Preserving African and Afro-Brazilian memory

In Brazil, little has been done to preserve the memory of the conflicts and daily life of the Afro-Brazilian population—its intangible heritage. Few museums, galleries, archives and documentation centers exist, and those that do are in poor condition. Large institutions that should perform that function—above all the National Library (BN) and the National Archive (AN)—do not see the preservation of this heritage as a priority.

The project for a Digital Museum of African and Afro-Brazilian Memory aims to raise the awareness of these institutions, by getting them to address among their priorities the “Black issue,” meaning race relations, racism and Afro-Brazilian culture. This entails reviewing their collections and changing their indexing systems to include terms such as race or color, racism, Negro, Afro-Brazilian and Africa. Finally, priority must be given to those topics in their exhibitions and publications.

Our Digital Museum began as a digital version of an anthropological archive and was, therefore, initially called the Digital Archive of Afro-Bahian Studies. As it developed, it incorporated historians, curators and library scientists into its team and network. The term “African” was included in the name to reflect the establishment of a series of exchanges with African archives and museums. The museum is a network of five stations in Brazil and one in Portugal that function in relative independence from each other and are based at the Federal University of Bahia,which started the project, and the Federal University of Pernambuco, the Federal University of Maranhao, the State University of Rio de Janeiro the Federal University of Rio Grande do Norte) and the University of Coimbra in Portugal. It is worth stressing that the first access to our stations occurs largely via our Facebook pages.

The Digital Museum deals with race relations and racism. The testimony of both Blacks and whites will be as important as records found in documents, processes or newspapers. To place racism into the context of a museum, even a digital one, naturally demands that we reflect on what it means to contemplate pain and evil. Therefore, reflections on the Holocaust and slavery, and apartheid museums are a source of inspiration. Although it can be difficult and painful to recall the time of slavery, particularly when it has left its long-lasting mark in contemporary inequalities such as racial discrimination that still affects most of the population, it is now positively necessary to do so.

The federal law of 2003 that demands the teaching of African and Afro-Brazilian cultures as a part of the social sciences cannot be implemented effectively without the preservation of collections of documents, visual images of all sorts and audiovisual materials including interviews with Black mães/pais-de-santo—who are the priestesses and priests of Afro-Brazilian religions— activists, politicians and intellectuals; or sound recordings of samba de roda groups, congadas, ternos de reis and other groups.

New communication technologies have a profound impact on the construction of collective memory and its relationship with the process of identity as well as in the development of heritage infrastructure. They have produced a new visual culture, which has benefited from the print-to-online transition of news and that of photography from film to digital image— resulting in a proliferation of user-friendly resources for making online filmed self-portraits and visual (auto)biographies through platforms such as YouTube, Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp. I dare say most contemporary Afro-Brazilian cultural traditions and, of course, music genres are now generously represented on social networks.

Digitalization also affects identity politics since digital and online archives have a considerable impact, not only on the politics of storage of documentation, but also on the politics of the past, memory and the future of traditions. The key issue is identifying the giving and receiving end in this process, or who retains the original document and who receives the digital copy. Different points of view emerge, such as those of local and visiting scholars, archivists, funders and virtual and ordinary visitors to the archive.

In general, the archivist community is largely concerned with conservation, while the research community with access and circulation. I do not believe digital technology to be the solution; however, without any doubt, it provides a new context and offers new possibilities. The digital medium is a means, not an end in itself. More than an antidote, the internet reflects inequalities. It makes them clear for others to observe and interpret. Information passed via digital media, in its quantity and organization—or disorganization—indicates that knowing how to choose defines one of the principal characteristics of the new intellectual elite. Although virtual or digital museums should not be viewed as substitutes for physical museums, and digital and physical visits—or tactile and digital experiences—should be viewed as complementary, one has to be aware of the irony by which digital museums, and intangible heritage, seem in some way to be the “solution” to the historic lack of museums in the Global South. It is the Global North that focuses more on tangible heritage and physical musealization.

