Arturo’s (After) Lives

Gender Transgression in the Argentine Archives

Archivo General de la Nación (Argentina). Photography department. Code: AR_AGN_DF_CC_0259_CC_405344_A. Series: Ladies’ figures.

While writing a monograph about the histories of gender transgression in Argentina, I found photographs of Arturo de Aragónin the national archives (AGN). He was in a folder that defined him and many others—with words that sounded to me like pure sarcasm—under the terms figuras de damas (ladies’ portraits.) Since then, I’ve been reflecting on Arturo’s conflictive afterlives in tabloids, the archive and scholarship, to examine the challenges of seeking what maybe today we would potentially define as trans lives before the words that made sense of this experience even existed.

The photo above is one of the eleven photographs of Arturo de Aragón (sometimes also called Conde Augusto de Aragón) published by the popular magazine Caras y Caretas in 1906 and 1930. In each of them, Arturo posed with the characteristic suit of the time, embodying what was considered a male attitude in Buenos Aires in the first decades of the 20th century.

A Life in Tabloids

People first read about Arturo in 1906 when Caras y Caretas published an article with several photographs that the journalist Aquiles Escalante introduced as follows: “Here are photographs of an interesting subject that in the view of readers will appear as a fresh fifteen-year-old adolescent, but in fact, she is just a young lady, whose neatness, along with one of those resolutions that only women, friends of extremes by temperament, know how to adapt, has led her to conceal herself with such admirable perfection that she has been a man for ten consecutive years.”

Arturo was defined as a mujer-hombre [a woman-man,] a popular and perhaps offensive term by which journalists usually define those people transgressing the frontiers of gender from female to male (I previously wrote about another similar case in 1930.) In the first decades of the century, photographs and stories about mujeres-hombres multiplied in tabloids and medical journals, usually accused of being a fraud for stealing men’s lives.

During those years, Buenos Aires was transforming quickly as it integrated into the global market. Along with the development of new infrastructure and a growing transatlantic migration to respond to the demand for labor, Argentine elites since the late 19th century had hoped that Europeans would help civilize and whiten the country. Their initial hopes transformed into disappointment. Physicians, writers, lawyers and journalists expressed increased anxiety about the pernicious effects of immigrants and their potential negative impact on national development. The dream of developing the country through increased population growth through sexual reproduction soon translated into anxiety articulated in the hyper-awareness about the lives of so-called deviants, such as mujeres-hombres, sex workers, homosexuals and sexual inverts. Many of the stories of mujeres-hombres and sexual inverts started with transnational migration. It is impossible to know if these were those who called the attention of the authorities surveilling the new-come population or if these journeys were an opportunity to craft a new life of their own. Protected by the anonymity of a growing city, these new subjects brought the worst nightmare to the illusory dreams of progress of the elites.

According to Escalante, Arturo was born in 1882 in Italy to a family with a good social reputation. When the photo was taken, he was 24 years old, posing alongside his friends in male attire while projecting a confident and masculine demeanor in public settings. The journalist explained Arturo’s transformation by saying that he had been sexually assaulted at age 14. This story became a validation to legitimate his male transgression, considered a fraud.

Mobility—with these people usually moving from one job and city to another—characterized these stories of mujeres-hombres. These cosmopolitan figures threatened the Argentine nationalist fervor that arose in response to the disillusionment of the immigrants. Thinking from the perspective of our own times when visibility has become the ultimate goal of LGTBQ+ politics, it’s hard to imagine a time when invisibility and anonymity were sought after. Migration and the metropolis provided the possibility for reinventing one’s life.

While exploring the archives, I found multiple examples of people forging their documents by simply crossing a border to get a document certifying a gender difference on a birth certificate. These transitions usually changed people’s economic and romantic opportunities. What we understand as the total erasure of these lives from the traditional archives is possibly not more than the result of people who were able to avoid journalists, police officers and doctors to live on their own terms. In that sense, not being visible could also be a powerful opportunity.

