Knowledgeable Bodies

Basque Traditional Dance and Nationalism

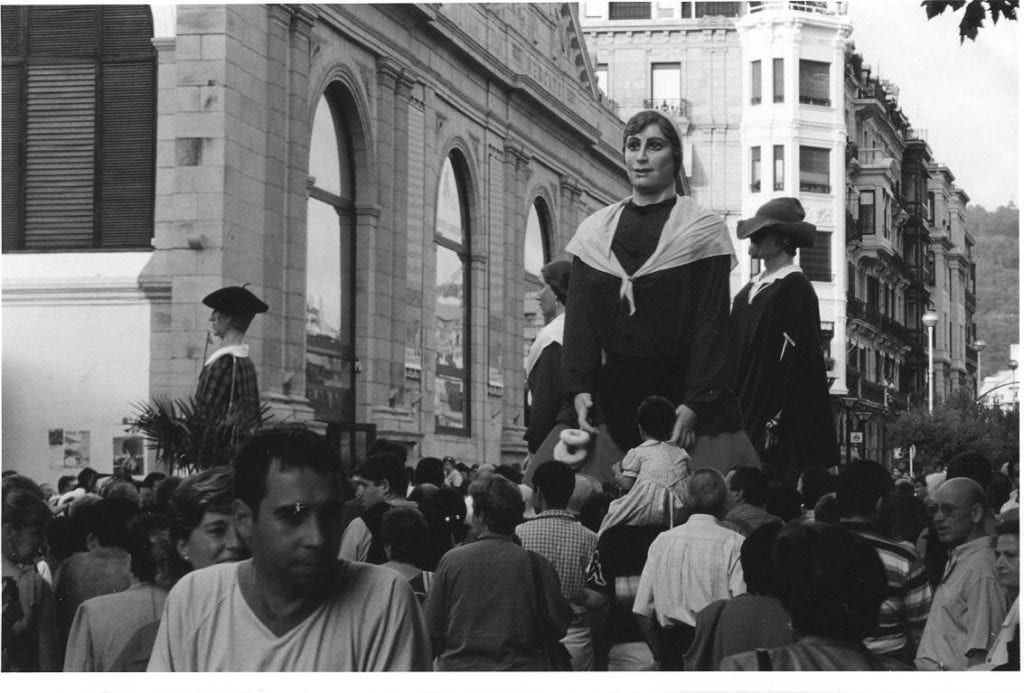

The large figure of a typical Basque farmer is paraded down the street during a festival. Photo by Suzanne Jenkins

Imagine you are vacationing on the beach in Spain. What if you step out of your hotel on the first morning and see masses of people swarming toward you, brandishing flags and shouting in a language you don’t understand, as masked policemen clad in black and red jump suits and big black boots encourage order? Down at the plaza, silent attention to speeches alternates with loud chanting. Fists jut into the air, unmoving. Would you feel frightened? Annoyed at having your path to the bakery across the street obstructed? Feel a sense of thrill that something interesting is happening? Would you feel Basque?

Chances are it is easy for you to imagine feeling fear, annoyance or thrill because you have experienced these sensations before. I don’t need to explain them to you in scientific terms. You likely are not sure what it means to feel Basque, however, if you are not Basque.

I heard the statement “I feel Basque” over and over again while I researched the connection between Basque traditional dance and nationalism in San Sebastián, Spain, for my thesis in social anthropology, and it often left me frustrated. Through interviews with dancers, I came to accept that it refers to a feeling in the body as tangible as fear or thrill that can be triggered by Basque dance, music, language, style of dress or any number of cultural markers. Words cannot adequately convey this feeling to outsiders. Accordingly, the feeling reinforces solidarity within the group and a conviction of being truly different from other people.

Recognizing these physical sensations as a type of insider knowledge both supports and adds to Harvard professor of anthropology Michael Herzfeld’s understanding of nationalism as cultural intimacy. It helps explain how nationalism can be experienced as a natural, concrete and extraordinarily motivating force.

BASQUE TRADITIONAL DANCE AND NATIONALISM

Like the Basque language, which is strikingly unrelated to any other Indo-European language, Basque folk dance is a distinguishing element of Basque culture. As the Basque provincial government pursues diplomatic strategies towards independence from Spain, it encourages studies about dance and language to bolster its arguments. Many anthropological studies have read choreography as narrative, arguing that Basque folk dance’s historical-cultural images evidence a continuously autonomous culture and social system since ancient times (Fronteras y puentes culturales: danza tradicional e identidad social by Kepa Fernández de Larrinoa, 1998 and La danza tradicional by Emilio Javier Dueñas, 2002).

