Transportation for whom?

Building a more gender-equitable transportation system in Mexico City

It’s dark when Carmen wakes to the sound of her alarm clock. Preparing for the day, she packs her bag for work, makes breakfast for her children and fills their backpacks. After helping them get ready, she leads her children by the hand into the unlit street. She’s careful to steer them around the potholes and debris in the road—stepping to the side as cars rush by—and taking the long way around the bar ahead where men are often spilling into the street this time of morning.

When they reach the bus stop, she picks up her smallest child and offers her bag as a seat for her eldest. When the bus arrives, she lifts her children one-by-one onto the large step, pays three fares and, weaving their way through fellow passengers, ultimately presses into a space just large enough for her to stand with their bags between her feet, her youngest in her arms.

Getting off the bus eight stops later, they walk together to her aunt’s apartment, where the children will stay until she returns that evening. Saying goodbye, she retraces her steps, alone this time, returning to the bus stop and awaiting the next bus toward La Paz Metro station on the periphery of the Mexico City (CDMX) metropolitan area.

As she waits, she gathers coins for her fare, glancing up often to monitor the still-dark streets around her. She’s relieved to see the bus coming, but braces for her squeeze into the crowd on what she knows will be a busy early morning ride.

Arriving at the Metro station, she disembarks and walks through the sprawling station to her platform. She shifts her bag from shoulder to shoulder as she climbs three flights of stairs and navigates tunnel-like hallways, trying to avoid brushes by those rushing past. On the dimly lit platform, she wonders if she’s near enough the front of the crowd to make it onto the first train. When it arrives, she clutches her bag to her chest and jostles for a spot. It’s an uncomfortable squeeze, but she’ll be late if she misses this one.

With the seats taken and the hanging handholds beyond her reach, she depends on the press of nearby bodies for balance during the hour-long ride ahead.

After transferring to another line, she is now on her final train and three stops from her destination when she feels a hand slowly slide down her back. Frozen, she doesn’t dare turn. Heart pounding, her muscles tighten. Staring straight ahead, she recognizes the familiar landmarks of her stop as the train approaches. Pushing out of the car, she rushes up the stairs to the exit without a backward glance. Catching her breath on the sidewalk, she walks down the still-awakening streets of Zona Roma, making her way through the vendors setting up to greet the morning rush. When, 20 minutes later, she reaches the apartment building where she works as a maid, she is just starting to feel her heart slow, regaining her composure before beginning her workday. Carmen is a composite of findings from interviews with 13 gender and transportation scholars, policy makers, transportation planners and advocates based in Mexico City who recounted to me very real challenges faced by them and other women in Mexico City and elsewhere.

_________________

Every day, women in Mexico City, and especially low-income women, navigate a public transportation system that is inconvenient, unreliable, expensive and unsafe. This is, in large part, because Mexico City’s transportation system was not designed with the needs and travel patterns of women in mind. As in many other cities across the globe, Mexico City’s transportation systems were planned by and for male office workers, designed to provide linear, point-A-to-point-B connections between commercial and residential areas. However, women’s travel patterns, needs, preferences and experiences differ greatly from those of men.

