Renovation in Continuous Movement

Santa Clara and Colonial Museums in Bogotá

With my eyes reflecting my deep sense of amazement, I wandered the streets of Rome—this open-air museum that I was rediscovering step-by-step—with my husband Gustavo Echeverri A., back in 1998 while he was still here with us on earth. I can still smell the hot breeze that circulated in the orange-tinted atmosphere, as we descended the Spanish Steps to the Fontana della Barcaccia.

At twilight, the Spanish Steps we’d left behind us lit up, and we heard the music accompanying the light-as-a-feather models as they walked down the runway of the fashion show Donna sotto le stelle (Women Under the Stars), marking the conclusion of Fashion Week. This experience, in which I took in all at once the ruins of Ancient Rome, the baroque fountain of Pietro Bernini and contemporary Italian fashion, planted a seed that later germinated when I became director of the Santa Clara Museum in Bogotá in 2001.

My Master’s in History and that experience in Rome compelled me to integrate colonial historiography and contemporary art in the Santa Clara Museum. This desire coincided with the urgent necessity of museological renovation. Colombia had approved a constitutional reform ten years earlier, declaring the country a pluriethnic and multicultural state. Museums had not yet caught up.

As I write these lines, I realize I’m weaving these past events with a present in which the protagonists, places and style of this story are very present: Pope Urban VIII, who commissioned the construction of the Fontana della Barcaccia to Pietro Bernini, who finished the fountain with his son Gian Lorenzo Bernini between 1627 and 1628, is the same pope who signed the 1628 decree in Rome for the foundation of the Real Convento de Santa Clara in Santafé de Bogotá—now the Santa Clara Museum.

Finally, the name of the event that closed Fashion Week in Rome coincides with the decoration of the church’s vaulted central nave. Because of these coincidences, I end this introduction with the image of the nave of the former Clarian church, where the nuns devoted to St. Clare prayed for almost three centuries. This mystic sky filled with flowers and stars that today still floats like an inverted vessel has witnessed for more than 20 years around 30 artistic projects. They have opened up historical and patrimonial narratives to diverse languages that represent plural experiences in a country whose natural and cultural resources contrast with the reality of its social inequity and the horror of a war that has caused so much pain in Colombia.

Two Updates and Two Renovations in Continual Change: Dialogues with Contemporary Art and Integral Renovation

These projects are organically connected with the missions of the Colonial and Santa Clara Museums— to “generate a space for dialogue between the colonial patrimony and its relation with the present through conservation, research and outreach,” and have enriched the historical investigation of the cultural processes experienced between the 17th and 18th centuries, deepened by the knowledge gained through the process of cataloguing and publication of our collections.

Recently, through conversations with academics, artists, craftspeople and members of the Afro and Indigenous communities, we’ve hosted special exhibitions representing the territories deep within Colombia and their ancestral knowledge. Likewise, together with the represented communities, we’ve revised the wording used in museum labels in our permanent collections, so that the new museography incorporates the context of the cultural references into its narratives, making visible their contributions to our common memory.

“San Pachito”, cultural showcase within the exhibition “The Chocó region, rivers of gold and of knowledge”, Manuel Amaya Quintero, 2018.

These communities, observed as objects of study through an Europeanizing academic, political and socio-cultural framework that integrated them into a field of knowledge as representatives of exotic lifestyles and cultural production, were utilized to be published and exhibited in scholarly books and 19th-century museums. The weight of this Eurocentric vision is still found within the museum labels of our permanent exhibitions, now being revised with the communities.

To know how to listen to different opinions and dissident voices, to integrate traditional knowledge with new technologies, through plural languages, has been an important part of this labor. I can testify that the essence of my work in the museums has been to become conscious of the importance of the present, which hovers between two centuries, and which opens like a hinge between two eras. Because of this, today we build bridges and point out interpretive paths of critical rupture with a colonial past that inhabits the collective conscience and the forms of social and political relationships, for example, like those exhibited in Hall Five of the Colonial Museum: “The Colony: A Still Present Past.”

