The Vaccine Revolt in Brazil

I have long been fascinated by history. As I sit quarantined in my apartment in Vancouver, Canada, far from my native Brazil, I cannot help but ponder the differences in how epidemics have affected my homeland.

Epidemics tend to increase economic inequalities. From the beginning of the 20th century to the present, the world has faced five pandemics, including the 1918 Spanish flu, the 1957 Asian influenza, the 1968 Hong Kong flu, the 2009 H1N1, and now Covid-19. Brazil, between 1904 and 1908, faced a smallpox epidemic in addition to high rates of cases of bubonic plague and yellow fever.

At the beginning of the 1900s, Brazil was transitioning from an economy based on slave labor to wage labor but with an incipient labor force. The Brazilian population in 1904 was around 17 million inhabitants, with approximately two million immigrants from Europe and Japan. The Brazilian economy was 21% in the industrial sector and 79% in the agricultural industry. The textile industry manufactures of drinks, shoes, and oils for food. In 1904, Oswaldo Cruz, the Director of Public Health, proposed a clean code that instituted the disinfection of factories and residences, demolition of buildings considered harmful to public health, and control of yellow fever cases, smallpox and bubonic plague. He also created the Sanitary Police.

However, Cruz adopted a repressive style against Brazilians who were wary of the emergence of the General Directorate of Public Health, which mandated that everyone had to be vaccinated. Between January 10 and 13, 1904, five days after the mandatory vaccination, 495 people were arrested, 461 deported, 110 wounded, and 30 killed in a battle in the streets of Rio de Janeiro against government troops involving more than 2,000 people. The conflict was named the Vaccine Revolt.

What were the causes of the Vaccine Revolt and why did the smallpox epidemic and bubonic plague affect the most impoverished population? The first cause of the revolt was the violence used by the government to vaccinate the population. Armed soldiers invaded the houses in the poorest areas of the city, and all of people’s belongings were taken to a warehouse or burned. The majority of the people did not even know what a vaccine was, which caused a massive fear in the population. Another cause was the colossal dissatisfaction of the community with the government’s public services such as garbage collection, unhealthy housing, the absence of a water and sewage system that only served the affluent areas of the city, and the terrible public transport with ancient trams that broke down often.

The conflict forced President Rodrigues Alves (who would die of the Spanish flu in 1919) to suspend mandatory vaccination. His government’s actions were considered a disaster. One of the government’s disastrous measures was to pay people who were willing to hunt mice and hand them over to health inspectors. This measure promoted real chaos in the city and made it appear created breeders of rats to obtain an income from hunting rodents.

Even with the polarized political environment, Oswaldo Cruz motivated President Rodrigues Alves to send Congress a bill to reinstate the mandatory vaccination throughout the natural territory. Only individuals who prove they are vaccinated would get employment contracts, school enrollment, marriage certificates, and travel authorization, the bill proposed.

It made vaccination and booster vaccination against smallpox mandatory throughout the Republic. The new Mandatory Vaccination Bill 1201 of October 31, 1904 mandated smallpox vaccination for infants under sixth months old, followed by booster vaccinations at seven years old and every seven years thereafter. All children and adults, including Army officers and soldiers, must be vaccinated if they cannot prove they have been vaccinated within the past six years. The Ministry of Justice and Interior Affairs, through the General Directorate of Human Health, were put in charge of implementation.

With the end of slavery in 1888, jobless ex-slaves with nowhere to go began to inhabit old mansions abandoned around the train terminal-Central Railway of Brazil. The living conditions in these places were very unhealthy, facilitating the emergence of many diseases. In 1893, then-Mayor Barata Ribeiro ordered the overthrow of many of these so-called Pig Heads, forcing these residents to move to the area between the Central Railway of Brazil, the British Cemetery and the Port region. Then comes the first slum in Rio de Janeiro known as Morro da Providencia or Morro da Favela. It received this name favela because of the abundant presence on an herb known as “faveleira”. In 1904, because of the Vaccine Revolt, the government tried unsuccessfully to remove Morro of Providencia. Many of these residents fought against government troops during the Vaccine Revolt because of the sanitary measures adopted by Oswaldo Cruz.

