The Challenges of Yenny Hurtado

A Woman Who Has Overcome Her Destiny

Yenny Hurtado

Yenny Hurtado is a tall, slim woman whose skin does not reveal her history and much less, her age. She sports a red and pink turban with much grace and simplicity. The naturalness with which she wears it speaks for itself, even before she discusses her African heritage. The turban goes well with her tight blue jeans and her knee-high brown boots. When I first spot Yenny, I’m not sure if she’s the person I’m looking for or someone who lives in the building. “Hi there,” she greets me. “Let’s go to the park next door; I don’t have much time because I have to make my employer’s lunch,” says Yenny.

My first meeting with Yenny was in an apartment complex with huge glass doors. At the entrance was a cement block that resembled marble and a sienna-colored sign reading “Nilo.” Behind the immense glass doors was a three-seat brown sofa, smelling like new leather. A dark-wood table in the center of the lobby was adorned with a vase of white flowers and a hard-cover book with color photographs of Colombia. The apartments have large terraces, almost all of them with a view of Bogotá’s mountains This is where Yenny works.

We walk together to the park on a green-lined street behind the building. In the small park with its tranquil pathway, we observe people running, walking dogs and exercising. In the middle of the street, we find an empty bench to sit and talk. I note how her hands with their white-polished fingernails move fluidly as she converses. Her eyes are large and expressive. I ask her to take off her mask so I can hear her better, and her smile is enviable, displaying perfect white teeth. Yenny’s appearance is far from what one might imagine of a domestic worker. She is beautiful and with a young attitude at her 67 years. She likes dressing well with new clothing. Her vocabulary is quite large her quick understanding of my questions transforms the interviews into an agreeable conversation. Her first job, at the age of eight, was with a wealthy family in Cali. She lived in their house and, in exchange, the family took care of her, paid for her studies and provided material support.

Yenny knows very well what it means to be a maid. In her house, her mother, a domestic worker like Yenny, supported her eight children with the effort and dignity of those who clean the houses of others in order to put bread on their own table, Yenny says. Yenny doesn’t say much about her mother and home, but she tells me she lived with her parents and siblings in a “sort of ugly” house in Puerto Mallarino, a neighborhood in Cali on the edge of the Cauca River. Necessities were never lacking, but her father was quite disorganized and her mother needed a lot of help in taking care of the children—complicated by the fact that Yenny, in her own words, was always a difficult child. So her family decided to give Yenny to work for a family in the Campiña neighborhood, one of the most exclusive areas of Cali.

When Yenny arrived in Campiña, she observed something strange. In her new neighborhood, she was the exception, not the rule. There were no people of color in her new home. The houses were luxurious and large. Families were large and the domestic employees very young. “I was the only Black, “ Yenny says. “In the neighborhood, the other kids would call me “the slave,” “the Black one,” or “that awful Black,” remembers Yenny. But the names did not scare her. Even then, she was fierce and decisive. Her stubborn personality was a weapon she often resorted to. “One kid in the neighborhood wanted to bother me, insult and swear at me. So I took out a knife and threatened to hurt him. Blessed solution! He never bothered me again.”

Around this time, Yenny says, she developed an obsession with clean floors. In her new home, scrubbing the floors with vigor was a sign of virtue and concrete proof that the family had not made a mistake by taking her in. For Yenny, this exercise was therapeutic, a way of channeling what she was living, emotions that she still finds difficult to express, because fortunately, she says, her employers treated her very well. She never experienced painful situation like those she heard about in church, a place where Father Benoît Dumas, a French priest, encouraged her to organize a group of girl domestic workers. So, at age 14, Yenny for the first time brought girls together to achieve her goal: sisterhood.

Her irreverant attitude took her far an wide, to look for herself in other spaces. She sung in the church choir, joined the daughter of María group and finally became a leader of the association of domestic workers in Cali. “Many will say that I did not dound this space, but I did,” says Yenny of this seed that later blossomed into SINTRASEDOM, the National Union of Domestic Workers. When Yenny discovered she was an innate women’s leader, she became unstoppable, tireless, undergoing a metamorphosis and becoming a mother and mentor for all.

A meeting of Sintrasedom in the city of Neiva, in the state of Huila, Colombia.