Room Five/Sala 5 “La Colonia un pasado aún presente” Óscar Monsalve 2018

Contemporary Art in Santa Clara, Historical Research and Recognition of Intangible Cutural Heritage

The program of special exhibitions hosted by the museum to open dialogues on diverse topics has featured historical themes such as the Colombian foundational myth and that of the bicentennials, the portraits of crowned nuns, politics from the pulpit and the baroque fiesta. Likewise, we have exhibited works of photography and contemporary art that showcase evergreen themes such as death, pain, relations of the feminine to patriarchy and abuse.

And other pressing problems and issues like the climate crisis, survival of Indigenous peoples and their knowledge, displacement and disappearances, the abuse of power in social protests, fashion as social critique and Colombia’s natural and cultural riches, as well as the relationships between colonial iconography, pre-Hispanic rituals and the images of popular Latin American saints.

- Ficha anunciando retiro de pieza por orden del Tribunal Administrativo de Cundinamarca – Exposición “Mujeres ocultas” de María Eugenia Trujillo Manuel Amaya Quintero 2014

- Protest in front of the Santa Clara Museum against the closure of the exhibition Mujeres Ocultas/“Hidden Women” by María Eugenia Trujillo.

All these interventions have had a common visual challenge, understanding how to relate them to the predominantly baroque ecclesastical discourse of the former church

Llanto Celeste/“Heavenly Cry” by Pedro Ruiz

without using these elements as mere backdrop for the artwork. A dialogue emerges from their individual perspectives with the history, practices, representations, atmosphere, trades, iconography and what this former church awakens in each artist.

Exhibit “Quién engendra las gotas de rocío” (“Who creates the dewdrops”), by María Teresa Hincapié

Some exhibitions have been quite challenging, like the exhibition Quién engendra las gotas del rocío “Who Creates the Dewdrops” by María Teresa Hincapié, which represented a challenge in terms of conservation, because a large fallen tree that the artist encountered had to be brought into the Museum after an intense disinfecting process. Cases like this have to be taken into account as we develop policies and procedures for our collections.

Another unusual case was that of Mujeres Ocultas /”Hidden Women” that sparked a chain reaction, expressed through a tutela-thon, 500 small lawsuits known as tutelas brought by a group of Catholic citizens who petitioned the Colombian state that their rights had been violated. In this project, the artist María Eugenia Trujillo created some pieces that simulated the vessel known as a monstrance that holds the consecrated Holy Eucharistic host to emphasize the sacredness of the female body used as a territory of war and machista violence in Colombia.

- Ficha anunciando retiro de pieza por orden del Tribunal Administrativo de Cundinamarca – Exposición “Mujeres ocultas” de María Eugenia Trujillo Manuel Amaya Quintero 2014

- Protest in front of the Santa Clara Museum against the closure of the exhibition Mujeres Ocultas/“Hidden Women” by María Eugenia Trujillo.

Although we had to suspend the inauguration of the exhibition because of an order by the Administrative Tribunal of Cundinamarca, which has jurisdiction over Bogotá, after several sessions of verification and presentation of arguments, the court ruled in favor of the Museum. In the end, the State Council ruled in favor of the artist, confirming that the exhibition did not interfere in worship or with the Catholic religion and that it did not restrict or impede the practice of Catholic beliefs. The court also ruled that closing the exhibit would violate its right to freedom of expression (Spanish-speakers can read more of the ruling “Fallo del Consejo de Estado, Marco Antonio Velilla Niega Tutela 06 -10 – 2014, p. 17).”

The Colonial Museum: A 21st-Century Museum in a 17th-Century Cloister

Between 2002 and 2007, as director of the Colonial Art Museum, together with a new staff, I began implementing some changes through special exhibitions and specific modifications in some of the galleries. The aim was to bring the narratives of colonial memory up to date, according to recent colonial theory and historiography to include those who had been forgotten by history and to bring that knowledge to a wider public.

