Todas las flores

The Eternal Blooming of Colombia’s Trans Spring

The long line could be seen even before arriving at the movie theatre. Dozens of impatient people crowded at the box office to see if tickets were still available. The mood was festive. People of different generations and walks of life greeted each other with hugs; long-time acquaintances met again; loud laughter was heard, along with the sound of high heels scurrying to find a seat. It was a day to celebrate, and not just because it was June 28, the International Day of LGBTQ+ pride, but also because after filming for 17 years, Todas las flores (All the Flowers), a 2023 documentary about the lives of trans sex workers in the Santafé neighborhood of Bogotá, Colombia, finally had its premiere.

Directed by the Puerto Rican filmmaker Carmen Oquendo-Villar (a 2018-19 DRCLAS Visiting Scholar), and produced by her, Alejandro Ángel (Armadillo: New Media & Films, Colombia) and Annabelle Mullen-Pacheco (Belle Films, Puerto Rico and España), Todas las flores offers an intimate look at the community that revolves around Tabaco y Ron (Tobacco and Rim), a multi-purpose space that has welcomed generations of trans women, who have found a safe space to socialize, work and live there. As Diana Navarro Sanjuan, one of the most important trans leaders who died in 2022 and to whom the film is dedicated, observed, “Tabaco y Ron has always been an emblematic site for us transgender women who engage in prostitution because it was the first whiskey bar […] , the first site open to the public that gave us the opportunity to engage in prostitution in an establishment open to transgender women. They even offered us housing […] and because of this some call Guillermo “Mother Guillermo,” because Guillermo is like a mother to us, especially those of us, the old-timers, who came here in the 80s.” Todas las flores is thus a choral, multi-faceted portrait over a period of time of those who in one way or another have made this space their home.

But it wasn’t always like this. Originally, the film focused on Diana Navarro. However, bit by bit Oquendo-Villar came to the conclusión that, rather than an individual portrait, the documentary should be a collective history made up of many voices over several years. Thus Todas las flores was born. This does not mean that Oquendo-Villar had abandoned the idea of a full-length film on Navarro Sanjuan’s life and work. Although Diana is no longer here to see it, that project continues and now is in the phase of post-production.

A special merit of Todas las flores is that it avoids looking at the women from an exotic, fetishistic or ethnographic perspective that is so common when cis (no trans) people develop narratives about trans people. Thanks to the close ties Oquendo-Villar developed with the people and communities who participated in the project over the many years of filming, especially with Diana Navarro, the documentary inhabits the space of daily life, showing us, without idealizing or sensationalizing, the day-to-day life of those who live and work in Tabaco y Ron.

Another unusual element of Todas las flores is that it presents an inter-generational look at the barrio and the trans communities that have made their home there. In a community where life expectancy in Latin America is 35 years, the rescue and preservation of the experience and testimonies of trans mothers is a valuable contribution to historical memory that resists the multiple forms of silencing these trans women and making them invisible, particularly if they face other barriers such as social class, race, HIV-status and prostitution.

This diachronic view permits us to understand what has changed, although the trans community still faces different types of violence in Colombia. In this sense, it’s useful to remember the framework developed by the Collective Virus Epistomology to analyze violence and the sexism of non-trans individuals against trans people. As I explain together with my colleagues Helena Suárez Rodríguez and Franklin Gil Hernández in the introduction to our volumen dedicated to trans studies in the Revista de estudios colombianos (No. 58, 2021), the Colective proposes three categories: multi-conflict, movements and permanent migration, and the self-fulfilling prophecies, urban and structural segregation.

The term “multi-conflict” explains that, beyond direct violence, “everything is a conflict for trans people because […] all the lived experiences of the trans community are marked by a conflicto: going to the doctor, going out on the street, enjoying spaces shared by others, going to the supermarket, among others.” (Colective Virus Epistemológico, 2020, pág. 81. In Martínez, Juliana; Suárez Rodríguez, Helena y Gil Hernández, Franklin. Revista de estudios colombianos. No. 58, July–December, 2021, p. 6). In talking about movements and permanent migrations, the expulsion or uprooting of families, communities is a common experience for many trans persons who, moreover, tend to repeat the experience for reasons ranging from the continual search for a means of livelihood to the aggresive persecution by state forces, paramilitary groups and other violent actors. Finally, self-prophecies, urban and structural segregation, refers to the fact that trans people are all to often relegated to the sectors of the city with high rates of poverty, unemployment and violence, since the mere presence of trans people is criminalized and persecuted in other zones.

