Looking Back

Reflections on the Pandemic from Lima, Peru

Writing about the experience of this pandemic has been more difficult than I imagined. When I was invited to do this article, we were still in a very uncertain moment of the pandemic. It was September 2021 and, even if we already had vaccines, the predominant variants of Covid-19 were still a major threat to health and life itself.

Now, at the end of June 2022, when I revisit the idea of writing this text, the situation is completely different. Although it is true that uncertainty reigns—particularly about the possible surge of new variants and about long Covid or the possibility of another pandemic—the major difference is that the prevailing variant today of Covid-19 generally is not fatal.

Perhaps that’s why I feel more disposed to share my experience, to look back and reflect on the way the pandemic was handled in Peru. I refer not only to the historical and cultural aspects that led us to opt for draconian measures with military support, but also to the precariousness of our health and education systems that impeded interaction and in-person learning in classrooms for more than two years.

My experience in the pandemic is not special or extraordinary. I spent the pandemic at home with my family, with a job, and with all basic necessities. Despite these optimum conditions of life—the privilege of a few—it was all exhausting: the confinement, having to adapt to remote work and accompany my daughters in their remote studies, the anguished uncertainty in the face of the virus, the draining fear of contagion, the worry about more vulnerable people, the bleak daily account of anonymous deaths and the inevitable, immense sadness for the loss of relatives, friends and colleagues, all healthy before the pandemic.

How do I recall how everything began? Where was I? What was I doing? In March 2020, I was in Lima, preparing scripts for interviews and participant observation to do ethnographic fieldwork in two rural districts of Peru, Masisea in Ucayali and Acoria in Huancavelica respectively located in the Amazons and the high Andes. I wanted to find out what local officials did, formally and informally, to guarantee that boys, girls and adolescents in the rural zone attended school and finished their education. No one could have imagined that two weeks later, the entire country (and the world) would stop, that I would not get to visit these zones as had been planned, and that school studies would become as impossible as they were urgent. Because if something has been required in these times of pandemic, it is to rely on information and resources to help boys, girls and adolescent continue their studies, especially those in scattered rural zones far from the city.

The Peruvian government established the quarantine Sunday, March 15, 2020, declaring a national state of emergency and ordering mandatory social isolation for fifteen days. The government gave 24 hours for people to arrange confinement. That is to say, where, with whom, how and with what provisions one would spend the two weeks of confinement that started Monday, March 16, at 11:59 p.m. Some families hurried to supply themselves with basic goods—the massive and desperate purchase of toilet paper was a phenomenon that happened in many corners of the world, perhaps as response in the face of anxiety and uncertainty. They took precautions to provide for the more vulnerable of the extended family, those with special needs, the little ones and the elderly. But the truth is that most of us assumed it would only be two weeks, at the most a month, and then we would get back to our normal life.

Nothing could be further from the reality. Classes in public schools were scheduled to start up again in April 2020, but that never happened in person; a few private schools had opened just the week before the lockdown, but most private and public schools remained closed during all of 2020 and 2021. Thirteeen months after the beginning of the quarentine, Sunday April 11, 2021, when I went to vote for the new president and congressional representatives at a school near my home, I was startled to see the date “Friday, March 13, 2020,” written on the blackboard. In Peru, voting is compulsory and takes place in schoolrooms. Thus, the blackboards reflected—without knowing it—what would be the last day of school in the few private schools whose academic year began in March 2020. Since that Friday, no one had set foot in a classroom. What is even more terrible is that it would be another whole year before students returned to their classrooms. I remember looking at that blackboard somewhat confused because even though it reflected time had stopped, so much had happened in the meanwhile.

The first stage of the pandemic was critical, then: there were those who survived without getting sick—the privilege of a few; those who survived the disease—the luck of some; but all of us, absolutely all in these long pandemic, have lost someone close to us. The tragedy of the loss was preceded by anguish, despair and frustration to try to get a bed in intensive care or oxygen tanks to attend to the patient at home. In this context, the price of oxygen soared tenfold to 8,000 soles—$2,300—for a 10-cubic meter cylinder.

