The Complexities of Art and Life

Knowing Laura Aguilar Through Her Fat Body

The seminar on Queer/Crip Wastelands, a course which examined the intersections of queerness, disability and the environment, was one of the liveliest I’ve ever taken. During our discussion of ecofeminism, my classmate Emma offered us a photograph she thought could help us think about feminist art in which humans embraces the environment. Turning her MacBook towards the class, she revealed a black-and-white photo of nude women laying on top of foliage. In the middle of the photo laid the late Chicana lesbian portrait photographer Laura Aguilar on top of a bed of rocks. The class nodded and murmured in agreement. This photo did symbolize an ecofeminist embrace of the environment; a harmony between humans and the earth. The conversation had moved on, yet my mind lingered on Aguilar’s body.

I identify as queer, Dominican, trans femme and, importantly, as fat. I use the term “fat” primarily to describe the size, shape and density of my body. The term, however, also signals the political nature of my relationship to my body. For decades, “fat” has been reclaimed from the society’s derogatory usages—laziness, unintelligence, morbidity and death. I describe myself as “fat” because I have learned to love my fatness and I view it as beautiful and life-enriching. Those meanings came to odds with this photo of Aguilar.

Picture of the author taken April 29, 2023.

I work to have a loving relationship with my body. In a world in which bodies like mine are deemed undesirable, I affirm my body as much as I can to counteract the ways people (myself included) attempt to devalue it. One strategy I use to love my body is to publicly display it online. My Instagram account has become a space to curate beautiful content in which I show off my fat body in the newest fashions. The entire process is gratifying. From finding cute clothes that fit me, to the duration of time my friends give me to direct me through different poses to the words of affirmation, photographing myself has become a ritual where I deeply love my body and I invite my community to do the same.

Laura Aguilar, Motion #58, 1999. Credit to the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016.

I was struck by Aguilar’s self-fashioning in Motion #58 (1999). She is not looking into the camera. She is not “striking a pose.” The photo is in black and white. Nobody is touching her in any flattering ways. In this photograph, Aguilar lays corpse-like. My first thought looking at Aguilar was “how could someone photograph themselves like this?” The composition of this photo does not cohere to what we would think of as a prideful, beautiful, dignifying portrait. I felt uncomfortable. I would never photography myself like this.

One of the greatest powers of art is its ability to turn our gaze back onto ourselves. Aguilar’s portrait helped me interrogate my investments in representing myself beautifully. This interaction with Aguilar was enough for me to choose her to be the first chapter of my dissertation. Researching Laura Aguilar would be an emotional, introspective process connecting with an artist we lose too soon to the intersecting systems of oppression.

Photography as Survival

Laura Aguilar was born on October 26, 1959, in San Gabriel, California. Both Mexican- and Irish-American, Aguilar, one of three siblings, was the daughter of Paul Aguilar, a second-generation Mexican-American, and Juanita Grisham, whom art historian Sybil Venegas describes as a “fifth-generation documented Mexican Californio native.” Grisham’s patrilineal heritage is connected to Mexico, and her matrilineal heritage has roots in Ireland.

Laura Aguilar’s education was somewhat traumatic because of her auditory dyslexia, a learning disability which made it difficult for Aguilar to process and pronounce written and aural language. In an interview later in life, Aguilar reflected on how she was bullied by teachers and students, recounting how teachers got tired of asking to repeat and clarify herself. They asked Aguilar’s classmates to “translate.” Students were equally cruel. One mockingly said that “it’s cute how Laura can’t talk, right?” Aguilar noted that she graduated from high school without being able to read. Her disability, among other aspects of her life, contributed to depression for most of her childhood.

Photography saved Aguilar’s life. After failed attempts to study photography in higher education, Aguilar picked up photography through aspiration to be like her brother, Lee. Sybil Venegas, one of Aguilar’s former educators, mentors and later close friend, said that “at the opposite end of dyslexia was the camera, the means to reach a place of fluid communication, of grace and childish wonder.” Photography was a positive art form for Aguilar both because it connected her to her brother and because it gave her a way to express herself. In the disabling spaces Aguilar occupied for most of her life, Aguilar felt silenced and excluded from social relations. Photography allowed her to articulate herself and manage her depression. Her photography earned her fame and notoriety through her impactful portraiture of (often nude) queer people of color. Her highly impactful photography emerged during the Chicano Art Movement in Los Angeles during waves of increased photography of Chicanxs and other historically minoritized subjects.

