Navigating the Borders of Belonging

Seeking Refuge in Queer and Trans Oases across Latin America

Source: https://casaarcoiris.org/en/lgbt-asylum-at-the-border/

Despite pledging to end Title 42, the Trump-era law barring migrants from seeking asylum in the United States, the Biden administration recently enacted its own asylum ban through the “Circumvention of Lawful Pathways” rule. Under this policy, any migrant who has traveled through a third country en route to the southern U.S. border would not be eligible to apply for asylum. This would prevent people from countries other than Mexico from exercising their right to refuge under international, humanitarian and U.S. law. This decision comes as several Central American and Caribbean migrant caravans travel towards the United States. Fleeing violence, economic precarity and discrimination, among those most impacted are LGBTQ+ migrants, individuals whose identities and experiences have been criminalized in not only their countries of origin, but in their new—often temporary—homes as well.

In 2017, 11 transgender women and six cisgender gay men formed the “first Rainbow Caravan.” Seeking asylum in the United States, these LGBTQ+ migrants left Honduras, Guatemala, Nicaragua and El Salvador in hopes of finding protections based on their sexual orientations and gender identities. Since then, several Rainbow Caravans have marched near general caravans—which make up thousands of refugees—from Central America to the southern U.S. border. Proximity to the larger migrant groups has ensured safety in numbers during an often dangerous and difficult journey; however, an extra need for extra safety given some of the added barriers LGBTQ+ migrants encounter—even from members of the larger caravan—has required them to keep some physical distance from them throughout the journey. In other words, LGBTQ+ migrants face another unanticipated border that distinguishes them between their predominantly cisgendered (those who identify with the sex assigned to them at birth) and heterosexual counterparts in the larger caravans: fears of homophobic and transphobic violence.

Source: https://www.uusc.org/solidarity-and-shelter-for-lgbtq-immigrants/

For migrants, crossing borders is a regular phenomenon. However, the intersections that each migrant experiences complicates the quantity and severity of borders they must encounter. Black and Indigenous refugees, in particular, face more scrutiny from local officials regarding their perceived authorization. For LGBTQ+ migrants, minoritized expressions and stigmatized behaviors further alienates them. Those that speak an Indigenous language, Portuguese, Haitian Creole or another language other than Spanish result in barriers to communication with other migrants, let alone police officers at a migratory checkpoint.

Moreover, individuals with state identification not recognized by border enforcement for authorized entry face seemingly illicit means to cross into a new country. So, for instance, Black trans migrants from Haiti are forced to confront the borders of race, ethnicity, gender, sexuality, language and documentation (given different national laws around passport recognition) in addition to the physical and figurative borders that other members of the general caravan have to cross. Evidently, these borders add immense hardship to their already difficult journeys, largely due to additional criminality attributed to their sheer existence.

Regarding criminality, it is important to put into context how western influences—particularly from the United States—have heightened both the need for individuals to migrate and the persistent challenges they encounter once they begin their journeys. El Salvador, Mexico and Brazil currently have among the highest rates of femicide and murders of LGBTQ+ people. However, these attitudes about gender and sexuality are not homegrown issues. Instead, they exist because of colonization. The Americas have thousands of years of traditions that embraced trans and queer experiences and identities. However, upon arrival, European powers criminalized these behaviors. One of the earliest instances was in 1518, during which conquistadores staged a brutal, public execution 40 two-spirit individuals of the Quarequa community in what is now Panama.

With growing Catholic values across the region, colonization cemented the cis-heteropatriarchal values prevalent today. And, despite Panama, Costa Rica and Mexico having legalized marriage equality (the latter two before the United States), efforts to promote queer-antagonistic messages across Central America have significantly increased in recent years. Since 2015 various U.S.-based evangelical groups created, funded, and expanded campaigns promoting the nuclear family after the Supreme Court of the United States enshrined marriage equality; such efforts grew exponentially since the Trump administration. Evidently, widespread campaigns demonizing queer and trans people elevate the potential for violence they may be subject to, ultimately displacing them from their homeland in search of safety elsewhere.