As we carried out this Project, I began to see the need to start a structural renovation of the entire museum, and, thus, with the support of the National Museum Network, a DOFA diagnostic was carried out to define the roadmap for a new Colonial Museum. This diagnostic tool allowedus to plan the three stages of this transition, each one tied to the each of the three buildings that make up the Colonial Museum: la Capilla de Indios (the Chapel of the Indians), el Claustro de las Aulas (the Cloister of the Classrooms) and the Casa de los párrocos (the Priests’ House).

In the first stage, during 2008, preliminary studies were carried out for the structural renovation of the old Chapel of the Indians and, in 2009, for the 2010 bicentennial celebration, the building was restored, inaugurating its completion with the exhibition Identidades en juego antes de la Independencia (“Identities at Play Before Independence.”)

The second stage began in 2012, with the definition of the terms and budget for renovating the Claustro de las Aulas, and made progress in 2013 with the establishment of a curatorial committee from our advisory council, polling the public as to their conceptions about the colonial period. Based on their concepts, we constructed the first structure from a script that we presented to the public and with which we gathered opinions about the new museography. Towards the end of 2013, we took down and packed up the entire collection under strict conservation guidelines in the newly restored building, a decision that enabled us to develop new curatorial scripts and in the process to verify cataloguing for future publications.

In 2014, the Culture Ministry’s Patrimony Division brought up to date the technical studies for the restoration of the Claustro de las Aulas and while the Urban Conservatorship was approving the plans, we went ahead with the work on the script, consulting with the curatorial committee, the advisory council and Colombian and international experts, inviting them to the VIII Jornadas Internacionales de arte, historia y cultura colonial (the VIII International Workshop on Colonial Art, Culture and History). By the end of the year, we had the first draft of the museum script.

Between 2015 and 2016, while the Claustro de las Aulas was being restored, each member of the curatorial commitee began to work on their museum room with a museographic designer and presented a general plan to the Culture Ministry authorities, headed up by Minister Mariana Garcés; the suggestions were received and meetings held to agree on the next steps.

Restoration of the Claustro de las Aulas in the Colonial Museum.

Likewise, the methodology of sharing scripts was shared with the team of Mexican colleague and the concept of transformation became the linchpin of the process. Each member of the curatorial committee met with their academic counterparts, specialized in the themes developed in each museum hall.

The restored cloister

In 2016, The restored cloister opened to the public to showcase the architectural restoration of this national monument, at the same time that museographic furnishings were being produced. In 2017, the new museography was fully implemented in the five halls.

Montage of the arch with a canopy in the new museography.

The five museum rooms, beginning with Imagen Colonial (“Colonial Image”), and continuing with El viaje, Las Ciudades, Colegiales y Artesanos y La Colonia: un pasado aún presente, form part of a new narrative that we continue to revise according to expectations, reclamations and opinions of the ethnic communities who currently, from diverse perspectives, demand the public representation of their ancestral memories.

- Hall 1 Imagen Colonial (“Colonial Image”)

- Hall 2. El Viaje (“The Trip”)

- Hall 3. Las ciudades (“The Cities”)

- Hall 4. Colegiales y artesanos (“Schoolgirls and Handicraft Workers”)

- Hall 5. La Colonia. Un pasado aún presente (“The Past Still Present”)