The journalist described Arturo as a comic actor and political activist who agitated throughout France until moving to Buenos Aires to work as a sailor and a longshoreman in the barracks. Like many other male immigrants of his generation, he crossed the Atlantic more than once; the magazine described trips to London to work on meat imports, then returning to Argentina to seek employment in corn harvests and construction.

Broke and without a source of income, he decided to work as a policeman, which explains how, like other immigrant mujeres-hombres, he could get his legal documents identifying him as a man. Arturo made himself famous as a lover; journalists usually were concerned about the pernicious effects mujeres-hombres could have over the local women. According to an article published in Caras y Caretas decades later, Arturo ended up abandoning his life as a man after a woman broke his heart, perhaps as a reaction to social sanction or simply because his/her boundaries between masculinity and femininity were flexible. During these two decades, journalists used Arturo’s life as a mechanism to make moral judgments on those crossing the frontiers of gender.

Archivo General de la Nación (Argentina). Photography department. Code: AR_AGN_DF_CC_0259_CC_405343_A. Series: Ladies’ figures.

A Life in the Archives

After his death, Arturo’s life continued in the archives. First in a private archive used by Caras y Caretas journalists, and decades later in the biggest public archive of the country: the Archivo General de la Nación. These photographs, as all the other portraits of mujeres-hombres, relocated them in what the archivist considered the nature of their alleged artificial performance—one reduced to their genitalia. The reproduction of the original catalogue of the magazine holds Arturo’s life in a comic movement in a dissonant folder; his male posing and aesthetic perturbed the title of the folder “Portraits of ladies,” an act of state sovereignty over the male traces of Arturo’s (and many others’) lives. In fact, I couldn’t find any of what nowadays we would call a cisgender woman in that folder.

I was at the airport when I got the email from the AGN containing many of these portraits. The first excitement quickly faded to give space to frustration. People working on queer and trans histories would understand me. It is very difficult to capture the lives of people moving between gender using fragmentary materials that usually speak more about the elites’ anxieties than the words and experiences of those challenging the established order. Historical narrative demands stability, usually incapable of capturing fluid experiences that are placed in a totally different system of gender and sexuality. Even when portraits could usually express much more about the portrayed people’s desire, the production and archiving of the document work in a cryptic way. The cruel reality of archiving (the human selection of what survives time) is that we usually deal with categories produced by extreme inequality; the words of journalists, physicians and police officers survive time.

I am not writing anything that hasn’t been addressed in previous works. Recently, I have been using the concept of a “ruthless” archive to name the chaotic reproduction of the languages with which people were cataloged through the documents. Even if we have seen an increasing over-projection of rationality to the archive (a topic even subject to several memes), I think of a ruthless dynamic to make sense of the prevalence of the relationship of power in chaotic ways. Institutions such as the AGN organized material preserving the hierarchies and unequal power conditions contained in the documents, which usually erase how people would like to be remembered (something, in fact, impossible to know.) Being aware of the own language of the archive can be, luckily, the starting point to finding the fragmentary traces of queer and trans lives (for example, the word mujeres-hombres, helped to find many other cases.)

Archivo General de la Nación (Argentina). Photography department. Code: AR_AGN_DF_CC_0259_CC_405342_R /AR_AGN_DF_CC_0259_CC_405344_R. Series: Ladies figures.

This contrast between the potential desire portrayed and the encryption of those archived is clear when we see both sides of the photographs. On one face, we can see the numerous movements involved in Arturo’s male affirmation: the pose, clothing, his portrayal with friends and pursuit of male activities in public and private spaces. On the reverse (as in the media,) the inscriptions open a battle for portraying his life as an artificial mechanism: “Un nuevo caso de una mujer hombre” [A new case of a woman-men] or “tiene cara de muchacho bonachón la mujer hombre que murió misteriosamente” (“has the face of a handsome man, the woman-man who died mysteriously.”)

Archivo General de la Nación (Argentina). Photography department. Code: AR_AGN_DF_CC_0084_CC_370344_R. Series: Ladies’ figures.

