The Legacy of Sylvia Molloy

Photo by Lagniappe Studio

One of the most fascinating aspects of Sylvia Molloy’s work is her challenge to the traditional conventions of identity. Molloy holds a singular perspective on writing, seeing it as a process through which we can reconstruct ourselves from memories turned into words. Throughout her first novel, En breve cárcel (1981), the protagonist immerses herself in a deep introspection, questioning her past and present identity through the prism of the written word. For Molloy, writing is not merely a means of preserving memory; it is a powerful tool for the reconfiguration of a fragmented voice. This voice, which is developed and composed in writing, must finally be destroyed at the conclusion of the novel, returning the writer to the solitude of having her textual embodiment stripped away.

Writing is also a tool for reconstructing a voice. Every act of writing, like life itself, depends on a journey, on exploring unknown territories to return to the place of writing, where the collected fragments are assembled and recomposed. We cannot precisely determine the origin of the voice we read, since those origins change and the traces of our displacement in search of them define us. We can assert that Molloy’s novel is a good example of how we create our own language from the scars left in our memory by engaging with and failing to engage with other voices, with other bodies.

As the one who observes “she” writing says: “She is grateful for the undulating letter that links her, she recognizes the scars of a body that caresses. Body and sentence break again, but not in the same scar” (67). It is this progressive tearing, alternating with patches or threading, what Molloy’s novel stages, it is that which is lost within us, something that is alien and fleeting, and when it wants to emerge, it does so clothed in our own traces: this is how “she” emerges in the novel. This tearing is repetitive, but neither the wound/print nor the scar/thread that it attempts to remedy is ever repetitive.

Thus, the act of writing becomes a constantly evolving forge of identity, challenging conventional notions and drawing on the diversity of human experiences and emotions. In fact, in her interviews and lectures recorded in her later years, Molloy uttered some revealing phrases about her relationship with writing: “reality is what one writes” and “my fiction is a bag of scraps”. Her statement, “I have a sense of knowing myself in writing: that’s me,” encapsulates the essence of her work and her explorations of the construction of identity through writing. The novel begins with “she” (the one who writes) surrounded by scraps, pieces, scraps, scraps, pichinchas. The blank page, once scarred of letters, is the place of provisional unification of these loose pieces, of these fragments of herself and others: it is the space of construction of her body, of a mask that allows her to be seen/read/heard.

In Sylvia Molloy’s work, the writing process becomes a fascinating journey connecting the construction and destruction of identities: the novel’s protagonist immerses herself in her memories, doubting and scrambling them in an effort to lessen the pain of waiting.This construction resembles the molding of an ephemeral and changeable identity, later to be peeled off once described.

Writing is initially presented as an act of revenge, giving rise to desire. However, this perception evolves as the protagonist reflects on the ancient act of Erostratus, who set fire to the temple of Artemis in search of notoriety and being remembered. This fusion between the preservation and destruction of memory shows us the complexity of Molloy’s narrative voice, which emerges from scraps and fragments. The narrative becomes an iconoclastic act, where “she” must be consumed by the flames, leading the reader to question the very nature of identity and writing, which are, like the temple of Artemis, ephemeral and susceptible to destruction.

After remembering to make an image of “herself,” the protagonist (almost reaching the level of the person who pronounces, “her too”) reflects on the temple of Artemis that went up in flames in 356 BC. The separation between “her” and “her also” is seen in the context of that reflection: the author is, at the same time, the image that she made of herself and the iconoclast who incinerates the temple that created the writing. Erostratus, one of antiquity’s infamous characters, was a little-known shepherd who wanted posterity to remember him. Confronted with the question, “How can I be remembered?,” he came upon the answer in an iconoclastic act that echoes through time—setting fire to the grandiose temple of the goddess Artemis in Ephesus. This episode, from a general perspective, boils down to the idea of committing extreme acts to achieve notoriety. When we analyze the action of Erostratus in the context of Molloy’s novel, it reveals itself as a fusion between the preservation of memory and destruction. The author perceives the narrative voice as one that emerges from the gathering of scraps: this word implies shattering. Can ashes be considered as fragments? If we adopt a permissive perspective, we could answer positively, but an image’s incineration means the fragments that make up the icon can no longer reassembled the same way. Thus, “she” must be consumed by the flames, since the fragments that, spun together through words, gave rise to a mask through which it (the novel) could be seen, reduced to dust and carried off by the wind that caresses its pages.

