Marcela Castillo is an ALB degree candidate at Harvard University, Division of Continuing Education, and she is currently in the special student program at the Harvard Graduate School of Arts and Sciences. After finishing her degree, she plans on attending Law School and pursuing a Ph.D. in Political Science.

My Experience in the 2018 Nicaraguan Student Movement

Paying the Price of our Troubled Past

As I search through my early childhood memories, I pause on my grandmother’s treasure chest. She stored all of our family photos here. My favorite has always been the picture of my dad and uncle in the Nicaraguan civil war. They were around sixteen years-old when they joined the fight against the contras, the U.S.-supported Nicaraguan counterrevolutionaries . At the time, I didn’t understand the nationwide pain that picture carried, but my young heart was proud of my dad’s courage and bravery.

I was raised Sandinista and took pride in my family’s ideals. Although I was too young to have any political or theoretical knowledge about the party, I knew Sandinismo—the philosophy of the group that overthrew the dictatorship of Anastasio Somoza in 1979— meant doing good for others, especially helping those in need. My grandmother was the only person in my family who spoke passionately about the revolution and civil war. It was rare for my dad to mention the war, and my uncle only started writing about it once he reached his forties. The sparkle in my grandmother’s eyes transcended her stories about the revolution and the freedom that came after the Somoza dynasty. That sparkle reignited my social justice ideals, represented by those of the Sandinistas. However, the suffering gaze that lingered when she spoke about her sons risking their lives in the war taught me that liberty’s price is unconscionable. Little did I know I would understand her pain from my own experience some years later.

The revolution’s illusion faded away as I grew up, but I kept on believing in social justice. The revolution promises of an egalitarian society were becoming a negotiated deal. What was being exchanged in the bargain was our liberty. And if I learned anything from my Nicaraguan history classes, it’s that the price of liberty has always been blood. In 2018, we, the students, paid that price for desperately wanting our freedom back. Some students paid with their lives, others were tortured, and some more privileged, like myself, were exiled.

The April Rebellion, as some Nicaraguan politicians call it, has a more profound and complicated explanation than the media narrative. Those blinded by pain fail to see that my generation carries a scar that has not been healed. We were born with an open wound that has widened over time as our parents taught us who were our enemies and who we had to hate. For those who belonged to the economic elites, the enemy was the resentful peasant or worker who sought to bring down the status quo. For those who were part of the poor majority, the enemy was the economic elites that resisted any threat that could strip away their exclusive political power. We were born confused, blaming our fellow countrymen and women for our misfortunes, but our greatest misfortune has been not being able to heal the wound of hate and inequality, which led us to innumerable wars and dictatorships. We have all been victims of power-hungry actors who use our anger and suffering as their campaign to hold on to that power.

In the context of this social inequality, rancor and pride context, Sandinismo returned to power in 2007, having been voted out in 1989. Sandinismo, beyond representing the revolution, represented the people, or so many saw it at the time. It represented the peasant or the street vendor who could not pay electricity bills or could barely afford his children’s food at the fortnight’s end. Ortega’s Sandinismo offered a dignified life and promised to bury the existing social barriers that have been around since Nicaragua’s independence.

Historically, social inequality in Nicaragua has been one of the worst in Latin America—the most unequal region in the world. In Nicaragua, wealth, land and power were unevenly distributed, with the economic elite keeping most of it while the rest lived in extreme poverty. This situation also created barriers that prevented the poor from accessing education, jobs or political representation. The Sandinistas promised a system that would offer everything the poor had always lacked, appealing to the poor and everyone who had been excluded from or discriminated against. The Sandinistas proposed a system where the people would no longer feel abandoned and a victim of an elitist state.

The hope of becoming an egalitarian society was what gave the Sandinistas their power to get their way. With help of some pacts in the National Assembly and a series of constitutional reforms, Ortega managed to conglomerate power in all branches of government. Over his last sixteen years in power, Ortega got absolute control over all institutions —the death of our democracy. He accomplished this by granting all government positions to people of confidence and reforming laws to fit his desires.

We were all silent observers of our democracy’s murder. We were scared of our troubled past and unwilling to spill more innocent blood. Moreover, Ortega was a career politician who knew how to negotiate with his enemies while keeping his supporters happy. The economic elite tolerated the Sandinistas by asking for favors in exchange for legitimizing their government. Meanwhile, most of the population enjoyed social reforms that had never been implemented before. To a certain extent, they received the political representation they never had.

