Between the Sacred and the Profane

On Girls’ Culture in Lima

My childhood and adolescence in Peru were defined by my schooling experience in the first decade of the 2000s.

The experience of schools in Lima is characterized by hermeticism and zeal. There was a custom of privileging education from Catholic schools, both for girls and boys. There are also, of course, public and foreign schools in our panorama. Even in our literature, military schools are often portrayed, such as the Leoncio Prado in The Time of the Hero (1963). But, until the early 2000s, a Catholic, conservative, and homosocial education prevailed.

I was educated in a Catholic and female school. Third generation in an all-girls school; second generation in a Catholic all-girls school. It is a privilege to study when one is aware that until three generations ago my maternal great-grandmothers—one from a landowning family in the highlands, and the other, a first-generation Chinese migrant born in Peru—were only allowed to attend primary school, and were coerced into working, marrying, or having children in their teens.

A lurking shadow: the tightrope one walks for being a woman, even more if one is a woman from a non-creole or non-white family.

Catholic education is not always as glamorous as it is portrayed. Yes, there is repression of the body and guilt. (Homo)sexuality is contained, but there are also ways to release it. For a young woman who since puberty was aware of her attraction to other girls—and to a lesser degree to boys—the different spaces of female socialization were moments of erotic discovery.

But this was not “erotic” in the crude sense of the term. “Erotic” as “Eros”: an attraction and life force that may at the same time have a sexual component. Eros as an energy that can connect one to their surroundings, with the visible but also with the invisible; with the past, the present, and beyond. Eros as ecstasy. And ecstasy as a state of consciousness that was explored by mystics, poets, and nuns. A tradition of nuns who brought Eros and ecstasy into their works: Hildegard von Bingen, St. Teresa of Avila, and Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

To embrace this tradition and accept the relationship between Eros, ecstasy and feminine spaces is to read the modes of interaction among girls with new eyes. It reinterprets the spaces that comprise Catholic girls’ schools and their “girls’ culture.” Everything is resignified: the school and spiritual retreats—with the cracks that escape the adult gaze—, theatrical plays, parties, and strolling through shopping malls. Parallel spaces of interaction, such as forums and private messages on the Internet, also take on new meaning.

“ÉXTASIS 2000” (2023) by Fiorella Larrea. Instagram: @fiovlt

These readings are only possible thanks to the advance of feminism and the LGBTQ+ movements, and the technological, economic, and social context in the 1990s.

My childhood, influenced by the TV screen, was divided between police and tabloid journalism and cartoons. Quiet Sunday nights with reports about the arrest of prostitutes and “transvestites,” campaigns against AIDS, and news about children addicted to terokal in downtown Lima. And afternoons of anime after school. Animes despite their target audience—most of the time, a female or male adolescent audience—, had the quality of being consumed by everyone: children, young people, and adults. Some of these series even presented topics such as homosexuality and lesbianism openly, questioned gender binarism, highlighted female friendships, and showed us that it was possible for boys, and especially girls, to be heroes.

Television was, therefore, one of our first spaces of socialization and formation of affection. At the same time, a parallel event was taking place: the emergence of a LGBTQ+ literature in Peru. Not only was sexual diversity in adulthood explored, but it also began to reflect on sexuality in childhood and adolescence. Correspondingly, some authors began to reflect on adolescence and middle-class female youth. In these accounts of feminine spaces, one could see the growth of female protagonism together with moments of female intimacy and lesbianism.

Laura Riesco in the novel Ximena at the Crossroads (1994) presents us with the common reception of intimacy between women of different generations: Ximena, the novel’s protagonist, and her mother. While the former interprets the lesbian relationship between her aunt Alejandra and Gretchen as that of a tender friendship in which escapades and cuddling in one another’s bed are a moment of closeness and intimacy, the mother sees physical contact as a threat. For her, lesbianism challenges all previous interaction with other women; she even questions the intimacy and closeness she had with her cousin Alejandra.