Through its multiplicity of histories, Todas las flores allows the viewers to see how these forms of violence operate on a daily basis. The multi-conflict can be seen in Diana Navarro’s tireless work to get sexual workers access to health insurance that would cover, among other things, HIV treatment. We can witness this conflicto as she gathers testimony from trans women who live on the Street and have suffered aggression from the police. The movements and permanent migrations are present in almost all of the life stories depicted. Whether they are from Venezuela or the Guajira, almost all of them have left home and have found a welcoming space, but at the same time transitory, in Tabaco y Ron, on their way to self-determination. Urban and structutal segregation is in the history of barrio Santafé itself. From its categorization in 2002 as a Special Zone for High-Impact Service, that, is, a zone in which sexual work is permitted, barrio Santafé is at the same time a refuge and a jail, as Gabriella Quillones, one of the trans women interviewed, says “In other parts of the city, they’d throw rocks at me,” adding, “[el barrio Santafé] is out cage, our little cage of queers.”

But Todas las flores also shows much more than experiences of violence and suffering. Indeed, the documentary weaves a nuanced, complex and diverse network of stories in which trans and cis people live together and take care of each other, and where, in spite of conflicts and tensions, the networks of trans support, happiness and resistance stand out. This can be felt int the images of the Trans Spring, a name for the Trans March that for years has been separate from the LGTBQ+ Pride March. The name derives from the slogan that also gives the documentary its title, “You can cut all the flowers, but you cannot keep spring from coming.”

The images we see are from 2018 when the Trans Community Network —one of the most important trans organizations in the country, founded by trans sex workers from barrio Santafé—met with the artists Tomás Espinoza and Artúr Van Balen to develop a process of collective creation. The result was a 50-foot latex balloon that represents the body of a trans woman, carried by hundreds of participants in the march. Daniela Maldonado, the Network’s founder, observed “To mak the body of a transwoman implies many things..,[the bodies of trans women] are bodies that stay in the barrio all the time and no one looks at them and no one cares what happens to these bodies, so that more than a visible, large body, which is a body that suffers all these forms of violence, but it is also a body that is the object of desire.” Like the barrio Santafé, and like the documentary itself, the Trans Spring is a space of congregation, struggle, resistance and memory, but also of joy and celebration of trans bodies and lives.

This atmosphere extended to the film’s presentation. Many of the people barrio Santafé who participated in the documentary attended the showing, so the movie theatre became a live space where the cries of “for those who are here, those who aren’t and those who are in danger” could be heard whenever one of the many departed friends appeared on the screen, mixed with laughter and exclamations of happiness in the face of mutual recognition and the certainty of a shared history.

Finally, Diana Navarro’s words echo in my mind, “Here there are many policies and many well-written laws, but if all this is not accompanied by processes of cultural transformation, they’re meaningless.” After watching the documentary, it became clear rhat many people have been working for this change, including multiple initiatives of the Trans Community Network, with Navarro Sanjuan herself working for decades, the community cooking pots to share with the entire neighborhood and the beauty queen pageants of Tabaco y Ron. Todas las flores comes to add to these efforts. The choral portrait, nuanced and inter-generational offers us at the same time homage and resistance to invisibilization and silencing, a gesture of dignifying and celebrating trans life which, as Carmen Oquendo-Villar says, is not just the demonstration of the very real and daily struggle for survival, but also highlighting the perpetual flowering of the trans spring.

Todas las flores

El eterno florecer de la primavera trans en Colombia

Por Juliana Martínez

La fila puede verse antes de llegar al teatro. Decenas de personas esperan impacientes en la taquilla para ver si aún es posible conseguir boleta. El ambiente es festivo. Personas de distintas generaciones y procedencias se saludan abrazándose, viejos conocidos se reencuentran, se escuchan risas escandalosas, y el sonido de tacones apresurándose a entrar llena el espacio. Es un día para celebrar, no solo porque es 28 de junio, día Internacional del Orgullo LGBTQ+, sino porque después de 17 años de rodaje por fin se estrena Todas las flores (2023), un documental que se centra en las vidas de las trabajadoras sexuales trans del barrio Santafé en Bogotá, Colombia.