As in the course of our history, the hostile silence we were facing would not last in the face of obvious abuses of power. After several years of accumulated anger, and suffering, Nicaragua, through the 2018 student movement, woke up. The rebellion started April 3, when a massive fire devastated more than 6.5 thousand acres of Indio Maiz in the northern region of Nicaragua—one of the largest wildlife reserves in Latin America. UCA (Universidad Americana) students and other protesters gathered outside UCA to protest the state’s institutional incapacity and unwillingness to extinguish the fire.

Two weeks later, after the Nicaraguan Legislative Assembly approved a law reforming social security (INSS) law, increasing employee taxes by up to 7% and reducing retirement pensions by 5%, the protests erupted. The INSS reforms mainly affected us, the students, because as college graduates in a highly unequal country, increasing taxes made rent unaffordable. On the other hand, the retirement pensions affected our grandparents, who could barely afford food prior to the reduction. Our indignation, however, resulted from the state’s maladministration of funds and the ramping corruption that forced them to reform INSS law. The student movement, far from being an organized structure before April 18, was born with frustrated self-convened students carrying our country’s history and pain.

On the afternoon of April 18, professors of the law faculty at the Universidad Americana (UAM) gave us permission to leave early to join the INSS protests in the mall area of Camino de Oriente near the university. Around 5 p.m., my mom called to drive me home when she heard the police were on their way to the protests, but it was too late. Some elderly protesters and other young professionals joined the demonstrations in Camino de Oriente. Not long after we arrived, the Sandinista youth group—La Juventud Sandinista—arrived with the protection of the police to repress protesters of all ages by beating them with metal tubes. I was lucky enough to find shelter in one of the restaurants nearby, but unfortunately, not everyone met the same fate.

The protests at UCA on the 18 told a different story. Students protested outside of the university and ran inside when the police arrived to restrain them, but the police forcefully entered the university to repress the students. Around 8 p.m., we heard a rumor that one of the students at UCA was shot and killed by the police. But by then, most of the universities in Managua, and the youth in other departments (states) were already protesting.

Countless youth were shot and severely injured on the night of April 18, 2018, in my homeland, Nicaragua. The next morning, the protests were no longer about INSS or Indio Maiz—we needed the governing duo of Ortega-Murillo out. The Polytechnic University of Nicaragua (UPOLI) and the National Autonomous University of Nicaragua (UNAN), turned into war zones where the police slaughtered students whose only weapons of self-defense were handmade mortars and rusty, old guns. Other students and youth built barricades forcing the private sector to close down the economy and the Sandinistas to step down. Churches became safe havens and refugee spots for injured protestors since hospitals were turning away. For the rest of April and through all of May, more than one million Nicaraguans took the streets of Managua, Esteli, Masaya, Leon and Matagalpa. In just four months, the Ortega-Murillo regime murdered more than 350 people and imprisoned more than 760 protesters.

International organizations and politicians denounced these crimes against humanity, but behind closed doors, they deemed us naïve. They criticized us for throwing ourselves into an impossible fight against the Ortega’s regime. But none of them were there, and they will never understand that once you see the blood of your friends on the streets, there is no turning back and to stop seeking justice and liberty is no longer an option. I told the same thing to my mom, when, crying desperately, she tried to stop me from going to the streets. But unlike those politicians, my mom understood, and packed my backpack with a rosary, some water, a small towel and vinegar, in case the police tossed tear gas bombs or bullets.

As I write about this moment in history that changed my life, and the lives of every Nicaraguan, I stare at my dad’s picture in the civil war and I truly understand his decision to risk his life for our freedom. But our fight was different, we didn’t have any arm or training. Our weapons were our bodies, our voices and some handmade mortars. They murdered, tortured, imprisoned and exiled us for screaming, “Justicia Para Nuestros Muertos” (Justice for Our Dead) and “Viva Nicaragua Libre” (Long Live Free Nicaragua) on the streets of our country. In 2018, I witnessed the Sandinistas, who once promised justice and freedom, commit the same crimes Somoza committed in the 70s. Our lives will never be the same, but this experience taught me that our democracy cannot be traded for a mere promise. For a democracy to function properly, it must represent the majority’s interest. But this cannot be a trade, because without liberty, there is no life.

