Queer Lessons on Latinx Methods

“A Nation Will Never Protect Those Whom it has Tried to Eliminate.” So declared AfroIndigenous artist Alán Peláez López in their February 2023 exhibit at Harvard’s Smith Center Arts Wing. Named “N[eg]ation,” or nation-negation, the exhibit underscored how bodies Black, brown and Indigenous, queer, trans and non-binary, are in the nation, but not of it. To do so, “N[eg]ation” repurposed once-viral memes, deploying them to critique whitewashing discourses of mestizaje and transphobia. It placed blank canvas flags, staked in dirt, demanding viewers write what they’d give up for a post-Latinidad future. It constructed a makeshift graveyard of headstones and plaques telling the unheard hi/stories of Indigenous massacres in Argentina, of public executions of enslaved Black people in New Spain, of the deportation and incarceration of Japanese Peruvians. Convening disparate and interactive mediums around the racist violence enacted by nation-states on their most vulnerable populations.

I was particularly struck by a series of carmine tapestries hand-stenciled with convictions that, beyond the “A Nation Will Never Protect” declaration, included “Betrayal as an Act of Resistance to a Latinidad that Continuously Betrays Black, Indigenous, Asian, Queer, Trans, Poor, Fat, and Disabled Latinxs/es,” and “Who Are You Outside Your Nationality?” Confronting viewers upon entrance, however, was one tapestry in particular that declared “Latinidad is Cancelled.” For those of us familiar with the Oaxaca-born artist’s work, “Latinidad is Cancelled” harkens to a 2019 debate originating on Instagram indicting the anti-Blackness of the identity category that has unevenly embraced certain Latin American subjects in diaspora, while making more concrete the very boundaries of Latin America along the way.

“N[eg]ation” extends this project while expanding its visual registers, “symbolically and discursively interrupt[ing] the violent process of nation-making through a series of objects that call attention,” as Atlanta-based arts writer Ra Malika Imhotep writes, “to silenced histories and gesture towards alternative futures where Indigenous, Black, and Asian Latinxs live safely.” These alternative futures are ones where the nation is a buried relic, where networks of solidarity and care and joy are our animating structures, where—as another art object compelled—“hay personas negras, no hay poli-migra, hay personas negras, no hay prisiones, hay personas negras.” This future, in Peláez López’s work, radiates with a queer potential by deviating from the world as we know it, by manifesting a necessary alternative. In doing so, “N[eg]ation” creates its artistic crescendo both urgent and moving. Outside of the gallery and in the seminar classroom, “N[eg]ation” creates a series of generative problems for students and practitioners of Latinx history and literature.

At the same time Peláez López signals the trenchant racism and nationalism of Latinidad, they also underscore a series of practices—of actions, both intellectual and historical, that uphold these racisms and nationalisms. This begs a meditation on the importance and impact of not just who and what latinidad lets in and keeps out, but how latinidad is. In other words, how the central concepts of Latinx are sustained by what we do with them, what we do to them, even as those actions are thought to be responsive to instead constitutive of latinidad and literature alike. The problem, then, lies with Latinx methods.

Beginning at the cancelation of Latinidad, moving through the negation of the nation, and arriving at method might seem like an illogical progression. It is made more legible in light of lessons taught to us by queer artists and theorists. After all, queer studies runs parallel to Latinx Studies’ by performing critical introspection and necessary recalibration, all the while remaining a bit too method shy. Take, for example, the work of theorist Heather Love, whose recent Underdogs: Social Deviance and Queer Theory (2021) underscores queer scholarship’s opposition to “the methodology, epistemology, and ethics of the social sciences.” Love asserts that the equating of “social scientific method with objectification, social control, and state violence” led the field away from Sedgwick’s Touching, Feeling (2002)—which draws heavily from US psychologist Silvan Tomkins’ work on affect and the cybernetic fold—towards the “deconstructive queer lineage” of philosopher and theorist Judith Butler’s Gender Trouble (1999). Sketching a bit of a Copernican shift for queer studies and its foundational figures, Love’s project makes me question how unsettling Latinx Studies’ predilections for certain frameworks and readings—confronting our own method myopia—might similarly open up other lines of inquiry while bringing others to a necessary close.

In “Latinx, 1492 to 2022,” an undergraduate seminar I recently convened in the History & Literature program in conjunction with “N[eg]ation,” similar questions arose: what are Latinx Studies’ methods? How have the actions of historians, literary critics and cultural creators—their methods, what they’ve done and not done—contributed to the erasure of Blackness, the appropriation of indigeneity, and the dominance of heterosexuality and gender binaries within Latinidad? What methods exist or might exist to disrupt these attachments, to imagine otherwise?