“Health Worker Infected” Photo by Rodrigo Abd, who won first place in the DRCLAS photo contest, “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America” with his series “The Virus Strips Peru.”

The impossibility of saying goodbye and the pain of the loss, the absence of rites of passage and consoling hugs added other layers of anguish to the severity of the disease. Grieving families isolated and in debt. A tragedy of unimaginable proportions.

“Collecting the Dead” Photo by Rodrigo Abd, who won first place in the DRCLAS photo contest, “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America” with his series “The Virus Strips Peru.”

In mid-March 2020, it was imposible to foresee what was coming. Of course the pandemic is a world-wide phenomenon and many other countries have endured similar conditions, but the Peruvian case is worrisome because although it has been recognized as a model country in the region for its economic management, it proved to be one of those worse equipped to confront the pandemic: the collapse of an unequal, deficient health system; inadequate provision of potable and clean water and the sudden suspension of informal work and self-employment that provides sustenance to many Peruvians during the long pandemic. By April 2020, 31% of the population was unemployed; this situation affected mostly the poor and those in the informal economy (IEP, 2021).

These problems explain why—in spite of being one of the countries that mandated a severe and long quarantine—Peru was one of the countries with the greatest human loss per capita. As a result, it is the country with the greatest number of orphans left by the pandemic.

But, to help you understand our experience better, I want to stop a minute to reflect on our Peruvian-style confinement. With the declaration of a countrywide state of emergency, “constitutional rights in regards to freedom and personal sfety, the inviolability of the home and freedom of assembly and mobility throughout the territory” were suspended. The social isolation was very strict, allowing only one person per family to go shopping near their home, that is, people could not go out freely to walk, and, much less, be accompanied. Public transportation—both metropolitan and intercity —was shut down. One couldn’t even drive one’s own car without a special permit reserved for authorized activities (health services, provisions of food and transport services). The borders were closed and all types of international transportation were banned.

In the midst of this long and strict confinement, in April 2020, people began a mass migration out of Lima. Thousands of people decided to go back on foot to their home towns or those of their parents or grandparents. It was a large-scale defiance of the state of emergency because the obligatory lockdown to save people from the virus made no sense without water, food or work. The Peruvian state had little to offer to keep them at home: in April, it distributed the first subsidy dubbed “I’ll Stay at Home,” 380 soles or around US$120, to aid the poorest Peruvians, most of whom were self-employed or in the informal sector. It was a palliative measure in the midst of an emergency, but the selection of the beneficiaries and means of distribution faced enormous difficulties.

“Escaping from Lima” Photo by Rodrigo Abd, who won first place in the DRCLAS photo contest, “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America” with his series “The Virus Strips Peru.”

The city of Lima, which previously had held out the promise of a better life, had become unlivable during the pandemic. Those families without water orndrainage, without work, without health insurance, saw the migration to the provinces as their only salvation. It was a wrenching scene. Moreover, many of these travelers were former migrants (or immigrants), many of them forcibly displaced, who came in similar situations in previous decades (or recently), fleeing violence, poverty and the lack of opportunity. The regional governments had to invest in buses to transport the walkers, but at the same time, feared that they would bring the virus to the provinces, whose health services were even more precarious than those of Lima. We have a registry of 167,000 people who ended up using the buses, but many others just kept walking to their ancestral towns.

Brigades of police and armed soldiers patrolled the streets, plazas, parks and beaches, and some of Lima’s main avenues hosted war tanks that made sure the rules were obeyed. A curfew was imposed between 8 p.m. and 5 a.m. in which no one could leave their homes, except for medical emergencies.

No one went out in my house, not even to shop. I ordered everything on line, but since delivery sometimes could take weeks and also imposed limits on goods such as soap, alcohol, flour and toilet paper, I had to keep ordering from different suppliers. When the order arrived, we set out to disinfect each and every one of the products. My daughters were overwhelmed by social distancing and the sudden change to online learning—the youngest in her last year of high school and the oldest in her third year of college. Although they helped as much as they could, the greatest burden fell on the adults, who were also trying to work remotely. Impossible to complain though while thousands were without work. The Internet crashed quite often. The screens were our world and the different virtual platforms defined all our interactions—work meetings, teaching clases, gatherings with friends, conversations with relatives, chats, therapies, training, shopping, everything—in a exhausting hyperconnectivity that was also our salvation.

