una expedición científica a Jamaica organizada por el proyecto CarBio. Esta campaña no fue tan corta como los seis días de Stewart Peck, pero tampoco fue muy extensa, fueron unos 20 días de colectas y experiencias que permitieron muestrear varias localidades a lo largo y ancho de la Isla. Sin embargo, con solo este discreto esfuerzo de muestreo logramos casi cuatriplicar la diversidad insular conocida de Akdalima, Reventula y Ethobunus, pasando de cuatro a 15 especies y además colectamos un género nuevo (con dos especies nuevas) para la ciencia.

La gran sorpresa la dio el género Akdalima del cual fueron colectadas ocho especies nuevas mostrando un alto endemismo, lo cual hace sospechar sobre la existencia todavía de una gran diversidad por descubrir. Los análisis filogenéticos también mostraron que las “Akdalima” de Jamaica estaban más emparentadas con sus compatriotas Reventula (del cual aparecieron dos especies nuevas) que con las Akdalima chiapanecas. Ahora nos resta investigar si todas las especies de Jamaica son Reventula o si hay que describir un nuevo género para la ciencia… estamos trabajando en eso. Otras tres especies nuevas de Ethobunus se suman a las dos previamente conocidas de la Isla. Examinadas en detalle, son muy peculiares en cuanto a su morfología externa y genital y, definitivamente, muy diferente a los “verdaderos” Ethobunus que habitan en Costa Rica y Panamá. De nuevo, el complejo trabajo de definir un género para este grupo de especies antillanas se plantéa a nuestra frente como un desafío a enfrentar en el futuro.

Los círculos en el mapa y en las fotografías de ejemplares muestran la distribución y morfología externa en vista lateral de especies de Akdalima. El círculo negro representa a Akdalima jamaicana y los rojos constituyen especies nuevas para la ciencia en proceso de descripción. Las estrellas muestran la distribución y morfología externa en vista lateral de especies de Reventula. La estrella negra representa a Reventula amabilis y las rojas corresponden a especies nuevas. Los triángulos negros corresponden a Ethobunus pecki y Ethobunus goodnighti y los rojos a tres nuevas especies. Los triángulos invertidos de color marrón marcan la localización de dos especies nuevas de un género inédito para la ciencia. Fotos: Daniel N. Proud.

Al igual que en Cuba lo desconocido supera con creces lo conocido. Lo que más me llama la atención del ejemplo de Jamaica es que bastó una pequeña expedición de 20 días para superar ampliamente lo conocido por casi medio siglo. ¡Cuanto más podríamos develar con un muestreo sistemático, extensivo y un trabajo taxonómico priorizado sobre la fauna Antillana de artrópodos de suelo!

Creo que con los dos ejemplos expuestos los debo haber convencido de la enorme biodiversidad ignota de las Antillas, pero no quiero terminar sin hablar de la maravillosa Isla de La Española. Esta Isla de montañas que alcanzan los 3000 metros, alberga la fauna de Opiliones más desconocida de todas las Antillas. Y lo que es anecdótico, de algunos opiliones se conocieron primero las especies fósiles, atrapadas en los famosos depósitos de ámbar del Mioceno (de 15 a 20 millones de años de antigüedad), que sus representantes actuales. Este es el caso, precisamente, de un ejemplar fósil del género Kimula que había sido reportado por James C. Cokendolpher de Texas Tech University y George O. Poinar, Jr. de Oregon State en 1992 y que era el único kimúlido dominicano conocido. Esto se mantuvo durante ocho años hasta que en el 2000, describí conjuntamente con mi colega cubano y profesor, Luis F. de Armas a Kimula cokendolpheri la cual se mantiene hasta nuestros días como única especie viviente de este género en la Isla. Sin embargo (ya deben sospechar lo que voy a escribir), las colecciones del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural Prof. Eugenio de Jesús Marcano en Santo Domingo, República Dominicana, albergan más de 50 ejemplares entre los cuales hay, al menos, seis especies vivientes nuevas de Kimula para la isla de La Española. Tuve la oportunidad de identificar virtualmente estas especies y espero que, en un futuro no muy lejano, pueda tener el privilegio de estudiarlas.

Ejemplar de opilión depositado en la colección del Museo Nacional de Historia Natural Prof. Eugenio de Jesús Marcano en Santo Domingo, República Dominicana, que corresponde a una especie no descrita del género Kimula. Foto: Solanlly Carrero Jiménez.

Abel Pérez González is a biologist, arachnologist, spelunker, diver and a photography buff. He is a member of the Scientific Investigations Unit of the National Council of Scientific and Technical Research (CONICET). He works in the Arachnology Division of the Argentine Museum of Natural Sciences Bernardino Rivadavia,where he is also Associate Curator of the National Arachnology Collection. Twitter: @abelaracno Instagram: abelperez.g E-mail: abelaracno@gmail.com

I wish to thank all the professors, colleagues, students, curators, collectors and friends who have been so supportive during my 30 years of arachnological studies. Daniel N. Proud, Vanesa Mamani, Lázaro Echenique, Carlos A. Mancina, Aslam Ibrahim Castellón Maure y Solanlly Carrero Jiménez generously provided the photos for this article. Vanesa Mamani helped with the mapmaking. I thank Jill Yager for linguistic suggestions and corrections, and June Carolyn Erlick for editorial review and English translation.

Abel Pérez González es biólogo, aracnólogo, espeleólogo, buzo y aficionado a la fotografía.

También es miembro de la Carrera de Investigador Científico del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (CONICET) de Argentina. Trabaja en la División Aracnología, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales Bernardino Rivadavia, donde es, además, Curador Asociado de la Colección Nacional de Aracnología. Twitter: @abelaracno Instagram: abelperez.g E-mail: abelaracno@gmail.com

Agradezco a todos los profesores, colegas, alumnos, curadores, colectores y amigos que han sido un soporte esencial durante mis 30 años de estudios opilionológicos.

Daniel N. Proud, Vanesa Mamani, Lázaro Echenique, Carlos A. Mancina, Aslam Ibrahim Castellón Maure y Solanlly Carrero Jiménez gentilmente aportaron gran parte de las fotos utilizadas y Vanesa Mamani auxilió en la confección de los mapas. Agradezco a Jill Yager por sugerencias y correcciones linguísticas y a June Carolyn Erlick por la revisión editorial y la traducción al inglés.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Animals

Editor's LetterANIMALS! From the rainforests of Brazil to the crowded streets of Mexico City, animals are integral to life in Latin America and the Caribbean. During the height of the Covid-19 pandemic lockdowns, people throughout the region turned to pets for...

Where the Wild Things Aren’t Species Loss and Capitalisms in Latin America Since 1800

Five mass extinction events and several smaller crises have taken place throughout the 600 million years that complex life has existed on earth.

A Review of Memory Art in the Contemporary World: Confronting Violence in the Global South by Andreas Huyssen

I live in a country where the past is part of the present. Not only because films such as “Argentina 1985,” now nominated for an Oscar for best foreign film, recall the trial of the military juntas…