The Pandemic in Venezuela

Challenges and Side Effects

Latin America is the world’s epicenter of Covid-19, with more than 10 million cases and 400,000 deaths as of November 1. The region’s countries have nine of the world’s 16 highest mortality rates per 100,000, with Peru claiming the dubious distinction of the highest rate after the microstate of San Marino. Meanwhile, despite accusations of government undercounting, Brazil (159,884) and Mexico (91,753) rank second and fourth globally in total number of deaths. The region is reeling from overburdened health systems, deteriorating economic conditions, and uncertainty.

The crisis has also had a troubling effect on the region’s politics, especially in non-democratic places, as already authoritarian countries have become even more restrictive. This, in turn, has made life increasingly difficult for the majority of people who live there, exacerbating the human and political costs of the pandemic. No place is this clearer than in Venezuela.

Although I live in Washington, DC, I have seen these costs from afar. My wife’s family lives in the cities of Caracas, Valencia and San Cristóbal, Venezuela, where relatives try to muddle through a pandemic on top of an economic and humanitarian crisis. The country’s authoritarianism has exacerbated the secondary effects of the pandemic and made daily life even more challenging than it already was.

The erosion of liberties

To begin, the pandemic has provided cover to leaders who wish to reduce civil liberties, undermine checks and balances, and even electoral freedoms. According to both Freedom House and the Varieties of Democracy Project (VDem), global democracy has grown weaker since the beginning of the coronavirus pandemic. However, backsliding is not uniform: stronger democracies have shown themselves to be more resilient than weak ones or highly repressive states, where authoritarian leaders have undermined weak safeguards against the abuse of power. This pattern has been borne out in Latin America: more robust democracies, such as Uruguay and Costa Rica, have witnessed fewer violations of citizens’ rights, while leaders in El Salvador, Nicaragua, and Venezuela have curtailed electoral freedoms, checks and balance, and especially civil liberties.

In Venezuela, Human Rights Watch has written extensively about how state security forces have used pandemic lockdown measures as an excuse to crack down on dissenting voices and intensify their control over the population. As in other countries, political leaders used the pandemic as a pretext to block independent news sites and arrest individuals on spurious charges, such as political scientist, blogger, and political commentator Nicmer Evans, who was detained in July 2020. The government has also reportedly mistreated returning migrants, detaining them in improvised “containment centers” in an effort to protect the country from Covid-19.

These measures have institutional justification. On March 13, President Nicolás Maduro decreed a state of “emergency and alarm” at the national level, establishing measures to limit the spread of Covid-19, including restrictions on movement, suspension of certain activities, and mandatory use of face masks. The decree authorizes security forces to carry out “inspections” whenever “they deem necessary,” if there is a “reasonable suspicion” that someone is violating the measures established in the decree. Maduro has continued to extend this state of emergency without approval from the opposition-led National Assembly, exceeding the Constitutional 60-day limit.