This confinement lasted four long months. President Martín Vizcarra made daily announcements over television in which he informed the public about the expansion of the virus and the policy decisions to stop that spread in its tracks. Thus the obligatory social isolation that began with fifteen days of confinement was slowly extended. Finally it ended after 120 days of strict confinement and isolation.

What’s certain is that even when the quarantine was “lifted,” the declaration of the state of emergency remained in effect. Thus, restrictions and curfew continued. The government did not end it until January 31, 2022, that is, 22 months after the beginning of the quarantine.

In a post-conflict society like that of Peru, the declaration of a state of emergency, the guarding of the streets by military personell and curfews are measures that have a history. Because of that, just their mention evokes other memories of violence, terror, chaos and also of abuses by law enforcement. I remember my surprise and uneasiness when I heard that a state of emergency had been declared. And later, seeing Lima’s main avenues occupied by tanks with young soldiers controlling people’s movements—and arresting violators—was a very disturbing image that far from giving me tranquility or security, upset me, doubtless because of my memories of the political violence wracking the country during the 80s and 90s.

The president of the republic himself made this link with our history of violence explicit and quickly popularized the use of warlike language to confront the pandemic: “I do not have the least bit of doubt that we will win this war because we Peruvians fulfil our functions and you represent that. They defend their motherland when it is necessary; they confront terrorism and they are fighting other enemies like drug trafficking and crime, but today they are facing another silent enemy.” (El Peruano, April 16, 2020).

The link to the past was also experienced in the constant threat to life, in the suffering to obtain a hospital bed or a tank of oxygen, and death itself came without any possible goodbyes or rites, situations that appeared as a mirror of the pain and anxiety that thousands of families confronted during the violence of the 80s and 90s and that families still suffer as they search for their disappeared relatives. For many families, it’s adding fuel to the fire: the premature departure of relatives at the hand of a “silent enemy” does not feel like a new story, but a recurring nightmare.