As a collective, we took Peláez López’s acts of cancelation, negation and betrayal as starting points, as models of methods at once analytical, historical and aesthetic. Analytically, these emerged as methods of critique that pinpointed attachments to social formations resulting from and nourishing racism and cis-heterosexism, that confluence of cis-gender and heterosexual norms. These also functioned as methods of historiography, that is, as frameworks that organized and facilitated the reconsideration of dominant national and political discourses. Finally, these operated as methods of aesthetic interpretation that read literary and cultural texts participating in various global imaginaries, training attention to formal components and qualities and their impacts (indeed, implications) in racist, nationalist and cis-heterosexist structures.

In doing so, method came to signify an organizing operation that reveals components it deems important while informing us what to do with them. The course itself, then, became a practice in method-making. Instead of dictating methods to students, I encouraged them to detect what other methods were already tacitly at play in the field, asking what the impacts would be of calling them to consciousness, naming them and reproducing their maneuvers.

Unsurprisingly, thinking on method filled our seminar with new challenges. For me, and especially since students most freely associated method with the scientific method and ethnographic research, protocols less equipped for the history and literature classroom: how to explode method beyond those elementary associations? How to deliver this information concretely, to model the meta-analysis of method, without prescription? For students: how to loosen the grip on the what and who in favor of naming the how? And, when that how did not provide its name, how to bestow a name, and by extension, novel theoretical terms of engagement?

Reading across the times and spaces of the Américas proved generative. Thinking with Bartolomé de las Casas and Dora the Explorer, one student inaugurated exploration as method to show how texts about exploration position the reader/viewer as explorers, reenacting colonial “discoveries” of indigenous tribes and tropes that leave them exotified and anachronistic. On the heels (or at the throat?) of José Vasconcelos, another read eugenics as a method of historiography to explain the absence of Asianness from Mexican cultural imaginaries, despite documented populations of Chinese immigrants throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. The following entries, authored by students from past History & Literature seminars, demonstrate novel methodologies in more detail.

Rethinking major concepts in trans studies, Kris King, for example brings transing to the fore, resuscitating the inherent dynamism of transness and bringing it to bear on the migrating subjects of Latinx America. With migration akin to transitioning, and refusing the unidirectional narratives of gender transitioning, King shows how the lens of transing can destabilize Latinx, insisting it account for the myriad localities and specificities otherwise excised by the North American identitarian formation that awaits.

Nina McCormack, reading Puerto Rican poet Raquel Salas Rivera’s 2020 X/Ex/Exis: para la nación, demonstrates how monstrosity as method repositions both trans and cuir Puerto Rican subjects. Monstrosity moves beneath the verses of the poem “They” as the trans poetic voice confronts how their deadname, or assigned, pre-transition name, does not die but instead fuels a living, formatively zombie-like condition. Finding monsters in the closet(ed), McCormack also looks under the bed of empire to locate in Puerto Rico another generative monstrosity, one wending between the death sentence of U.S. imperialism and the vitality of queerness.

Inspired by the writings of two-spirit artist and writer Iván Monalisa Ojeda, Lea Han considers on the notion of a double life. Enacted as method, the double life facilitates an engagement with ways of being that have been occluded and sublated by reductive identities. Han moves across Monalisa Ojeda’s work, Los Angeles-based enclaves of Korean Guatemalans, and Piri Thomas’ iconic Nuyorican memoir Down These Mean Streets to reveal the double lives that live between normative genders and national and racial categories.

It’s hardly coincidental that these method meditations emerge inspired by and with trans subjectivities and hi/stories of Latinx America, as ways of being and knowing and creating that have been systematically overlooked. This affirms that inherited methods are not only inadequate but antagonistic to approximating and appreciating the impact of these subjects and hi/stories. Read in conjunction with each other, the articles that follow attest to the generative work of refusing the exclusion and erasure of Black and Indigenous Latinxs at their confluence with queer, trans and undocumented subjects in the Américas.

They also underscore the importance of placing artistic production at the heart of theoretical engagements with Latinx histories and cultures. In order to understand the ways in which Latinidad has disavowed Blackness and erased indigeneity, we must look beyond the canon to the anti-canonical, or to a still-emerging set of art objects and practices intent on contesting limited notions of ethno-racial Latinx belonging. As a result, the analytical capability of identifying these socio-cultural lacunae requires the development of creational capabilities too, ones where students turn to artistic modes of production to counteract these exclusionary dominant historical-cultural narratives through novel praxes, ways of undoing, doing, and redoing and (re)acting.

Tommy Conners is Assistant Professor of Latinx Studies and World Languages & Cultures at Allegheny College. Prior, he was lecturer of History & Literature and Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies at Harvard. He acknowledges with gratitude how support from the Elson Family Arts Initiative Fund and the Open Gate Foundation made bringing “N[eg]ation” and Alán Peláez López to the Harvard campus in Spring 2023, and by extension, these method meditations, possible.

Related Articles

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

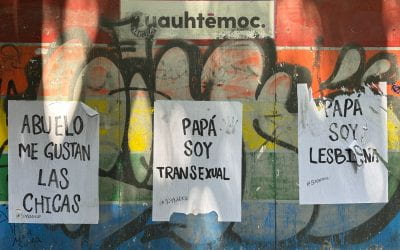

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.