About the Author

Eduarda Lira de Araujo is a Ph.D. candidate in African and African American Studies. Her dissertation analyzes the social and political lives of African and Afro-Brazilian healers and diviners in 19th-century Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Her archival research was funded by the DRCLAS Brazil Research Grant in 2021-2022. She holds a BA in Africana Studies from Brown University.

Archival Sounds and Silences

Laroyê, Exu! This story of archival sounds and silences begins far from the National Archive in downtown Rio de Janeiro, where I spent most of my time bent over the frail pages of 19th-century court papers. It starts in the neighborhood of Realengo, in the outskirts of the city, where I went to visit my godmother, Célia Cristina Pereira de Araújo, and her mother, Valdelice, whom family and friends lovingly call Tia Val. The matriarch of the family, Tia Val has acquired spiritual knowledge and experienced wisdom that make her an important elder whom we often seek out for advice and guidance. As a child, I remember hearing her talk about the challenges she had encountered as a young girl who had migrated from the northeastern state of Bahia—fights she had to get into, the various moments in which she was defiant towards those who tried to treat her with contempt—and admiring her so much that I wanted to be courageous like her.

Sitting in Tia Val’s living room, drinking a cafezinho with her and other family members, I decided to tell her about some of the documents I had been reading in the National Archive, with research funded by the DRCLAS Brazil Research Grant (2021-2022). Researching the political imaginations and intellectual traditions of Africans and Afro-Brazilians in 19th-century Rio de Janeiro, I poured over court papers that documented the persecution of black healers and diviners. I hoped that Tia Val, in her own ways a practitioner of an Afro-Brazilian religion, would have advice as to how I could properly honor the stories, knowledge and practice of the people I had encountered in the violence of police records. So, I told her of Evaristo, a renowned spiritual leader arrested in the province of Rio de Janeiro when the police ambushed him in the middle of a healing ceremony and apprehended sacred, ritual objects. Aside from being persecuted for practicing “witchcraft” as a healer for the region’s free, enslaved and white slave-owning classes, Evaristo had allegedly been hiding runaway enslaved workers in his home, promising them freedom through spiritual practice.

Tia Val responded with no advice but a story from her own archive—one that had been preserved in her family’s oral tradition through generations, and which I will try to recount here with her permission, in my own words.

“My mother told me and my siblings this story, which her parents had told her, and we always thought it was important to pass it on” she began telling me. Adilina Maria de Jesus and Francisco Paulo de Jesus, Tia Val’s grandparents, were free or freed persons who lived on a small plot of land during the time of slavery. One day, a group of people running away from captivity approached their house asking for refuge and proposing to help work their land in exchange for shelter.

Despite their fear of being caught harboring runaway enslaved people, the family decided to let them stay, and took turns watching for anyone who could come their way searching for the runaways, she recounted. Cultivating the land together, they brought it to flourish into a plentiful harvest, which drew the attention of neighbors in the region. A few weeks later, they saw that a group of men mounted on horses were approaching the farm, likely to search for the fugitives in hiding.

Everyone was scared. Though Adilina and Francisco thought the group ought to leave in a hurry to escape, the fugitives decided to take another course of action. Instead of running away, they went inside and began playing the drums, Tia Val told me, instructing the hosts to let the men come. The sound of the drums and their singing in a language unknown to Tia Val’s grandparents filled the house. From these sounds emanated a thick fog, slowly engulfing the farm, the house, the room and everyone inside it. When the slave catchers arrived looking for the fugitives, they were told they were welcome to look around. With the fog that had suddenly descended upon the house, the men walked around the room but could barely see their own hands. They looked but could not see. The thick fog conjured through the sound of the drums hid the presence of the men and women who stood right there, unnoticed by the confused slave catchers.

As Tia Val related the incident, only the faint sound of the television remained in the background. Everyone in the living room stood in silence for a while.

“I believe it,” my godmother Célia responded. “Me too,” quickly followed by another daughter, echoed by cousins, nephews, my mom and other family friends who listened to the story in the living room.

