The Ongoing Body

Transing The Cancellation of Latinidad

Back in February 2023, I attended a scintillating workshop with AfroIndigenous artist and scholar Alán Peláez López for their featured exhibit “N[eg]ation.” Their work centers imaginaries: futures not yet tangible, concentrating on the bonds and togetherness of trans+ people and using art to stir intersectional emotions. Trans+ people, those trans, genderqueer, intersex, nonbinary, and Two Spirit and largely identifying differently than the often-forced male or female of visible genitalia at birth, exist in an in-between that challenges normative expressions that limit existence outside of male and female expectations. As a formerly undocumented person experiencing Blackness in Latin America and the United States, Pelaez Lopez effectively evokes this in-betweenness.  As a trans and disabled person, I rarely have the privilege to think of futures. Trans+ people are so often only deemed notable in death and as a political headline, and disabled people in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic have been told in violent fashion that they matter less as they advocate for basic protections and the able-bodied masses fail to protect them. I do not see trans+ elders or disabled elders very often, let alone at that intersection, making it difficult to imagine myself older than I am. Entering a space where challenges are many, but futures abound, provided me an opportunity to recognize my own privilege, and situate it in critical discussion with futures for the first time. Rarely do we examine intersectionality in such a thoughtful way.

As a trans and disabled person, I rarely have the privilege to think of futures. Trans+ people are so often only deemed notable in death and as a political headline, and disabled people in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic have been told in violent fashion that they matter less as they advocate for basic protections and the able-bodied masses fail to protect them. I do not see trans+ elders or disabled elders very often, let alone at that intersection, making it difficult to imagine myself older than I am. Entering a space where challenges are many, but futures abound, provided me an opportunity to recognize my own privilege, and situate it in critical discussion with futures for the first time. Rarely do we examine intersectionality in such a thoughtful way.

When bodies travel from Latin America to the United States, they are relegated to the identifier of Latinidad: no longer Mexican, Guatemalan, Colombian, Brazilian, simply “Latin.” This, precisely, is cause for cancellation of Latindad in and of itself: it is not an accurate nor specific metric of identity, but simply a whitewashed conglomerate vocabulary. As Peláez López points out in “The X In Latinx Is A Wound, Not A Trend” (2018), four wounds emerge from this vocabulary, that of anti-Blackness, settler colonialism and anti-Indigeneity, femicide, and the inarticulable. While Peláez López does not center transness as the exclusive underpinning to their work, it becomes immediately visible in each of the four wounds. The challenges to cisheteronationalism— the nation-driven ideals of cisgenderism and heterosexuality and identifying as expected cis and straight from birth to death— are manifested in Peláez López’s work when approached methodologically.

The act of transing, or transness as a verb and a movement, as method does indelibly link two highly-politicized marginalized movements and changings of bodies and spaces: that of gender transition and that of immigration, and positions a contrast to the expected static of identities. This reveals the underpinning of white supremacy and its tools of cisheteronationalism and the ability to be mobile within and against those constraints as a necessity for survival. Transing as method uncovers the constant micro movements that become macro shifts – that bodies are variable and ever changing – thus, in order to construct coalitions, change and development must be underpinned. The transing of any body from the Latin American context to the U.S. context is unique. The act of transing our approach is not just a theoretical exercise. Anti-trans rhetoric spikes in the last few years provide a unique lens by which to consider xenophobia in the U.S. context and positionality with transing as method.

While transing as method could be applied to any movement of any body between contexts across the globe, the symbolic similarities with the trans experience and the Latin American context are not random. They are the result of the nature of removing a body from its origin to a context with seemingly greater opportunity, while existing in white supremacist cultures and frameworks. By homogenizing Latinidad and the gender binary that exists in the Latin American and U. S. context, we are erasing the former body—the Mexican, Colombian, Black, Indigenous, Trans, Feminine—as well as the transition itself, culminating into the reductionary state of Latinidad or the reduction to a single and permanent gender identity. Identities are not static: the chronology of transness fixes bodies only in a challenge to the white-supremacist state. We then are offered the opportunity to examine challenges to linear temporality and excision of past identity through the lens of transness. Latinidad must be canceled, as Alán Pelaez Lopez called for in 2018, referencing the four wounds that scar and heal, but do not erase as white supremacy assumes they would. Thus, transing is an appropriate method by which to begin to capture the nuance of the immigrant experience, especially when one has not experienced it firsthand, because we return autonomy and process to a de-emphasized body and question the status of identities and boxes ascribed to them.

Terms like “trans,” “transgender” and “transition” have had no shortage of media presence in recent years, often with a negative connotation. Trans people are being criminalized through legal workarounds on banning drag and therefore anything deemed as “crossdressing” in the legal sense. We have lost, at the legislative level, the fluidity and self-determination that is essential to understanding transness. I use trans+, modeled after LGBTQ+, to, in a small way, return that fluidity and self-determination to nonbinary, Two Spirit, genderqueer, and intersex siblings who identify with our struggles and our joy without necessarily claiming the trans label.

Trans imaginaries have been a crucial element to the survival of trans bodies since the dawn of community organizing in the United States, led by trans women of color like Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera. Cisgender people often view transition, and the trans work of Marsha P Johnson and Sylvia Rivera, as a moment in time, and coming out as a singular event: a social media post, public announcement, or surgical makeover. While it may be so for those of us that come out in one culminating social media post, those people will still have to come out to new people and new environments for the rest of their lives. Benchmarks like name changes, hormonal transition and surgical transition that trans people may experience, often happen over years or even decades depending on access and want. In reality, we exist in a constant state of transition, a symbiosis with our environments, to adapt and attempt to find the most joyous expression and experience of self. There are no end-points, and there is no such thing as a “complete” transition. At the first annual Harvard Trans+ Community Celebration in 2022, we heard from trans+ elders that transition “never ends.”