Photography helped Aguilar embrace her sexuality. In a series she made titled Latina Lesbians, Aguilar was commissioned to take potraits of lesbian lawyers, teachers and therapists working with the company Connexus, which helped people who were coming out as LGBTQ+. The photos in these series feature the feature at the top of a white sheet with hand-written words by the photographic subjects. Aguilar reflected that she had “strange sterotypes” of only knowing lesbians as white because of the media. It is in through this series which Aguilar came out as a lesbian. And although she did come out, she added that she “wasn’t that out.” For her, this series “was a way of finding people who were comfortable with themselves,” so that she “could be comfortable” with herself. As we will see, comfort was a complicated position Aguilar strived for as a Chicana, disabled, working-class, fat lesbian artist.

Laura Aguilar, Julia, from the Latina Lesbian series, 1987. Credit to the Smithsonian American Art Museum and the Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016.

Laura Aguilar, Laura, from the Latina Lesbian series, 1986. Credit to the Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016.

A Photographer of Race

Laura Aguilar is most known for her arresting work titled Three Eagles Flying (1990). This black and white triptych (three-part portrait) begins with an American flag hanging down on the left side. In the far right photograph, a Mexican flag hangs down parallel to the American flag. Aguilar stands in the middle of the portraits in bondage. The Mexican flag is wrapped around Aguilar’s head so that its eagle masks perfectly over her face. The American flag is wrapped around the lower half of her body, accentuating her curves and her belly. The flags and her limbs are constricted by a thick rope that runs from her neck, between her exposed breasts, around her wrist, and finally under her stomach.

Laura Aguilar, Three Eagles Flying, 1990. Credit to the J. Paul Getty Museum and the Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016.

Three Eagles Flying is esteemed for its critiques of racialization, ethnicity and the nation-state. In this portrait, Aguilar is constricted between the United States and Mexico. Her bare breasts capture the tension that she is not completely enveloped in either country. Her concealed face adds to domination in the portrait by how she is unable to meet her viewers’ gaze. We are not able to see her face and know how she is doing. This portrait represents the experience of unbelonging that many Chicanx and Latinx people relate to living in the United States.

Aguilar was inspired by her mother’s feelings of unbelonging to create Three Eagles Flying. She noted in an interview that on a family trip to Mexico, she observed how people treated her mother. Her mother did not speak fluent Spanish and neither did she. Her mother’s complexion led her to be treated as a white American rather than a Mexican woman with Irish heritage. Three Eagles Flying, then, is a physical representation of Aguilar’s mother’s strife of neither being American nor Mexican enough.

My own experience resonates with Three Eagles Flying. My parents migrated from the Dominican Republic for the promises of upward mobility the United States offered. Being socialized through the New York City public school system, my mother insisted on our assimilation to make good on the opportunities that came with the American Dream. The ways we prioritized English in our household coupled with my lighter complexion disconnected me from my Dominican heritage. This disconnect was further perpetuated by how people did not immediately recognize me as Dominican. I am still believed to be Puerto Rican or a white American before I am Dominican. When I look at Three Eagles Flying, I imagine my body where Aguilar’s stands with my face concealed by the Dominican coat of arms. However this conversation is not just about nationality and fitting in within a singular sense. In this photo, I am moved by how Aguilar uses her naked, fat body to bear the weight of her heritage.

An Archive of Depression

In my research, I learned that Aguilar’s relationship to her fatness goes unspoken amongst most academics. The more that I researched her, the more I encountered her depression and the myriad of emotions she felt about herself. In one interview I read about in her retrospective catalogue book titled Laura Aguilar: Show & Tell, Aguilar once described herself simply as “fat.” She explained that she did not “like being this way,” and that she “felt a lot of anger” about her size. She saw her work as her way of “coming to terms” with herself. These sentences insinuate more than fleeting emotion. People’s negative relationships with their body often begins from an early age. Fat studies educators and fat activists teach us that we first learn that being fat is bad from our parents, our schools and the media. Aguilar’s brief comments on her body read like a brief cursor over a long struggle with living in a body that was always treated like a problem. Further research confirmed that my intuition was correct.

