The Three Lives of Fernando Solanas

FIRST LIFE: THE CLANDESTINE FIGHTER

In 1969, Fernando Ezequiel Solanas (b. Buenos Aires, 1936), in collaboration with other Argentine filmmakers, filmed a chapter of Argentina, mayo de 1969: los caminos de la liberación. The film has never been restored in its entirety, and few have seen it. Nevertheless, it remains a legendary testimony to collective political unrest, particularly influential for its promotion of cinema as a new vehicle of protest against a ruling regime.

Solanas’ filmic inspirations were not exclusively cinematic: his earlier studies in literature, music, dance and law led him to pursue theater arts at the Conservatory of Dramatic Arts (Conservatorio de Arte Dramático), where cinema would eventually seduce him. His career in cinema began at age 26, with the filming of Seguir andando (1962). Another short film, Reflexión ciudadana (1963), followed a year later.

Like his friend Octavio Getino, Solanas was a Peronist, and in 1968 the two men directed the most influential political documentary of the era: La hora de los hornos: Notas y testimonios sobre el neocolonialismo, la violencia y la liberación. Divided into three parts, the 255-minute documentary managed to be many things at once: instrument of leftist political and social protest; manifesto; educational cinematic debate; essay of cultural interpretation of Latin America in general and of Argentina in particular; a filmic collage, collecting and juxtaposing fragments from other films of the period; active artifact in the democratization of images; unofficial history. It was also the most controversial film of the 1960s.

Solanas and Getino also founded the Grupo Cine Liberación and developed the theory of “Third Cinema”: a cinema that is neither commercial nor authorial, emerging instead from the public at large. Meanwhile, the two kept in close contact with Juan Domingo Perón during his exile in Madrid (1955-1974), following his removal from power in the so-called Liberating Revolution (Revolución Libertadora). The relationship resulted in their 1971 film, Perón: Actualización política y doctrinaria para la toma del poder.

Solanas’ second full-length film, Los hijos de Fierro (1972), appropriated a well-known literary character in order to experiment with combining scenes of fiction and documentary. This innovation achieves an extremely personal reading ofMartín Fierro, the classic “gauchesco” poem of 1872. Adding to the film’s unique ambition, much of the dialogue is written in the same octosyllabic meter as José Hernández’s poem. Given the poem’s fundamental role in Argentine culture, it becomes a poignant frame of reference and brilliant backdrop for a complex film that oscillates between epic and lyric, realist and mythic, allowing the poem’s “characters” and scenarios to articulate a political allegory of the 1970s in Argentina.

In 1975, the military executed another coup d’etat in Argentina. The following year, Solanas went into exile.

SECOND LIFE: EXILE AND NOSTALGIA

In France, and later upon his return to Argentina, Solanas’ work underwent substantial changes. Without losing his political mission, the filmmaker started to develop fictional stories, mixing present realities with the political and cultural myths of Argentina, as he had begun to do with Los hijos de Fierro.

Music, mise-en-scene, and concern with the plastic and the visual assumed primacy in his work. This new combination of elements produced a masterpiece of intense emotional force: Tangos, el exilio de Gardel (1985).

Tangos is the great film of South American exile. It was filmed in France, paying tribute to the significance of that country in Argentine cultural roots, to France’s pivotal role in the historical acceptance of the tango (given its origin as a music and dance of brothels), to the supposed birth of Carlos Gardel in Toulouse, and alluding to the two and a half decades of exile the caudillo San Martín spent in Boulogne-Sur-Mer. Paris provides the “natural” scenery for Tangos, such as the handsome “Cortázarian” bridges where the pairs of dancers choreograph their dances. Solanas avoids touristy and cliché Parisian scenes, favoring the dense and rich presence of the city, its streets, and its old buildings, a presence that bestows a certain charm on the lives of the exiled protagonists and corresponds with the musical, literary, visual, and filmic culture of these years of “mythic” reality of Argentina for one who lived abroad, in exile.