En breve carcel also makes us ponder the paradox of writing and the destruction of images. Just as Erostratus sought notoriety through the destruction of the temple of Artemis, the protagonist of the novel seeks immortality through writing, but this immortality requires the constant destruction of the image that is constructed. Writing becomes an iconoclastic act, in which words are the flames that consume the former textual identity. This idea challenges conventional notions of identity and writing, inviting the reader to reflect on the ephemeral nature of both and the possibility of constant reconstruction. Ultimately, Molloy shows us that defining ourselves should not be synonymous with caging ourselves in what we pronounce about ourselves, and that the destruction of images can be a liberating way to seek a more authentic and fluid identity.

Before deciding to incinerate her image, before giving her own version of her father’s dream (the order of her dreamlike father), “she” has operated a change in the narrative. This becomes clear when she describes the long-awaited meeting with Vera, which she had been dreading for a long time when she began to write; remember that at the beginning of the novel, when she was preparing to write/wait for Renata, we are told that “[Vera’s story] delighted in itself, skin that had succeeded in composing itself” (22). “She” judged Vera’s narratives as self-possessed and certain that they were Vera herself, there would be no scars on the skin of that narrative mask: “she” envied that certainty of “I” that Vera’s narratives carried. Nevertheless, when at last there is “the encounter she had furiously desired, whose imagination had finally bored her, it happened without an author. That is to say, it happened without the authority she would have wanted to give it: her own” (126). Up to that moment the encounters were shuffled from the work she did relating her memories, creating Vera and Renata’s faces… Vera, “the real one,” appears as an insipid mimic of the apotheosis Vera about whom “she” fantasized, remembering and anticipating her. “Her” Vera is much richer in facets, to the point that when she appeared in reality, “she” was already bored with imagining her. What she does with her image (setting her on fire) a few pages later, near the end, is what she is satisfied to be able to do after the writing with Vera’s image: “I wanted to compose an image of Vera forever, to fix it, complete in his memory, and then keep it or discard it: store it in a place of his, which he controls and to which he may not return, but store it in its entirety” (127). In the end, immobility, inflexibility, solidification are the death of imagination, the death of passion and even of any desire for revenge. “She” destroys her image as an inapprehensible spirit escaping from a statue in which she was imprisoned, she has covered herself with layers of words to harden the crust that she then destroys to run to be alone, mobile.

Las Huellas de Sylvia Molloy

Por Sebastián Cadavid y Jeffrey Cedeño Mark

Foto por Lagniappe Studio

Uno de los aspectos más fascinantes de la obra de Sylvia Molloy es su desafío a las convenciones tradicionales de la identidad. Molloy sostiene una perspectiva singular sobre la escritura, considerándola como un proceso mediante el cual podemos reconstruirnos a partir de los recuerdos convertidos en palabras. A lo largo de su primera novela, En breve cárcel (1981), la protagonista se sumerge en una profunda introspección, cuestionando su identidad pasada y presente a través del prisma de la palabra escrita. Para Molloy, la escritura no es meramente un medio de preservar la memoria, es una herramienta poderosa para la reconfiguración de una voz fragmentada. Esta voz, que se desarrolla y se compone en la escritura, debe finalmente ser destruida al concluir la novela, devolviendo a la escritora a la soledad de haberse despojado de su encarnación textual.

La escritura es también una herramienta para reconstruir una voz. Cada acto de escritura, al igual que la vida misma, depende de un recorrido, de explorar territorios desconocidos para regresar al lugar de escritura, donde se ensamblan y recomponen los fragmentos recolectados. No podemos determinar con precisión el origen de la voz que leemos, ya que esos orígenes cambian y las huellas de nuestro desplazamiento en su búsqueda nos definen. Podríamos afirmar que la novela de Molloy ejemplifica cómo creamos nuestra propia lengua a partir de las cicatrices que deja en nuestra memoria el encuentro y desencuentro con otras voces, con otros cuerpos.

