Vaccine Revolts

Public Health and the Politics of Rights in Brazil

In the past eight months, conservative Brazilian politicians have invoked rights against public health mandates at least twice. In June, Congresswoman Carla Zambelli falsely claimed that a federal bill allowed “unconstitutional home invasions” to enforce mask usage inside households. In November, President Jair Bolsonaro said that he would exercise his “right” not to get vaccinated against Covid-19.

Zambelli and Bolsonaro fueled controversies to keep their supporters engaged even as people continuously get infected and die. As of now, more than 190,000 Brazilians have been victimized by the pandemic.

The two politicians’ declarations brought me back to early-20th-century Rio de Janeiro. Then, the government implemented public health mandates that were not well received by the population. My research with newspapers and legal records reveals that individual rights were at the core of this resistance and its most well-known manifestation: Brazil’s 1904 Vaccine Revolt.

Between 1903 and 1909, to attract European immigrants and foreign investments, President Rodrigues Alves invested in public health and urban reforms that transformed Rio, then Brazil’s capital. To coordinate the reforms, Alves appointed physicians and engineers who claimed to be acting in the name of science – untainted by political interests.

To contain smallpox, yellow fever and other epidemics, state agents inspected and disinfected homes with sulfur, ordered evictions and vaccinated the population. To open space for Parisian-style buildings and avenues, they demolished unsanitary tenements and old colonial houses.

The “beautiful city”—as Rio is still known—was born through a violent process that displaced tens of thousands of mostly Black workers to distant rural areas or nearby hillside communities.

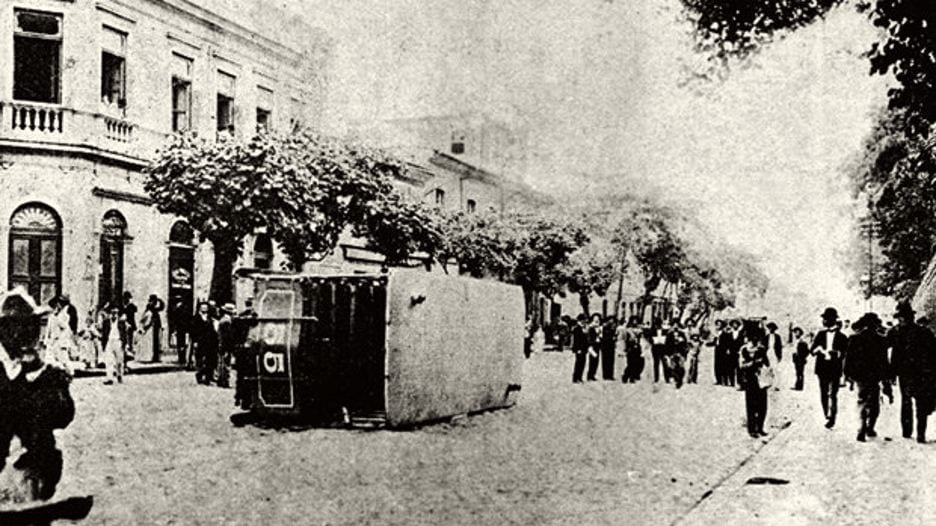

In November 1904, thousands of students and workers protested mandatory smallpox vaccinations. For six days, this crowd fought the police with stones and tools, flipping over streetcars to barricade the streets. President Alves reacted by mobilizing troops to crush the movement and detain alleged insurgents.

Historians debate why people resisted an effective method of disease control. Smallpox had devastated Brazil since the 16th century, and vaccinations were first implemented in the capital in the 1810s. Yet, only 2% to 10% of Rio’s population was vaccinated yearly. As a result, in 1904, smallpox killed 0.4% of the city’s residents.

Anti-vaccination sentiments rooted in popular and elite skepticism toward science had existed in Rio since the early 19th century. Alves’ segregationist urban plan had deepened the city’s housing crisis, creating widespread dissatisfaction among the poor.