In Tangos, Solanas directs a film that is both personal and representative of the era. This aesthetic is risky, but at the same time participates in a musical tradition that is well established both inside and outside the cinema. The splendid choreography displays a variety of tango styles, from traditional to modern, allowing the dance to shine. The progression also shows that the narration, too, is mobile, and should not remain paralyzed in a simple realist telling.

When democracy was restored in Argentina in 1983, Solanas returned.

After Tangos, Solanas portrayed the other side of exile: “in-sile.” Situated in Buenos Aires, his film Sur resumes the theme of the mythology of tango with the same talent and creativity on display in Tangos. Divided into four sections (“La mesa de los sueños,” “La búsqueda,” “Amor y nada más,” and “Morir cansa”), the film expresses the author’s willingness not only to be attentive to the direct experience of his characters, but also to turn to metaphor, myth, and poetry. The sets and cinematography achieve a ghostly atmosphere, with lights curiously multiplied by mist, smoke, and rain-wet ground. Sur does not employ the choreography of Tangos, but the two films share the aesthetic required to tell a subjective story in an objective manner. Sur is the story of love for a woman, for a city, and for a country.

Democracy is supposed to permit and promote political and cultural criticism. In the years following his return to newly democratic Argentina, Solanas produced a variety of films and articles which criticized successive Argentine governments, especially that of Carlos Saúl Menem, president of Argentina from 1973-76 and 1983-89. Although Menem was also a Peronist, he ended up destroying the Peronist movement, “selling” the country by privatizing the state’s resources and signing agreements of pardon and amnesty for the militants of the Dirty War.

El viaje (1992) and La nube (1998) satirized the government, and not without consequence. Though one might expect the personal safety of citizens to be more secure in a democracy than under a dictatorship, Solanas’ criticisms were met with violence: as he left a studio on May 21,, 1991 unknown gunmen made an attempt on his life.

THIRD LIFE: THE STREETS ONCE AGAIN

Argentina, 2001. Economic, social and labor conditions became insufferable under the administration of De la Rúa. In Buenos Aires, people took to the streets in massive and irrepressible protests. The president declared a state of siege, which only aggravated the situation. The more police that were sent to the street to repress the uprising, the more hopeless the battle for control became. The expression “¡Que se vayan todos!” (“Out with them all!”) signaled a collective will that was difficult to stop or contain. On December 21, De la Rúa resigned ignominiously, fleeing the Casa de Gobierno in a helicopter.

These events energized Solanas, as they did thousands of other Argentines. He was inspired to capture on film a historical milestone that, while it had plenty of antecedents, would have far-reaching consequences. Solanas felt that current events should be explored in order to understand the historical moment, as well as the ones that would follow. Above all, he wanted to put in perspective a long history of governmental corruption, on the one hand, and the history of popular resistance on the other.

Three decades had passed since La hora de los hornos, when Solanas rediscovered the cinema of the street. Cinematographic techniques had changed in these years, and heavy 16mm cameras were traded in for camcorders and high-definition digital. With these innovations, the cinema of Solanas regained its youth. The filmmaker hit the pavement to record the events that shook the country, directing four notable documentaries in just five years: Memoria del saqueo (2004), La dignidad de los nadies (2005), Argentina latente (2007) and La próxima estación (2008).

With youthful energy, Solanas returned to a cinema of activism and exposé, but this time with four decades of cinematographic experience, allowing him to assume a resounding and authoritative first-person account. Indeed, Solanas narrates each of these films himself, speaking on camera with his protagonists. Memoria del saqueo, as its title implies, is the “story” of how Argentina was looted by politicians who privatized public services (airlines, telephones, and others), and of the misdeeds surrounding the financial and economic disaster and popular revolt of 2001.

La dignidad de los nadies gave voice to these “anonymous” people that fomented the uprising of 2001, as well as those that have agitated against the continual abuses in Argentina. Inverting the perspective of Memoria del saqueo, which relates the abuses of the system, La dignidad de los nadies tells the story of popular resistance.

