Paraguay and its authoritarian warlike discourse against COVID-19

Ever since I began my university studies back in 2008, I’ve realized that Paraguayans greatly exalt war and authoritarianism. That makes me much like every social scientist who is dedicated to describing, analyzing and characterizing Paraguay. No matter what topic occupied our interest, the rhetoric has been the same: “the enemy,” “the need for order” or “one more battle to be fought.”

In this context, the current pandemic has not been the exception in how it has been treated.

I vividly recollect March 10, 2020. It was the date when the central government decreed a partial quarantine, one that included the suspension of classes and all activities involving gatherings of people, both in public and private events. A few days later, the ban was tightened: borders were closed, international flights were shut down, night curfews were imposed, and the streets and highways were restricted.

In light of this situation, my parents, two doctors who had suffered through the dark years of Stronism (1954-1989), considered the situation with an air of concern: “seeing the capital, Asunción, like this, seems like those times we lived in fear of the dictator and his cruel police,” They told me.

With the measures imposed, comparisons of the COVID-19 situation in warlike terms were increasing: “we will be morally victorious as we were in the dispute against the Triple Alliance” (Brazil, Uruguay and Argentina; 1864-1870), or “officially as with the Chaco War” (Bolivia; 1932-1935).

Joined in lockstep, on March 22, 2020, the covers of both printed and digital newspapers adhered to a single slogan that sought to encourage us in difficult times. Published on their front pageswas: “The Guarani strength will defeat the coronavirus.” The message appealed to the triumphalist character of a race, one that “could never be defeated.” I was thinking at the time, and still do today, about the lack of necessity to emphasize a spurious nationalism.

As a matter of fact, “the Guarani strength” was no more than a myth. That which established the idea of “an epic people in battle” or of a people with “extreme intelligence,” who in the process of conquest went for the pacific mixing with the Spanish instead of violent resistance.

Slovenian anthropologist Branislava Susnik (1920-1996) has scientifically dismantled such a concept. The harangue of the “Guarani claw,” consequently, would be an element that would strengthen xenophobia and intolerance, values so common in a country that denies fundamental rights to sexual and ethnic minorities, for example.

In addition, the attribution of hero qualities to government representatives comes to my mind. The head of the Health Department, Julio Mazzoleni, was given the moniker of “the Commander,” one who in his charge would have the doctors, as “soldiers in the first line of action.” Euclides Acevedo or the “Implacable,” the visible head of the Ministry of the Interior, has been the one who asked the population to comply with the restrictive measures. “In the event that someone violates quarantine,” he emphatically warned, “law enforcement officers will subdue the misfits.”

This brings to my mind the image of my mentor in Paraguayan history, Antonio Galeano. It was during the mornings in 2005, when I was far away from studying sociology. To be honest, I was studying electronic engineering, but with his critical perspective on reality, it was him who made me change my mind regarding my future career.

Galeano spoke then of “messianism” and “Manichaeism.” The passing of time for Paraguayans was an explicit sign of everything has been seen as good or bad; and, compellingly, it seems necessary to find a maximum leader to direct the nation’s plans.

In the collective imaginary, to cite a couple, Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (1813-1840)or Mariscal Francisco Solano López (1862-1870)represented this notion. Today we can see that the phenomenon has taken shape in the figures of Mazzoleni, Acevedo or the President of the Republic, Mario Abdo Benítez. The president asserted that “the Paraguayan people have been known for being warriors.”

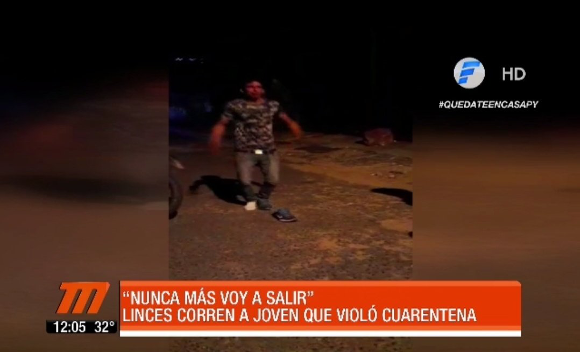

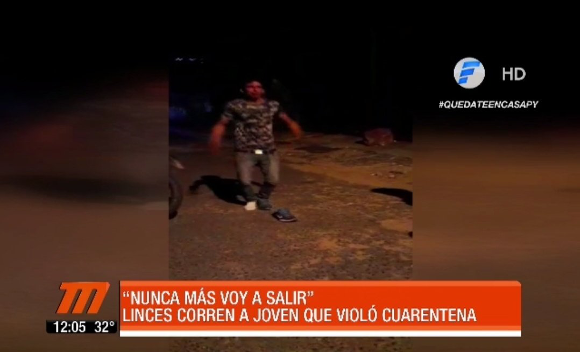

A few days ago, I observed with concern the actions of the motorized police known as LINCE. They appeared in news reports where they were shown subduing citizens who did not comply with the quarantine. The victims were compatriots, of scarce resources, many of them living in the streets, who were forced to exercise or threatened with Taser guns or with going to jail, for not respecting the stipulated norm.