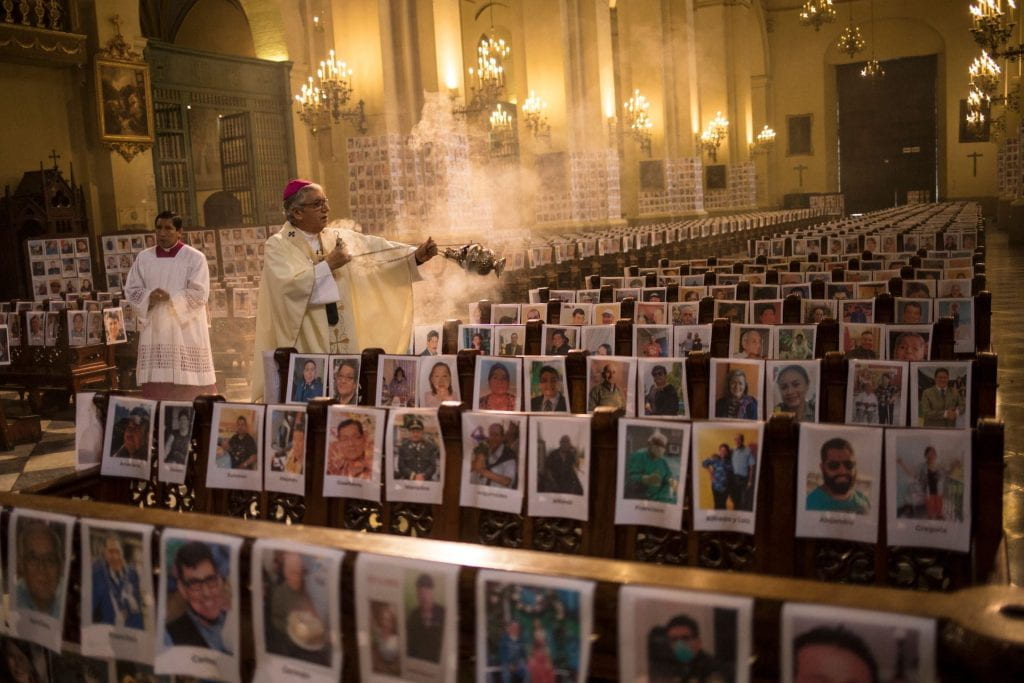

“Mass for the Dead” Photo by Rodrigo Abd, who won first place in the DRCLAS photo contest, “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America” with his series “The Virus Strips Peru.”

Added to this national mourning for the loss of human life, for the increase in poverty and the vulnerability of thousands of families is a political instability without precedents. During the worst crisis of the pandemic (2020-2021), we had three presidents, five health ministers, two education ministers and endless corruption scandals, among them, Vacunagate, the revelation that the Peruvian government had distributed quantities of the Chinese vaccine in acts of favoritism, while the public confronted an impossible vaccine shortage. In short, the pandemic developed in the context of tremendous economic and political crisis that has continued and, at times, appears we have become prisoners of that situation.

In addition, Peru is one of the countries that has delayed the most in returning to in-person classes. In spite of the state effort to develop a virtual platform for remote education (with the program “I Learn at Home,” Programa Aprendo en Casa), hundreds of thousands of students had their education completely interrupted and the great majority of the nation’s students kept up with their remote studies in a precarious and unequal way, especially students in the rural areas without connectivity. Taking into account that our academic calendar goes from March to December, this means that most boys, girls and adolescents and all of those who are studying at a post-secondary level have spent two full years without setting foot in a classroom.

Peru’s experience in the pandemic is like a magnifying glass to show the worst and best for every individual, family, community and the country as a whole. Without a doubt, there have been enormous examples of solidarity, help and accompaniment in the face of scarcity, desperation, grief and abandonment. But the balance is negative and it is urgent to review critically the experiences of the pandemic and to do something about our historic deficits as a society.

Mirar Atrás

Por Francesca Uccelli

Escribir sobre lo vivido en esta pandemia me ha resultado más difícil de lo que imaginé. Cuando me invitaron a escribir este artículo estábamos aún en un momento muy incierto de la pandemia. Era septiembre del 2021 y, si bien ya contábamos con vacunas, todavía las variantes predominantes del Covid-19 eran muy riesgosas para la salud y la vida.

Hoy, a fines de junio 2022, cuando retomo la idea de escribir este texto el escenario es otro. Aunque es cierto que prevalece cierta incertidumbre —sobre el posible surgimiento de otras variantes, las secuelas que pueda dejar a largo plazo el contagio o la posibilidad de otra pandemia— la gran diferencia es que la variante predominante del Covid-19 hoy generalmente no es letal.

Quizás es por eso que me siento en mejor disposición para compartir lo vivido, para mirar atrás y reflexionar sobre el modo en que se lidió con la pandemia en el Perú. Me refiero tanto a los aspectos históricos y culturales que nos llevaron a optar por medidas punitivas con apoyo militar, como a la precariedad de nuestros sistemas de salud y educación que impidió la interacción y el aprendizaje presencial en las aulas por dos años.

Mi experiencia en la pandemia no es particular ni extraordinaria. La pandemia la pasé en mi casa, con mi familia, con trabajo y sin que nos faltara ninguna necesidad básica. A pesar de estas óptimas condiciones de vida –que no debieran ser un privilegio de pocos—todo fue muy duro: el encierro, adaptarse al trabajo remoto y acompañar el estudio remoto de mis hijas, angustiante la incertidumbre ante el virus, desgastante el miedo al contagio, constante la preocupación por las personas más vulnerables, desolador el conteo diario de muertes anónimas, y lo inevitable, la inmensa tristeza por la pérdida de familiares, amigos y colegas, todos sanos antes de la pandemia.