The trend continues in Argentina latente and La próxima estación. This last film undertakes a sharp illustration of the looting with just a single example: the state railroads. In some sections of the film the thefts described are nearly unbelievable: looters make off with not only thousands of steel rails, but also with the warehouses that stored them. As in all of his films, Solanas points directly to the names of the accused. In this sense his films are also escraches, a colloquial and untranslatable word that describes physical acts of denunciation, peaceful but effective actions of the victims themselves, that is, the citizens. Accompanying these acts is the cinema, the means of communication most feared by the System.

Las tres vidas de Fernando Solanas

Por Jorge Ruffinelli

PRIMERA VIDA: GUERRERO CLANDESTINO

En 1969, Fernando Ezequiel Solanas (Buenos Aires, 1936), filmó, junto con otros cineastas argentinos, un capítulo de Argentina mayo de 1969: los caminos de la liberación, una película legendaria que hasta hoy no ha podido restaurarse entera y que pocas personas han visto. Era un testimonio de la inquietud política colectiva que encontraba en el cine un vehículo de protesta contra el régimen imperante.

Los antecedentes de Solanas no se ubicaban exclusivamente en el campo del cine. Había comenzado a formarse en literatura, música y abogacía antes de ingresar en el Conservatorio de Arte Dramático para estudiar teatro, cuando el cine comenzó a seducirlo. A los 26 años hizo Seguir andando (1962) y al año siguiente Reflexión ciudadana (1963), dos cortometrajes.

Solanas era peronista, igual que su amigo Octavio Getino, y en 1968 ambos realizaron el documental político más importante e influyente de la época: La hora de los hornos: Notas y testimonios sobre el neocolonialismo, la violencia y la liberación. Este documental dividido en tres partes y con una duración total de 255 minutos se propuso y consiguió ser muchas cosas a la vez: instrumento de denuncia política y social desde un enfoque de izquierda; ensayo de interpretación cultural de América Latina y ante todo de Argentina; collage colectivo (en la medida en que recoge fragmentos de otros films de la época); manifiesto y panfleto; cine educativo y de debate; artefacto activo de democratización de las imágenes; historia no oficial. Fue también la película más controvertida de los 60s.

Solanas y Getino eran “peronistas”; fundaron el Grupo Cine Liberación y desarrollaron la teoría del “Tercer Cine”: un cine que no era ni comercial ni “de autor” sino que debía surgir del pueblo mismo. Mientras tanto, Juan Domingo Peron vivía entonces en su exilio madrileño (1955-1974) desde que la llamada Revolución Libertadora militar lo quitara del poder en 1955, mediante un golpe de estado. Mantuvieron contactos cercanos con Perón y en 1971 filmaron Perón: Actualización política y doctrinaria para la toma del poder.

Solanas utilizó a un personaje literario para realizar su segundo largometraje —Los hijos de Fierro (1972)—, en el que experimentó exitosamente combinar escenas de ficción con documental. Los hijos de Fierro es una lectura personalísima que el director/guionista realizó del célebre poema “gauchesco” de 1872, Martín Fierro, llegando incluso a escribir buena parte del film con la misma métrica octosilábica de José Hernández. Dado que el poema forma parte fundamental de la cultura argentina, le resultó un magnífico telón de fondo y un marco de referencia sobre el cual construir una estructura compleja entre épica y lírica, realista y mítica, haciendo de los “personajes” y situaciones originales la fuente de una alegoría política sobre los años sesenta.

En 1975 los militares dieron un nuevo golpe de estado en Argentina. En 1976, Solanas emprendió el camino del exilio.

SEGUNDA VIDA: EXILIO Y NOSTALGIA

La obra de Solanas en Francia y, más tarde, a su regreso a Argentina, sufrió un cambio sustancial. Sin perder la carga política, desarrolló historias de ficción, y mezcló el presente con los mitos culturales y políticos argentinos, como había comenzado a hacerlo en Los hijos de Fierro.

La música, la puesta en escena y la preocupación plástica y visual adquirieron primacía, y esa nueva combinación de elementos produjo una obra maestra, de intensa fuerza emocional: Tangos, el exilio de Gardel (1985).