The Digital Museum project considers these changes in communication technologies and the new set of tensions arising in the field of copyrights, authorship and privacy. It works by a code of conduct that safeguards the individual’s right to images while realizing the need to exhibit them and to listen to recordings and read texts produced by Blacks. How do we cope with the new tensions that result from the process by which certain cultural forms, finally ‘discovered’ and, at times, defined as intangible heritage, pass suddenly from invisibility to hyper-visibility, such as when, for example, a hitherto very “local” samba de roda group is introduced to play in the media spotlight (samba de roda is a genre of samba recently registered on the list of intangible heritage maintained by the IPHAN, the Brazilian Federal Heritage Foundation.

We want to be a “museum without owners.” The documents can be used freely for educational and research purposes; it is sufficient to cite the original text and our Digital Museum. Our collection is as much “inherited” from already extant archives as it has been created from scratch through new research and document acquisition. Inheritance of documents refers to the digital copy recuperation process, total or partial, from collections already pre- sent in the archives—copies that we can exhibit in themed galleries composed of documents from various archives. To describe what is involved in the creation of our collection, it is useful to refer to four policy concepts that guide our work.

Digital repatriation

We suggest to foreign archives that they continue to conserve original documents. However, we urge them to be altruistic with the digital copies, which we believe should be circulated freely without any significant cost of reproduction, permitting researchers to analyze documents without necessarily having to interrupt their work to travel abroad.

Digital donation

We intend to inspire a policy and practice of making documents available that were previously difficult or impossible to access. We aim to achieve this through our homepage, via an already available digital transfer tool, and indicating the National Library as a digital repository. We do not wish to retain original documents or items. Rather, we seek only to digitize, archive and display them as museum pieces in our virtual galleries. The originals will be returned to their owners. In certain cases, especially when there is a risk that original documents might be lost or suffer damage, perhaps through poor earlier preservation or because they might be sold abroad or lost to private collections, retention of such items can be mandated within an archive or public library as documents of public interest, to avoid their being sent abroad—as often happened in the past—and to facilitate the sourcing of resources for proper conservation.

Digital ethnography

That is, doing research in the field by means of a mobile digital scanning station and, later, a sort of traveling digital museum gallery, permanently under development and never seeming to be complete, searching out its audience and creating moments of drama such as the memories of slavery in the Bahian Recôncavo.

Digital generosity

Hypertext is already penetrating our research practices and the daily exchange of opinions between colleagues. Few bother to save their emails, which are frequently grammatically imperfect and full of jargon, invented terms and dialect. Conversely, in its exploration of new methodological frontiers, the internet could become a great new way to share research experience. Learning to share secondary data—and primary data when possible—suggestions, tips, questions, answers and annotations is all possible through the internet. A prototype portal has been developed through which researchers can exchange their experiences within a sort of chat room inside our Digital Museum; collective curatorship benefits from the opportunities created by the internet for new forms of crowd sharing and crowd-sourcing. With respect to copyright, we believe in the philosophy that guides the Creative Commons movement; citation is necessary, but payment is not.

We began the museum with a series of collections featured in the United States and France. Until then, the collections had not been available to a wide Brazilian audience because they were either not digitized or were unavailable online. The virtual ‘repatriation’ of those records, in cooperation with foreign institutions that provide digitisation and availability through the internet, has been the first stage of our project. However, it is still incomplete because many pieces remain in the collections of foreign researchers, which are more diffi cult to access.

The documents to which we give priority are taken from a wide range that obviously includes written sources but is not limited to the written record in the narrower sense. We are interested in printed material such as newspaper articles, minutes of meetings, unpublished original texts, private documents, letters, poetry, traditional recipes (culinary and medicinal), photographs, iconography, sound recordings and music scores, testimonials (prerecorded or produced ad hoc by our own team), prayers, tunes, reproductions of cultural objects or artefacts, and film footage and recordings of cultural or political events (3). Above all we consider:

- Documents, whether already in archives or private collections. That is, as much the files about the Afro-Brazilian population as, to a lesser extent, the records produced by Afro-Brazilian anthropologists, intellectuals, artists, activists and religious leaders. We can hold temporary exhibits alongside pieces from different archives or museums—pieces that could then be exchanged through a digital lending