To keep the dance form alive, however, the government depends upon the individual dancers who dedicate hours and hours to their practice, usually without pay. Some of them dramatically link nationalist emotions to the question of survival. “It’s that we live it much more—much more because we have to fight daily. …In the Basque Country we are very nationalist because we feel our country, since historically they have wanted to, well they have wanted to crush us in one way or another so that we couldn’t subsist. We have had to work hard in order to subsist. In the end, we feel our, our roots deeply,” said one dancer (Personal Interview, August 22, 2002). I set out to discover what dancing the traditional form means to them.

NERVES AND GOOSE BUMPS

The dancers’ stories tell of a parallel surrender into physicality and the collective Basque identity. Basque traditional dance has a demanding physical technique, similar in some ways to classical ballet. Over time, the dancers feel their muscles gain flexibility and strength; they breathe more easily through difficult exercises, and they move with increasing technical agility. At performance time, they trust their bodies to perform the steps correctly. Gotzon is a dancer in a semi-professional company that fuses traditional and contemporary dance. When he dances well, he experiences sensations of fluidity. “I don’t think,” he says, “I let myself go. I let the music carry me. If you think, you mess up.” Eneko, a traditional dancer, remembers learning a particularly difficult jump. He had to think a lot in the beginning, but after repeated physical practice, he says, “I don’t have to think as much. I jump, and I do it.”

As they release into physicality, they release their individual identity into a collective ideal. Aida, the leader of the girls in the traditional dance company Goizaldi, says that when she performs, “I’m no longer Aida, the person. I am like all of history.” Fellow company member Sua says that when you step on stage, you are “your nation’s ideal person.”

Performing this ideal can evoke both thrill and nervousness. Aida’s favorite dance is called the agurra. Intended to welcome an honored person (agur is the traditional Basque greeting), it is always the first dance that the girls perform in Goizaldi’s performances. Dancing the agurra gives Aida goose bumps, she says. So does dancing with the ikurriña—the Basque flag. She tries to describe a regional celebration in which a large gathering of groups performed simultaneously. “We all, all the guys and girls, crouched down, and then there were a ton of ikurriñas…” Words fail her. Her breath catches in her chest, and her eyes close. Chills run down her spine. She breathes deeply before opening her eyes to stare straight into me, shaking her head. She doesn’t go on, but I already have goose bumps. In the United States, I have performed classical and contemporary dance, and I know a similar thrill of performance. If you are a baseball fan, perhaps it is similar to the excitement of having the Red Sox take the lead away from the Yankees (or vice versa).

Aida emphatically believes that a Spaniard or other non-Basque “would never have this feeling. For him, dancing the agurra wouldn’t mean anything. But for us, it means a lot, a lot. It’s very emotional.” When she watches Basque dance, she has difficulty sitting back and enjoying the show. She gets nervous for the performers and feels the urge to be dancing herself. On the other hand, she can easily sit perfectly detached when she watches other cultural groups perform.

Nervousness evokes similarly tangible sensations. A dancer feels his agitated nerves when he feels his heart pulsing inside his chest, his stomach disconcertingly floating up between his shoulders, and his breath falling shallow. Some dancers get more nervous than others, but each dancer feels more nervous performing within the Basque Country than during international tours. Sua describes it, “I get much more nervous when I’m with my people. When you’re on tour, you can dance much more calmly. They don’t know the dances, you see? Even if you screw up it doesn’t matter because they don’t notice. On the other hand, last week in the Plaza de la Constitución, it was totally full of people, and of course… it’s not just any audience. It’s an audience that knows about these things. There are dantzaris [traditional dancers]. It’s an audience that demands a lot from you. And it can pick out your mistakes. I get much more nervous, much more.” (Personal interview, August 22, 2002)

These dancers actually feel their commonality with other Basques and their difference from other peoples. Thus, Basque identity can be “carried inside” in a real way at the same time that it can be constructed through experience. One of the dancers in Goizaldi was born to non-Basque parents but has grown up in the Basque Country with a Basque nanny, speaking Basque, eating Basque food and dancing the traditional Basque form. He feels Basque and is considered to be Basque by the other company members. Another company member tells a similar story about his grandmother. Henri Lamarca, a “native of Catalonia without a single tie to the Basque Country,” wrote in 1977 about his experience coming to “feel profoundly Basque” after dancing in a traditional dance group for many years [my translation] (La danza folklórica vasca como vehículo de la ideología nacionalista, 1977).

CULTURAL INTIMACY

This view of “feeling Basque” complements Herzfeld’s theory of nationalism as cultural intimacy in three important ways (Cultural Intimacy: Social Poetics in the Nation-state, 1997). The notion of cultural intimacy is based on the sharing of insider information. It is “the recognition of those aspects of a cultural identity that are considered a source of external embarrassment but that nevertheless provide insiders with their assurance of common sociality.”