Como dice la que observa a “ella” escribir: “Agradece la letra ondulante que la enlaza, reconoce las cicatrices de un cuerpo que acaricia. Vuelven a romperse cuerpo y frase, pero no en la misma cicatriz” (67). Es este desgarramiento progresivo, alternado con remiendos o hilvanaciones, lo que escenifica la novela de Molloy, es eso que se pierde en nuestro interior, algo que es ajeno y fugaz, y al querer emerger, lo hace revestido de nuestras propias huellas: así surge “ella” en la novela. Este desgarramiento es repetitivo, pero nunca lo es la herida/huella ni la cicatriz/hilo que lo intenta remediar.

En este contexto, el acto de escribir se convierte en una forja de identidad en constante evolución, desafiando las nociones convencionales y nutriéndose de la diversidad de experiencias y emociones humanas. De hecho, en sus entrevistas y conferencias registradas en sus últimos años, Molloy pronunció algunas frases reveladoras sobre su relación con la escritura: “la realidad es lo que uno escribe” y “mi ficción es una bolsa de retazos”. Su afirmación, “tengo una sensación de conocerme en la escritura: esa soy yo”, encapsula la esencia de su obra y sus exploraciones sobre la construcción de la identidad a través de la escritura. La novela comienza con “ella” (la que escribe) rodeada de retazos, pedazos, desechos, pichinchas. La hoja en blanco, una vez cicatrizada de letras, es el lugar de unificación provisional de estos trozos sueltos, de estos fragmentos propios y ajenos: es el espacio de construcción de su cuerpo, de una máscara que le permita ser vista/leída/escuchada.

En la obra de Sylvia Molloy, el proceso de escritura se convierte en un viaje fascinante que conecta la construcción y destrucción de identidades: la protagonista de la novela se sumerge en sus recuerdos, dudando de ellos y revolviéndolos en un intento por mitigar el dolor de la espera. Esta construcción se asemeja a la forja de una identidad efímera y cambiable, que será posteriormente despellejada una vez descrita.

La escritura, en sus primeros pasos, se presenta como un acto de venganza que da lugar al deseo. Sin embargo, esta percepción evoluciona a medida que la protagonista reflexiona sobre el antiguo acto de Eróstrato, quien incendió el templo de Artemisa en busca de notoriedad y recuerdo. Esta fusión entre preservación de la memoria y destrucción revela la complejidad de la voz narrativa de Molloy, que surge de retazos y fragmentos. La narración se convierte en un acto iconoclasta, donde “ella” debe ser consumida por las llamas, llevando al lector a cuestionar la naturaleza misma de la identidad y la escritura, que son, al igual que el templo de Artemisa, efímeras y susceptibles a la destrucción.

Tras recordar para hacerse una imagen de “ella” misma, la protagonista (casi alcanzando a quien la enuncia: “ella también”) reflexiona sobre el templo de Artemisa que fue incinerado en el 356 a.C. La separación entre “ella” y “ella también” se percibe a partir de esa reflexión: la autora es, a la vez, la imagen que de ella erigió y el iconoclasta que incinera el templo que levantó la escritura. Eróstrato, personaje infame de la antigüedad, fue un pastor de escaso renombre que ambicionaba ser recordado por la posteridad. Ante la pregunta: ¿cómo hago para que me recuerden? Su respuesta se tradujo en un acto iconoclasta que resuena a través del tiempo: incendiar el grandioso templo de la diosa Artemisa en Éfeso. Este episodio, desde una perspectiva general, se reduce a la noción de cometer actos extremos con el propósito de alcanzar notoriedad. Cuando analizamos la acción de Eróstrato en el contexto de la novela de Molloy, se revela como una fusión entre la preservación de la memoria y la destrucción. La autora percibe la voz narrativa como una que surge de la reunión de retazos: esta palabra implica despedazamiento. ¿Pueden considerarse las cenizas como fragmentos? Si adoptamos una perspectiva permisiva, podríamos responder afirmativamente, pero la incineración de una imagen implica que los fragmentos que componen el ícono ya no pueden ser reunidos de la misma manera. Así, “ella” debe ser consumida por las llamas, ya que los fragmentos que, hilados por medio de la palabra, dieron vida a una máscara para que pudiéramos contemplarla (la novela), se reducirán a polvo y serán llevados por el viento que ha rozado sus páginas.