The Vaccine Revolt revealed a Rio de Janeiro marked by enormous economic and political inequality, where even the geography of the city helped to increase the problem. Despite being the largest city in Brazil at the beginning of the 20th century, Rio de Janeiro maintained the urban aspect of a colonial town, which hindered the city’s modernization, especially the central region. The wealthiest section of the population moved towards the south side of the town like the Botafogo neighborhood, leaving behind areas around the city center and the São Cristovão neighborhood where the Royal Family had resided until the Proclamation in 1889. Rio de Janeiro’s south zone already had an adequate housing infrastructure and access to treated water—essential to prevent diseases, good garbage collection and good public transport. In addition, real estate moguls began to invest heavily in the south side. New tram lines and two tunnels were built connecting the Botafogo and Copacabana neighborhoods, the latter transforming from a place inhabited by fishermen to one where the wealthiest families in the city resided.

In 1900, political leaders and civil society members were very optimistic about the country’s future. Santos Dumont, a Brazilian inventor, made his first flight with the 14Bis in Paris. Artists and intellectuals demonstrated through art, and manifestos trying to insert Brazil in the international context. The culmination of that period was the 1922 Modern Art Week.

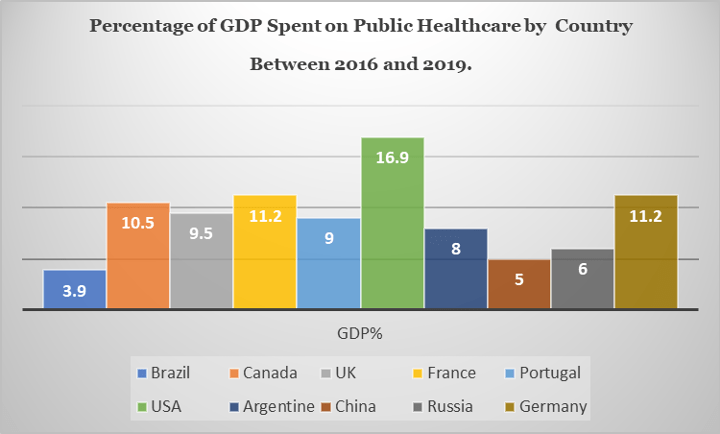

Epidemics reveal the chronic problems of any society and, in countries like Brazil, social issues not solved in the past are looming in the present. Investments in public health in Brazil represented 3.9% of GDP in 2019. Comparatively, Canada, the United States and Germany respectively invested 10.5%, 16.9% and 11.2% of GDP in 2018.

Extreme poverty in Brazil rose by approximately 11% between 2018 and 2020 (May). The crisis had already affected the poorest, but nothing was done. Readjusting the Bolsa Família program that serves the most impoverished population by approximately 20% will spend only 0.1% of GDP. Brazil needs to bring together experts in science and inequality. Social inequality makes the consequences of a Pandemic or Epidemic much worse. The Brazil of the Vaccine Revolt realized this with hard blows. Pandemic in Brazil became a political issue, and that was not a good thing. There are economic indicators that prove that social policies favor the poorest; the result will be much better in the economy.

The Brazilian government and its supporters try to naturalize the tragedy of Covid-19 in a kind of collective paranoia. Brazil needs to carefully evaluate the events surrounding the Vaccine Revolt. There is meaningful learning from past epidemics, especially the Vaccine Revolt. As Oswaldo Cruz did, the country needs to strengthen science through research institutes and universities to produce knowledge and consequently understand the behavior of diseases that affect a society.

As I write this short article, Brazil has already exceeded 120,000 dead, and Government officials argue that the coronavirus is democratic, affects everyone regardless of class or ethnicity, but when we assess the causes of the Vaccine Revolt, we will soon know that this is not true. It affects the most marginalized portion of the population in more significant numbers, like the smallpox epidemic in 1904.

Here in quiet Vancouver, I do not pretend to teach Brazilian government officials the importance of looking at the role of science and scientists in the rearview mirror. We Brazilians have historical difficulties in dealing with our past. We are always trying to look forward. Oswaldo Cruz and his struggle during the Vaccine Revolt cannot become just a figure from the past. The legacy of combating Covid-19’s pandemic in Brazil is under threat from religious fanaticism and exacerbated political division. The retrograde anti-scientific movement is not only present in Latin America, but in Brazil, it is serving as ammunition for the increase in the hourly irreconcilable political division between the extreme right and sectors of the left.

Strengthening the Unified Health System (SUS) and investing in a social reform agenda is necessary to construct a less unequal society and guarantee the population’s access to various means to protect its health.

This is an excellent opportunity to prove to ourselves that we are not a nation of hedonists and accept our potential condition on a planet affected by a pandemic where actions of solidarity, self-organization, and collective care can help in the struggle for life. We can learn from the past.

Giovane Batista Assuncao worked as a researcher and university professor in Brazil for many years. He is now a language and high school teacher in Vancouver, Canada.

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...