About the Author

Nathalie Gazzaneo is a second-year Master in Public Policy student at the Harvard Kennedy School.

The Rock Salt of the Earth

No Price for Sorrow

In Maceió, my hometown in Brazil, adding to the Covid-19 crisis, my community has been concerned about how to handle the crisis generated by the rock salt extractive business that so far has displaced over 8,000 families from high-risk areas in four districts of the city.

Rock salt extracted from the underground was for decades at the core of the economic value chain of the State of Alagoas and its capital city Maceió. Since 2002, Braskem S.A. had used the rock salt extracted from more than 30 wells over the territory of Maceió to feed a large petrochemical industrial complex in the region. On the surface, none of that seemed much like a Greek tragedy, at least until recently.

Since 2018, the districts of Bebedouro, Bom Parto, Mutange, and Pinheiro in Maceió have been literally collapsing under their residents’ feet. They were hit by a seism measuring about 2.5 on the Richter Scale. Roadways collapsed and exposed huge craters. Several houses’ walls cracked and floors started sinking. In mid-2019, public authorities concluded in an official study that the destabilization of underground empty cavities from decades of rock-salt mining in Maceió had for the most part set off the collapse.

Thanks to the coordinated action of affected communities and the pressure from lawsuits, Braskem has suspended all its rock salt extraction activities in Alagoas. The company was also pushed to roll out a multi-million Brazilian Reais program to compensate and relocate the over 8,000 families living in the highest risk areas of the districts of Bebedouro, Bom Parto, Mutange and Pinheiro.

As a child, when my father drove us home from school, I daily peeked at the cobogó bricks in the staircase and windows of the district of the Bom Parto church and crossed the deactivated railways that cut the districts of Mutange and Bebedouro. I also spent a good part of my childhood years in a dance studio in the heart of the district of Pinheiro.

In January 2021, when I was last in my hometown, I was appalled to witness how districts deeply entrenched in Maceió’s culture and history and home to so many families and their dreams were turned into complete ghost areas.

Bebedouro, Bom Parto, Mutange and Pinheiro are not just the scenery of fleeting memories from my childhood, nor just names bordering the Mundaú Lagoon in the map of my hometown. They used to be home to more than 50,000 people and a living repository of part of the city’s shared history, identity and dreams – all of which collapsed with the land under the residents’ feet. How can we even begin to reckon with such a huge collective human tragedy?

The rock salt disaster in Maceió is one among a nefarious series of mass disasters resulting from the greed of mineral extrativist business in Brazil’s recent history. In Maceió and Mariana and Brumadinho before it, the hard-fought for relocations of families to safer areas and fair monetary compensation are barely an effective response to the people whose lives and dreams sunk and cracked as much as their houses.

Such losses are not entirely compensated by money and are not susceptible to real healing even through individual psychological support alone. This is attested to by the outbreak of diseases of despair among surviving victims of the 2018 Brumadinho dam collapse, even among those who received psychological assistance.