Source: https://www.nbcnews.com/news/latino/dream-come-true-lgbtq-couples-migrant-caravan-marry-seeking-asylum-n938051

In addition to worsening conditions for LGBTQ+ individuals across Central America, the United States has also exported its “crimmigration” practices and policies to the region as well. Mexico’s southern border—particularly with Guatemala—has been dangerous for decades. Border enforcement personnel line the Río Suchiate that separates the two countries, while supposedly random checkpoints are found across the southern states, a site that eerily mirrors that of the southern U.S. border. More recently, however, Guatemala’s border has also been militarized, with police blocking the road and threatening the caravans. Such practices are migrating south, with El Salvador and Honduras also militarizing their respective borders, and with the US opening various detention centers from Mexico down to Colombia.

As border enforcement extends further south, LGBTQ+ migrants are placed in increasingly precarious situations. Coupled with the Biden administration’s ban on asylum, LGBTQ+ migrants risk remaining in dangerous settings. Ciudad Juárez, one of the largest entry points into the United States, is infamous for its femicides, and for transwomen, that number is much higher. In El Salvador, where the president has run his own discriminatory campaign against queer and trans people, denial of entry into Guatemala could prevent migrants from escaping a hostile environment. According to Al Otro Lado, a Tijuana-based advocacy group for migrants, refugees, and deportees, one in four LGBTQ+ migrants they interviewed reported being survivors of sexual assault, while one in five described encounters that involved kidnapping. As such, detention on the other side of a border could be fatal.

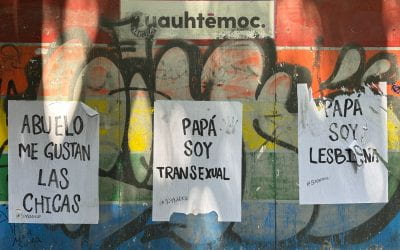

Efforts to militarize the border and extend it south are not the only hindrances to seeking asylum in the United States; another barrier to entry is the rampant rise in anti-LGBTQ+ policies in various states. Nationwide, state legislatures are actively stripping rights to bodily autonomy, severely limiting reproductive rights as well as gender-affirming care for individuals and communities that depending on such vital healthcare procedures. Bans on LGBTQ+ themed books and curricula coupled with restrictions on drag shows and gender diverse expressions via clothing in public spaces further criminalize already vulnerable communities. Well aware of these issues and navigating the new asylum ban, LGBTQ+ migrants from Latin America must think long and hard about which region may be the safest for their own personal safety and well-being. While the United States is still appealing for many, an increasing number have opted to remain in Latin America to find sanctuary.

One common destination for LGBTQ+ migrants is Brazil, the country that consistently holds the largest pride parades in the world. Brazil, and especially São Paulo and Río de Janeiro, has a long history of welcoming LGBTQ+ people, making it an appealing space for migrants. Though the previous administration did enact its own share of policies that heightened discrimination for queer and trans people and restricted migration, the Lula administration appears to be reversing some of those policies. Another major destination is Mexico, where more than 20,000 LGBTQ+ migrants have applied for asylum this year alone. A longtime magnet for queer and trans Mexicans, Mexico City has seen a significant rise in Central American migrants seeking refuge over the last decade. One reason for the rise in LGBTQ+ asylum applications is because many who are denied from even applying to the United States elect to stay in Mexico. This, coupled with a growing number of LGBTQ+-centered shelters and migrant advocacy organizations across the country, such as Casa Arcoíris and Casa de Luz in Tijuana, make this third country a viable option.

MIGUEL GUTIERREZ/AFP/Getty Images)

Beyond these two countries, various oases for LGBTQ+ migrants exist across Central America as well. In Guatemala, for example, la Casa de la Cultura LGBTIQ 4 de Noviembre promotes LGBTQ+ visibility and culture within the country’s capital, a similar mission as the la Asociación LGTB de Honduras. Likewise, Nicaragua’s Managua-based Fundación Xochiquetzal and El Salvador’s Diké both focus on health education and advocacy for the community. These organizations may be one of a few in their contexts that focus on LGBTQ+ issues, but all four see hundreds of locals and migrants each month. These oases provide hope for LGBTQ+ Latin Americans and contribute to growing communities and acceptance in each of these contexts.

Michael Ángel Vázquez is a fifth-year Ph.D. student at Harvard in Education whose research projects focus on Ethnic Studies, Migration, and LGBTQ+ narratives.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.