Mexican Immigration

The future of the United States will be in no small measure linked to the fortunes of a heterogeneous blend of relatively recent arrivals from Asia, the Caribbean, and, above all, Latin America first and foremost Mexicans.

The future of the United States will be in no small measure linked to the fortunes of a heterogeneous blend of relatively recent arrivals from Asia, the Caribbean, and, above all, Latin America first and foremost Mexicans.

The English language needs a new word for this extraordinary process of change in the Americas. I propose the neologism Latinization. Latinization is reshaping the character of the Americas. Indeed, it shall emerge as the most important vector in U.S. – Latin American relations bar none. Latinization, the product of globalization, is largely driven by the biggest migration flow in the history of the continent. I tentatively define Latinization as the processes of sociocultural, economic, and political hemispheric change traced to the experiences, travails, and fortunes of the Latin-American origin population of the United States.

Two social facts shape the contours of Latinization: (1) Latin America is in the midst of an unprecedented exodus; those leaving Latin America overwhelmingly choose the United States as their destination, and (2) the United States is undergoing a dramatic demographic transformation. New data make it plain that the United States is becoming a country where the white European-origin population is declining while the Latin American-origin population is growing exponentially. The Bureau of Census claims that in just two generations a full quarter of the U.S. population will be of Latino origin that is, nearly 100 million people will trace their ancestry to the Spanish speaking, Latin American, and Caribbean worlds.

At the dawn of the new century the 35 million-plus Latinos in the United States make up roughly 12 per cent of the total population. More Latinos than African Americans are currently attending U.S. schools. Indeed, Latinos may have already surpassed African Americans as the nation’s largest minority group (see Figure 1).

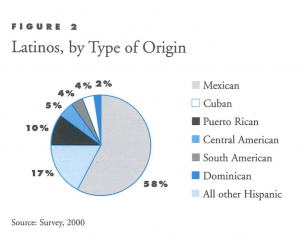

In this brief essay I offer some reflections on the most powerful force behind Latinization: Mexican immigration to the United States. There are now more than 20 million Mexican-Americans in the United States constituting 58 per cent of the Latino population (figure 2). They are at once among the oldest and newest Americans in the provincial rather than hemispheric meaning of the term. While the Mexican-American population goes back several centuries (after all there were Mexicans here before there was a U.S.) the majority of the Mexican-origin population of the United States is either immigrant or first generation U.S. born. Indeed, roughly seven million of them are Mexico-born. Today, in the midst of the largest wave of immigration in U.S. history, roughly one in four immigrants in the United States is a Mexican.

Large-scale immigration from Mexico, along with newer flows from Central America, South America, and the Caribbean, defines the tendencies of what U.S. scholars of immigration now call the new immigration. Three distinct social formations describe this new Latino immigration: (1) A more or less uninterrupted flow of large scale legal (as well as undocumented) immigration from Mexico, rapidly intensifying after 1980 (by the last decade of the Twentieth Century, there were more legal immigrants from Mexico alone than from all of the countries of Europe combined), structured by powerful economic forces and socio-cultural practices, which seem unaffected by unilateral policy initiatives, (2) more time-limited waves (as opposed to uninterrupted flows) of large scale immigration from Central and South Americably the early 1980s, El Salvador and Guatemala replaced Cuba as the largest source of asylum seekers from the Spanish-speaking world, and (3) a Caribbean pattern of intense circular migration typified by the Puerto Rican and Dominican experiences in New York where Dominicans are now the largest immigrant group.

Large-scale immigration from Mexico, along with newer flows from Central America, South America, and the Caribbean, defines the tendencies of what U.S. scholars of immigration now call the new immigration. Three distinct social formations describe this new Latino immigration: (1) A more or less uninterrupted flow of large scale legal (as well as undocumented) immigration from Mexico, rapidly intensifying after 1980 (by the last decade of the Twentieth Century, there were more legal immigrants from Mexico alone than from all of the countries of Europe combined), structured by powerful economic forces and socio-cultural practices, which seem unaffected by unilateral policy initiatives, (2) more time-limited waves (as opposed to uninterrupted flows) of large scale immigration from Central and South Americably the early 1980s, El Salvador and Guatemala replaced Cuba as the largest source of asylum seekers from the Spanish-speaking world, and (3) a Caribbean pattern of intense circular migration typified by the Puerto Rican and Dominican experiences in New York where Dominicans are now the largest immigrant group.

Mexican immigration to the United States is at once paradigmatic of a new globalized immigration system dominated by large numbers of peoples from the south moving to wealthier centers in the north and unique. The fact that Mexico lost roughly half of its northern territory to the U.S., the joint U.S.-Mexico border, the critical mass of Mexican citizens and Mexican-Americans now residing in the U.S. side of the line, and their heavy concentration in a handful of states, suggests a phenomenon that is quite distinct from other immigration to the United States. The large presence of undocumented Mexican immigrants (by some estimates nearly 40 percent of undocumented immigrants in the U.S. today are Mexicans) also separates their case from that of other immigrant groups though perhaps not from the experiences of Central Americans.