Transformation in a Continuing Process

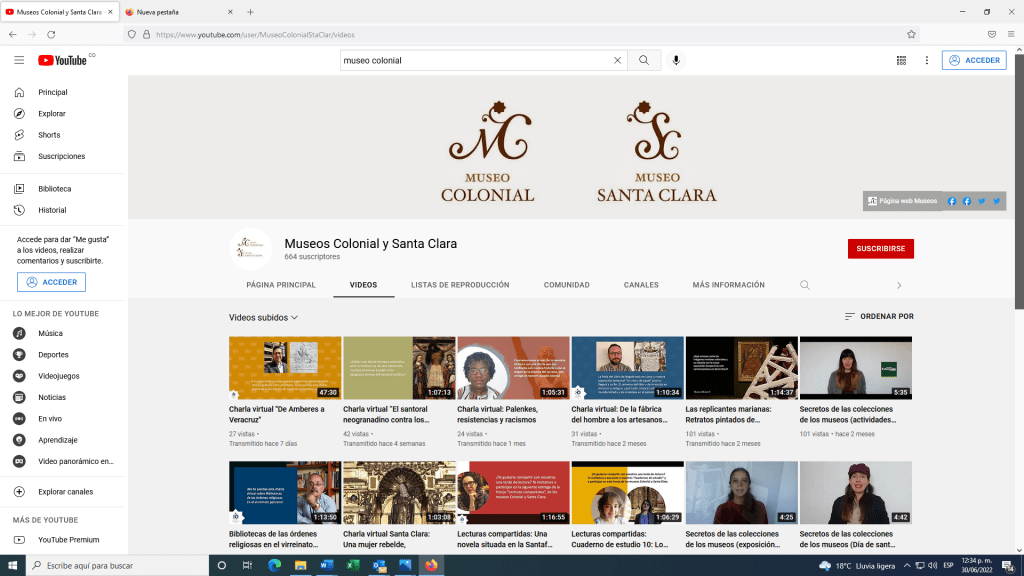

Right now, because of the pandemic in 2020 and 2021, two very different necessities—but somehow complementary— arose that made us connect the museums with a wider public. First of all, the obligation to leave our physical space showed us that beyond a building and its collections, we are communities with living memories, that we can articulate through varied online programming, reaching a broader audience throughout Bogotá, Colombia and the world. In addition, the social protests in the midst of the pandemic made us understand the urgency of opening the museums more and more to include the voices of our cultural diversity.

Digital Programming Colonial and Santa Clara Museums. Perfil YouTube

Thus, the transformation, the narrative axis articulated by all the museum rooms, continues in movement. The work with the communities is necessary because, through their critical view, one can change the terms used in order to adequately describe Afro-descendants and Indigenous people, and to include their voices and terms that were previously excluded in the process of museological scripts.

In this sense, the most important lesson for the interdisciplinary staff of our museums has been to learn to listen patiently, to receive critiques and opinions from the different groups with which we have interacted, and to continue to incorporate the ideas of each group.

This attitude has guaranteed faithfulness to the nature of state museums, now more than ever, when they must respond to an equitable representation of the diverse memories that constructed us as a nation. A nation that is already tired of war has the hope of “a shared vision of the future,” as Jesuit Father Francisco de Roux declared in his recent presentation of the Truth Commission report.

La renovación en los museos Santa Clara y Colonial

Transformación en continuo movimiento

Por María Constanza Toquica C.

Con los ojos de un espíritu sorprendido recorría las calles de Roma en 1998, al lado de mi esposo Gustavo Echeverri A., mientras agradecía a la vida, ese museo a cielo abierto que redescubría paso a paso. Aún tengo fresco en mi memoria el aroma del aire cálido que circulaba en la atmósfera anaranjada, cuando terminábamos de bajar la escalera de la Piazza di Spagna y llegábamos a la Fontana della Barcaccia.

Al atardecer se iluminaron las escalinatas que dejamos atrás, y comenzó a sonar la música que acompañaba un desfile de modelos ingrávidas, con el que se cerraba la Semana de la Moda. Esta experiencia en la que percibí simultáneamente las ruinas de la antigua Roma, el barroco de Pietro Bernini y la moda italiana contemporánea, sembró en mí la semilla, que germinó cuando entré al Museo Santa Clara en 2001 como directora.