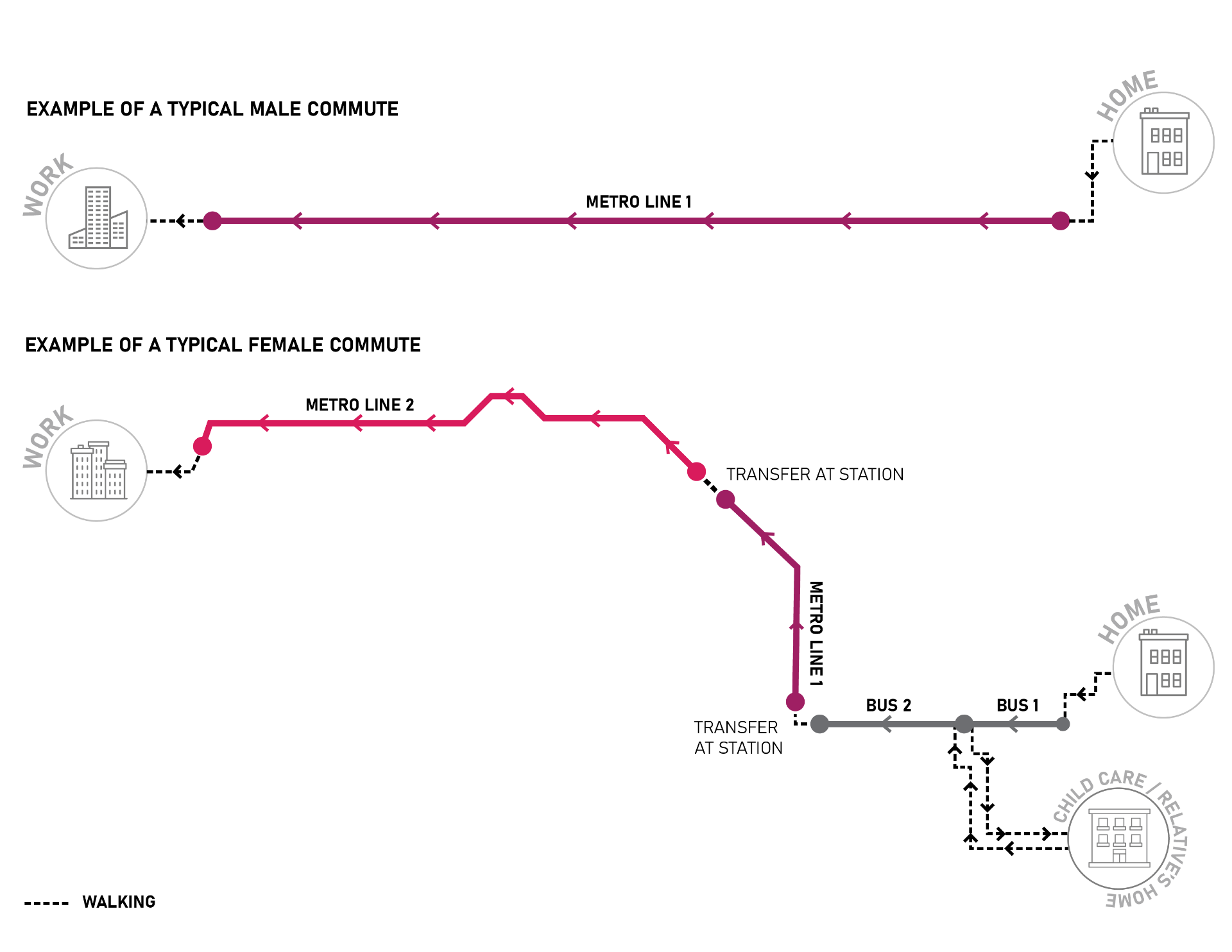

This is, in large part, due to the care-taking and domestic responsibilities women disproportionately assume due to cultural gender norms, what society expects of them. Because women are more likely than men to serve as caretakers, women are more likely than men to travel with others like children or elderly family members, as well as with bulky items like bags and strollers. Women’s care-taking responsibilities also mean women take more complex trips. While men are more likely to take linear trips to and from home and work, women often perform multiple tasks in a single trip, such as stopping to buy groceries and dropping-off a child at school on the way to work or to check on an aging parent on the way to a doctor appointment. Mexico’s 2017 census also reveals that men and women also travel for different reasons. For men, work is the primary reason for travel, while care-travel—trips related to caring for others or care-taking responsibilities—accounts for the largest share of women’s travel.