¿Cómo recuerdo que empezó todo? ¿Dónde estaba? ¿Qué estaba haciendo? En marzo del 2020 me encontraba en Lima preparando las guías de entrevista y observación etnográfica para ir a hacer trabajo de campo en dos distritos rurales del Perú, Masisea en Ucayali y Acoria en Huancavelica; ubicados en la zona amazónica y altoandina, respectivamente. El objetivo era conocer lo que los funcionarios locales hacían, formal e informalmente, para garantizar que niños, niñas y adolescentes en zona rural asistan, permanezcan y terminen su educación. Nadie podía imaginar que dos semanas después, el país entero (y el mundo) se detendría, que no llegaría a visitar estas zonas como había planeado y que el estudio sería tan irrealizable como urgente. Porque si algo hemos requerido en estos tiempos de pandemia es contar con información y recursos para ayudar a que niños, niñas, adolescentes y jóvenes puedan continuar estudiando, especialmente los ubicados en zonas rurales dispersas y alejadas de las ciudades.

La cuarentena se declaró el domingo 15 de marzo del 2020 a través del Decreto Supremo Nº 044-2020-PCM que estableció el estado de emergencia nacional y dispuso el aislamiento social obligatorio por quince días. El gobierno otorgó 24 horas para organizar el confinamiento. Es decir, adónde, con quiénes, cómo y con qué pasarías las dos semanas de encierro a partir del lunes 16 de marzo a las 23:59 horas. Algunas familias corrieron a proveerse de lo básico –la compra masiva y desesperada del papel higiénico fue un fenómeno que se dio en muchas partes del mundo quizás como una respuesta ante la ansiedad de la incertidumbre– y a tomar medidas para asegurar la atención de los más vulnerables del círculo familiar, aquellos con necesidades especiales, los más pequeños y los ancianos. Pero la verdad es que la gran mayoría asumimos que serían solo dos semanas, a lo más un mes, y que después retomaríamos la vida.

Nada más lejano de la realidad. Las clases en las escuelas públicas estaban programadas para iniciar en abril del 2020, pero nunca se dieron presencialmente; algunos colegios privados habían iniciado las clases la semana previa al cierre; pero la gran mayoría de colegios públicos y privados permanecerían cerrados durante todo el 2020 y el 2021.

Trece meses después del inicio de la cuarentena, el domingo 11 de abril del 2021, cuando fui a votar por nuevo presidente y congreso a un colegio cercano a mi casa, fue impresionante encontrar la fecha escrita en la pizarra: “viernes 13 marzo del 2020”. En el Perú las elecciones son obligatorias y se realizan en locales escolares, por tanto, las pizarras registraron –sin saberlo—lo que sería el último día de clases del 2020 en los pocos colegios privados que iniciaron en marzo 2020. Por tanto, desde ese viernes de marzo nadie había vuelto a pisar esas aulas. Y lo más terrible, la mayoría de nuestros estudiantes tardarían todavía un año adicional en regresar. Recuerdo mirar la pizarra con cierta confusión porque a pesar de reflejar un tiempo detenido, en realidad, muchísimo había sucedido.

La primera etapa de la pandemia fue crítica y, entonces, hubo los que sobrevivimos sin enfermarnos —un privilegio de pocos—; los que sobrevivieron la enfermedad —una suerte de algunos—; pero todos, absolutamente todos, en esta larga pandemia hemos perdido a alguien cercano. La tragedia de la pérdida estuvo precedida por la angustia, la desesperación y la frustración por conseguir una cama en cuidados intensivos o balones de oxígeno para atender al paciente en casa. En este contexto, el precio del oxígeno subió a más de diez veces su valor (alrededor de 8,000 soles – 2,300 dolares– por un cilindro de 10 metros cúbico).

“Health Worker Infected” Photo by Rodrigo Abd, who won first place in the DRCLAS photo contest, “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America” with his series “The Virus Strips Peru.”

Ante la gravedad de la enfermedad se sumó la imposibilidad de la despedida y al dolor de la pérdida, la ausencia de rito de pasaje y de abrazos de consuelo. Familias de luto aisladas y endeudadas. Una tragedia de proporciones inimaginables.