A group of civilian and military radical republicans who opposed Alves’ government saw an opportunity in people’s discontent. In newspapers and public meetings, they fueled outrage with public health mandates to destabilize the capital and stage a coup. While common folks barricaded the streets, this group marched with young military cadets towards the presidential palace. Like the popular protests, the coup was quickly suppressed by the military.

The declarations of Zambelli and Bolsonaro brought me back to 1904. Not only because they “politicized” the pandemic—as others have—but because they did it by using a language of rights.

In 1904, those who opposed public health mandates also invoked individual rights.

The radical republicans who plotted a coup argued that reformers were “sanitary despots” who violated “individual liberties” to fulfill their scientific and economic interests. Liberal lawyers and politicians, though not involved in the conspiracy, invoked the individual freedom of choice over vaccinations.

This top-down rights discourse coming from influential voices certainly mobilized people. During public meetings, labor leaders helped explain this discourse to the workers who packed union headquarters and public squares. My research has begun to uncover how the language of rights resonated with these common folks.

Slavery was abolished in Brazil in 1888. In 1904, its marks were everywhere in the capital, from the mostly Black uneducated workers who received little pay or were unemployed to the racist attitudes of elites who depicted the povo (people) as ignorant and uncivilized.

Nonetheless, throughout the 19th century, when Brazil was a monarchy (1822-1889), slaves had kept courts busy. While Brazilian law did not recognize slaves as citizens, it did allow them to sue their masters to obtain freedom. In the process, Africans and Afro-Brazilians had become fluent in the language of rights.

After the republican proclamation of 1889, elections were restricted to a tiny minority of male citizens who could read and held high-income jobs or property. Yet, poor people used the courts to voice their concerns with police violence, private disputes and forced conscriptions, among other issues. Besides Africans and Afro-Brazilians, Portuguese, Spanish and Italian immigrants were frequent litigants.

Former slaves and newly arrived migrants also joined labor unions and workers’ associations that made early-20th century Rio a politically effervescent city. The language of rights was therefore both inside courts and on the streets, where strikes and other protests were common.

The people who stormed the streets in November 1904 never revealed their motives in print, thus making it harder for historians to figure out what they had in mind. Many newspapers depicted the insurgents as a dangerous mob that was being manipulated by the conspirators who plotted a coup.

However, the history of rights-claiming in Rio’s courts and streets provides context for a different interpretation. What if, instead of being ignorant and manipulated, people interpreted the rights-based opposition to public health mandates as part of their long-lasting struggles for freedom and inclusion?

In public speeches that mobilized protests and in court cases that followed the revolt, the right to the home’s inviolability stands out. The 1891 Constitution protected the home as an “inviolable asylum.” Republican legislation translated this constitutional protection into a series of restrictions on residential searches and entries.

In August, several labor organizations, including railroad workers, bakers and navy sailors, sent Congress a petition stating that “the home hadn’t been for a long time an inviolable asylum.” In November, on the eve of revolt, Vicente de Souza—an Afro-Brazilian socialist doctor and labor organizer—inflamed a crowd by calling the mandatory vaccination bill the “law of the home’s violation.” In courts, people invoked this constitutional right in attempts to prevent public health agents from disinfecting their homes with sulfur—a violent but effective method that killed the mosquitoes that transmitted yellow fever.

The home’s inviolability carried different meanings. Brazilian elites viewed the home as the private space where patriarchs controlled the lives of wives, children and servants. Many of these servants had been enslaved Black women, who continued to work in elite households after becoming free. The conservation of this private space was reflected in Rio’s elite’s resistance against state regulation of domestic service. When public health agents entered homes to disinfect them and vaccinate residents, they threatened this traditional sphere of patriarchal power.

Rio’s poor also held similar patriarchal values. Nonetheless, since the 19th century, their homes had been spaces of struggle. Slaves had fought for the rights to form families and live on their own. In both plantations and urban tenements, these spaces gave them some control over their lives and bodies. Homes allowed slaves and free Blacks to make life plans, form networks of solidarity and hide from masters. For free Africans and Afro-Brazilians in Rio, tenements provided harbor against illegal (re)enslavement. The home therefore could be a space of freedom.