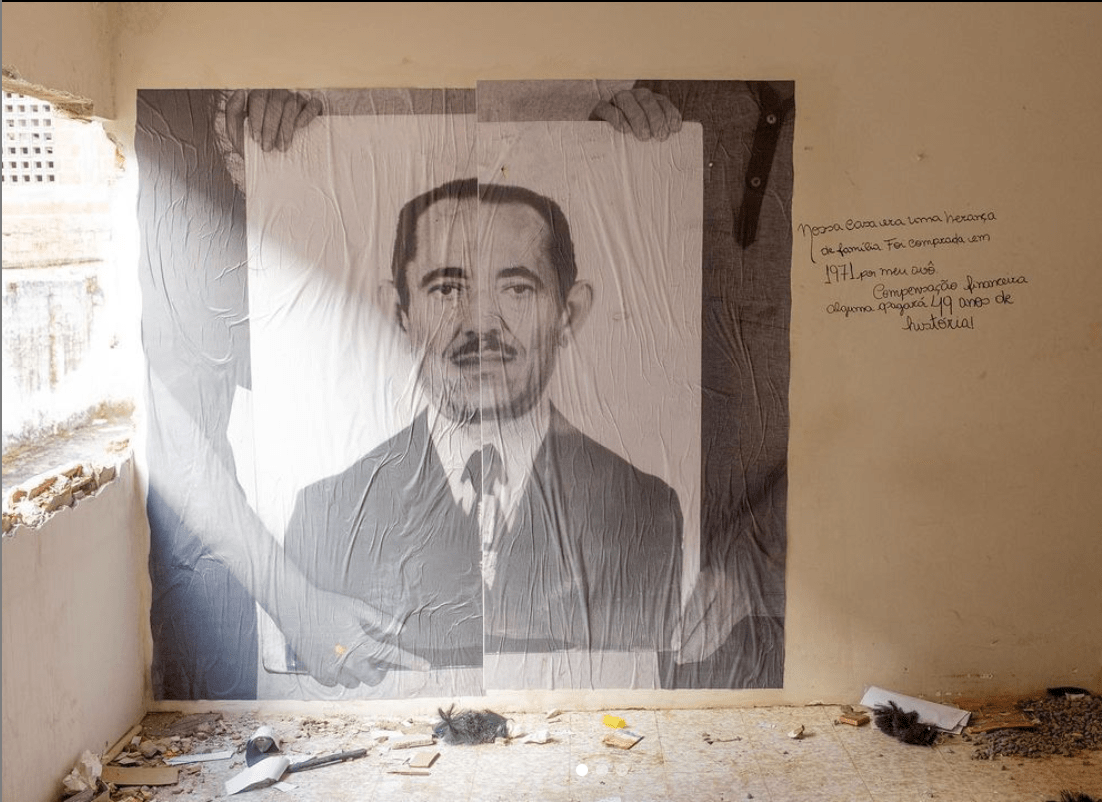

“No financial compensation can erase 49 years of history,” reads a handwritten note on the walls of an already evacuated house that received the artistic intervention of the project @agentefoifelizaqui (we were happy here) in the district of Pinheiro.

The question motivating the artists behind @agentefoifelizaqui – “What’s the price of 40,000 lives?” – asks for a serious embrace of the life stories of those touched by the tragedy. The way the project combines art with the power of listening, telling and honoring the stories of families who had their lives torn also reveals a deeply humanized, and too often neglected, avenue for effective healing on a collective level.

We need more such avenues to respond to mass disasters, like the one in my hometown.

Mobilizing writers and poets to register those families’ memories and ensure they are not forgotten. Inviting film directors to expose the surreal reality, close to a shoddy sci-fi plot, of the local power dynamics that every now and then result in a tragedy like this one. We should be taking seriously ideas like gathering relocated residents in a choir or orchestra, or transforming the ghost districts in a massive garden, planted and cared for by many hands from this and next generations.

All of this may sound too naïve, a fantasy from a fellow Maceioense who left the city over a decade ago and has no touch with the daily hurdles of the fight for relocation and compensation. As a lawyer and public policy graduate student, I respond that while the collective reckoning with the sorrow of the victims is absolutely not a substitute for the more practical and obvious actions that are already under way, it is a much welcome complement, and one on which the long-term efficacy of the former relies.

As a citizen and humanist, I believe that such reckoning is not something from another world. It’s what gives meaning to life. It’s what gives communities affected by massive trauma—and all of us—the collective wit and spirit to reweave hope and become the salt of the earth.

More Student Views

Oppression Disguised as Aid: The Colonial Legacy Behind Haiti’s Struggling Healthcare System

In rural communities in the United States, it takes an average of 34 minutes to reach the nearest hospital. In rural Haiti, the average is two hours. Infectious diseases including tuberculosis, cholera and HIV/AIDS go untreated due to the lack of basic healthcare infrastructure and the violence disrupting the provision of health services.

“Yoltajtol. A Word from the Heart”: The Nahuatl Worldview Comes to Harvard

On February 28th, the Moses Mesoamerican Archive and Research Project held the inaugural Nahuatl Workshop “Yoltajtol, A Word from the Heart.” The workshop had the twofold goal of offering an introduction to the Nahuatl language and showing to the participants that Nahuatl is a constitutive part of present-day indigenous peoples’ worldview.

CPR Ambassador Journey

English + Español

One of the simplest yet most effective ways of saving a life in the case of sudden cardiac arrest is cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). It’s an accessible procedure to be trained on, as almost anyone of any age can learn it. Knowing this, and that performing CPR right after cardiac arrest increases survival chances two to three times, why hasn’t everyone been trained on CPR at some point in their lives? (American Heart Association).