Mi Experiencia en el Movimiento Estudiantil, Nicaragua 2018

El Precio de Nuestro pasado problematico

Por Marcela Castillo

Mientras busco en los recuerdos de mi niñez, vienen a mi mente todas nuestras fotos familiares que mi abuela guardaba como tesoro, en un cofre. Mi favorita siempre ha sido la foto de mi papá y mi tío en la guerra civil de Nicaragua. Tenían alrededor de dieciséis años cuando se unieron a la lucha contra los contra, los contrarevolucionarios Nicaraguenses respaldados por los Estados Unidos. En ese momento, yo no entendía el dolor nacional que conllevaba esa imagen, pero mi joven corazón estaba orgulloso del coraje y la valentía de mi padre.

Me criaron como sandinista y en ese momento, me enorgullecia de los ideales de mi familia. Aunque era demasiado joven para tener conocimiento político o teórico sobre el partido, sabía que el Sandinismo, la filosofía del grupo que derrocó la dictadura de Anastasio Somoza en 1979, significaba hacer el bien por los demás, especialmente ayudar a los necesitados. Mi abuela era la única persona de mi familia que hablaba apasionadamente sobre la revolución y la guerra civil. Era raro que mi papá mencionara la guerra, y mi tío, hasta que cumplió cuarenta años, comenzó a escribir sobre el tema. El brillo en los ojos de mi abuela, al contarnos sus historias sobre la revolución y la libertad que vino después de la dinastía Somoza, reavivó mis ideales de justicia social, que en ese momento los representaban los sandinistas. Sin embargo, la mirada de sufrimiento de mi abuela cuando hablaba de que sus hijos arriesgaron sus vidas en la guerra, me enseñó que el precio de la libertad es desmesurado. No me imaginaba que entendería su dolor por mi propia experiencia, algunos años después.

La ilusión de la revolución, se desvaneció a medida que fui creciendo, pero segui creyendo en la justicia social. Las promesas de la revolucion de una sociedad igualitaria se estaban conviertiendo en un trueque, sin embargo lo que se intercambiaba en ese trueque, era nuestra libertad. Y si algo aprendí de mis clases de historia de Nicaragua, es que el precio de la libertad siempre ha sido la sangre. En 2018, nosotros, los estudiantes, pagamos ese precio, por querer desesperadamente recuperar nuestra libertad. Algunos estudiantes pagaron con su vida, otros fueron torturados y algunos más privilegiados como yo, fueron exiliados.

La Rebelión de Abril, como la llaman algunos políticos nicaragüenses, tiene una explicación más profunda y complicada que el relato mediático. Los cegados por el dolor , fallan en ver que mi generación lleva una herida que no ha sido cicatrizada. Desde que nacimos, nuestros padres nos enseñaron quienes eran nuestros enemigos y a quien teníamos que odiar, lo cual hizo que esa herida abierta, se ensanchara con el tiempo. Para quienes pertenecían a las élites económicas, el enemigo era el campesino o el trabajador resentido que buscaba derribar el statu quo. Para quienes formaban parte de la mayoría pobre, el enemigo eran las élites económicas que resistían cualquier amenaza que pudiera arrebatarles su poder político exclusivo. Nacimos confundidos, culpando a nuestros compatriotas de nuestras desgracias, pero nuestra mayor desgracia ha sido no poder curar la herida del odio y la desigualdad, que nos llevó a innumerables guerras y dictaduras. Todos hemos sido víctimas de actores hambrientos de poder que utilizan nuestra ira y sufrimiento como campaña para aferrarse a ese poder.

En el contexto de desigualdad social, rencor y orgullo, el sandinismo volvió al poder en 2007, despues de haber salido del poder en las votaciones de 1989 . El sandinismo, más allá de representar a la revolución, representaba al pueblo, o eso consideraban muchos en aquellos tiempos. Representaba al campesino o al vendedor ambulante que no podía pagar las facturas de la luz o apenas podía pagar la comida de sus hijos al final de la quincena. El sandinismo de Ortega ofreció una vida digna y prometió enterrar las barreras sociales existentes desde la independencia de Nicaragua.