Over the last two decades, Mexican immigration to the United States has undergone significant transformations. Immigration scholars Wayne Cornelius, Jorge Durand, and others have noted that in the past, U.S. immigration policies, market forces, and the social practices of Mexican immigrants did not encourage their long-term integration into American society. A sojourner pattern of (largely) male-initiated, circular migration, seeking to earn dollars during a specific season, dominated the Mexican experience for decades into the 1980s. After concluding their seasonal work, large numbers of Mexicans typically headed south of the border and eventually started the cycle again the following year. In that context, Mexican immigrants engaged in dual lives, displaying the kinds of proto-transnational behaviors now more fully developed among Caribbean Latinos. Like Puerto Ricans and Dominicans today, the Mexican immigrants of yesterday lived here and there.

All of this has changed. Over the last two decades, new data suggest the intensification of a momentum to permanently settle in the U.S. side of the line. This can be explained in part by the maturation of the Mexican migration cycle. But it can also be explained by the intensification of the border control initiative at the U.S.-Mexican line. The current border control campaign, at an estimated two billion dollars the largest undertaking of its kind, ever, has resulted in large numbers of Mexican immigrants (especially those without papers) remaining in the United States rather than seasonally returning home. It has also made the crossings more costly, dangerous, and deadly as suggested by the deaths in the Arizona desert of 14 Mexican immigrants early in the summer of 2001.

Over time, Mexicans in the United States have become transnational citizens. They are emerging as important players in U.S. society while remaining powerful protagonists in the economic, political, and cultural spheres in the country they left behind. For every million people in the diaspora there are a billon dollars in remittances every year. This underscores the economic clout that the Mexican-origin population in the U.S. has in Mexico. Last year, the seven million Mexican citizens living in the United States remitted approximately seven billion dollars to Mexico. Politically, Mexicans in the U.S. are also becoming increasingly relevant actors with influence in political processes both here and there. Mexican politicians have recently discovered the political value of the more than seven million Mexican immigrants living in the United States. Mexican President Vicente Fox underscored a new official attitude towards expatriates when he toured the border region in December 2000 to personally welcome back a few of the estimated one million Mexicans traveling south for Christmas. The Mexican dual nationality initiative whereby Mexican immigrants who became nationalized U.S. citizens would retain a host of political and other rights in Mexico is also the product of this emerging transnational framework.

Three features characterize the new Mexican immigration to the United States. First, a growing body of research suggests that economic restructuring and the sociocultural changes taking place in the Americas virtually insure that Mexican immigration to the United States will be a long-term phenomenon. Globalization and economic restructuring have intensified inequality in Latin America, generating unemployment and underemployment, and with it new migratory pressures.

Second, in the U.S. side of “the line,” there is a voracious and enduring demand indeed, addiction might be a more appropriate term for Mexican immigrant workers in various sectors of the economy. The extraordinary Mexican-origin population growth in Nevada, Georgia, Arkansas, and North Carolina during the 1990s is tied to the explosion of new jobs in construction and service, meat, and poultry industries in those states. Although the extremely high flows of Mexican immigration to the United States during the last two decades will probably decrease eventually especially as Mexican fertility rates continue to sharply decline it is safe to assume that Mexicans will continue to dominate immigration to the United States over the next decades.

Third, new data suggest that the immigration momentum we are currently witnessing cannot be easily contained by unilateral policy initiatives such as the various border control efforts and theatrics that intensified over the last decade. Transnational labor recruiting networks, family reunification, and wage differentials continue to act as powerful contexts for Mexican immigration to the United States.

The Mexican presence in the U.S. is largely defined by immigration. The vast majority of Mexicans in the U.S. have been directly or indirectly touched by the experience of immigration. It is part of a shared experience and history that brings together the various distinct paths Mexicans have taken in their journey to the U.S. Although there have been differences in modes of incorporation and patterns of immigration, Mexicans in the United States share the experience of settling in this country and engaging in a process of social, economic, and cultural adaptation.

Fall 2001, Volume I, Number 1

Marcelo M. Suarez-Orozco is Victor S. Thomas Professor of Education at Harvard and a member of the DRCLAS Executive and Publications Committees. He is author of many books on immigration including Crossings: Mexican Immigration in Interdisciplinary Perspectives (1998) the inaugural volume in the DRCLAS Series on Latin American Studies, distributed by Harvard University Press, and Children of Immigration (Harvard University Press, 2001), co-authored with Carola Suarez-Orozco.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Mexico in Transition

You are holding in your hands the first issue of ReVista, formerly known as DRCLAS NEWS.

Over the last couple of years, DRCLAS NEWS has examined different Latin American themes in depth.

The View from Los Angeles

In 1999, on returning home to LA after four years at Harvard and in the Boston area,I ascended to the city of Angels for the annual gala dinner of the premier civil rights firm: the Mexican American…

What’s New about the “New” Mexico

On July 2, 2000, Mexican voters brought to an end seven decades of one-party authoritarian rule. Just over a year later, Mexico continues to feel the repercussions of this momentous victory…