Tangos es la gran película del exilio sudamericano. Fue filmada en Francia, entre otras cosas, por la significación que ha tenido el país europeo en las raíces culturales argentinas; por la importancia de Francia en la aceptación histórica del “tango” (dado su origen como danza y música prostibularios); por el supuesto nacimiento de Carlos Gardel en Toulouse, y por las dos décadas y media que el caudillo y prócer San Martín vivió su propio exilio en Boulogne-Sur-Mer. Lo que aportó París fue la escenografía “natural”, los hermosos puentes “cortazarianos” sobre y debajo de los cuales las parejas coreografían sus danzas. Solanas evitó el París turístico o típico, pero la presencia densa y rica de la ciudad, de sus calles, de sus edificios viejos le da a la vida de sus personajes exiliados el encanto que se corresponde con la cultura musical, literaria, plástica y, por qué no, tambiénfílmica, vivida desde Argentina durante tantos años como realidad y como mito.

En Tangos Solanas hizo una película personal y a la vez representativa de una época y una circunstancia colectiva, con una estética de riesgo y al mismo tiempo contando con una tradición musical dentro y fuera del cine. La espléndida coreografía hace brillar al tango como baile, lo representa en sus diversos estilos de danza (desde lo tradicional a lo moderno), y demuestra que la narración no puede quedar anquilosada en un simple contar realista.

Cuando se restituyó la demoracia en Argentina, Solanas regresó al país. Era 1983.

Después de Tangos —la película del exilio—Solanas logró completar la otra cara del exilio —el in-silio— y lo hizo con Sur, ambientada en Buenos Aires y retomando la mitología del tango con el talento y la creatividad demostrados en Tangos. Dividido en cuatro capítulos (“La mesa de los sueños”, “La búsqueda”, “Amor y nada más” y “Morir cansa”), el film expresa la voluntad del autor por no atenerse sólo a la experiencia directa de sus personajes, sino volar hacia la metáfora, el mito y la poesía. Los decorados y la fotografía logran una atmósfera fantasmal, con luces curiosamente multiplicadas por el suelo mojado por la lluvia, con neblinas y humaredas. No hay en Sur la coreografía de Tangos, pero sí el esteticismo necesario con que contar una historia tan subjetiva como objetiva. Es una historia de amor por una mujer, por una ciudad, por un país.

Se supone que la democracia permite y promueve el uso de la crítica. En los años siguientes, y con películas y artículos periodísticos, Solanas emprendió la crítica de los gobiernos argentinos, y ante todo, de Carlos Saúl Menen como presidente de Argentina (1973-76; 1983-89). Aunque él mismo peronista, Menem acabó por destruir al movimiento peronista, “vendió” al país al privatizar de los recursos del estado, y firmó decretos de aministía y perdón para los militares de la “guerra sucia”.

El viaje (1992) y La nube (1998) fueron filmes muy satíricos con respecto al gobierno. La seguridad de los ciudadanos suele ser mayor en democracia que en dictadura; sin embargo, Solanas sufrió un atentado contra su vida cuando a la salida de un estudio fue baleado por desconocidos el 21 de mayo de 1991.

TERCERA VIDA: LAS CALLES OTRA VEZ

Argentina, 2001. La situación económica, social y laboral se hizo crecientemente insostenible en la Argentina de De la Rúa. En Buenos Aires la gente se volcó a la calle de manera masiva e irreprimible. El presidente declaró el estado de sitio, y sólo aumentó la insatisfacción popular. Por más policías que se enviaran a las calles para reprimir y frenar la “pueblada”, la batalla estaba perdida. La expresión “¡Que se vayan todos!” señaló una voluntad colectiva difícil de detener y debilitar. El 21 de diciembre De la Rúa renunció ignominiosamente, y en un helicóptero huyó de la Casa de Gobierno.

Estos hechos entusiasmaron a Solanas, así como a cientos de miles de otros argentinos, y lo inspiraron para registrar en cine una historia viva que alcanzaba un hito, tenía amplios antecedentes y tampoco acabaría allí. Solanas sintió que ese proceso debía ser explicado, como una manera —la mejor a su alcance— de entender los fenómenos que se vivían, otros que surgirían necesariamente a partir de ese punto, y, ante todo, de poner en perspectiva una larga historia de corrupción gubernamental, por un lado, y de resistencia popular por otro.