Gracias a las experiencias valiosas que precedieron mi quehacer museológico, cómo los estudios de la maestría en historia y el sentimiento que despertó en mí, la percepción estética del desfile de Donna sotto le stelle (Mujer bajo las estrellas), sentí la necesidad de integrar la historiografía colonial y el arte contemporáneo al Museo Santa Clara. Estas experiencias coincidieron con la urgente necesidad de una renovación museológica, acorde con la Colombia pluriétnica y multicultural, que ya había sido reconocida desde hacía 10 años en la reforma constitucional de 1991.

Al escribir estas líneas puedo observar cómo se van entretejiendo estos eventos del pasado, en un presente en el que se articulan los protagonistas, lugares y estilos de este relato: el papa Urbano VIII, quien encarga la construcción de la Fontana della Barcaccia a Pietro Bernini, que la termina de construir con su hijo Gian Lorenzo Bernini entre 1627 y 1628, es el mismo papa que firma la Bula en 1628, en Roma, para la fundación del Real Convento de Santa Clara de Santafé de Bogotá.

Finalmente coinciden el nombre del evento que cerraba la semana de la moda, y la decoración del embovedado de la nave central de la iglesia, hoy convertida en Museo. Por ello, cierro esta introducción con la imagen del embovedado de la nave central de la ex iglesia Clariana, bajo el cual oraron las clarisas durante casi tres siglos. Este cielo místico poblado de flores y estrellas, que aún hoy navega como una embarcación invertida sobre el cielo, ha presenciado desde hace más de 20 años, cerca de 30 proyectos artísticos, que han abierto las narrativas históricas y patrimoniales, a diversos lenguajes para representar las experiencias plurales, de un país cuya riqueza natural y cultural contrasta con la inequitativa realidad social, y el horror de una guerra que nos ha causado tanto dolor en Colombia.

Embovedado Museo Santa Clara Camilo Ponce de León 2013

Dos actualizaciones y dos renovaciones en continuo cambio: diálogos con el arte contemporáneo y renovación integral

Estos proyectos que se vinculan orgánicamente con la misión de los museos Colonial y Santa Clara, que es: “generar espacios de diálogo entorno al patrimonio colonial y su relación con el presente, a través de su protección, investigación y divulgación”, han cobrado realce con la investigación histórica de los procesos culturales vividos entre los siglos XVII y XVIII, y se han enriquecido con el conocimiento generado en el proceso de catalogación y publicación de nuestras colecciones.

Recientemente, mediante diálogos con académicos, artistas, artesanos, y miembros de comunidades afro e indígenas, se han realizado exposiciones temporales que representan los territorios de la Colombia profunda y sus saberes ancestrales. Igualmente se ha adelantado la revisión del lenguaje usado en los guiones de las salas permanentes de los museos, con las comunidades representadas, para que la nueva museografía, incorpore en su narrativa, el contexto de sus referentes culturales, y así visibilizar sus contribuciones a nuestra memoria común.

“San Pachito”, muestra cultural en el contexto de la exposición temporal “Choco: ríos de oro y de saberes” Manuel Amaya Quintero 2018

Estas comunidades, observadas como objetos de estudio por un paradigma académico, político y sociocultural europeizante, que las integró dentro de su campo de conocimiento como representantes de formas de vida y productoras de objetos culturales exóticos, fueron utilizadas para ser publicadas y exhibidas en los libros académicos y en los museos decimonónicos. La carga de este eurocentrismo cognitivo aún gravita dentro los textos curatoriales de las salas permanentes que hoy debemos seguir revisando con estas colectividades.

Saber escuchar las diferentes opiniones y los disensos, para integrar los saberes tradicionales con nuevas tecnologías, mediante lenguajes plurales, ha sido parte importante de esta labor. Podría afirmar que lo central de mi trabajo en los museos ha sido el tener conciencia de la importancia de un presente, que transita entre dos siglos, y que se abre como una bisagra entre dos épocas. Por eso, hoy tendemos puentes y señalamos caminos interpretativos de ruptura crítica, con un pasado colonial que habita el inconsciente colectivo, las prácticas culturales y las formas de relacionamiento social y político, cómo se expone en la sala cinco del Museo Colonial: “La Colonia: un pasado aún presente”.