Dirigido por la puertorriqueña Carmen Oquendo-Villar (una investigadora visitante 2018-19 en el David Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies), y producido por ella, Alejandro Ángel (Armadillo: New Media & Films, Colombia) y Annabelle Mullen-Pacheco (Belle Films, Puerto Rico y España), Todas las flores ofrece una mirada íntima a la comunidad que se teje en torno a Tabaco y Ron, un espacio multifuncional que ha acogido a generaciones de mujeres trans que allí encontraron un espacio seguro para socializar, trabajar y vivir. Como dijo Diana Navarro Sanjuan—una de las lideresas trans más importantes del país fallecida en 2022, y a quien el documental está dedicado—“Tabaco y Ron siempre ha sido un sitio emblemático para las mujeres transgénero que ejercemos prostitución porque fue la primera whiskería […] el primer sitio abierto al público que nos ofreció una oportunidad de ejercer prostitución dentro de su establecimiento a las mujeres transgénero. Incluso nos ofreció hasta vivienda […] y por eso a Guillermo algunas le dicen “La madre Guillermo”, porque Guillermo es como una madre sobre todas nosotras, las más antiguas, las que llegamos aquí en la época de los 80s”. Todas las flores es en entonces un retrato coral, multifacético y expandido en el tiempo de las vidas de quienes de una u otra manera han hecho de este espacio su hogar.

Pero esto no siempre fue así. Originalmente, la película iba a centrarse en Diana Navarro. Sin embargo, poco a poco Oquendo-Villar concluyó que más que de un retrato individual, se trataba de una historia colectiva compuesta por muchas voces a lo largo de los años. Así nació Todas las flores. Esto no quiere decir que Oquendo haya abandonado la idea de un largometraje sobre la vida y obra de Navarro Sanjuan. Aunque Diana ya no podrá verlo, el proyecto continúa y se encuentra en su etapa de postproducción.

Un mérito particular de Todas las flores es que rehúye la mirada exotizante, fetichista o etnográfica tan común cuando se trata de narrativas hechas por personas cis (no trans) sobre personas trans. Gracias a los vínculos que Oquendo desarrolló con las personas y comunidades que hacen parte del proyecto a lo largo de los muchos años de filmación, en particular con Diana Navarro, el documental habita el espacio de lo cotidiano, mostrándonos, sin idealizaciones pero también sin sensacionalismo, el día a día de quienes viven y trabajan en Tabaco y Ron.

Otro elemento inusual de Todas las flores es que presenta una mirada intergeneracional tanto del barrio como de las comunidades trans que han hecho de este su hogar. En una comunidad para la cual el promedio de vida en Latinoamérica es de 35 años, contribuir a rescatar y preservar las experiencias y testimonios de madres trans es un valioso aporte al ejercicio de memoria histórica que permite resistir las múltiples formas de silenciamiento e invisibilización que experimentan las mujeres trans, particularmente si se encuentran atravesadas por otras barreras como su clase social, racialización, el vivir con VIH y el ejercer el trabajo sexual.

Esta mirada diacrónica permite también entender cómo han cambiado, sin eliminarse, los distintos tipos de violencia que enfrentan las personas trans en Colombia. En este sentido resulta útil recordar el marco desarrollado por el Colective Virus Epistemológico para analizar la violencia y el cisexismo que enfrentan las personas con experiencia de vida trans. Como explico junto con mis colegas Helena Suárez Rodríguez y Franklin Gil Hernández en la introducción a nuestro volumen dedicado a los estudios trans en la Revista de estudios colombianos (No. 58, 2021), el Colective propone tres categorías: el multiconflicto, los movimientos y migraciones permanentes, y las autoprofecías, segregación urbana y estructural.

El término “multiconflicto” explica que, más allá de la violencia directa, “todo es un conflicto para las personas trans pues […] todas las vivencias trans están atravesadas por un conflicto: ir al médico, salir a la calle, disfrutar espacios que otros comparten, ir a un supermercado, entre otros” (Colective Virus Epistemológico, 2020, pág. 81. En Martínez, Juliana; Suárez Rodríguez, Helena y Gil Hernández, Franklin. Revista de estudios colombianos. No. 58, julio – diciembre, 2021, pág. 6). Al hablar de movimientos y migraciones permanentes, el desarraigo o la expulsión de sus familias, comunidades y territorios es una experiencia común para muchas personas trans que, además, suele repetirse por razones que van de la búsqueda constante de medios de subsistencia a la persecución violenta de fuerzas del estado, grupos al margen de la ley, u otros actores violentos. Finalmente, autoprofecías, segregación urbana y estructural, se refiere a cómo con demasiada frecuencia las personas trans son relegadas a sectores de la ciudad con altas tasas de pobreza, desempleo y violencia, siendo su sola presencia criminalizada y perseguida en otras zonas.