Yennifer Katherin, a member of SINTRASEDOM Neiva, refers to Yenny as her second mother. Yennifer grew up in the company of Yenny like a vine around a tree. Yenny took care of Yennifer’s son; she dressed him; she fed him. Sometimes she took on the role of grandmother, sometimes that of mother. For Yenny, Yeniffer was one more daughter. “Yenny is a person who gives herself over to others to an extreme. She gives boundlessly and confides in the other person. Sometimes she gets paid well, others times badly. She takes care of everyone, but not eveyone takes care of her,” says Yennifer Catherine, who lived with Yenny for a long time and called Yenny’s son, Sandro, her little brother. Yennifer now lives in Neiva; she’s married and feels sad she won’t be able to take care of Yenny if her health fails, because, as she says, Yenny never abandoned her.

In 1975, Yenny went to Bogotá with the sole purpose of forming a union. She met with several domestic workers and feminist and intellectual women in a conference organized by the Javeriana University. There, several women, among them Yenny, created SINTRASEDOM, one of the largest and oldest unions in Colombia, since it will be 50 years since this determined woman from the Valle de Cauca founded it.

Luz Marina, a domestic worker from Bucaramanga recounts among sobs how the union provided the possibility of traveling to Chile and Argentina. “With Yenny, I have traveled and got to know other counties. I, a domestic worker who barely learned how to work, have stayed at pretty hotels and enjoyed buffet breakfasts,” says Luz Marina. Regarding this, Yenny says that sometimes she was sent airplane tickets to attend meetings of Latin American and international union organizations; she preferred to exchange them for land travel so she could take her colleagues along. “One of my great virtues is that I don’t mix my personal life with my work life,” Jenny tells me. Nevertheless, her son is one of the leaders of the union, and she has frequently taken money from her own pocket to help her fellow workers.

