Option Colombia

While many Colombians are desperate to escape the bombings and kidnappings that have ripped into daily life here, others want to stay, roll up their sleeves and make a difference.

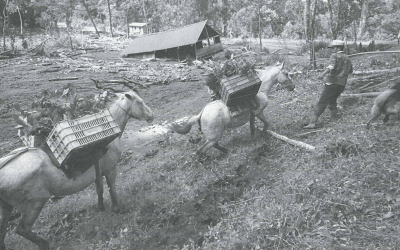

At least this is the case for more than 3,000 college students volunteering for “Option Colombia,” a Peace Corps-style program that for 10 years has sent students to communities all over the country peaceful or in conflict, poor or prosperous, tucked into deep jungle or perched in the rugged Andean mountains.

This effort continues while Colombians, especially well-educated ones, leave at record rates because of skyrocketing kidnapping rates, high unemployment and escalating violence.

But this is not the case for Enrique Chaux, who was a physics student at Bogota’s University of Los Andes with his mind set on a natural sciences career when he went to work as a volunteer in Vigia del Fuerte, an isolated town near Colombia’s tropical Pacific Coast inhabited mostly by descendants of slaves and Embera and Cuna native Colombians.

He arrived in this rainy town in 1994, just after a deadly earthquake with the mission of supervising reconstruction projects. But he soon realized he had walked into a life-changing experience, in a place so remote and forgotten that a police inspector once asked him what had happened with the plans to send a man to the moon.

He had also entered a hive of corruption. He learned that on paper the government was supposed to be reconstructing 12 schools, but nine of them had never existed. In addition, resources were being plundered and several projects were underway that the community did not need.

Chaux, 34, says his job as watchdog of public spending was complicated by the suspicion that most of the town’s gasoline–essential for travel on the river that is the town’s main artery–was ending up with the guerrillas. The numbers didn’t add up and the people felt that it was difficult to change things.

“After I came back to Bogota I was empowered, I felt that there was a lot to do but that I could contribute to it” said Chaux, who finished his doctorate in Education with emphasis on violence prevention at the Harvard Graduate School of Education last year.

He said his Option Colombia experiences convinced him to shift the direction of his life from neuroscience to community work. Now he works as professor and researcher for an education research center at Bogotá’s University of Los Andes.

As with all volunteer experiences, it’s hard to evaluate how much good-willed students leave behind on a permanent basis. Volunteer experiences can sometimes be plagued by amateurism, culture gaps and shock, and the inability to really make a difference over time. Option Colombia director, 25-year-old David Llanos, points out that there’s a lot of technology transfer by volunteers, although it doesn’t always have “sustainable impact” after the volunteer leaves.

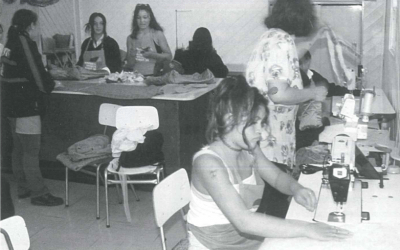

About 4,810 computers have been installed in almost 500 schools throughout Colombia. The program accepts donations of old computers, revamps them and installs them at impoverished schools across the country.

Beyond technology, student volunteers have made differences on a lasting basis. One of Option Colombia’s founders, Juanita León, who was a law student during her stint on Colombia’s Atlantic Coast islands, drew up immigration laws to regulate population flow to San Andres and Providencia. The law, which impedes overpopulation, is still in effect today. Likewise, a group of art students revolutionized the marketing of hammocks from the town of San Jacinto in the south of Bolivar State by doing a study on new colors and teaching the community the use of new pigments.

Yet, as Llanos readily admits, “After ten years of existence, Option Colombia has made some important contributions in some towns. But more than anything else, it is the students who have changed, who have fallen in love with communitarian work…and whether they pursue community action or corporate careers–even with multinationals–they have sown in them forever the love of working with the common people.”

Today’s volunteers sometimes find themselves in touch with the violence that many urban Colombians only see on television.

Engineering student Erica Prieto, who returned in December from her placement in Almaguer, a beautiful colonial town high in the southern Andes, experienced an attack by a division of the FARC, the biggest rebel group of the country. The group launched its seventh attack on the town while Erica was there, bombing a police outpost and several homes nearby.

“I came back with different feelings, on the one hand every time I hear a strange noise, my knees start shaking fearing another attack,” said Erica. “But on the other hand I learned to love Colombia more because I got to know it better, in its good and its bad side.”

Working with the program “Computers to Educate,” run by the presidency, Erica also faced many daily challenges. She had the computers, but many of the outlying villages don’t have electricity and had to be equipped with generators.

