Patsa Puqun

Ritual and Climate Change in the Andes

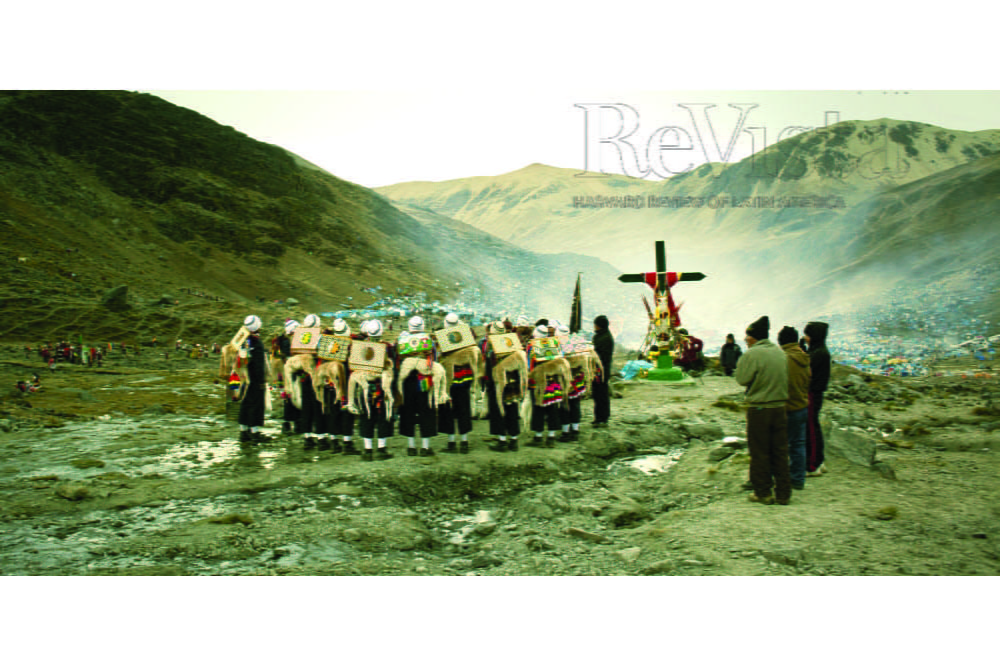

UKHUS, Dance troupe of “bears” with symbolic llamas, preparing to hike to the glacier in Ausangate, Peru, 2012. Photo by Central Regional Para La Salvaguardia Del Patrimonio Cultural Inmaterial De America.

It was a chilly predawn morning in 1984. I enthusiastically joined my Quechua-speaking host family going to their field at the base of one of Peru’s highest glacial mountains, Hualcan, to plant oca, a variety of native Andean tuber that produces at elevations over 10,000 feet. We turned the bend of a steep southeast-facing hill and were suddenly confronted with the majestic snowy peak.

Family members dropped their loads of tools and provisions, taking deep breaths of rarefied mountain air before squatting or sitting at this resting place, called hamana, a ritual point along a direct sightline to the glacier. “This will help you acclimate,” Don Antonio said, as he handed me a wad of coca leaves, while his wife served him a small gourd of fermented maize beer, spilling a bit on the ground in devotion to the earth. Doña Francisca motioned for me to rest on an accommodating rock as the sun rose from behind the mountain.

Just then, bright sunlight reflected off the metal tools and a shiny adornment on Don Antonio’s wrist—it was a watch, an item only recently affordable to the general population. Curious, I inquired, “What time is it?” Don Antonio first looked up toward the position of the sun, then looked at his watch, finally he turned to me and said, “Inti hatunnam,” which means, “the sun is [getting] big.” As the sun cycles through the sky, he is considered “to grow larger” until midday, after which he begins to shrink as he travels along his route toward the western horizon. Another time, when I asked an older villager when would be a convenient time to visit her, she thought a moment and replied, “Inti ichikllam,” meaning when the sun is tiny and low in the sky, referring to sundown.

Time and seasons are very important in Andean culture. A major aspect of Andean seasonal fiestas is a ritual harvesting of the glacial ice. People from the lowlands put the ice in their soups and drinks in celebration of the community relationships with the high mountain deities that provide essential water for crops. This special kind of ice is considered medicinal, categorized as “hot and dry” and applied to ailments caused by cold and wet elements. Ceremonial ice harvest is a focal point of the largest pilgrimage on the South American continent, Quyllur Rit’i (“star snow”). This celebration draws tens of thousands of believers every year on the full moon prior to the June Solstice in the southern Cuzco region, to the mountain Qolqepunku (literally, “storehouse door,” in reference to the star that leads the constellation Pleiades observed from that perspective at that moment in time). However, as the glaciers recede, not only is it more difficult to reach the ice, but touching, harvesting and dancing on the ice is now prohibited. This limitation causes troupes of dancers, worshippers, and musicians to continue to fulfill their spiritual obligations, but now at the place where the glacier once existed.