Laura Aguilar did not simply hate her body. She did all she could to be happy despite it. In the spring of 2023, I found recordings of Laura Aguilar’s video art. She recorded videos of herself in 1995 titled “The Body,” “The Body 2,” “Talking About Depression 1,” “Talking About Depression 2” and “The Knife.” These videos were like diary entries or “vlogs” where she spoke candidly about her body. In these videos, Aguilar talked about the ways she was working on herself. She went to therapy. She dieted. She wished to harm herself but never followed through. She attempted to date but got stood up when the day came. When her strategies failed and she did not achieve the smaller body she wanted, she met her body where it was. Before and after her showers, Aguilar would stand in front of the mirror and stared at her naked body. Her early naked photography was a strategy she used to make herself feel guilty for being fat that only backfired on her and turned into an accidental act of self-love. These videos are rife with contradictory thoughts and actions. And this is what it can feel like to be fat: to live through persistent traumas of being deemed undesirable while longing for the ways to find peace and happiness through it all.

One of the most heartwarming experiences I hold onto about Aguilar is the pleasure she felt. At a visit to a Chicano Studies class at the University of California, Los Angeles in 2006, Aguilar reflected on Motion #59 (1999), a photo in which she is naked and bent over with two other naked women bent over her. She told the students this photo marked a time when she felt “nurtured” and “allowed” herself to be nurtured for the first time in her life.

Laura Aguilar, Motion #59, 1999. Credit to the Pheonix Art Museum and the Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016.

This contact with other women means more considering how Aguilar characterizes her life by naming the lack of touch she felt. In one video and one handwritten note shared by an Instagram account run by her estate, Aguilar wrote “the untouched / landscape of my body / the landscape / the soul is dry / soil is dry / and brokedn inside” This wording metamorphosizes her body as a natural space, an ecosystem. We can read the words “untouched landscape” as an acknowledgment of the lack of physical touch Aguilar received and an implicit longing for just that.

Instagram post by user @laura_aguilar_photo, November 6th, 2022. Credit to the Laura Aguilar Trust of 2016.

This photo indexes a moment of pleasure shared amongst three women. Aguilar’s memory of this photo seven years later is a testament that she was touched in and by this photo. Touched in the sense of the physical contact in the photo and touched by the void which this contact filled. Considering that Aguilar regards her body as an untouched landscape, then this a moment the landscape was finally traversed.

How to Remember Laura Aguilar

Thus I learned I had more in common with the woman lying down than I thought. Laura Aguilar’s photography does not perfectly crystalize into a triumphant fat politic. I cannot look at a single photo of hers to learn her story of her body. Our lives are more complicated than the still moments we create. The best word to describe Laura Aguilar’s relationship to her body is “ambivalent.” The ebb and flow between loving and hating her body is the most realistic relationship someone can have with their fat body. Oppression affects us, but it does not always succeed in depriving us of hope and joy. While Aguilar may not have posed glamorously for her photos, I feel with her through this ebb and flow. My investments in being confident and beautiful are fraught. I always fear for the moments when my self-love falters and runs out. The rhetoric of loving yourself, Caleb Luna explains, “places the burden on us to account for the shortcomings of those around us; to perform the labor of care not just for ourselves but for the care that others are not showing us.” Laura Aguilar shows us how historically minoritized subjects are not automatically given care.

It is my hope that people look at Laura Aguilar and hold all of her identities together. She was a cisgender, Chicana, dyslexic, low-income, fat lesbian who was chronically depressed. Scholars and critics sometimes treat race and ethnicity as the primary markers for how we study people and their work. Laura Aguilar’s life is a testament to the truth that the body, with all of its visible and invisible markers, matters. Learning about her fatness, her disabilities and her mental health invites us to learn about Aguilar on an intimate level. Though I learned about her two years after she left us, I will forever be touched to have learned about her grief, her sadness, her smiles and her strides to be at peace.

Joe Baez is a Ph.D. candidate in American Studies at The George Washington University. In her dissertation, she looks at how fat women and fat trans femmes of color represent themselves in the arts and in media in response to the ways they are expected to be ashamed of their bodies. As a scholar, Joe radically dreams of transforming the ways we love ourselves, our bodies and each other. You can connect with Joe via e-mail at joebaez@gwu.edu and on Instagram and Twitter @thejoebaez.

Related Articles

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

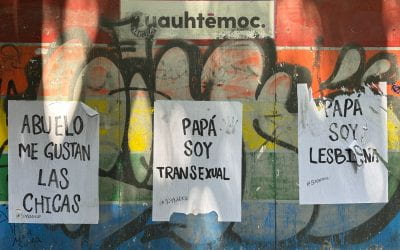

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.