She also supervised public works in the schools helped educate teachers, students and even parents about the new possibilities that technology can bring.

Erica said she found it rewarding to see the people working together to safeguard their new computers, after feeling initially a very passive environment. But she also felt moved by the gifts of passion fruits from peasant mothers, thank-you notes and the feeling of making a small difference. She now says her heart–and probably her future–is now working with people, trying to improve the lives of others.

WHAT THE EMPLOYERS SAY

Students say it’s an incredible opportunity to satisfy a burning desire to make changes, to do something for the country, to live with different cultures, to leave their parents’ home for perhaps the first time even to earn money. But Option Colombia employers love their work.

Maria Isabel Mejia, the director of “Computers to Educate” says these students fit perfectly with the program’s need to accompany computers to their destination towns and provide training.

“The combination of the knowledge, enthusiasm and the desire to go to any place makes them a fundamental part of the program,” said Mejia, whose project is now the biggest employer of optionists. More than 200 students are scheduled to be hired by this program in 2002.

HOW IT ALL STARTED

Ten years ago, while drug lord Pablo Escobar was setting off bombs all over Colombia as part of his campaign to avoid extradition, a group of students, mostly from the University of Los Andes, founded Option Colombia.

“We didn’t want anything revolutionary,” said León, who is now a journalist. “We felt that more than changing the world, we wanted to change ourselves.”

She was one of the founding group of about 13 people, tired of the violence but with no pretension that they knew the solution to all the problems.

“The purpose was more humble,” said Leon. They wanted the university to come closer to the towns and narrow the gap between academic theory and reality.

Also, the group wanted to help strengthen the new 1991 constitution’s incipient decentralization process by helping transfer the technology skills and knowledge that advanced students had.

But more than anything, they wanted to do something that would make them happy, that would liberate them from the feeling that they were in a privileged bubble and even the fear of becoming bureaucrats or yuppies.

That’s when, in 1991, they created the Option Colombia Corporation, which is still managed by students. The corporation provides both the government and non-governmental organizations with college students willing to work anywhere for twice the minimum wage (around U.S. $ 300).

The idea started spreading and little by little groups of students all over the country promoted it in their own universities. Ever since, between 300 and 400 students have gone each year to small communities all over Colombia.

Other programs were born from this. The most important of all has been Option Latin America, supported by the Organization of America States, which has helped create national chapters in Chile, Nicaragua, Ecuador, Bolivia and Mexico.

About 50 optionists have gone to these countries to try to recreate the program, inspired by the dream of unified Latin America, and 15 other Latin Americans have come to Colombia. The program would love to include volunteers from all over the world.

But the program remains strongest in Colombia–because that’s where it started and perhaps because of the passion and idealism that the country’s crisis provokes in some. However, the ever-pressing realities of an escalating conflict are proving an obstacle, even though the desire to go to the countryside, to the jungles, to the little towns near the sea keeps motivating the students.

“Now we have to have meetings with their parents to let them know where their children are going and often there are tough questions about security that we don’t have answers for,” says Option Colombia director Llanos. However, he adds that no volunteers have encountered serious problems on that score.

The program also faces other issues, including its own success. Several universities now offer their own possibilities for a practical semester in the countryside, so employers can deal directly with them.

The 10-year review of Option Colombia concluded that people who have gone through this experience are more likely to be more socially responsible, remaining engaged in outreach programs and voting more, for example.

“If it weren’t for this experience, important human capital contributing to the country wouldn’t be doing it, because the potential these people had inside them would have been squelched,” says Chaux.

“Once you know your country from the inside, its cultures, its nature, you cannot abandon it.”

Spring 2002, Volume I, Number 3

Margarita Martinez is a Bogota-based writer who works for the Associated Press. A graduate of Columbia Graduate School of Journalism, she has learned first-hand how experiencing different countries and regions changes one’s perspective. Colombians and foreigners who wish to change their perspective by volunteering for Opción Colombia can find out more at or e-mail, attention David Llanos, executive director.

Related Articles

Obras de Infraestructura Básica de Fácil Ejecución a través de la Autogestión

En el Ecuador rural y en las zonas citadinas marginales, la carencia de servicios básicos se ha convertido en un mal endémico no resuelto hasta …

Responsabilidad Social Empresarial: Algunos Hechos Que Cuentan

La Responsabilidad Social Corporativa (RSC) es una temática más bien nueva en Chile. Aún cuando se encuentran acciones filantrópicas desde tiempos de la colonia, la relación de la …

Algunos Casos en Chile

Un caso fue José Tomás Urmeneta, un empresario del siglo XIX quien, en un momento de auge del sector agroexportador chileno, en su testamento dejó asignados recursos para …