While referring to another famous contemporary tabloid character called La Princesa de Borbón, usually accused of artificially living a female life, someone wrote in the backdrop of the photograph the word puto (faggot) [lately crossed] with its inscription later replaced with her name. Saying that archives have a chaotic and ruthless dynamic doesn’t make them static places. They are always scenarios of conflicts. In the last decade, the multiplication of queer/trans public projects such as the Archivo de la Memoria Trans in Argentina—a unique archival project led by the trans community—also fostered interesting exchanges of knowledge and reclassification of documents. These conversations are expressions of profound epistemological transformation that make other possibilities of rememoration and storytelling available.

The Lives on Scholarship

I heard of Arturo’s life long before finding the photographs. His life was and still is the inspiration for many authors. In his history of homosexuality in Argentina, the journalist Osvaldo Bazán inscribed his life in the genealogy of gay and lesbian history—usually naming Arturo after his female birth name. More recently, authors such as Francisco Fernández Romero and Andres Mendieta have placed him in the genealogy of trans masculinities in Argentina.

Globally, queer and trans historians debate about where we should place lives that don’t fit into our understanding of gender and sexuality. In her book about transgender childhood, Jules Gill-Peterson points to a an ongoing disagreement over the viability of including early 20th-century figures in trans genealogies, rather than identifying them as lesbian or gay, because of the lack of clear separation between categories of gender and sexuality. I don’t think this article is the place to engage with a discussion that I do widely in my forthcoming monograph; rather than placing people in static boxes, I think we could follow Susan Stryker‘s trans-historic exploration of documents; this is paying attention to those “people who moved away from the gender they were assigned at birth, people who cross the boundaries constructed by their culture to define and contain that gender.”

The fact that, according to magazines, Arturo’s crossed this boundary twice, something that could be as true as a fantasy that he sold to the tabloids, could hypothetically bring us the uncomfortable reality of writing. Writing demands stability—the simple fact that we need to name someone is always a risk because it can be difficult to capture the potentially shifting notions of selfhood (in times when they worked in very different ways than they do today.) Hypothetically, we could think this fluctuation is due to social pressure, a lie, or even a decision. Here I took the risk of narrating Arturo’s life based on the names that he apparently picked to describe a long period of his life. I usually start by distrusting those who, in the past, labelled and portrayed others’ lives as artificial. In this case, I can only say that there are eleven photographs in which Arturo embodied the most beautiful male features of his time. Why should I trust more in the names written by a journalist on the back of the document than in Arturo’s portraits?

Writing about these lives, with their few encounters, that moment of exposure that did away the freedom of anonymity will always be uncomfortable. Writing is always a risk. In this case, I tried to bet against those who tried to mock Arturo’s life because I believe in the potential effects that these living histories could have in the present. Maybe these uncomfortable decisions, these impossible encounters of knowledge, can open more than epistemological reflections but bring the light from the past to illuminate other potential joyful futures.

Patricio Simonetto is a Lecturer in Gender and Social Policy at the University of Leeds. His forthcoming monograph is titled A Body of One’s Own. A Trans History of Argentina (University of Texas Press, 2024.)

This project has received funding from the European Union’s Horizon 2020 research and innovation program under the Marie-Sklodowka Curie grant number 886496.

Related Articles

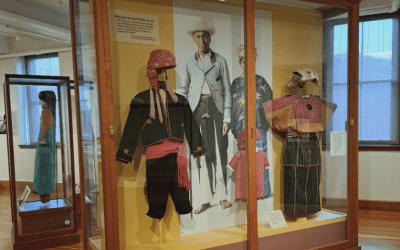

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

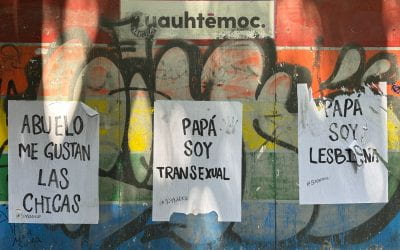

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.