Room Five/Sala 5 “La Colonia un pasado aún presente” Óscar Monsalve 2018

Arte contemporáneo en Santa Clara, investigación histórica y reconocimiento del patrimonio inmaterial

Dentro del programa de exposiciones temporales que abre el museo al diálogo con diversos tópicos, se han hechos propuestas relacionadas con temas históricos vinculados con el mito fundacional colombiano y los bicentenarios, los retratos de las monjas coronadas, la política desde el púlpito y la fiesta barroca. Así mismo, hemos expuesto obras fotográficas y de arte contemporáneo que tratan temas siempre vigentes como la muerte, el dolor, las relaciones entre lo femenino y el patriarcalismo y el maltrato femenino.

- Exposición “Confrontaciones 2010: Pasados y presentes del mito fundacional colombiano” curaduría de Carlos Rincón Archivo fotográfico Museo Santa Clara 2010

- Exposición “Cuerpos opacos: Delicias invisibles del erotismo místico” curaduría María Constanza Toquica Manuel Amaya Quintero 2013

- Exposición “La ciudad en fiesta: celebraciones de la monarquía en el Nuevo Reino de Granada” curaduría Verónica Salazar y Joan Lluis Palos Manuel Amaya Quintero 2018

- Exposición “El púlpito como campo de batalla”, curaduría Viviana Arce Escobar, Manuel Amaya Quintero 2019

Y, con otros problemas tan actuales como la crisis climática, la sobrevivencia de los pueblos y los saberes ancestrales, el desplazamiento, la desaparición, el abuso del poder en las protestas sociales, la moda como crítica, las riquezas naturales y culturales de Colombia,

- Exhibition: Tigersprung by Barbarita Cardozo

- Exhibition: Hijas del agua/“Threads of Water” by Ana González and Ruvén Afanador

Todas estas intervenciones han tenido un desafío común que ha significado en términos visuales, el saber relacionarlas con el discurso eclesiástico y mayoritariamente barroco de la ex iglesia, sin usarlo solo como fondo visual de las obras. Cada quien dialoga desde su perspectiva individual, con la historia, las prácticas, las representaciones, la atmósfera, los oficios, la iconografía y con lo que esta ex iglesia despierta en cada artista.

Llanto Celeste/“Heavenly Cry” by Pedro Ruiz

Exposición Quién engendra las gotas de rocío de María Teresa Hincapié

Algunas exposiciones han tenido complejidades, como la exposición Quién engendra las gotas del rocío de María Teresa Hincapié, que representó un desafío en términos de conservación, al tener que introducir un gran árbol caído con el que se topó la artista al Museo, tras un intenso proceso de desinfección. Casos como éste, se han tenido en cuenta en la redacción de las políticas de colecciones.

Otro caso inusual, fue el de la exposición Mujeres Ocultas que causó una reacción en cadena, expresada mediante una “tutelatón” (se recibieron cerca de 500 tutelas) gestionada por un grupo de católicos que consideró vulnerados sus derechos. En este proyecto, la artista María Eugenia Trujillo, creó unas piezas que simulaban custodias para resaltar la sacralidad del cuerpo femenino usado como territorio de guerra y de la violencia machista en Colombia.

- Ficha anunciando retiro de pieza por orden del Tribunal Administrativo de Cundinamarca – Exposición “Mujeres ocultas” de María Eugenia Trujillo Manuel Amaya Quintero 2014

- Protest in front of the Santa Clara Museum against the closure of the exhibition Mujeres Ocultas/“Hidden Women” by María Eugenia Trujillo.