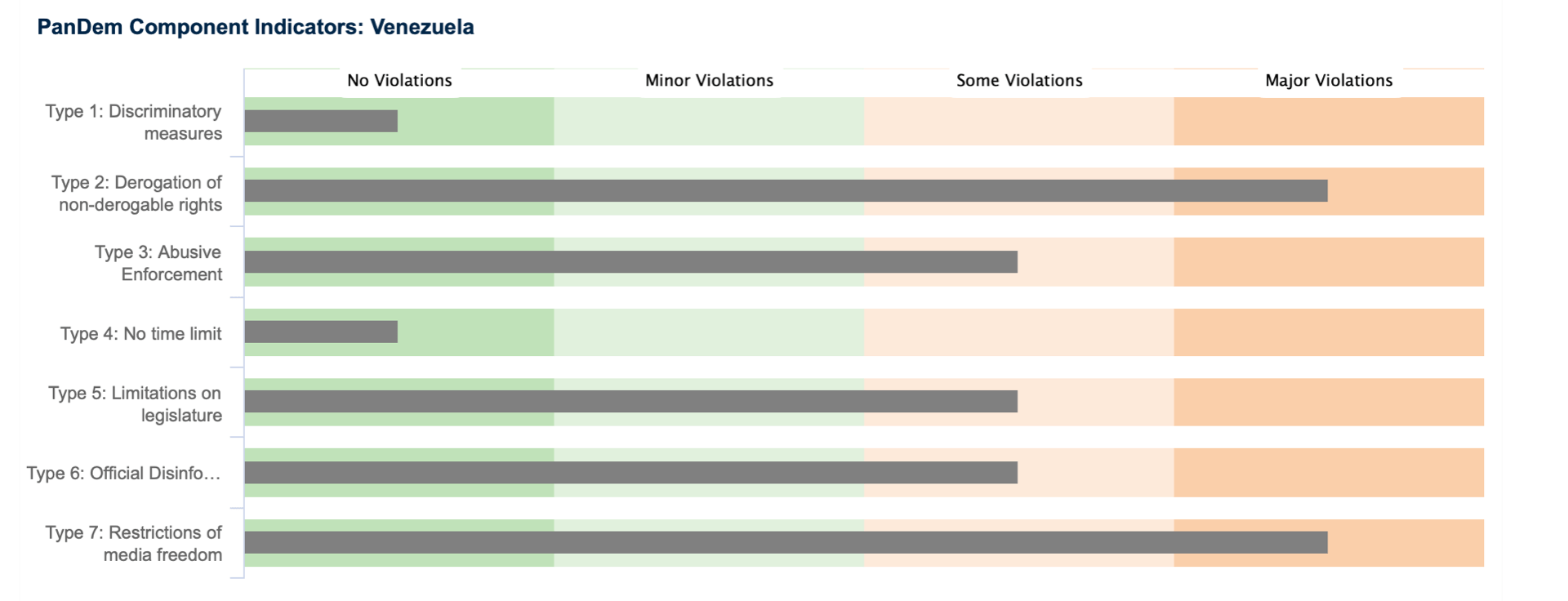

A special report from VDem on democratic backsliding under the pandemic finds that, overall, the Venezuelan government has committed major violations of rights. As the table shows, Maduro has further restricted media freedom and overseen the derogation of non-derogable rights contained in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights.

Source: “Pandemic Backsliding: Democracy During Covid-19 (PanDem)”, Version 4. Varieties of Democracy (V-Dem) Institute, www.v-dem.net/en/our-work/research-projects/pandemic-backsliding/

Pandemic life in dictatorship

While government responses across the globe have necessarily made daily life more difficult, disrupting work patterns, school, shopping, and social interactions, these effects are far worse for people living under dictatorship.

I’ve noticed at least four developments with my wife’s family in Venezuela:

- A decline in the (already poor) quality of life for a population already suffering from unreliable basic services.

- The spread of fake coronavirus cures on social media as a result of the lack of official information and government transparency;

- Reticence to trust authorities or health professionals—like Cuban doctors—given a lack of trust in the state;

- A decrease in access to resources for a desperate population due to the closed border.

First, my wife’s family reports that their quality of life has continued to decline, as pandemic restrictions force many people to stay indoors. However, poor infrastructure and unreliable basic services makes these stay-at-home orders unbearable for many. Rolling blackouts are the norm for much of the country, as well as propane gas shortages for cooking, and slow internet (Venezuelans suffer from the second-slowest internet in the hemisphere, after Cuba). I informally track the blackouts in San Cristóbal by the WhatsApp pings on my wife’s phone. Usually, a long stretch of unanswered messages means a blackout, while a burst of messages means service has been restored. While we complain of “Zoom fatigue” in the United States, unreliable internet service means that my in-laws do not even enjoy wireless service.

Second, the nature of access to information under dictatorship can also be dangerous.When leaders like Donald Trump or Jair Bolsonaro of democratic countries suggest hydroxychloroquine or other unproven treatments for Covid-19, health advisors, governors and the media can push back against these claims and inform the public. But this is less likely to happen in Venezuela, where Maduro has declared both hydroxychloroquine and an herbal tea to be effective remedies for Covid-19—and also made the false claim that Venezuelan doctors have developed a cure for the virus. These outrageous and dangerous claims go unchallenged.