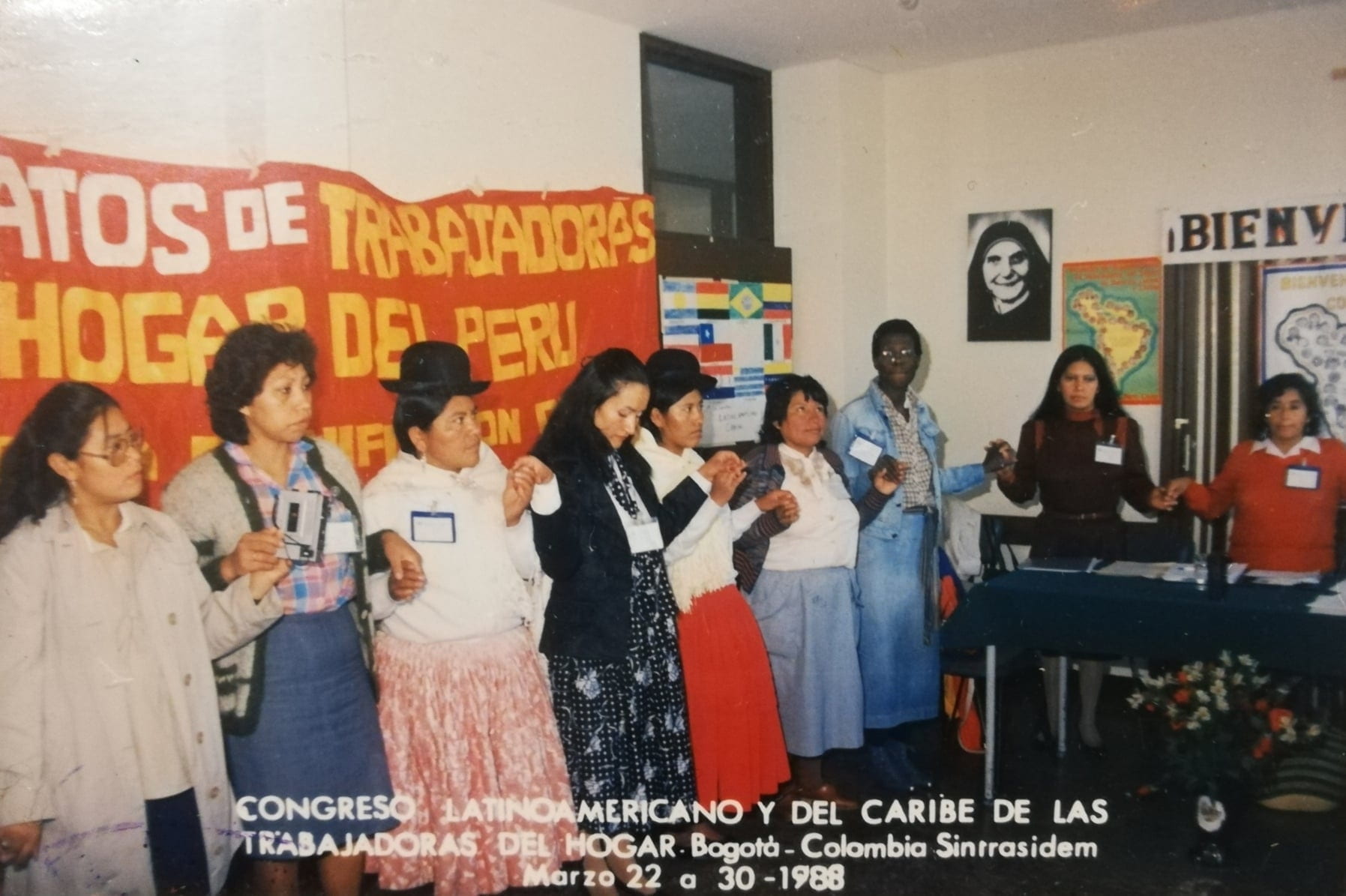

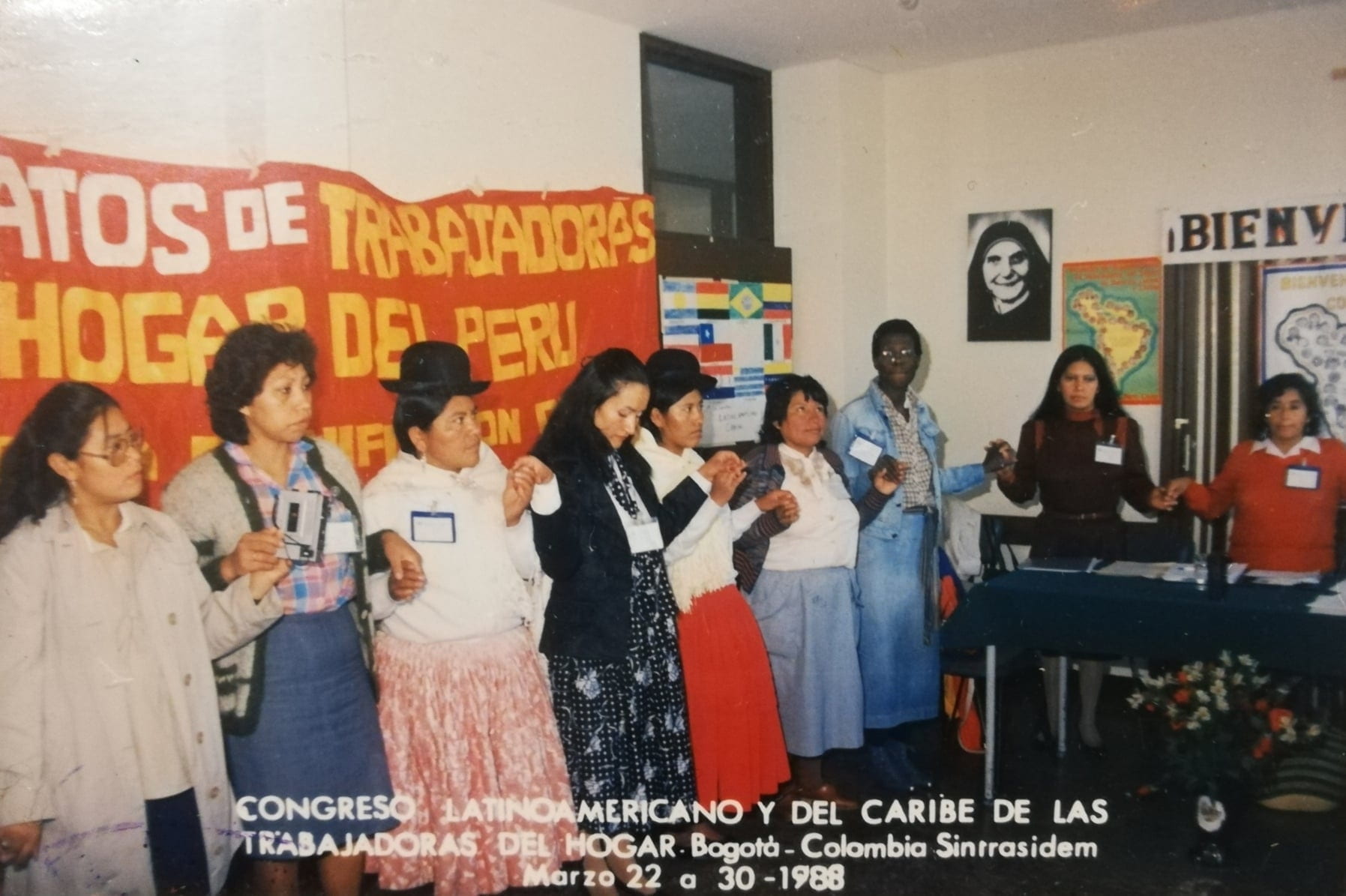

Yenny and her friends from Bolivia in a meeting of the International Federation of Domestic Workers

Her life has been a battle to not allow herself to be defeated by destiny. She felt the weight of racism for the first time as an adult when she joined Coltraba. This happened when Yenny was invited to a feminist conference in Mexico, where the Latin American and Caribbean Confederation of Domestic Workers (CONLACTRAHO, after its Spanish acronym) was founded. Representatives of fourteen Latin American countries attended, and Yenni was the only Afro-descendant representative of a union.

“It’s my problem that I’m the only Black in the majority of places I go,” says Yenny, laughing, despite having felt badly treated by her colleagues.

For Yenny,the message is clear: SINTRASEDOM was founded so that domestic workers could be visible, cultured, educated, brave and proud of their work. Clemencia Romero, Yenny’s former employer, recounts how her family never regarded Yenny as a domestic worker and she never behaved like one. She always gave her opinion and never made one feel as if her work did not have value. “I never saw a person as proud of being a domestic worker as she was,” Clemencia recounts.

It is 11:30 a.m. Yenny checks her watch because time has gone by quickly, and it’s late for lunch. She accompanies me to a nearby bus station and while we are walking along like two friends, she shares with me a declaration I will never forget: “To be a domestic worker has given me everything. To know what I know and the life I have. The day I am no longer a domestic worker, I will not occupy the same place I presently have.”

International meeting in Geneva, Switzerland to recognize domestic service as a an accepted line of work

La lucha de Yenny Hurtado

Una mujer que no se deja vencer por el destino

Por Laura Ramos Rico

Yenny Hutado

