The Law and Life

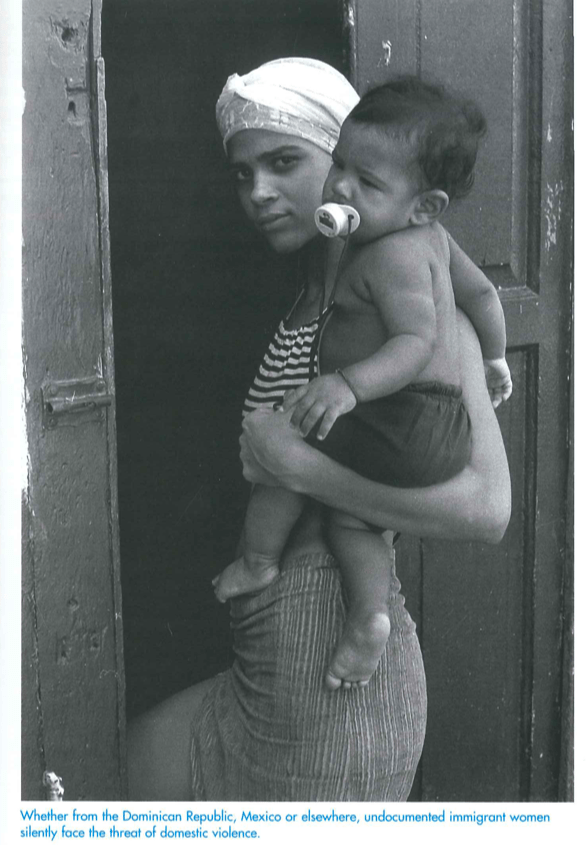

Battered Undocumented Women

Vicky arrived with visible anxiety at the legal assistance office where I was volunteering in our small Northern California town of Napa. Sitting uneasily across the desk from me, she whispered her answers to the long list of questions for new clients seeking relief and recourse for domestic violence. About halfway through the long list of yes or no questions, I asked Vicky (all names have been changed to protect confidentiality) if she had ever called the police for protection from her abusive husband or if she had ever obtained a restraining order against him. Looking at me sadly, she replied simply, “No tengo papeles.” I don’t have papers.

Our office was the first legal or public agency in which she had ever stepped foot in the several years she had lived in the United States. I still recall how terrified she was to be in that office, how she was at once extremely guarded and completely desperate for support.

Vicky, a Mexican immigrant who had come to the United States without family and with few friends, had married a U.S. citizen who turned brutally violent. He had refused to process the paperwork to regularize her immigration status. Vicky was acutely aware of her precarious legal status and of the constant threat of deportation. Her abusive husband often used undocumented status as a technique to control and subdue her. Vicky seemed torn between her profound fear of U.S. legal agencies and her need for institutional support. She shared all the fears, anxieties and needs of the many battered women I had seen walk through the office doors, but hers were compounded and exacerbated by her political and legal vulnerability as an undocumented immigrant.

Vicky is one of the many battered undocumented women for whom conventional legal and institutional processes are unavailable, even alienating and marginalizing. I decided to take a closer look at the women whose daily experiences, relationships, and life biographies are deeply shaped by their political and legal entitlements. For my senior thesis at Harvard, I drew on the voices and narratives of ten battered undocumented Mexican immigrants in Northern California, who were self-petitioning for immigration regularization under the Violence Against Women Act (VAWA) to explain how their daily lives were structured by the laws, institutions and social discourses surrounding immigration and undocumented immigrants.

Each one of these women experienced first-hand the dramatic shifts in California laws and public attitudes towards immigrants over the last decade and a half. These women found themselves facing the context of a national crack down on undocumented immigration, which was reflected in legislation surrounding drivers license eligibility, legal services funding, border control, and, most prominently, Proposition 187. Most of the women interviewed were living undocumented in California during the time period preceding and following 1994 passage of Proposition 187, which explicitly excluded undocumented immigrants from receiving public assistance, health care, even public education and required public officials to check the immigration papers of those seeking services. Although the law was declared unconstitutional by the Supreme Court, Proposition 187 reflected and perpetuated a culture of xenophobia in the state and sent an important warning message to undocumented immigrants.

Women such as those I interviewed have traditionally been viewed unidimensionally by scholarly literature—either as immigrants or as battered women. The sociological literature on immigrant settlement and the battered women’s movement offer important insights into the experiences of battered undocumented women, but offer prescriptive paths which are largely contradictory. Whereas the former focuses on the immigrant community and family as retreats from social abuse, the battered women’s literature views the home and family unit as sources of oppression. Read against each other, it is evident that neither literature fully takes into consideration how law and politics shape undocumented immigrants’ daily lives and experiences.