In the Callejón de Huaylas, consumption and appreciation of ice still goes on, but differently. An elderly ice harvester, Sr. Teodoro, has made the provincial town of Carhuaz famous for ice cream flavored with seasonal native fruit. He tells us, “We would leave the house around 3 a.m. to reach the ice before dawn. At the high lake, Shonquil, we would place our chewed coca leaves to appease the mountain, and quickly approach the glacier. This is the most dangerous moment. You must be sure of yourself and know how to relate with the mountain, or you may be killed or later become very ill and die. It is important to work fast, you must cut the ice, tie it to your back and then run down the mountain at top speed without looking back. I would rush home and by 10 a.m. we would be serving flavored shaved ice in the plaza for the Fiesta de Mamá Meche (Celebration of the Virgen de las Mercedes, patron saint of Carhuaz at September Equinox).”

Communities in the Quebrada Hualcan manage communally owned land all the way up to the glacier, and may still permit ice harvesting for ritual and medicinal purposes by community members only. On my visit to communal pasturelands more than 12,000 feet with retired ice harvester, Don Eulogio, he pointed out the place on the dark rocky mountainside where the glacier once reached. He expressed sadness as he remembered his experiences of receiving the ice as a gift from the mountain to the people as a sign of mutual care and respect between the environment and inhabitants. Our team specialist in Quechua language, knowledge, and concepts, Martín León Huarac, says that local farmers explain climate change in terms of patsa puqun, a notion that the earth is in an advanced stage of maturity, perhaps even fermentation, hence the warming of the high altitude ecological zones that affect agropastoral activities.

Andeans do not conceptualize astral and seasonal processes to cycle inevitably and effortlessly, but consider rather that purposeful human activity, in forms of ritual actions and responsible work, must take place to guide and ensure desired outputs of human-environment relationships. Patsa, as time-space, may be verbalized as patsaakaatsiy: adaptation and acclimatization of humans and plants to changing environmental conditions. Puquy refers to ripening, but maturation has its peak expression of suitable ripeness, after which fermentation and/or spoiling commences that may lead to rotting, rather than the desired cycle when fruits of harvest return to seed to bring new life.

For the Andes region of South America, time-space concepts as explained by Inca elites continue to be deeply embedded in the cosmovision of present-day Quechua-speaking peoples. The interactions between human beings and their environment weigh heavily in interpreting the world and society in which we live. Thus, a changing climate has a profound effect on the thinking and actions of the inhabitants of the Andes (see Murra, J. El “control vertical” de un máximo de pisos ecológicos en la economía de las sociedades andinas. Visita de la Provincia de León de Huánuco en 1562. [Huanuco, Perú: Univ. Nac. Hermilio Valdizán]).

The dramatic mountain landscape of the glacial ranges of the Andes is central to highland livelihood and social organization where communities manage dispersed agricultural plots at distinct altitudes with particular ecological characteristics. Peru has an enormous agrobiodiversity that has contributed more domesticated edible plant species to the human diet worldwide than any other region. Therefore, the effects of climate change on food security are important to its habitats and crop experimentation.

Time in Andean thought is cyclical, entwined with both biological and social processes that give form and meaning to concepts of chronology and appropriate moments for human action. Humans and nature are merged in consequential relationships in which rituals are means of communication and reciprocation. Life processes are applied to describe annual seasons and significant eras, as comprehended in the use of the Quechua terms patsa and puquy.

RITUAL AND CLIMATE CHANGE

Our Center for Social Well Being in the Hualcan valley (Quebrada Hualcan) of the Cordillera Blanca explores issues of climate change here in the highest tropical range on the planet, where the glaciers are a storehouse for a significant reserve of fresh water. We work with traditional Quechua communities— as well as with researchers from a wide array of disciplines such as glaciology, geography, environmental studies, public health and anthropology. The center’s indigenous experts note that the term patsa puqun came into use with the current era of global climate and culture change. While patsa (equivalent to pacha in Cuzco Quechua) is often translated as “earth,” it actually refers to a combined concept of time-space, or the world in which we live. The verb puquy—to mature or ripen—refers to agriculture, humans, and the fermentation of grains. In the yearly agricultural cycle, puquy is a season that commences with the December solstice, when plants sprout. Then, plenty of rainfall should continue up until the month known as patsa puqu quilla in pre-Spanish times (the present March equinox) and harvest celebrations, now merged with Christian Carnival and Easter traditions.

We must dispel the myth that indigenous peoples are unaware of climate change and its implications, a belief held by academics, scientists and others who influence government decisions with regard to water and land use. On the contrary, contemporary Quechua communities that interact daily with their environment are not only highly sensitive to and observant of ecological erosion and transition, but are key actors in the development of viable sustainable adaptation and mitigation strategies, to which they bring thousands of years of wise experience, continually acting in response to the consequences of global climate and culture change as lived in the Andes.

Spring 2014, Volume XIII, Number 3

Patricia J. Hammer is the director of the Center for Social Well Being-Peru. She is a medical anthropologist (University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign) with more than twenty years of research and field experience in Peru and Bolivia.

Related Articles

Festival and Massacre

Festivals are privileged spaces to help us understand the meaning of community. They are a special way of presenting historical narratives, bringing…

Fiesta and Identity

English + Español

In Barranquilla the days of Carnival begin early. From the first hours of the day—already confused with the last hours of the night—the smells of celebration are in the air. The streets…

Fiestas: Editor’s Letter

At the Oruro Carnival, a few hours from La Paz, the heavy-set blue-skirted women swirl past me in a dizzying burst of color and enviable grace. The trumpeters, some with exotically dyed hair, blare not too far behind. I remember that as a young man President Evo Morales had been a trumpeter in this very carnival.