Yenny Hurtado es una mujer alta, delgada, su piel no revela su historia y mucho menos su tiempo, trae un turbante rojo con rosado. Lo viste con mucha gracia y sencillez. Casi que su naturalidad para vestirlo me habla por ella, es su cabeza altiva la que me cuenta la herencia africana que habita en la sangre de Yenny. El turbante hace juego con unos jeans azules ajustados, botas café hasta la rodilla. No entiendo si Yenny vive en estos edificios o trabaja ahí. “Hola, mujer”, me dice ella. “Vamos a hablar al parque de al lado, no tengo mucho tiempo porque debo hacer el almuerzo de mi patrón”, concluye Yenny.

Mi primer encuentro con Yenny fue en un conjunto de edificios con puertas grandes de vidrio. En la entrada hay un bloque de cemento blanco muy parecido al mármol y una placa con letras color siena que dice “Nilo.” Detrás de las inmensas puertas, un sofá de tres puestos color café y olor a cuero nuevo. En una mesa de madera oscura, al frente del sofá, habita un jarrón con flores blancas y libros de pasta dura con fotografías a color de Colombia. Los apartamentos tienen terrazas amplias, casi todos con vista a los cerros de Bogotá. Así es el lugar donde Yenny trabaja.

Caminamos juntas al parque, que queda detrás del edificio, es una calle verde con un parque pequeño y un corredor tranquilo. Se ven personas trotar, pasear perros, hacer ejercicio. En la mitad de la calle, hay un banco desocupado y nos sentamos a hablar. Noto el movimiento de sus manos al hablar, sus dedos son delgados y tiene las uñas blancas Sus ojos son grandes y expresivos. Le pido que se quite el tapabocas para oírla mejor y noto que su risa es envidiable, dientes blancos perfectamente ordenados. Yenny dista mucho del imaginario de una trabajadora doméstica. Es hermosa y de actitud joven a sus 67 años. Me cuenta que siempre le ha gustado vestir bien, usar ropa nueva. Tiene un amplio vocabulario y su facilidad para entender mis preguntas hace de la entrevista una conversación agradable. Me cuenta que desde los 8 años trabaja. Su primer trabajo fue los para una familia adinerada en Cali.Yenny vivío en la casa que trabajó y a cambio la familia para que trabajaba, la cuidó , pagó sus estudios y le ofreció condiciones materiales.