The extensive literature about battered women talks about empowerment through public participation and social integration. A key to survival in the battered women’s movement is to take refuge in public space. Women are encouraged to get jobs, utilize public benefits, join community groups and generally engage in the public sphere. However, that is precisely what the battered undocumented immigrant cannot do. Public space is to be avoided at all cost.

Leticia’s story illustrates the extent to which she felt excluded from and marginalized in public space as an undocumented immigrant. A formerly undocumented mother of two, Leticia told me, “The only time I left the house was to pick up [my employer’s] daughters. And she always told me not to go out because immigration would pick me up. She always said, “la migra would be here, there…I was scared to leave…I felt the doors were closed to me.”

Leticia’s memories of being undocumented are painful. She recalled, with tears in her eyes, that her life in the eight years before receiving immigration papers was characterized by constant fear. She endured exploitation by her employer because she feared her undocumented immigration status would prevent her from finding another job. When she was physically abused by her husband, she did not call the police out of fear that she would be arrested and deported. Leticia would not even attend a support group until she got her papers because she didn’t feel safe from INS detection there. Even when she wanted to leave the house, transportation was difficult because she was ineligible for a drivers’ license. In every way, Leticia’s immigration status transformed the public sphere into a place of intense risk and marginality.

Leticia is not alone. The battered women I interviewed all spoke of this intense fear, both as a result of domestic violence and the terrifying constrictions of institutional hurdles and “illegality.” The battered women’s movement offers important insights into the gender dynamics of the home and family, but the stories and experiences of these battered undocumented women challenge the movement’s endorsement of the public sphere as a great liberator and a realm of equal entitlement and privilege.

The sociological literature on immigrant settlement, by contrast, specifically recognizes the marginalization of immigrants and the risks associated with participation in the mainstream society. The literature posits the family unit and the ethnic enclave as antidotes to discrimination and intimidation in the broader culture.

Although the sociological literature makes great strides in recognizing the resources of the immigrant family and the unique situation of new immigrants in the larger culture, that literature tends to overlook the reality of conflict in the family, the gendered nature of conflict, and the specific laws and institutions which perpetuate immigrant marginality.

These women’s accounts of the role that their friends and families played in perpetuating, responding to, facilitating escape from and otherwise dealing with the abuse in the women’s relationship afford a particular opportunity to explore a unique—and largely overlooked—range of experiences within the social network.

Catalina, a pretty young woman from Jalisco who works in a San José hair salon, gave me a vibrant example of how her social network was even more remote from the idealized portrait of immigrants’ social networks as coping mechanisms or places of retreat. At one point in the interview, while fumbling to describe the way her six brothers control and isolate her, Catalina pulled down her shirt and pointed to a large bruise: “In fact, there is one thing that happened very recently to me. One of my brothers hit me. I have some bruises. I have even more on my body, but I am ashamed to show you.” Catalina proceeded to explain, in detail, the physical and emotional abuse she suffers from her family, which intentionally isolates her and prevents her from cultivating and pursuing relationships outside the family. Catalina described her family network as extremely controlling, possessive and unsupportive: “Not even then do I have any emotional support at home. [The people in my family] don’t consider my emotional state.” And although her relationships with her friends and extended family have not been as intensely negative, Catalina assured me, with tears in her eyes, that she had many stories of being manipulated, controlled and misled by family and friends.

Catalina’s story offers an important counterpoint to the fundamental argument that social networks offer reprieve for immigrants from the challenges, abuses and insecurities of the outside world. The entire premise of social network theory has been that networks are, by nature, integrative and encouraging of social participation. But Catalina and others have found their social networks not only to be sources of intense abuse and insecurity, but also causes of isolation and alienation.

“Intentional isolation” has been recognized as a tactic of abusive spouses, who seek to control their partners by cutting off their social interactions. The much heralded “wheel of power and control” which depicts cycles of violence and contrition in abusive relationships, for example, features intentional isolation as a stage of abuse. For the women who experienced that direct form of imposed social isolation, the network becomes even more entrapping and oppressive.

The conclusion of my interviews, of course, does not imply that all family interactions for immigrant women are abusive or manipulative. To the contrary, several of the women described their relationships with their siblings to be their greatest source of support and comfort. Female networks did, at times, provide information and support for the women interviewed. A few of the women reported relying deeply on friends from Mexico and new friends they had made in California.