Reverberations

The sounds from Tia Val’s family archive reverberate in my mind. And I take this complex, profound story seriously, as Harvard historian Alejandro de la Fuente urged me to do when I told him about this experience, warning me against impulses to secularize it. In a similar fashion, Harvard Divinity School’s Jacob Olupona, in his discussion of Yorùbá religion in his City of 201 Gods: Ilé-Ifè in Time, Space, and the Imagination (2011), proposes that we investigate myth, ritual and orality as expressions of African collective experiences and core ontological beliefs. Developing an African indigenous hermeneutics, he contends, demands us to dissolve the conceptions of rationality and linear historical progress that worked to differentiate Africans as the West’s “Other.” If instead we adopt Jamaican cultural theorist Sylvia Wynter’s notion of history as “the Word”—as discourse that concurrently narrates and creates the world—stories like Tia Val’s speak to an alternative narration and creation of a possible past. It is urgent that we take oral family archives such as this one into consideration in the building of an African and Afro-descendant history of Brazil. In fact, through their “Present Pasts” film collection, as well as their written work in Memórias do Cativeiro (2005), social historians Hebe Mattos, Martha Abreu and Ana Lugão Rios have brilliantly demonstrated the merit of discussing the history of slavery and abolition in Brazil through oral testimonies. Expanding on these scholars’ pathbreaking work, I think with Tia Val’s story to reflect on the meanings, limitations and possibilities of the various historical archives in their sounds and silences.

The memory of this event was so carefully kept within my godmother’s family for important reasons—I try to listen to the sounds of the story she shared with me. Tia Val’s story speaks to an ethics of collective existence and mutual aid that I still see in place in my godmother’s family. After all, behind her home, Tia Val built a second, smaller house that from time to time different relatives occupy, as financial difficulties and the need for free housing arise. This story tells us that solidarity and trust can be powerfully rewarded and recognized in the spiritual realm, which materializes as protection from harm, and also by abundance.

In Tia Val’s archive, fog is conjured and plays an important part in defining the course of her family’s history, guaranteeing their continued existence in freedom, reaffirming the righteousness of their political commitments. Were it not for the fog that descended upon Tia Val’s ancestors, they could have been indicted for sheltering runaway slaves, losing their freedom. More than that, they would have witnessed the fugitives, whom I can only imagine had become their friends, be taken back into captivity. The story she told us works as a compelling statement to the power of ancestral sounds—words, music—to render one invisible to the menacing white gaze. The sounds of this oral archive reveal other ways of existing, and spiritual technologies of survival to which people resorted when the worlds they had built came under attack. More than that, her story suggests the importance of other, non-human historical agents that made a collective existence possible.

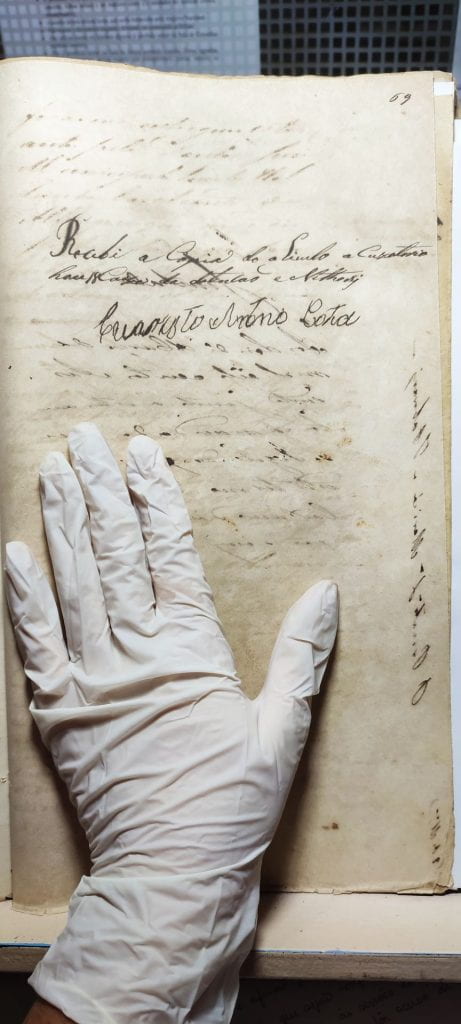

The story from Tia Val’s family archive also reverberates in the intellectual, political and spiritual practices of the healers and diviners I have encountered in the state archive. Yet, these records are full of the layered silences Haitian anthropologist Michel-Rolph Trouillot notably analyzed in Silencing the Past: Power and the Production of History (1995). Evaristo may very well be present in a conversation much like ours in another family’s living room somewhere else in Rio de Janeiro—and I hope he is. But to me, up to this point, his existence was only recorded through the filters of profound ignorance and virulent anti-Blackness of his case file. Police clerks selected which details to include or exclude from his interrogation, concealed irregularities in his arrest, misrepresented his practice and misspelled the names of the sacred objects apprehended with him. The chief of police collected testimonies of free and enslaved people likely intimidated and scared by the possibility of being arrested and humiliated like Evaristo if they testified to his capacity as a healer. Other witnesses were slave masters who simply claimed that Evaristo had “seduced” their enslaved workers into running away. The very questions posed to the witnesses were elaborated by policemen and prosecutors building their case against him. The case file has no record of the defense Evaristo’s lawyer made for him in court. His own defense was filtered once again by the questions believed to be relevant in court, and by whatever the clerk thought should (and shouldn’t) be written down. An illiterate man, Evaristo could not even read over the writing of his case file, after testifying, to approve or disapprove of it. The closest I may have gotten to him was the one instance, towards the end of his year in jail while awaiting trial, in which Evaristo seems to have signed his name himself—a trembling handwriting that missed some letters from his full name.