Históricamente, la desigualdad social en Nicaragua ha sido una de las peores de América Latina, la región más desigual del mundo. En Nicaragua, la riqueza, la tierra y el poder estaban desigualmente distribuidos, donde la élite económica se quedaba con la mayor parte mientras el resto vivía en la pobreza extrema. Esta situación también creó barreras que impidieron que los pobres accedieran a la educación, al trabajo y la representación política. Los sandinistas prometieron un sistema que ofrecería todo lo que siempre ha faltado a los pobres, apelando a los pobres ya todos los que habían sido excluidos o discriminados. Los sandinistas propusieron un sistema donde el pueblo ya no se sentiría abandonado y víctima de un estado elitista.

La esperanza de convertirnos en una sociedad igualitaria fue lo que entregó a los Sandinistas el poder conseguir lo que querian. Con ayuda de algunos pactos en la Asamblea Nacional y una serie de reformas constitucionales, Ortega logró conglomerar el poder en todos los poderes del Estado. Durante sus últimos dieciséis años en el poder, Ortega consiguió el control absoluto de todas las instituciones- la muerte de nuestra democracia. Logró esto otorgando todos los puestos gubernamentales a personas de confianza y reformando las leyes para que se adaptaran al gobierno que deseaba.

Todos fuimos observadores silenciosos del asesinato de nuestra democracia. Teníamos miedo de nuestro pasado problemático y no queríamos derramar más sangre inocente. Ademas, Ortega era un político de carrera que sabía cómo negociar con sus enemigos mientras mantenía contentos a sus seguidores. La élite económica toleró a los sandinistas pidiéndoles favores a cambio de legitimar su gobierno. Mientras tanto, la mayoría de la población disfrutó de reformas sociales que nunca antes se habían implementado. En cierta medida, recibieron la representación política que nunca tuvieron.

Como en el transcurso de nuestra historia, el silencio hostil al que nos enfrentábamos no duraría ante los evidentes abusos de poder. Después de varios años de rabia y sufrimiento acumulados, Nicaragua, a través del movimiento estudiantil en 2018, despertó. La rebelión estalló el 3 de abril, cuando un incendio masivo devastó más de 6,5 mil hectáreas de Indio Maíz en la región norte de Nicaragua, una de las reservas de vida silvestre más grandes de América Latina. Estudiantes de la UCA (Universidad Americana) y otros manifestantes se reunieron frente a la UCA , para protestar por la incapacidad institucional del estado y la falta de voluntad para mitigar el fuego.

Dos semanas después, después de que la Asamblea Nacional de Nicaragua aprobara una ley que reformaba la ley del seguro social (INSS), aumentando los impuestos de los empleados hasta un 7% y reduciendo las pensiones de jubilación en un 5%, estallaron las protestas. Las reformas del INSS nos afectaron principalmente a nosotros, los estudiantes, porque como graduados universitarios en un país altamente desigual, el aumento de los impuestos hizo que la renta fuera inasequible. Por otro lado, las pensiones de jubilación afectaron a nuestros abuelos, quienes apenas podían pagar la comida antes de la reducción. Nuestra indignación, sin embargo, se debió a la mala administración de fondos por parte del estado y la creciente corrupción que los obligó a reformar la ley del INSS. El movimiento estudiantil, lejos de ser una estructura organizada antes del 18 de abril, nació con estudiantes frustrados autoconvocados cargando la historia y el dolor de nuestro país.

En la tarde del 18 de abril, profesores de la facultad de derecho de la Universidad Americana (UAM) nos dieron permiso para salir temprano para unirnos a las protestas del INSS por el centro comercial en Camino de Oriente cerca de la universidad. Alrededor de las 5 p. m., mi mamá me llamo para llevarme a la casa cuando escucho que la policia se dirigia a las protestas, pero ya era demasiado tarde. Algunos protestantes de edad avanzada y otros jovenesprofesionales se unieron a las protestas en Camino de Oriente. Poco después de que los estudiantes llegáramos a manifestarnos al Camino de Oriente, llegaron grupos de jóvenes sandinistas (La Juventud Sandinista), con la protección de la policía para reprimir a los manifestantes de todas las edades golpeándolos con tubos de metal. Tuve la suerte de encontrar refugio en uno de los restaurantes cercanos, pero desafortunadamente no todos corrieron la misma suerte.