“Collecting the Dead” Photo by Rodrigo Abd, who won first place in the DRCLAS photo contest, “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America” with his series “The Virus Strips Peru.”

A mediados de marzo 2020 era imposible prever lo que se venía. Por supuesto que la pandemia es un fenómeno mundial y muchos otros países han pasado por similares condiciones, pero el caso peruano es preocupante porque a pesar de haber sido reconocido como un país modelo en la región en el manejo económico durante las últimas décadas, mostró ser uno de los peor equipados para enfrentar la pandemia mostrado por el colapso de un sistema de salud desigual, deficiente, una inadecuada provisión de agua potable y saneamiento en los hogares, y la suspensión súbita del trabajo informal y autoempleo, que sostiene muchos peruanos y peruanas. Para abril del 2020, el 31% de la población se había quedado sin trabajo, esta situación impactó principalmente a los sectores más pobres y a los trabajadores independientes (IEP, 2020).

Estos problemas explican porque —a pesar de ser uno de los países que más tempranamente entró en un severo y largo confinamiento— Perú fue el país con mayores pérdidas humanas en relación con su población y como consecuencia, el país con mayor número de huérfanos dejados por la pandemia.

Pero, para comprender mejor lo vivido, quiero detenerme a dar cuenta del encierro a la peruana. Con la declaración de emergencia a nivel nacional quedaron suspendidos “los derechos constitucionales relativos a la libertad y la seguridad personales, la inviolabilidad del domicilio, y la libertad de reunión y de tránsito en el territorio”. El el aislamiento social obligatorio fue estricto e implicó que solo una persona por familia podía salir a comprar cerca de la vivienda, es decir, no se podía salir a caminar libremente y mucho menos acompañado. Los espacios públicos estaban cerrados y no había servicio de transporte público local ni interprovincial, ni se podía usar el vehículo propio sin un permiso especial reservado para actividades autorizadas (servicios de salud, provisión de alimentos o servicio de transporte). Del mismo modo quedaron cerradas las fronteras y prohibido todo tipo de transporte internacional de pasajeros.

En medio de este largo y estricto encierro, en abril del 2020, se dio un fenómeno de migración masiva para dejar la ciudad de Lima. Miles de personas decidieron irse caminando de regreso a sus pueblos de origen o a los de sus padres y abuelos. Fue un desafío masivo del estado de emergencia porque el confinamiento obligatorio para salvaguardar la salud por el virus no tenía sentido sin agua, comida, ni trabajo. Y el Estado peruano tenía poco que ofrecerles para retenerlos: se distribuyó en abril un primer bono llamado “yo me quedo en casa” (380 soles aproximadamente 120 dólares) para apoyar económicamente a las familias peruanas más pobres y en situación de trabajo informal o autoempleo. Era una medida paliativa en medio de la emergencia, pero la selección de los hogares beneficiarios y la distribución efectiva de los bonos tuvo enormes dificultades.

“Escaping from Lima” Photo by Rodrigo Abd, who won first place in the DRCLAS photo contest, “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America” with his series “The Virus Strips Peru.”

La ciudad de Lima, antes la promesa de mejores oportunidades, se tornó invivible durante la pandemia. Aquellos hogares sin servicios de agua ni desagüe, sin trabajo, sin seguro de salud, vieron en la migración hacia las provincias su única salvación. Un escenario desgarrador. Además, miles de estos caminantes fueron los antiguos migrantes (o inmigrantes) muchos desplazados forzados que vinieron en similares situaciones en décadas anteriores (o recientes) huyendo de la violencia, de la pobreza, de la falta de oportunidades. Las autoridades regionales tuvieron que gestionar buses para los traslados pero a su vez había recelo y temor que los caminantes trajeran el virus a las provincias, cuyas condiciones de salud son aún más precarias que en Lima. Tenemos el registro de 167 mil personas empadronadas para ser trasladados en buses; pero otros muchos se fueron caminando hasta sus pueblos.