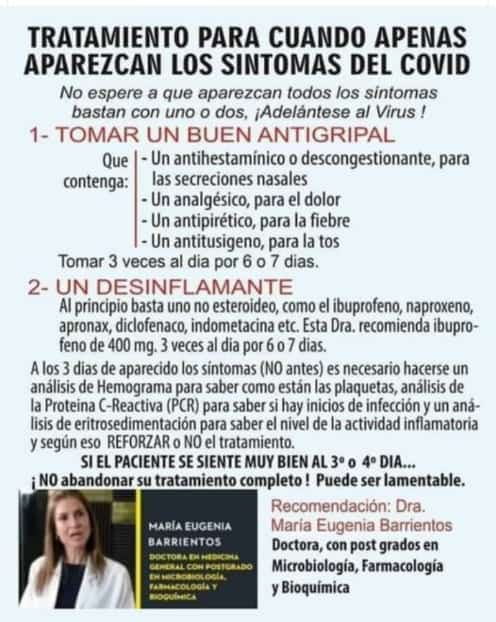

Lack of a free press also means that pandemic information has migrated online to WhatsApp and Facebook. I collected screenshots of some of the health memes that family members have passed around regarding Covid-19. The first piece of misinformation, from WhatsApp, describes measures and medicines to take in order to combat the virus (never mind that many carriers are asymptomatic and that tests are not widely available or administered).

The second, from Facebook, is a regiment of vitamins “administered in hospitals,” egg flour, water and rest that can be given at home to treat the virus.

Lastly, a screencap of a Covid-19 denier video in which an angry man—perhaps a lawyer, as the title indicates, but perhaps not—recounts conspiracy theories about the “true” origins of Covid-19 and beseeches lawyers to sue the World Health Organization. A free press and transparent public communication from the government would mitigate or neutralize this sort of potentially damaging misinformation.

A third development is an unwillingness to seek out medical attention. This is borne of shoddy medical care, poor public hospital conditions, and especially a distrust of Cuban health workers among members of the political opposition. For my wife’s family, it is also deeply personal. In 2017, my compadre, my wife’s cousin by marriage, was gunned down in the city of Mérida. He survived the shooting, was taken to a clinic but eventually passed away due to avoidable complications, leaving behind a widow, two children and an extended family that is still grieving. As you can imagine, circumstances would have to be exceptional for anyone in my wife’s family to go to a hospital in 2020.

Broad swaths of the population also distrust government health workers. In San Cristóbal, the local government sent Cuban health workers to administer a voluntary Covid-19 test, but everyone in the community, distrustful of people seen as agents of the Cuban government or politicized emissaries of Maduro, turned down the voluntary nasal swab and asked the medical brigade to leave. I could have predicted this outcome. Below is a screencap from Facebook of a widely shared September 2020 article in the PanAm Post that quotes Carlos Vecchio, Juan Guaidó’s ambassador to the United States, denouncing Cuban medical workers in Venezuela as nothing more than an undercover intelligence operation. There is no state worker my in-laws would trust less.

Lastly, and tragically, closed borders to prevent the transmission of Covid-19 between countries have made it more difficult for Venezuelans living in western and southern states to find food and other products. My in-laws and their relatives in Táchira traveled to Cúcuta, Colombia, every couple of weeks when the border was open in order to buy food that is too costly or unavailable in Venezuela (they even crossed the trochas when the border was closed in 2019, although that has now become too dangerous). Given this additional hardship, my wife helps make grocery purchases from abroad, allowing some in her family to eat. Of course, not everyone has someone abroad willing and able to buy them food.

The tragic thing is that this isn’t just “our sad story”—it’s the life of millions of Venezuelans who used to make up that country’s middle class. Maybe the worst part is that these are just observations that my wife and I see from Washington, DC. My wife’s family certainly doesn’t tell us about all the challenges they face, and there are certain things that we simply cannot ask from the relative comfort of Washington, DC.

The press has done an excellent job of documenting the economic and political costs of Covid-19 across Latin America, including how authoritarian governments have used the pandemic as an excuse to further crowd out other voices and challenges to their power. But the quality of life has gotten worse in place like Venezuela, too. Stay-at-home orders are difficult enough in countries where people enjoy fast internet, a free press and good public health services, but circumstances are especially dreary in countries with crumbling infrastructure, media restrictions and a predatory government.

John Polga-Hecimovich is an Assistant Professor of Political Science at the U.S. Naval Academy. The views expressed in this article are solely those of the author and do not represent the views of or endorsement by the Naval Academy, the Department of the Navy, the Department of Defense, or the U.S. government. U.S. Naval Academy. Contact: polgahec@usna.edu

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...