However, in the complex interaction of domestic violence and “illegality,” the advice and attitudes of friends and family cannot be conceived of simply or in static ways. Margarita (not her real name) said it took her years to muster up the courage to divorce her husband because she was scared her friends and family from Mexico would find out and she was sure “they wouldn’t support me.” And Catalina said her family “think[s] I am the shame of the family because I am divorced… They accuse me. They said, ‘how did you do this?’ Even my mother, who knew about the abuse for all these years.”

Although these stories clearly show that social networks do not always support and encourage women to protect their physical and emotional safety, it is important to complicate the notions of well-being in these women’s lives and to recognize the context in which advice is offered by friends and family. Understanding these women in the context of their political, economic, and social experiences demands a broader approach to those questions of staying and leaving the relationship. Leticia, for example, explained that her friend’s advice “not to leave him” was based on the fact that “she knew it was too difficult to further myself without being documented” and because “I didn’t know anything or anyone. I depended solely on him.” Ana’s situation was similar; when asked what her friends advised her to do in response to the abuse, she said, “They wanted me to stay here in the US, so they understood I had a problem.” Roberta told me that her family was sad when she left her abusive husband because they believed it would be too hard and too lonely for her to be single and undocumented.

Parents, relatives and friends may act to enable the abusive relationship out of genuine concerns about the woman’s economic sufficiency, legal vulnerability, and cultural literacy. And it is this layer of politically imposed marginality and insecurity which neither literatures fully takes into account.

The problem in the dominant social networks discourse on immigrant adaptation may not be limited to the nature of the qualitative generalization being made, but rather resides in the very attempt to make qualitative statements about immigrants without considering immigration as a legal, social and political process.

Simply put, immigrant families and networks may not be essentially different from any other families and networks. The only thing specific or essential about immigrant networks may be the immigration itself—the entitlements and identities that are created by the immigration process and the state. In fact, what distinguishes these undocumented immigrant women’s experiences and relationships and warrants specific attention might not be anything essential about them, but rather the way they are influenced and constrained by the legal and social context in which they are set.

The diversity of social arrangements and personal relationships among the women interviewed attests to the fact that immigrant social relationships are not characterized by innate characteristics of immigrants as individuals, but rather by the common outcomes of socially imposed legal entitlements, political exclusions and social attitudes. Carefully considering these women’s experiences in their intimate relationships reveals that they are inextricably bound to their legal entitlements as undocumented immigrants. The thesis details how gender biases in federal immigration laws have intensified women’s dependency on their husbands and played into abuse in their marriages, how changes in federal funding regulations for legal services attorneys have deterred women from following traditional prescriptive paths for recovery from domestic violence, how changing drivers license laws have hindered women from conceiving of themselves as public actors and limited their possibilities for self-sufficiency, and, even how national security measures have affected the experience of grieving for dying relatives.

All of these legal, political and institutional processes and practices shape the realities of these women’s lives in surprising and myriad ways which are largely unacknowledged by the dominant discourses. Understanding their lives and experiences demands critical attention to macrostructural processes and the complex ways in which they filter into experience.

Thus, there is a need for more critical and rigorous analyses of the social and political forces that shape immigrants’ lives and often deny them their basic human rights. Beyond all else, these women’s voices and stories reveal that law is not just additive, but formative. It does not just constrain or empower its subjects; it also creates them.

Fall 2003, Volume III, Number 1

Margot Mendelson graduated from Harvard in 2003 with a self-designed major in Peace & Conflict Studies. She is currently living in Costa Rica and working at a human rights organization. She hopes to pursue a career advocating immigrant rights and, more immediately, to find a publisher for the full version of her thesis.

Related Articles

Human Rights: Editor’s Letter

During the day, I edit story after story on human rights for the Fall issue of ReVista. During the evening, I work on my biography of Irma Flaquer, a courageous Guatemalan journalist who was…

ONGs en América Latina y los derechos humanos

Las ONG ofrecen mil modos de recordar la dignidad humana a los gobiernos y las sociedades. Las dos experiencias que esbozo en esta nota reflejan algunas de las estrategias asumidas por…

Peru’s Human Rights Coordinating Committee

The human rights abuses that devastated Peru from the early 1980s to the mid 1990s are once again an issue of debate in that country with the release of the Peruvian Truth and Reconciliation’s…