Las protestas en la UCA del día 18 de Abril del 2018, contaron una historia diferente. Los estudiantes protestaron afuera de la universidad y corrieron adentro cuando llegó la policía para detenerlos, pero la policía entró a la fuerza a la universidad para reprimir a los estudiantes. Alrededor de las 8:00 p.m. de esa misma noche, escuchamos el rumor de que uno de los estudiantes de la UCA fue asesinado a tiros por la policía. Pero para entonces, la mayoría de las Universidades de Managua y la juventud de otros departamentos (ciudades) ya estaban protestando.

Innumerables jóvenes fueron baleados y gravemente heridos la noche del 18 de abril de 2018 en mi país de origen, Nicaragua. A la mañana siguiente, las protestas ya no se trataban del INSS o el Indio Maíz, necesitábamos la salida de la pareja gobernante Ortega-Murillo. La Universidad Politecnica de Nicaragua (UPOLI) y la Universidad Autonoma de Nicaragua (UNAN), se conviertieron en zonas de guerra donde la policía masacró a estudiantes cuyas únicas armas de autodefensa eran morteros artesanales y viejas pistolas oxidadas. Otros estudiantes y jóvenes construyeron barricadas obligando al sector privado a cerrar la economía y a los sandinistas a renunciar. Las iglesias se convirtieron en refugios seguros y lugares de refugio para los manifestantes heridos desde que los hospitales se estaban retirando. Durante el resto de abril y todo mayo, más de un millón de nicaragüenses tomaron las calles de Managua, Estelí, Masaya, León y Matagalpa. En solo cuatro meses, el régimen Ortega-Murillo asesinó a más de 350 personas y encarceló a más de 760 manifestantes.

Organismos internacionales y políticos, denunciaron estos crímenes de lesa humanidad, pero a puertas cerradas, nos consideraron ingenuos. Nos criticaron por lanzarnos a una lucha imposible contra el régimen de Ortega. Pero ninguno de ellos estuvo allí, y nunca entenderán que una vez que ves la sangre de tus amigos en las calles, ya no hay vuelta atrás y dejar de buscar la justicia y la libertad, es la única opción. Lo mismo le dije a mi mamá, cuando llorando desesperadamente trató de impedirme salir a la calle. Pero a diferencia de esos políticos, mi mamá entendió y empacó mi mochila con un rosario, un poco de agua, una toalla pequeña y vinagre, por si lapolicía tiraba bombas lacrimógenas o balas.

Mientras escribo sobre este momento en la historia, que cambió mi vida y la vida de todos los Nicaragüenses, miro la foto de mi padre en la guerra civil y realmente entiendo su decisión de arriesgar su vida por nuestra libertad. Pero nuestra lucha fue diferente, no teníamos armas ni entrenamiento. Nuestras armas eran nuestros cuerpos, nuestras voces y algunos morteros hechos a mano. Nos asesinaron, torturaron, encarcelaron y exiliaron por gritar “Justicia Para Nuestros Muertos” y “Viva Nicaragua Libre” en las calles de nuestro país. En 2018, presencie como los sandinistas, que alguna vez prometieron justicia y libertad, cometer los mismos crímenes que cometió Somoza en los años 70. Nuestras vidas nunca serán las mismas, pero esta experiencia me enseñó que nuestra democracia no se puede cambiar por una mera promesa. Para que una democracia funcione correctamente, debe representar el interés de la mayoría. Pero esto no puede ser un intercambio, porque sin libertad no hay vida.

More Student Views

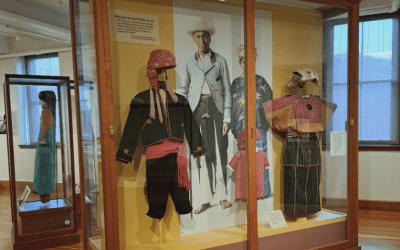

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Río Piedras: As a Desert Flower Blooms in the Night

The sunset of my first day at the Harvard Puerto Rico Winter Institute (HPRWI) painted the sky with violet and magenta. It felt as if the day had just begun.

Colombian Women Who Empower Dreams

English + Español

The verraquera of Colombian women knows no bounds. This was the message left with me by the March 30 symposium, “Empowering Dreams: 1st symposium in honor to Colombian women at Harvard.”