Census data also demonstrate that men and women get around using different modes of transportation. High-speed rail systems like the CDMX’s Metro are designed to efficiently and affordably serve the types of trips men often make—long-distance, linear commutes from residential areas to commercial centers in morning and evening hours. Women are more likely to travel to destinations closer to home to get to child-care, schools, or pharmacies, making multiple, short trips in a day. Thus, women are more likely to depend on buses that serve more local destinations. Because buses make many more stops than do high-speed rail lines and often share lanes with car traffic (with the exception of CDMX’s bus-rapid transit Metrobús line that occupies a dedicated bus lane), women end up depending on routes that take longer and are less efficient than the Metro. Men are also more likely to have access to cars or motorcycles or ride a bike, while women are more likely to walk to get where they need to go. Women are also more likely to take multiple modes in a single trip, like taking the bus, Metro and a taxi to get to and from a doctor’s appointment.

The diagram illustrates a typical trip to work by male and female residents of Mexico City, respectively. Due to societal gender roles, women’s travel patterns differ from those of men. Trips to care for others, such as trips to pick up or drop off children, account for the largest share of women’s travel, and women are more likely than men to take complex trips with multiple stops and modes of travel in a single journey. On the other hand, men are more likely to take direct trips between point A and point B and work accounts for the greatest share of men’s trips.

Finally, and perhaps most importantly, travel is especially dangerous for women in Mexico City. A landmark 2008 study by the National Board for the Prevention of Discrimination found that nearly all women (90%) had experienced sexual violence while using Mexico City’s transit system.

The threat of danger has real impacts on the way women plan their travel throughout Mexico City and many women have adapted travel behaviors to try and mitigate their risk of sexual harassment and violence. A 2018 study by ONUMujeres and Estudios y Estrategias para el Desarrollo y la Equidad (EPADEQ), found that 16% of women in Mexico City travel in groups, 15% avoid travel at night or early in the morning, 14% avoid walking alone, and 7% regularly and intentionally change their routes and travel patterns. Beyond this, nearly 40% of women report having adopted other measures to improve their safety while traveling through streets or on public transit.

Taken together, the gender inequities baked into Mexico City’s transportation system end up reinforcing gender roles and limit women’s opportunity, participation in civic life and ability to determine the course of their lives. However, not all women are affected equally. Low-income women are disproportionately impacted by the shortcomings of a public transportation system designed without women in mind. As in many North American cities, those who can afford to avoid public transportation do. Driving, rideshare and taxis offer efficiency, reliability and refuge from the threats of harassment and violence women face in the streets and on public transportation. While higher-income women can opt to avoid these challenges by driving a car or taking a taxi/using rideshare, low-income women bear the burdens of an inequitable system. Reports of taxi ridership in Mexico’s census data demonstrate that the challenges of public transportation mean some low-income women are also forced to seek more expensive modes like taxis to avoid these risks, incurring even greater proportionate travel costs than higher-income women.

The inefficiencies, cost and danger women face on public transportation in Mexico City has real societal and personal costs. Transportation is not just a means of getting around, but is essential to accessing quality employment, education, essential services and leisure. Conversely, the lack of reliable, affordable, safe transportation limits one’s economic and education opportunity, civic participation, and ultimately, ability to make decisions for oneself. This is especially true for low-income women who depend on public transportation. Because women are often the main or sole caretakers and parents in their households, women’s ability or inability to access services and opportunity can have generational ripple effects, shaping household income, children’s access to education and healthcare and more.

For all these reasons, a gender lens is essential to planning a truly equitable, inclusive public transportation system. As Paula Soto, a sociology professor at the Universidad Autonoma Metropolitana-Iztapalapa, explained during our conversation in early 2020, “without a gender perspective, public transportation seems like the safest way to travel” due to its regular and direct service and low cost relative to other modes. However, “with a gender perspective, you see it is the most dangerous.”

In 2007, the Mexico City took historic action to improve safety on public transportation. The public safety and transportation program “viajemos seguros,” now “viaja segura,” created women’s-only cars on the Metro during peak travel times. Many feminist groups and women’s rights advocates quickly adopted and championed the program, and in 2016, train cars and platforms were reserved for women throughout the Metro system 24 hour a day.