In the state archive there are no words that speak directly to Evaristo’s complexity of character—we don’t get a chance to see Evaristo as a person who was generous and selfish, talented, flawed, scared and courageous. We don’t know about the spiritual training he received to become a diviner and healer, or the powers he conjured when healing people who looked for his expertise. Black free and freed persons, enslaved workers, poor white men and women, slave masters and their families, all attended Evaristo’s healing and divination ceremonies, but we know little about them. In the document I read, Evaristo is portrayed as a charlatan who tried to lure people into giving him money. We know nothing of the process that led Evaristo to the decision of helping runaway slaves hide with him, in his house. Rather than solidarity, his decision is unanimously attributed to his alleged interest in exploiting the labor of the fugitives he helped escape from slave masters. I think of how Tia Val’s grandparents could have been accused of that, too, were it not for the music and the fog that stood between them and slave catchers.

Despite these archival silences, the story Tia Val shared with me makes me think of what University of Chicago historian Brodwyn Fischer, speaking in a seminar led by Brazilian historian Sidney Chalhoub at Harvard, “archival noise.” Tia Val’s archive offers us a glimpse into the possibilities we have in developing the “critical fabulations” Columbia University’s Saidyia Hartman calls on us to elaborate about people whose existence has been reduced to a state of nonbeing by the historical archive. What may have been the intellectual traditions informing Evaristo’s spiritual and political practices? What technologies did he resort to when facing danger? What solidarities and enmities shaped the contours of his social life?

Through the cracks in the police clerk’s words, we can find some noise: residues of Evaristo’s world-making activities. We can see a version of how Evaristo chose to defend himself in court and imagine how he reckoned with his arrest, how he reasoned with the law. As police officers and prosecutors called on witnesses to testify to Evaristo’s supposed charlatanism, we may begin to understand Evaristo’s social life—the people he knew, those he helped, people he may have trusted and who trusted him, people to whom he lent money and people from whom he borrowed, people who lived with him.

One of these witnesses, for instance, was a slave master who had allegedly called upon Evaristo to cure his wife of a mysterious illness. According to that witness, Evaristo’s divination revealed that his wife would only be cured if the slave master signed a letter of manumission for Joana, a young woman he enslaved on his property. The man signed on to Joana’s manumission. If we secularized Evaristo’s activities, we could think of him simply leveraging his power as a respected healer to give this woman, whom he might have known, her freedom. But more interesting than that, perhaps, would be to think of the concept of sacrifice and religious offering, as well as notions of health that may have informed Evaristo’s practice when he and the spiritual realm worked to free Joana from captivity. We know that in some Central African spiritual traditions, for instance, illness is not only the result of bodily biological processes, but also of social and spiritual disruptions and imbalances. It would make sense that Evaristo might have seen slavery as a source of social and spiritual illness for slave masters and enslaved workers alike.

Despite the silences and the violence of the records on Evaristo, we can hear the sacred totems, tools and charms that were apprehended and listed in his case file, which we may link to spiritual practices in West and Central Africa, and in Indigenous communities in Brazil. Suddenly, mighty animals, powerful plants, and other elements begin to appear in Evaristo’s story, like the fog that descended upon Tia Val’s grandparents’ place.

Records I have encountered suggest that Evaristo did not cease to work as a healer and diviner after his conviction was overturned on appeal—it seems like his activities persisted for a long time after his arrest and dismissal. The fact that he was able to continue his work for so long may speak precisely to his ability to conjure protections and create worlds of collective abundance out of a liminal space for existence in a white supremacist society. The silences in Evaristo’s case files and the sounds of Tia Val’s family archive can help us expand our ideas of what constitutes an archive, asking ourselves what it means, truly, to take these stories seriously.

More Student Views

Río Piedras: As a Desert Flower Blooms in the Night

The sunset of my first day at the Harvard Puerto Rico Winter Institute (HPRWI) painted the sky with violet and magenta. It felt as if the day had just begun.

Colombian Women Who Empower Dreams

English + Español

The verraquera of Colombian women knows no bounds. This was the message left with me by the March 30 symposium, “Empowering Dreams: 1st symposium in honor to Colombian women at Harvard.”

A Review of Born in Blood and Fire

The fourth edition of Born in Blood and Fire is a concise yet comprehensive account of the intriguing history of Latin America and will be followed this year by a fifth edition.