Las calles, las plazas, los parques, las playas fueron estrictamente custodiadas por brigadas de policías y militares armados, y en algunas avenidas principales de Lima iban acompañadas por tanques de guerra que vigilaban el cumplimiento de las normas. Además, se dispuso el toque de queda entre las 8 p.m. y las 5 a.m., entre esas horas toda circulación estaba estrictamente prohibida, con excepción de las emergencias médicas.

En mi casa no se salía, ni a comprar. Todos los pedidos fueron a domicilio, pero como estos podían demorar semanas y había límites en algunos artículos (jabón, alcohol y papel higienico, harina) entonces había que pedir intercaladamente a distintos proveedores. La llegada del pedido suponía un estricto proceso de desinfección de todos y cada uno de los productos. Mis hijas estaban abrumadas con el aislamiento social y el súbito estudio a distancia — la menor en su último año de colegio y la mayor estaba en tercero de universidad— y aunque colaboraban en todo lo que podían, la mayor carga doméstica recayó en los adultos, que andábamos también sobrecargados con el trabajo a distancia. Imposible quejarse. Miles no tenían uno. La señal de internet colapsaba a menudo. Las pantallas abarcaban todo y las distintas plataformas virtuales definían todas las interacciones (reuniones de trabajo, dictado de clases, encuentro con amigas, conversaciones familiares, chats, terapias, entretenimiento, compras, todo), en una hiperconectividad salvadora y agotadora.

Este encierro a la peruana se prolongó por cuatro largos meses. El presidente Martín Vizcarra hacía anuncios diarios en la televisión donde informaba sobre la expansión del virus y las decisiones de políticas para frenar dicho avance. Así el aislamiento social obligatorio que empezó con 15 días de confinamiento se fue ampliando paulatinamente y al final fueron 120 días de severo encierro y aislamiento.

Lo cierto es que una vez “levantada” esta cuarentena se mantuvo la declaración de estado de emergencia a nivel nacional y por tanto, las restricciones y el toque de queda. El estado de emergencia fue finalmente levantado recién en todo el país el 31 de enero del 2022, es decir, más de 22 meses después de iniciada la cuarentena.

En una sociedad postconflicto como la peruana la declaración del estado de emergencia, la custodia de las calles por militares y el toque de queda son medidas que tienen historia. Por tanto, su sola mención evoca otras memorias de violencia, de terror, de caos y también de abusos por parte de las fuerzas del orden. Recuerdo mi sorpresa y desazón al escuchar que se había declarado el país en estado de emergencia. Y luego ver las avenidas principales de la capital con tanques y jóvenes soldados controlando la circulación de la ciudadanía—y arrestando a los infractores—fue una imagen muy perturbadora que lejos de darme calma o seguridad, me inquietaba, sin duda consecuencia de mis memorias la violencia política vivida en el país durante los años 80s y 90s.

El propio presidente de la república, Martín Vizcarra, hizo explicito el vínculo con nuestra historia de violencia y al poco tiempo se generalizó el uso del lenguaje bélico para enfrentar la pandemia: “No tengo la menor duda de que venceremos en esta guerra porque tenemos peruanos que cumplen su función y ustedes los representan. Defendieron a la patria cuando se les requirió, enfrentaron al terrorismo y están luchando contra otros enemigos, como son el narcotráfico y la delincuencia, pero hoy están al frente de otro enemigo silencioso” (El Peruano, 16 abril 2020).

El vínculo con el pasado se vivió también en la amenaza constante a la vida, en el sufrimiento para conseguir una cama o un balón de oxígeno, y la muerte misma sin despedida ni rito posible, que aparecía como un espejo del dolor y desasosiego que vivieron y viven miles de familias ante la violencia y a las que siguen buscando a sus familiares desaparecidos durante la década del 80 y 90. Para muchas familias, llovió sobre mojado: la partida prematura de familiares en manos de un “enemigo silencioso” no parecía una historia nueva sino más bien una recurrente pesadilla.