In the face of these unfortunate events, some in the media praised the officers. “It’s what our country needs,” they declared. On social networks, an impersonal space in which citizens express themselves, some readers longed for the order and rectitude that characterized the dictator Alfredo Stroessner (1912-2006).

As the weeks go by in Paraguay, 40 days have come and gone. The specialists predict that the peak of infections will be reached in the third week of May. While those nostalgic for heroic deeds or tyrannical times are calling for a return to those times; the nation is facing the imminent danger of a general collapse. With just over 200 intensive care beds, no unemployment protection system or high government spending, concern seems to be elsewhere, a discursive one, of pitched battle against the new epidemic.

It’s 9 a.m., and as I write the final lines, I listen to the music “13 Tuyutí” by Francisco Russo in the distance. “A good song of war, of resistance, especially appropriate to raise the spirits of Paraguayans,” noted the morning show presenter. I ponder, from my purview, that after the pandemic nothing will be the same, but perhaps, and unfortunately, there still will remain that warlike and repressive culture that has done so much damage to us.

Click here (covid-20200421-wa0098.mp4) to view an example of the state’s recent propaganda to combat the threat of coronavirus.

Paraguay y su discurso bélico–autoritario contra el COVID-19

Por Carlos Aníbal Peris Castiglioni

Desde mis primeros estudios allá por el año 2008, me he dado cuenta que ha existido una fuerte exaltación a lo bélico y autoritario en la nación. Es decir, soy como todo científico social que describió, analizó y caracterizó al Paraguay. No importó el tema que haya ocupado el interés, la retórica fue la misma: “el enemigo”, “la necesidad de orden” o “una batalla más a pelear”.

Aquí, la pandemia actual, no ha sido la excepción en su trato.

Tengo un recuerdo vivo de ese 10 de marzo de 2020. Fue la fecha en la que el gobierno central decretó una cuarentena parcial, una que incluía la suspensión de clases y toda actividad que implique aglomeración de personas, tanto en eventos públicos y privados. Días posteriores la prohibición fue endureciéndose: cierre de fronteras, clausura de vuelos internacionales, toque de queda nocturno y mayores intervenciones por las calles y rutas.

A la luz del panorama ostentado, mis padres, dos médicos que han padecido los oscuros años del stronismo (1954-1989), deliberaban con un aire de preocupación: “ver así a la capital, Asunción, parece esas épocas que vivíamos con miedo al dictador y su cruel policía”.

Con las medidas impuestas, iban en aumento, a su vez, las comparaciones de la situación del COVID-19 a términos de una beligerancia total. Una en la que “saldremos victoriosos moralmente como lo hicimos en la disputa contra la Triple Alianza” (Brasil, Uruguay y Argentina) (1864-1870), u “oficialmente con la Guerra del Chaco” (Bolivia) (1932-1935).

Bajo una única consigna, el 22 de marzo de 2020, tapas de los diarios impresos y digitales se sumaron a un eslogan que buscaba alentar en tiempos difíciles. Exponían en sus portadas: “La garra guaraní vencerá al coronavirus”. El mensaje apelaba al carácter triunfalista de una raza, una a la que “jamás le pudieron doblegar”. Pensaba en el momento, aun hoy lo sigo haciendo, sobre la innecesaria imperiosidad de acentuar un falaz nacionalismo.

De hecho, “la garra guaraní” no fue más que un mito. Aquella que ha instalado la idea de “un pueblo épico en ofensivas” o “de una extrema inteligencia”, en el proceso de conquista, que se decidió por el cruce pacifico con el español antes que la resistencia violenta.

La antropóloga eslovena Branislava Susnik (1920-1996), científicamente, ha desmontado a tal concepto. La arenga de la “garra guaraní”, consecuentemente, sería un elemento que potenció la xenofobia y la intolerancia, valores tan usuales en un país que niega derechos fundamentales a minorías sexuales y étnicas, por ejemplo.

A lo dicho, además, se me vienen las heroificaciones acaecidas a los representantes del gobierno. El titular de la cartera de Salud, Julio Mazzoleni, fue asignado con el mote de “el Comandante”, uno que a su cargo tendría a los médicos, “soldados en la primera línea de acción”. Euclides Acevedo o el “Implacable”, cabeza visible del Ministerio del Interior, quien ha sido el que pidió el acatamiento a la población de las medidas restrictivas. “En el caso que alguien violare la cuarentena”, lo advertía enfáticamente, “los agentes del orden someterán a los inadaptados”.