Transness is a progression, an experience, and an ongoing movement. “Trans” is a prefix denoting “across, over, or beyond.” Transing as method serves the same goals: depicting the metaphorical and literal crossing of borders, transcending geographical, political, and scientific constraints and enlightening discourse of the movement of bodies, cultures, and knowledge in symbiosis with the environment. There are no tangible end points to the movement of bodies transnationally, similarly to trans bodies, even if there are notable inflection points. Thus, in the Latin American context, transing as method allows us to better conceptualize the perceptions and experiences of bodies transnationally, centering the experiences of immigrants now existing in the American space.

While trans bodies serve as an analogy for bodies moving transnationally, this is not an arbitrary overlap of words because of the ways bodies are regulated in their movement within and between environments. Bodies moving transnationally are moving largely intentionally, although perhaps not exclusively. Do not confuse this with the internal pressure to exist in an alternative context for a myriad of reasons, as this is theoretically analogous to transness. Some bodies are trafficked and forcibly moved, which can only be metaphorically modeled in intersex communities where notions of cis-ness are at times medically forced upon unconsenting children.

Conservative rhetoric attempts to anti-trans the body and maintain it in intangible ideologies of cis-ness are constant, even attempting to ban caricatures of that cis-ness by attacking drag and other art forms. In these rhetorics, the literal movement of bodies is juxtaposed: trans bodies unfit to reside are asked to “go back where they are from” for not assuming the expected gender and positionality and bodies transing simultaneously are told to “leave if you don’t like it,” asked to return to not only a nation, but a body, neither of which meeting the needs.

The reverse is also true—bodies transing borders are pushed to return, and trans bodies being held to cis standards are encouraged to leave state and national bodies if they are not welcome. Bodies moving transnationally in immigration are moving in the rhetoric “assigned” to transness, only to be relegated to xenophobia on arrival in the United States. This brings up the discussion of home. What does it mean to have a home? Not simply a house or residence, but a home. Home involves community, security and belonging: the progression of the body to physical home, and the emotional longing of home in a trans body.

Trans bodies are a challenge to the attempted homogeneity and erasure of Indigeneity and Blackness by way of white supremacist and eurocentric conceptions of Latinidad. Mexico, for example, fostered a eugenicist rhetoric in the early 20th century that highlighted the “ideals” for bodies: a mix of the “best” qualities of Indigenous and European peoples, an assimilationist body that notably and intentionally excluded Black and Asian bodies. Any challenge to the ideal of an able bodied, cis, straight, racially ambiguous white-approaching body served as a challenge to not only eugenicist policies, but therefore the state itself. Latinx trans bodies continue to do just that across Latin America and the United States, with those same eugenicist ideals as strong as ever. Additionally, as shown clearly in anti-immigrant rhetoric in the United States, immigrant bodies are a challenge to the eugenicist and white supremacist American narratives. These denaturalizing and dehumanizing homogeneities provide a lens for analogy.

In a group reflection of poetic works led by Alán Pelaez Lopez, community members and Latinx studies students examined our intimate emotional reactions and our own writing. Bubbling to the surface, it became clear that at the deepest points, my trans imaginaries were inseparable from my disabled body and the fear chasing me as someone challenging the body politics around me. Transness, shared by many others in the room, became the lens and method through which I could begin to parse how my disabled body was being received in the world, and how that made me feel. I wrote, “every year I find out how lucky I am and how hidden my unluckiness is. And every year I find out how to love that unluckiness better, more wholly, more visibly, and more honestly”. The ways in which our bodies move and are received by the world around us are inseparable and undeniably intersectional. For me, it is my transness and my disabilities that define and underlay every thought, movement, and space I occupy. In the futures I imagine, transness is not only an identity, but a recognition of the movement of bodies, visibly and invisibly. By moving beyond identity, transness becomes method.

In a group reflection of poetic works led by Alán Pelaez Lopez, community members and Latinx studies students examined our intimate emotional reactions and our own writing. Bubbling to the surface, it became clear that at the deepest points, my trans imaginaries were inseparable from my disabled body and the fear chasing me as someone challenging the body politics around me. Transness, shared by many others in the room, became the lens and method through which I could begin to parse how my disabled body was being received in the world, and how that made me feel. I wrote, “every year I find out how lucky I am and how hidden my unluckiness is. And every year I find out how to love that unluckiness better, more wholly, more visibly, and more honestly”. The ways in which our bodies move and are received by the world around us are inseparable and undeniably intersectional. For me, it is my transness and my disabilities that define and underlay every thought, movement, and space I occupy. In the futures I imagine, transness is not only an identity, but a recognition of the movement of bodies, visibly and invisibly. By moving beyond identity, transness becomes method.

Kris King, Harvard College Class of 2024, is Executive Director of TransHarvard, where Alán Peláez López will be featured on October 7.

Related Articles

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

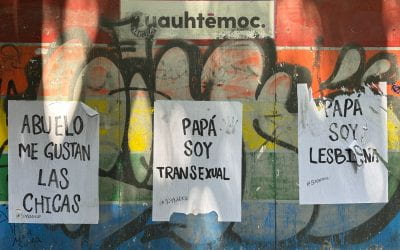

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.