Aunque tuvimos que suspender su inauguración por orden del Tribunal Administrativo de Cundinamarca, tras varias sesiones de verificación y contrastación de pruebas, este falló a favor del Museo. Al final, el Consejo de Estado dictaminó a favor de la artista, confirmando que la exposición no interfería en el culto o religión católica, ni impedía o limitaba la práctica de sus creencias y que en cambio el cierre de su exposición sí vulneraba el derecho de libertad de expresión de ella, como se lee en el “Fallo del Consejo de Estado, Marco Antonio Velilla Niega Tutela (06 -10 – 2014, p. 17)”.

El Museo Colonial: un museo del siglo XXI en un claustro del siglo XVII

Entre el 2002 y el 2007, como directora del Museo de Arte Colonial, junto al nuevo equipo de trabajo, inicié algunos cambios mediante exposiciones temporales y modificaciones puntuales en algunas salas. El objetivo era actualizar las narrativas de la memoria colonial según la teoría e historiografía colonial reciente, para incluir a lxs olvidadxs de la historia y a su vez llevar este conocimiento a más amplios públicos.

En el desarrollo de este ejercicio empecé a ver la necesidad de emprender una renovación estructural en todo el Museo, para lo cual, con el apoyo de la Red Nacional de Museos, se realizó el diagnóstico DOFA, como punto de partida, que definió la carta de navegación hacia el nuevo Museo Colonial. Dicho diagnóstico permitió planear las tres etapas de esa transición, cada una vinculada a las tres edificaciones que conforman la sede del Museo Colonial: la Capilla de Indios, el Claustro de las Aulas y la Casa de los párrocos.

En una primera etapa, durante el 2008 se encargaron los estudios previos para la renovación estructural de la antigua Capilla de Indios, y en 2009, para la celebración del Bicentenario 2010, se restauró el edificio y se inauguró la exposición Identidades en juego antes de la Independencia.

Una segunda etapa inició en el 2012, con la definición de los términos y el presupuesto para la intervención del Claustro de las Aulas, y avanzó en el 2013 con la conformación del comité curatorial, de la mesa de asesores y con la consulta realizada a nuestros públicos respecto a lo que pensaban período colonial. A partir de sus imaginarios, construimos una primera estructura del guion que se presentó públicamente y en la que se recogieron opiniones sobre la nueva museografía. Al final de este año se desmontó y embaló toda la colección para resguardarla en el edificio recién restaurado con las debidas condiciones de conservación, decisión que nos permitió adelantar el trabajo con la colección para los nuevos guiones curatoriales y su vez verificar la catalogación de cara a futuras publicaciones.

En el 2014, la Dirección de Patrimonio del Ministerio de Cultura, actualizó los estudios técnicos para la restauración del Claustro de las Aulas y mientras la Curaduría Urbana los aprobaba, avanzamos en el guion, con el comité curatorial, la mesa de asesores y los expertos nacionales e internacionales que invitamos a las VIII Jornadas Internacionales de arte, historia y cultura colonial. Al final de este año ya contábamos con el primer borrador de la nueva estructura del guion.

Entre el 2015 y 2016 mientras se llevaba a cabo la restauración del Claustro de las Aulas, cada miembro del comité curatorial empezó a trabajar su sala con el diseñador museográfico, y se presentó el guion general a la mesa directiva del Ministerio de Cultura encabezada por la ministra Mariana Garcés; se recibieron sus sugerencias y se realizaron reuniones para consensuar los avances.

Restauración del Claustro de las Aulas, sede del Museo Colonial Archivo fotográfico Museo Colonial 2015

Así mismo, se incorporó a la metodología de construcción de guiones que compartió con el equipo la colega mexicana Alejandra Mosco, y se definió como eje del guion, el concepto de transformación. Cada miembro del comité curatorial se reunió con pares académicos, especializados en las temáticas que desarrollaría cada sala y con el museógrafo.