A través de la multiplicidad de historias que la conforman, Todas las flores permite entrever cómo operan estas formas de violencia en el día a día. El multiconflicto puede verse en el incansable trabajo de Diana Navarro intentando que las trabajadoras sexuales tengan acceso a un seguro médico que cubra, entre otros, el tratamiento del VIH, o recogiendo el testimonio de mujeres trans habitantes de calle que han sido violentadas por la policía. Los movimientos y migraciones permanentes están presentes en casi todas las historias de vida retratadas. Sean de Venezuela o la Guajira, casi todas han abandonado su lugar de origen y han encontrado en Tabaco y Ron un espacio acogedor, pero a su vez transitorio, en su camino a la autodeterminación. La segregación urbana y estructural está en la historia misma del barrio Santafé. Desde su categorización como una Zona Especial de Servicios de Alto Impacto en 2002, es decir, una zona en la que el trabajo sexual es permitido, el barrio Santafé es a la vez refugio y cárcel, pues, como dice Gabriella Quillones, una de las mujeres trans entrevistadas, “en otras partes de la ciudad me cogerían a piedra”, y añade, “[el barrio Santafé] es nuestra jaula, nuestra jaulita de las locas”.

Pero Todas las flores no muestra solo ni principalmente experiencias de violencia y sufrimiento. Por el contrario, el documental teje una red matizada, compleja y diversa de historias donde las personas trans y cis conviven y se cuidan mutuamente, y donde pese a los conflictos y tensiones, las redes de apoyo, la alegría y la resistencia trans sobresalen. Esto se hace palpable en las imágenes de la Primavera Trans. La Primavera Trans es el nombre que ha recibido la marcha trans que viene realizándose hace años de manera independiente a la marcha del Orgullo LGTBQ+. El nombre viene de la consigna que también da título al documental, “Podrán cortar todas las flores, pero nunca detendrán la primavera”.

Las imágenes que vemos son de 2018 cuando la Red Comunitaria Trans—una de las organizaciones trans más importantes del país, fundada por mujeres trans trabajadoras sexuales del barrio Santafé—se reunió con los artistas Tomás Espinoza y Artúr Van Balen para adelantar un proceso de creación colectiva. El resultado fue un inflable de látex de 15 metros que representa el cuerpo de una mujer trans, y que fue cargado por cientos de participantes el día de la marcha. Como dijo Daniela Maldonado, fundadora de la Red, “hacer un cuerpo de una mujer trans implicaba muchas cosas… [los cuerpos de las mujeres trans] son cuerpos que todo el tiempo están en el barrio pero nadie los mira, y a nadie les importa lo que les pase a estos cuerpos, entonces qué más que un cuerpo visible, grande, que es el cuerpo donde se atraviesan todas esas violencias, pero también es un cuerpo que muchas veces es objeto de deseo”. Como el barrio Santafé, y como el documental mismo, La Primavera Trans es un espacio de congregación, lucha, resistencia y memoria, pero también de gozo y celebración de los cuerpos y las vidas trans.

Esta atmósfera se extendió a la presentación de la película. En la sala estaban muchas de las personas del barrio Santafé que hicieron parte del documental, así que la función fue un espacio vivo donde los cantos de “por las que están, las que no están y las que peligran” que se escuchaban cuando aparecía en pantalla una de las muchas amigas idas, se mezclaban con los aplausos, las risas, y las exclamaciones de alegría ante el reconocimiento mutuo y la certeza de una historia compartida.

Al final, las palabras de Diana Navarro resuenan en mi mente: “Aquí hay muchas políticas y muchas leyes muy bien escritas, pero si todo eso no se acompaña de procesos de transformación cultural, no sirven para nada”. Después de ver el documental queda claro que son muchas las personas que han venido trabajando por ese cambio, incluyendo las múltiples iniciativas de la Red Comunitaria Trans, pasando el trabajo de décadas de la propia Navarro Sanjuan, las ollas comunitarias para compartir con todo el barrio y los reinados de Tabaco y Ron. Todas las flores viene a sumarse a estos esfuerzos. El retrato coral, matizado e intergeneracional que nos ofrece es a la vez homenaje y resistencia a la invisibilización y el silenciamiento, un gesto de dignificación y celebración de las vidas trans que, como dice su directora, no se queda en mostrar la muy real y cotidiana lucha por la supervivencia, y resalta sobre todo el perpetuo florecer de la primavera trans.

Juliana Martínez is an associate professor in World Languages and Cultures at American University, Washington D.C.

Juliana Martínez es profesora asociada en World Languages and Cultures en American University, Washington D.C.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

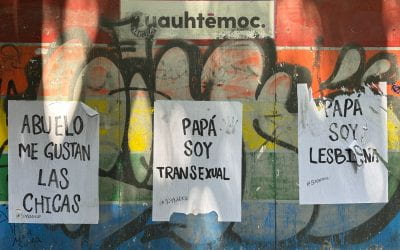

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.