First, Herzfeld’s definition addresses information that a group can share with outsiders but would like to hide on purpose. “Feeling Basque” cannot be conveyed to outsiders through verbal communication. Therefore, it appears as a natural barrier between Basques and non-Basques—authentic and not subject to manipulation.

Second, it exemplifies how cultural intimacy accounts for nationalists’ perception of the nation as concrete fact, whereas Benedict Anderson’s model of nationalism as “imagined community” limits the nation to an abstract “imagined” realm. Understanding the Basque feeling as a physical sensation recognizes that insider information can reside in the body in tangible form, not just in the mind or imagination. An outsider cannot dispute the existence of these feelings.

Third, it suggests another reason why nationalism may have such strong motivational power. Sensations of feeling Basque are a form of information or knowledge upon which individuals make choices—akin to Anthony Giddens’ practical consciousness (Central Problems in Social Theory: Action, Structure and Contradiction in Social Analysis, 1979) or Pierre Bourdieu’s habitus (Outline of a Theory of Practice, 1977). Knowledge, however, is situated. According to Giddens, “we have to recognize that what an actor knows as a competent—but historically and spatially located—member of society, ‘shades off’ in contexts that stretch beyond those of his or her day-to-day activity.” A conspicuous threat to identity threatens to uproot an actor from the perceptual context of his everyday life. This, in turn, jeopardizes an actor’s competence. An actor should have strong incentive to protect his identity in order to protect his competence.

BY DEGREES

I came to realize that I can never understand on an intellectual level what it means to feel Basque. I can only accept that the dancers actually feel Basque, and that they make choices based upon this feeling.

However, as my friend Zigor Salvador from San Sebastián says, “It’s not like either you’re Basque or you’re not. Depending on your life, your family origin, your relationships with other areas of Spain or even the world, your Basque ‘gauge’ can and does change during a lifetime. You can begin your adult life feeling very Basque and then have the feeling lessen as you travel, see the big wide world and interact with other cultures, or you can come from a Spanish family and end up being a fundamentalist or radical Basque. Either way, meaningful communication can only succeed when you acknowledge the quantitative nature of the feeling, and you realize that all the people living here are somewhat Basque. They may only like a particular Basque sport, or the Basque gastronomical heritage, or they simply like the landscape, the mountains, the sea. Endless combinations of the very bits that make up the Basque feeling exist, and each person is unique regarding such feelings. Realizing this, you can somehow get attached to every other member of the society. Empathy opens the doors for communication, and the middle point exists.”

Goizaldi asks audiences to acknowledge this each time it performs. It always seeks to perform under the Basque flag rather than the Spanish flag, in part because the Spanish flag is akin to false advertising—the audience will expect to see flamenco, when in reality it is going to hear “not even one ‘olé!’” Also, the dancers want to combat the stereotypes associated with being Basque. They complain that outsiders tend to “put them all in the same sack”—if you display an ikurriña, “you are already an assassin.”

When Basque dancers perform, they invite both local and international audiences to acknowledge a positive side of the Basque identity and each dancer’s membership in it. The audience is left to choose whether or not to accept.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Dance!

We were little black cats with white whiskers and long tails. One musical number from my one and only dance performance—in the fifth grade—has always stuck in my head. It was called “Hernando’s Hideaway,” a rhythm I was told was a tango from a faraway place called Argentina.

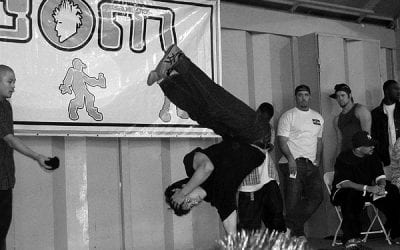

Brazilian Breakdancing

When you think about breakdancing, images of kids popping, locking, and wind-milling, hand- standing, shoulder-rolling, and hand-jumping, might come to mind. And those kids might be city kids dancing in vacant lots and playgrounds. Now, New England kids of all classes and cultures are getting a chance to practice break-dancing in their school gyms and then go learn about it in a teaching unit designed by Veronica …

Dance Revolution: Creating Global Citizens in the Favelas of Rio

Yolanda Demétrio stares out the window of our public bus in Rio de Janeiro, on our way to visit her dance colleagues at Rio’s avant-garde cultural center, Fundição Progresso. Yolanda is a 37-year-old dance teacher, homeowner, social entrepreneur and former favela (Brazilian urban shantytown) resident. She is the founder and director of Espaço Aberto (Open Space), an organization through which Yolanda has nearly …