Women-only cars have helped reduce sexual harassment and violence on Metro train cars and the dedicated spaces have also increased access to travel for some women, including leisure travel like visiting other neighborhoods to see friends and family, Soto says. However, the ability of the women-only cars to address the root causes of sexual harassment and violence and the gender inequities in the transportation system is limited. Many worry that the women-only cars not only miss the root causes of gender inequity, but reinforce gender norms and further silo women’s role in the public realm. One senior transportation planning official at the Mexico City Secretary of Mobility (SeMovi) described this tension: “[the women-only cars] are for women, but [the program] was not executed with a gender-equity perspective…they send a message that the separation of genders is natural and that sexual harassment and assault is natural and inevitable.” The high visibility of the train cars, they argued, justified taking little other action to address cultural norms and transportation planning and design practices for over a decade. While the cars have proven an important stop-gap measure to curb immediate threats on the Metro, they were not paired with long-term strategy. The cars also do little to address risk beyond the platform’s edge, including the danger women face in the streets and traveling through stations.

The 2018 inauguration of Mexico City’s current mayor, Claudia Sheinbaum, ushered in a new, more integrated approach to gender-inclusive transportation planning and design in CDMX. Initiatives related to gender and transportation were moved from the domain of the City’s Secretary of Women to SeMovi, signaling a recognition of gender equity as a fundamental pillar of transportation planning. In 2019, SeMovi published the city’s inaugural Plan Estratégico de Género y Movilidad 2019 (Gender and Mobility Strategic Plan 2019), laying out a broad range of solutions across the entire transportation system.

One initiative in particular showcases the city’s commitment to moving beyond women’s cars to more cross-cutting solutions that address a host of gendered transportation challenges. In 2019, SeMovi began the process of redesigning CENTRAMs, or multi-modal transit hubs where multiple train and bus routes intersect. CENTRAMs play a particularly important role in the travel of low-income women who travel from the city’s peripheries and make many transfers to reach their destination. CENTRAMs will be redesigned to not just be spaces for safe passage, but for safe waiting in recognition of the time women spend transferring, waiting and traveling with dependents. Future CENTRAM design will increase the visibility of care work with accessible bathrooms and rest areas, include large central halls for visibility, have ample lighting and windows, and house destinations women frequent to reduce their trips, such as bill-pay stations. Despite SeMovi’s expansive view of the role of gender-equity in transportation planning, the agency recognizes the shortcomings of its planning to-date: the 2019 gender strategy leaves out those arguably most at-risk—transwomen and gender-nonconforming travelers.

SeMovi’s ongoing implementation of the 2019 gender strategy marks a growing global recognition of gender equity as central to building inclusive, accessible and affordable transportation systems for all and the urgent need for a gender lens to be embedded in all parts of the transportation planning, design, and construction process.

Fall 2021, Volume XXI, Number 1

Carolyn Angius is an urban planner based in Los Angeles, California, practicing at the intersection of planning, design, social justice, and gender equity. She can be reached at angiuscarolyn@gmail.com.

Related Articles

Editor’s Letter: Transportation

Bridges. Highways. Tunnels. Buses. Trains. Subways. Transmilenio. Transcable. When I first started working on this issue of ReVista on Transportation (Volume XXI, No. I), I imagined transportation as infrastructure.

Modernity in Black and White

For years, one of my favorite pieces in the Museo de Arte Latinoamericano de Buenos Aires (MALBA) was the iconic Abaporu (1928), by Brazilian artist Tarsila do Amaral: a canvas…

Transportation Itself Does Not Build Urban Structures

English + Español

Fina Rojas lives in the 19 de Abril at Petare, the densest and one of the largest self-produced neighborhoods in Latin America. Most researchers and policymakers define self-produced neighborhoods as “informal settlements.” However, these settlements occur from…