Habían pasado tres décadas desde La hora de los hornos cuando Solanas descubrió otra vez la calle. Las tecnologías del cine habían cambiado en esas décadas, y de las pesadas cámaras de 16 milímetros podía pasarse al camcorder y al cine digital de alta definición. Con estas opciones, el cine de Solanas fue joven otra vez. El cineasta salió al camino al registrar los sucesos que conmovían al país, y realizó en sólo cinco años cuatro documentales notables: Memoria del saqueo (2004), La dignidad de los nadies (2005), Argentina latente (2007) y La última estación (2008).

Con ellos, Solanas volvió a capturar el ánimo juvenil del cine de denuncia, pero ahora contaba con más de cuatro décadas de experiencia cinematográfica, y podía asumir su relato sonoro y visual con toda la propiedad de la primera persona. En efecto, es Solanas quien narra cada una de estas películas y quien dialoga, en cámara, con los protagonistas. Memoria del saqueo es, como lo implica su título, una “historia” de cómo Argentina fue saqueada por los poderes políticos mediante la privatización de sus servicios (líneas aéreas, teléfonos y demás), hasta el desastre financiero y económico y la revuelta popular de 2001.

La dignidad de los nadies entregó la palabra a los seres “anónimos” que protagonizaron tanto el levantamiento de 2001 como la resistencia permanente ante los abusos del sistema. Es la contracara de Memoria del saqueo: éste es la historia del sistema, y La dignidad de los nadies es la historia de la resistencia popular.

Esto se continúa en Argentina latente y en La última estación. Esta última es la ilustración del saqueo en un solo pero amplio ejemplo: los ferrocarriles del estado. En algunos capítulos hasta el robo parece increíble: no sólo miles de rieles de acero fueron robados a pleno sol, sino también los grandes galpones en que se conservaban. Como en todas sus películas, el índice acusador de Solanas toca a personas con nombre y apellido. Sus películas, además de estar admirablemente filmadas, son escraches, palabra de uso popular y probablemente intraducible, que describe acciones físicas de denuncia, pacíficas y efectivas, de las víctimas mismas, es decir, de los ciudadanos. Y el cine los acompaña como el medio de comunicación más temido por el sistema.

Fall 2009, Volume VIII, Number 3

Jorge Ruffinelli, editor of Nuevo Texto Crítico, is a professor in the Department of Spanish and Portuguese at Stanford University and a recognized authority on Onetti, García Márquez, Juan Rulfo, and Latin American literary history. His critical work has recently focused on Latin American cinema.

This article was translated from the Spanish by Adam Morris.

Jorge Ruffinelli, editor de Nuevo Texto Crítico, es profesor en el Departamento de Español y Portugués de la Universidad de Stanford y una autoridad reconocida en Onetti, García Márquez, Juan Rulfo e historia literaria latinoamericana. Su labor crítica se ha centrado recientemente en el cine latinoamericano.

Related Articles

Coconut Milk in Coca Cola Bottles

Common knowledge has it that virtually any movie, once removed from its original cultural context of production and reception, might be either misunderstood and misperceived or re-interpreted and re-signified. Likewise, we may agree that national cinemas seek to define, challenge….

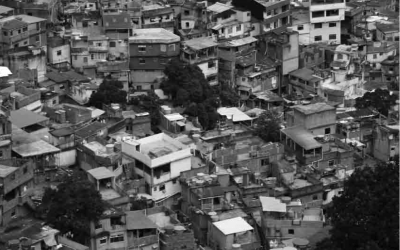

Neither the Sertão or the Favela

To frame the poetics of the ordinary in terms of subtlety and delicateness is to propose an antidote both for cynicism and for what I call Neo-Naturalism. Its appearance, at least in Brazilian cinema and literature, has been clearly identified, ranging from peripheral subjects…

Brazilian Cinema Now

Snow falling in the city of São Paulo, in southern Brazil? Taking a helicopter in São Paulo then arriving a few moments later in the deep wilderness of the Amazon jungle, half a continent further away to the north? Then meeting a white Asian tiger in the heart of the Amazon forest?…