Since the late 19th century, Africans and Afro-Brazilians had lived in close quarters with poor European immigrants. Both groups struggled against home precarity. Without legislation that regulated contracts, landlords arbitrarily raised rents and threatened tenants with forced evictions. At the same time, the police frequently invaded their homes to arrest alleged criminals and political agitators. The early-20th century reforms had made working-class homes even more vulnerable.

Defending a group of 450 men and women who were arbitrarily arrested after the revolt, lawyer Anselmo da Silva wrote that people had stormed the streets “aware of the Republican Constitution’s violations, and conscious of their natural rights.” In 1904, this language of rights resonated with century-old popular struggles for freedom and security.

Four years later, the number of smallpox victims doubled in Rio. The disease killed almost 1% of the population. This deadly learning experience shaped public health policies in Brazil.

Over the past century, public health agents have succeeded in taking vaccinations and other remedies across Brazil’s vast territory. The centralization of efforts that started in 1904 has become a modern administrative infrastructure that reaches even isolated parts of the Amazon rainforest. These efforts now include educational campaigns that have taught Brazilians to cherish vaccinations and health professionals. For decades, Brazilians have had access to vaccines that helped eradicate diseases such as smallpox and measles.

Since 1988, when Brazil transitioned into a democracy after 20 years of military dictatorship, this infrastructure has served the country’s Unified Health System (SUS). The SUS is a constitutionally-protected free public health system that provides basic care to the poorest Brazilians. The 1988 Constitution protects everyone’s rights to health care and a healthy environment, and mandates that the SUS must function with the participation of local communities. Despite all its problems, which include an endemic lack of resources to treat everyone with equal care, the SUS has been a beacon of democratic access to treatments for HIV-AIDS, Covid-19 and other diseases.

When politicians such as Zambelli and Bolsonaro invoke individual rights against public health mandates, they threaten to undermine a century of advances.

In December, the Brazilian Supreme Court decided that mandatory Covid-19 vaccinations are constitutional. This will likely allow restrictions on freedom of movement and access to buildings. The justices voted to protect the “preservation of individual and public health” and the “right of the collectivity.” Yet, immediately after the decision, President Bolsonaro declared that he would not impose any restrictions on people who refuse to get vaccinated.

The mainstream press and oppositionist politicians have been fighting Bolsonaro with a renewed faith in “depoliticized” science. The advances that scientists have made over the past century, and in the past months, prove that we must trust their recommendations. However, the Vaccine Revolt teaches us that “depoliticizing” science is also dangerous. In 1904, the advances of science-driven “apolitical” public health agents produced the unthinkable.

To fight the pandemic, Brazilians may need to re-politicize the vaccine. After a century of proven benefits, and despite recent setbacks, the vast majority of the population now supports vaccinations. Drawing on the constitutional right to a healthy environment, and on the state’s duty to foster democratic public health policies, they can mobilize a political movement for the right to vaccinations. Not only an individual right to be vaccinated, but also a diffuse right to live in an environment where the virus has been contained.

Pedro Cantisano (pcantisano@unomaha.edu) is Assistant Professor of History at the University of Nebraska – Omaha. He was born and raised in Rio de Janeiro, where he studied law and did extensive archival research. He holds a Ph.D. in History from the University of Michigan.

Related Articles

Brazil’s Vaccinated Democracy

In March 2021, former Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, a current presidential candidate, posed a pointed question in a speech lambasting President Jair Bolsonaro’s Covid-19 response. “Where is our beloved Zé Gotinha?” Zé Gotinha is not a respected public health expert or crisis manager

Broken Land: Climate Change and Migration in Guatemala

Broken LandClimate Change and Migration in Guatemala Santos Istazuy Pérez (right) sits in meditation during a group hike and workshop at a lush farm along with fellow Guatemalans and like-minded people from around the world including Germany and Uruguay. Photo by...

The Gift of Art

My dear friend, Colombian pioneer performance artist, Maria Evelia Marmolejo, (Cali, Colombia, 1958) whom I met during the research for the exhibition Radical Women: Latin…