Aparece la imagen de mi mentor en Historia del Paraguay, Antonio Galeano. Eran las mañanas de 2005 y me encontraba muy lejos de seguir sociología. Para ser sincero, estaba en las aulas de Ingeniería Electrónica pero fue él, y su perspectiva crítica de la realidad, los que me hicieron cambiar radicalmente la elección de mi futura profesión.

Galeano hablaba entonces del “mesianismo” y el “maniqueísmo”. El trascurso del tiempo, en el paraguayo, fue una muestra explicita que todo se ha visto en bueno o malo y, obligadamente, pareciera necesario hallar un máximo líder que dirija los designios de la nación.

En el imaginario colectivo lo fue, solo por citar, Gaspar Rodríguez de Francia (1813-1840) o el Mariscal Francisco Solano López (1862-1870). Hoy se vislumbraría que el fenómeno ha tomado forma en las figuras de Mazzoleni, Acevedo o del presidente de la Republica, Mario Abdo Benítez. El mandatario que aseguraba “el paraguayo se ha caracterizado por ser guerrero”.

Jornadas atrás, como último punto a resaltar, observaba con preocupación el accionar de la policía motorizada denominada LINCE. Aparecían en noticias en las cuales se les exhibía sometiendo a ciudadanos que no cumplieron con la cuarentena. Las víctimas eran compatriotas, de escasos recursos, muchos ellos que vivían en las calles, que fueron obligados a hacer ejercicios o amenazados con Táser o a ir a la cárcel, por no respetar la norma estipulada.

Ante los funestos actos, algunos medios de comunicación realizaban alabanzas a los oficiales. “Es lo que se necesita en el país”, aseguraban. En las redes sociales, espacio impersonal en el cual la ciudadanía se expresa, ciertos lectores añoraban el orden y rectitud que caracterizó al dictador Alfredo Stroessner (1912-2006).

Pasan las semanas en el Paraguay, ya van 40 días. Los especialistas afirman que en la tercera semana de mayo se alcanzará el pico de la enfermedad. Mientras que los nostálgicos de gestas heroicas o tiempos tiránicos piden el regreso a esas épocas, la nación se encuentra frente a un inminente peligro de colapso general. Con un poco más de 200 camas de terapia intensiva, sin un sistema de protección por desempleo o un alto grado de gasto estatal, la preocupación pareciera estar en otro lado, uno discursivo, de batalla campal contra la nueva epidemia.

Son las 9 a.m., escribo las líneas finales, escucho en lo lejos la música “13 Tuyutí” interpretada por Francisco Russo.“Una canción bien de guerra, de resistencia, especial para alzar el ánimo de los paraguayos”, afirmaba el presentador del programa matutino. Medito, por mi parte, que después de la pandemia nada será igual pero quizás, y lastimosamente, aun haya quedado en el pensar esa cultura bélica y represiva que tanto daño nos ha hecho.

Clic aquí (covid-20200421-wa0098.mp4) para ver muestra de propaganda del estado paraguayo frente a la amenaza del coronavirus.

Carlos Aníbal Peris Castiglioni, professor and researcher at the National University of Asunción – Paraguay. Director of the Social Sciences Department in the Faculty of Philosophy at the Catholic University of Paraguay. Former Director of the Rectorate’s Postgraduate Department at the National University of Asuncion (2016-2019).

Carlos Aníbal Peris Castiglioni, profesor e investigador de la Universidad Nacional de Asunción – Paraguay. Director del Departamento de Ciencias Sociales de la Facultad de Filosofía de la Universidad Católica del Paraguay. Ex director de la Dirección de Postgrado del Rectorado de la Universidad Nacional de Asunción (2016-2019).

Related Articles

A Review of Cuban Privilege: the Making of Immigrant Inequality in America by Susan Eckstein

If anyone had any doubts that Cubans were treated exceptionally well by the United States immigration and welfare authorities, relative to other immigrant groups and even relative to …

A Review of Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle

James Loxton’s Conservative Party-Building in Latin America: Authoritarian Inheritance and Counterrevolutionary Struggle makes very important, original contributions to the study of…

Endnote – Eyes on COVID-19

Endnote A Continuing SagaIt’s not over yet. Covid (we’ll drop the -19 going forward) is still causing deaths and serious illness in Latin America and the Caribbean, as elsewhere. One out of every four Covid deaths in the world has taken place in Latin America,...