Yenny conoce muy bien lo que significa ser una empleada doméstica. En su casa, su madre trabajaba como empleada doméstica y mantenía a sus ochos hijos con esfuerzo y dignidad limpiando la casa de otros para llevar pan a su mesa. De su madre y hogar dice poco, pero me cuenta que vivía con sus papás,y sus hermanos en una casa “ feita”, como dice ella, en Puerto Mallarino, un barrio de Cali a orillas del río Cauca. En casa las necesidades nunca faltaron, su papa era un desorden y su mamá necesitaba mucha ayuda para cuidar a sus hijos, sumado a que, en palabras de Yenny, ella siempre fue una niña terrible. Es así como siendo apenas una niña su mamá decide entregarla a una familia en el barrio la Campiña, uno de los sectores más exclusivos de Cali.

Cuando Yenny llegó a la Campiña, notó algo particular, en este nuevo barrio ella era la excepción y no la regla. En su nuevo hogar no habían personas de color. En la Campiña las casas eran lujosas, grandes. Las familias numerosas y sus empleadas domésticas muy jóvenes. “La única negra, era yo,” cuenta Yenny. “En el barrio los demás niños me ponían apodos: “esclava”, “negra”, “negra horrible.” Pero eso jamás la asustó. La niña de ese entonces era indómita y decidida. Su personalidad flemática fue la espada a la recurrió varias veces para hacerse valer “Una vez un chinito se quería meter conmigo, quería insultarme y decirme groserías. Entonces yo saqué un cuchillo y lo amenace con herirlo ¡Santo remedio! Nadie se volvió a meter conmigo”.

Durante este tiempo, Yenny desarrolló una obsesión por los pisos limpios, en su nueva casa restregar los pisos con ahínco era sinónimo de virtud, la prueba fehaciente que no se habían equivocado de niña, pero para Yenny este ejercicio fue terapéutico, era su manera de canalizar lo que sentía, emociones que todavía le cuesta exprensar. porque afortunadamente, dice ella, sus patrones han sido muy buenos. Nunca vivió situaciones dolorosas como las que conoció en la iglesia, lugar en el que formó su primera asociación de niñas trabajadoras del hogar con el padre Benoît Dumas, un francés que animó a Yenny, por primera vez, a sus catorce años, a reunir mujeres entorno a un propósito: sororidad.

Encuentro de Sintrasedom en la ciudad de Neiva, departamento del Huila, Colombia.

Su actitud irreverente la llevó siempre a otros lugares, a buscarse a sí misma en otros espacios. Fue corista en la iglesia, hija de María y finalmente líder de la asociación de mujeres trabajadoras de hogar en Cali. “Muchos podrán decir que yo no funde ese espacio, pero sí lo hice”, menciona Yenny de esta semilla que más tarde sería el aliento de vida para SINTRASEDOM, el Sindicato Nacional de trabajadoras del Servicio Doméstico.

Cuando Yenny se descubre como líder para las mujeres, se vuelve imparable, incansable, sufre una metamorfosis y finalmente descubre que puede desplegar sus grandes alas y convertirse en lo que muchos afirman de ella, una madre para otros.

Yennifer Catherine, una integrante de SINTRASEDOM Neiva, se refiere a ella como su segunda mamá. Yennifer creció en compañía de Yenny como una enredadera en un árbol. Yenny cuidó al hijo de Yennifer, lo vistió, lo alimentó; hizo las veces de abuela y las veces de mamá. Para Yenny, Yeniffer era una hija más “Yenny es una persona que se entrega demasiado a los demás. Da sin medida y confía abiertamente en el otro. A veces le pagan bien, a veces le pagan mal. Ella cuida de todos, pero no todos cuidamos de ella”, dice Yennifer Catherine, quién vivió con Yenny mucho tiempo y llamaba a Sandro, el hijo de Yenny, hermanito. Ahora Yennifer vive en Neiva, está casada y se siente triste de no cuidar a Yenny cuando su salud flaquea, porque como ella dice, Yenny nunca la abandonó.