Una vez recibido en 2016 el Claustro restaurado, se abrió al público para mostrar la restauración arquitectónica de este monumento nacional, mientras se comenzaba la producción del mobiliario museográfico. En el 2017, se terminó y montó la nueva museografía de las cinco salas.

Claustro de las Aulas una vez restaurado Manuel Amaya Quintero 2016

Las cinco salas que empiezan con la de Imagen Colonial, y siguen con El viaje, Las Ciudades, Colegiales y Artesanos y La Colonia: un pasado aún presente, forman parte de una nueva narrativa que continuamos revisando de acuerdo con las expectativas, reclamos y opiniones de las comunidades étnicas que actualmente desde diversas perspectivas, interpelan la representación pública de sus memorias ancestrales.

- Hall 1 Imagen Colonial (“Colonial Image”)

- Hall 2. El Viaje (“The Trip”)

- Hall 3. Las ciudades (“The Cities”)

- Hall 4. Colegiales y artesanos (“Schoolgirls and Handicraft Workers”)

- Hall 5. La Colonia. Un pasado aún presente (“The Past Still Present”)

Transformación en proceso continuo

Actualmente, debido a la emergencia sanitaria causada por el Covid-19 durante los años 2020 y 2021 surgieron dos necesidades muy distintas y a la vez complementarias que nos hicieron conectar los museos con más amplios públicos. Por una parte, la necesidad de salir del espacio físico nos demostró que más allá de un edificio y sus colecciones, somos comunidades de memorias vivas, que nos pudimos articular a través de una programación digital variada y llegar a públicos más amplios de la ciudad, del país y del mundo. Por otra parte, en medio de la pandemia, las protestas sociales nos hicieron comprender la urgencia de seguir abriendo los museos cada día más, a las voces de nuestra diversidad cultural.

Así, la transformación, el eje narrativo que articuló todas las salas, sigue en movimiento. El trabajo con las comunidades es necesario para que, a través de la mirada crítica, se puedan cambiar los términos usados para nombrar adecuadamente a los afrodescendientes e indígenas, así como para incluir sus voces y términos que fueron excluidos en los procesos de construcción de los guiones museológicos.

En este sentido, el aprendizaje más valioso por parte del equipo interdisciplinar de los museos ha sido poder desarrollar la escucha paciente, que ha permitido recibir las críticas y opiniones de los diferentes grupos con los que interactuamos, para irlas incorporando a las ideas iniciales de cada uno.

Esta actitud ha garantizado la fidelidad al carácter de los museos estatales, que hoy más que nunca, deben responder a la demanda de una representación equitativa de las memorias diversas que nos construyen como nación. Una nación que ya cansada de la guerra, tiene la esperanza de “una visión compartida de futuro”, como lo dijera el Padre. Francisco de Roux en la reciente entrega del informe de la Comisión de la Verdad.

María Constanza Toquica C. is the director of the Colonial and Santa Clara Museums in Bogotá, Colombia. www.museocolonial.gov.co Instagram/Twitter: @MIStaclara y @museocolonial, Facebook: MuseoArteColonial y MISantaClara; YouTube: Museos Colonial y Santa Clara

María Constanza Toquica C. is the director of the Colonial and Santa Clara Museums in Bogotá, Colombia. www.museocolonial.gov.co Instagram/Twitter: @MIStaclara y @museocolonial, Facebook: MuseoArteColonial y MISantaClara; YouTube: Museos Colonial y Santa Clara

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter – Museums

Editor's LetterMuseums. They are the destination of school field trips, a place to explore your own culture and a great place to run around and explore. They are exciting or boring, a collection of objects or a powerful glimpse into other worlds. Until recently—with...

Art and Public

As Curator of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Harvard Art Museums, I seek to expand the presence of artists from across the world in our collection.

A View of Dumbarton Oaks

Dumbarton Oaks, once the Georgetown home of Robert and Mildred Bliss, is Harvard’s multi-varied Humanities Center in the heart of Washington DC.