En breve cárcel también nos lleva a considerar la paradoja de la escritura y la destrucción de imágenes. Así como Eróstrato buscaba notoriedad a través de la destrucción del templo de Artemisa, la protagonista de la novela busca la inmortalidad a través de la escritura, pero esta inmortalidad requiere la constante destrucción de la imagen que se construye. La escritura se convierte en un acto iconoclasta, donde las palabras son las llamas que consumen lo que una vez fue la identidad textual. Esta idea desafía las nociones convencionales de la identidad y la escritura, invitando al lector a reflexionar sobre la naturaleza efímera de ambas y la posibilidad de reconstrucción constante. En última instancia, Molloy nos muestra que definirnos no debe ser sinónimo de enjaularnos en lo que pronunciamos sobre nosotras mismas, y que la destrucción de imágenes puede ser una forma liberadora de buscar una identidad más auténtica y fluida.

Previo a esta decisión de incinerar su imagen, antes de versionar el sueño de su padre (la orden de su padre onírico) a su antojo, “ella” ha operado un cambio en el relato. Esto se hace patente cuando describe el encuentro con Vera, mucho tiempo esperado y al que le temía sobremanera al empezar a escribir; recordemos que se nos decía al comienzo de la novela, cuando se disponía a escribir/esperar a Renata, que “[El relato de Vera] se deleitaba en sí mismo, piel que había logrado componerse” (22). “Ella” juzgaba las narraciones de Vera como dueñas de sí mismas y seguras de que eran Vera misma, no había cicatrices en la piel de esa máscara narrativa: “ella” envidiaba esa certeza de “yo” que cargaban los relatos de Vera. No obstante, cuando por fin se da “el encuentro que ella había deseado con furia, cuya imaginación por fin la había aburrido, se dio sin autor. Es decir, se dio sin la autoridad que ella hubiera querido darle: la suya” (126). Hasta ese momento los encuentros fueron barajados a partir del trabajo que hizo relatando sus recuerdos, confeccionándole rostros a Vera y Renata… Vera, “la real”, aparece como un remedo insulso de la Vera apoteósica con la que fantaseó “ella”, recordándola y anticipándola. La Vera de “ella” es mucho más rica en facetas, al punto de que cuando apareció en realidad, “ella” ya estaba aburrida de imaginarla. Lo que hace con su imagen (incendiarla) unas páginas después, cerca del final, es lo que le satisface poder hacer tras la escritura con la imagen de Vera: “Quería componer para siempre una imagen de Vera, fijarla, completa en su memoria, para luego conservarla o desecharla: almacenarla en un lugar suyo, que controla y al que acaso no vuelva, pero almacenarla entera” (127). Al final, la inmovilidad, la fijeza, la cristalización, son la muerte de la imaginación, la muerte de la pasión y hasta de cualquier deseo de venganza. “Ella” destruye su imagen como inaprensible espíritu que escapa de una estatua donde penaba aprisionada, se ha cubierto de capas de palabras para endurecer la corteza que después destruye para correr a ser sola, móvil.

Sebastián Cadavid holds a Master’s degree in Literature from the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá.

Sebastián Cadavid es Magíster en Literatura de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá.

Jeffrey Cedeño Mark is a professor in the Literature Department of the Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá.

Jeffrey Cedeño Mark es profesor del Departamento de Literatura de la Pontificia Universidad Javeriana, Bogotá.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

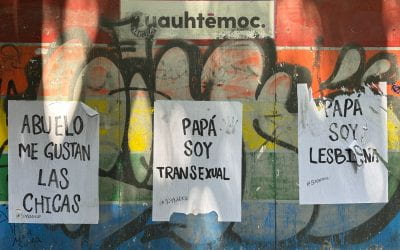

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.