En 1975, Yenny viajó a Bogotá con el único propósito de formar un sindicato. Se reunió con varias trabajadores domésticas y mujeres feministas e intelectuales de la época en un congreso organizado por la Universidad Javeriana. Allí, varias mujeres, entre esas Yenny formaron SINTRASEDOM, uno de los sindicatos más grandes de Colombia y también de los más antiguos, porque este año cumple 50 años de ser fundado por manos de esta mujer Valle caucana.

Luz Marina, una trabajadora doméstica de Bucaramanga se cuenta entre sollozos que el sindicato le ha dado la posibilidad de viajar a Chile y Argentina. “Con Yenny he viajado y conocido otros países. Yo, una empleada doméstica que apenas aprendí a leer, me he quedado en hoteles lindos y he tenido desayunos buffet,” relata Luz Marina. Sobre esto, Yenny me cuenta que a veces le envían pasajes de avión para asistir a foros de los sindicatos latinoamericanos o internacionales y ella prefiere cambiarlos por tiquetes terrestres y así llevar a sus compañeras. “Una de mis grandes virtudes es que no mezclo la vida personal con la laboral,” me dice Yenny. Sin embargo su hijo es uno de los líderes del sindicato y de su bolsillo ha salido muchas veces dinero para ayudar a sus compañeras.

Yenny y sus compañeras de Bolivia en un encuentro de la Federación Internacional de trabajadoras del Hogar

Su vida ha sido una batalla por no dejarse vencer por el destino. Sintió por primera vez de adulto el peso del racismo sobre su piel. Esto sucedió, cuando Yenny fue invitada a una conferencia feminista en México, dónde se fundó la CONLACTRAHO, La Confederación Latinoamericana y del Caribe de Trabajadoras del Hogar. En esta mesa que reunió 14 países de Latinoamérica, Yenni era la única mujer afro en representación de un sindicato.

“Es es mi problema, que a la mayoría de lugares a los que voy soy la única negra”,me dice Yenny riéndose, a pesar haberse sentido maltratada por sus compañeras.

Para Yenny el mensaje es claro, SINTRASEDOM se fundó para que las mujeres trabajadoras domésticas fueran visibles, cultas, preparadas, aguerridas y orgullosas de su trabajo. Clemencia Romero, una ex patrona de Yenny cuenta que en su familia jamás la vieron como una empleada doméstica y que ella jamás se comportó como una. Siempre dio su opinión y nunca hizo sentir que su trabajo significaba menos. “Nunca vi una persona tan orgullosa de ser trabajadora doméstica, como ella,” me cuenta Clemencia.

Son las 11:30 de la mañana, Yenny revisa su reloj porque nota que el tiempo ha pasado inadvertido y ahora es tarde para el almuerzo, me acompaña a una estación de bus próxima y mientras caminamos, como dos amigas, me comparte una frase que jamás olvidaré: “Ser una trabajadora del hogar me lo ha dado todo. Conocer lo conozco y la vida que tengo. El día que deje de ser empleada, no voy ocupar el mismo lugar que ocupo ahora.”

Encuentro Internacional en Ginebra Suiza para el reconocimiento del servicio doméstico cómo un trabajo remunerado y decente

Laura Ramos Rico is a literary writer and Master of Journalism at the Universidad de los Andes in Bogotá. She has worked as a professional researcher at the Center for Interdisciplinary Studies (CIDER) at her university and has written for Colombian media such as shock, baudó and cerosetenta.

Laura Ramos Rico es literata y estudiante del magister de periodismo de la Universidad de los Andes. Ha trabajado como profesional de investigación para el Centro de Estudios Interdisciplinarios – CIDER- de los Andes y escrito para medios nacionales como shock, baudó y cerosetenta.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter

Editor's Letter Upstairs, Downstairs (and In-Between)When Argentine biologist Otto Solbrig was interim DRCLAS faculty director many years ago, he commented more than once that ReVista did not feature enough photos of middle-class people. I tried to respond to his...

Paid Domestic Workers, Women and Democracy

I first visited Peru in 1995 as a graduate student and junior member of a Latin American Studies Association delegation to examine the state of democracy in that country on the…

Invisible Commutes

English + Español

Belén García, a Colombian domestic worker, wakes up at five in the morning every day in her home in the chilly mountains of southeastern Bogotá. After taking a shower, she dresses in several…