- Documents secured or produced by researchers, which we then circulate online, authorising either their partial or full publication during or after the completion of

- Documents created from scratch. These may be testimonies, photographs, music recordings or recordings of how people receive, comment and sometimes dramatize images and documents about their own reality that we present for

For the recovery of the Afro-Brazilian memory, well-known figures in the social, political and intellectual life of Brazil interest us as much as do the anonymous and unknown ones (for example, mães/pais-de-santo, or the first classes of students admitted to a public university as a result of the new quota system). Our project provides constant research and the updating of software or more adaptable platforms (such as a smartphone application that we are developing) to facilitate content management and the creation of digital repositories.

In the first instance, we consider documents and materials produced by people who identify as Black or Afro-Brazilian, because that is where the main need resides. Alongside them, we seek material on Afro-Brazilian religious leaders, black activists, trade unionists, classical and popular musicians, capoeira schools and teachers, maroon community leaders, non-government organisations (NGOs) concerning the Afro-Brazilian population, the Catholic Church (especially the pastoral care of Blacks) and some Pentecostal churches, and the personal archives of components of the Black elite. Also important are unpublished records, or endangered records (often in a state of decay), records produced about or for Blacks or Afro-Brazilians, records of race relations or racist episodes, and more general material about a variety of professional and academic figures. Further, works from travelers, missionaries, diplomats, faith workers, essayists, journalists, anthropologists and other social scientists are of interest.

Collaboration can take various forms. Digital material can be donated, suggestions and criticisms can be made, or someone can construct and curate a virtual gallery consisting of a set of documents focusing on a specific topic made available to the museum from various sources. Our policy is to ask individual researchers to be responsible for the construction of “their” gallery.

Our first phase of activity has brought with it a series of enormous challenges. We had to make quick decisions about managing authenticity (what is an authentic document?), originality (which documents to choose within frequently quite large groups?), property (which property to recognise or reject? And to what extent?), exclusivity, copyright, image rights and privacy (can everything be made public? What is public or private; why, for what purpose; and whom to ask for authorization?), the status of the researcher (what to do with self-taught researchers?), whether and how to incorporate the archives of social movements, associations and NGOs; the type of exchange to interweave with other virtual or digital museums, the relationship to maintain with other digitization projects. We already have received copies of documents, either repatriated or donated, with the support of the Smithsonian Institute, the Archive of Traditional Music at the University of Indiana at Bloomington, the Moorland-Spingarn Research Center at Howard University, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture at the New York Public Library, the Melville J. Herskovits Library of African Studies at Northwestern University, the UNESCO Archives in Paris and the AEL at UNICAMP, Campinas, Brazil.

Such digital generosity and crowdsourcing or collective curatorship is key to the success of the project in a world in which individualism and even selfishnesshas influenced the character of the curator and the scholar. The protection and preservation of the cultural and political heritage of the Afro-Brazilian majority also depends on [ this] digital generosity.In Brazil, where the racial majority has traditionally been dealt with as a minority in the mass media, archives and museums, the Afrodigital Museum and its experiments in the interface of digitazion, visual culture and social media aims at a new positive visibility of the Afro-Brazilian community.

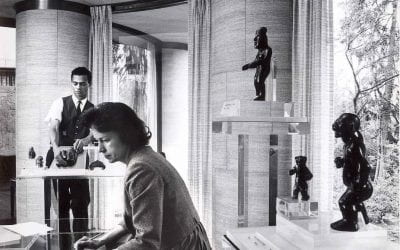

The wall of the Centro de Estudos Afro-Orientais of the Federal University of Bahia (Salvador, Brazil) that hosts the Afrodigital Museum.

Livio Sansone, professor of anthropology at the Federal University of Bahia (UFBA), is the director of the Factory of Ideas Program—an advanced international course in ethnic and African studies—and coordinates the Digital Museum of African and Afro-Brazilian Heritage. Born in Italy, he got his Ph.D. from the University of Amsterdam (1992) and has been living in Brazil since 1992.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.