“Mass for the Dead” Photo by Rodrigo Abd, who won first place in the DRCLAS photo contest, “Documenting the Impact of Covid-19 through Photography: Collective Isolation in Latin America” with his series “The Virus Strips Peru.”

A este duelo nacional por las pérdidas de vidas humanas, por el incremento de la pobreza y por la vulnerabilidad de cientos de miles familias, se sumó una inestabilidad política sin precedentes. Durante la peor crisis de la pandemia (2020-2021) tuvimos tres presidentes, cinco ministros de salud, dos ministros de educación y un sin número de escándalos de corrupción, entre los que se encuentra el Vacunagate (el destape de la aplicación de vacunas chinas de forma irregular entre altas autoridades peruanas, en medio de la total escazes de vacunas para la población). En resumen, la pandemia se desarrolló en el marco de una tremenda crisis económica y política que se ha prolongado y a la que, a veces, parece que hemos quedado presos.

A esto se suma, que el Perú es uno de los países que más ha demorado en retomar las clases presenciales. A pesar del esfuerzo estatal por desarrollar en tiempo récord una plataforma de atención educativa remota (con el Programa Aprendo en Casa), cientos de miles de estudiantes vieron interrumpidos completamente sus estudios y la gran mayoría de estudiantes del país continuaron estudiando remotamente de modo precario y desigual, en particular los estudiantes en zonas rurales sin conectividad. Considerando que nuestro calendario académico va de marzo a diciembre, esto supone dos años completos sin asistir a las aulas para la mayoría de los niños, niñas, adolescentes y para todos aquellos que prosiguen estudios post secundarios. Los efectos de aquella privación no podemos dimensionarlo aún.

La experiencia de la pandemia en el Perú ha sido como un lente de aumento que ha mostrado lo peor y lo mejor de cada persona, familia, comunidad y del país en su conjunto. Sin duda ha habido enormes muestras de solidaridad, apoyo, y acompañamiento ante la carencia, la desesperación, el dolor y el abandono. Pero el balance es negativo, urge repasar críticamente lo vivido y hacernos cargo responsablemente nuestras carencias históricas como sociedad.

Francesca Uccelli is a Peruvian anthropologist and principal researcher at the Institute of Peruvian Studies. As a DRCLAS Custer Visiting Scholar (2021-22), she had the opportunity to spend two academic semesters widening her focus, revising her experiences and consolidating her previous work on education, youth, memory and the scars of the political violence of the 80’s and 90’s in Peru. Her project is to develop a theoretical-methodological framework for citizen formation and cooperation to confront intolerance, indifference, polarization and the simplistic and polarized views that characterize our daily interactions

Francesca Uccelli es antropóloga peruana e investigadora principal del Instituto de Estudios Peruanos-IEP. Como Investigadora Visitante Custer en DRCLAS (2021-22) tuvo la oportunidad de pasar dos semestres académicos ampliando enfoques, revisando experiencias y consolidando su trabajo previo sobre educación, juventud, memorias y secuelas de la violencia política vivida en los 80 y 90. Su proyecto es desarrollar un marco teórico-metodológico de formación ciudadana y convivencia que permita enfrentar la intolerancia, la indiferencia, la polarización y las miradas simplistas y maniqueas que caracterizan nuestra interacción cotidana.

Related Articles

Haiti: A Gangster’s Paradise

Haiti is in the news. In recent weeks, gangs have coordinated violent actions, taken to the streets and liberated thousands of inmates to spread chaos and solidify their control of the Port-au-Prince capital.

Crime and Punishment in the Americas

As 2024 ushered in, newly-elected Ecuadorian President Daniel Noboa issued a state of emergency in his country, citing a wave of gang violence spurred by the prison escape of a local criminal leader with ties to Mexico’s ruthless Sinaloa Cartel.

Women CEOs in Latin America: Overcoming obstacles, navigating through challenges

I first arrived in Latin America in 1997, and since then, I’ve been involved in education and the development of leadership and governance issues in the region. During these 27 years—12 of them from Spain—I have had the opportunity to interact with leaders from the region, the private and public sectors, multinationals and small and medium-sized enterprises, and various industries.