Likewise, authors Mariella Sala and Doris Moromisato portray the female, adolescent world. Sala, as an expert narrator in writing female adolescent worlds has in her book Desde el exilio (2019) the short story “Desde mi cielo” (“From my Sky”), originally published in the anthology A flor de piel. Cuentos y ensayos sobre erotismo en el Perú (1993) (‘A flor de piel’. Stories and essays on eroticism in Peru). In that story she narrates the friendship between two girls who, at a sleepover, have their first sexual encounter. In the same 1993 book, Moromisato publishes the story “La misteriosa metáfora de tu cuerpo” (“The mysterious metaphor of your body”), where she describes a teenage girl who studies at a girls’ school and pours the desire she feels for her best friend into writing. Both are stories that represent the indeterminacy of female and adolescent friendships and both are set in closed spaces: the school and the home. It is these closed spaces which define “girls’ culture” in Lima; my “girls’ culture.”

These narratives are, perhaps, a response to the Peruvian youth literature of the 1960s, which presents male homosocial spaces. This, combined with the feminist and LGBTQ+ movements that emerged in Peru in the 1980s and consolidated in the 1990s, created the conditions for the flourishing of LGBTQ+ literature of the subsequent decades.

The 90s is a decade in which a boom in LGBTQ+ literature and a reflection on female childhood and adolescence emerged. Generally, this literature was from an adult perspective, looking back upon female youth. It is also a time when the crisis in Peru seemed to have come to an end after the capture of Abimael Guzman—founder and head of the terrorist group Sendero Luminoso or Shining Path—the “fall” of the Movimiento Revolucionario Túpac Amaru (MRTA) (Tupac Amaru Revolutionary Movement) and the implementation of neoliberal policies. In this context, Lima’s middle and upper classes, with their particular myopia, thought that we had finally achieved stability.

In addition to the usual privileged groups, “mestizos” and whites, new political, social, and economic actors appeared: the Tusanes and Nikkei, descendants of Chinese and Japanese, respectively. These “model minorities” would be opposed in Lima’s imaginary to the indigenous population and migrants, who was related to the “backwardness and violence” in the country. Similarly, the same imaginary would encompass both communities under the label of “chinos” and incarnate them in the figures of the Tusán businessman Erasmo Wong and the Nikkei president Alberto Fujimori.

Thus, being “chino” in Peru in the 1990s and 2000s “seemed not bad.” Already Celia Wu in her book Entre dos mundos: Una infancia chino-peruana (2013) (Between Two Worlds: A Chinese-Peruvian Childhood) speaks of the progressive “incorporation” and gentrification of the Tusanes through Catholic and higher education, and Luis Rocca Torres in Los desterrados: La comunidad japonesa en el Perú y la Segunda Guerra Mundial (2022) (The Exiles. The Japanese Community in Peru and the Second World War) points out the creation of educational, entertainment and media spaces by the Nikkei community after World War II. But despite this supposed “assimilation” and participation, being “chino” meant and still means being the object of ridicule and prejudice, regardless of one’s economic status or cultural capital.

The nineties were a decade where access to the economy was coupled with globalization and the emergence of new technologies. A childhood marked by computers, video games, television series, anime, music, and cartoons.

Sorry, but books and literature would come later ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

In this decade feminist efforts were also swallowed up by Fujimori’s government and a Ministry of Women was created. A progressive facade for a government that was anything but feminist: forced sterilizations, rapes, disappearances, and murders of children, indigenous women, and anyone who objected.

And what about the LGBTQ+ communities? The fear of AIDS had been dragging on for the past decade and there were policies designed to contain affected trans-women and prostitutes. These groups of people were a different risk sector than the one pointed out by the medical discourse: middle- and upper-class homosexuals. To the AIDS crisis in the 1980s and the persecution and raids by the police, there were additionally the attacks perpetrated by Shining Path, followed by sensationalism and misinformation in the press. Therefore, in the context of this general crisis and the bombardment of information on homosexuality would lead to an editorial interest in LBGTQ+ issues and also to activism in Lima, such as the sit-in in Miraflores in June 1996.

Being, then, a middle-class Tusán and educated girl from Lima in the nineties meant growing up in the context of social ascent for Asians descendants and in a period governed by globalization, technologization, and neoliberalism. It also means remembering two other shadows that haunt us: the unresolved wounds of the internal armed conflict and the awareness of a potential (homo)sexuality. Regarding the former, the marches and assassinations by Dina Boluarte’s government reflect our failure and inability to examine the problems that provoked the crisis of the eighties. The latter is about a desire that was silenced, but which always finds loopholes through which to emerge.

Our (homo)sexuality in latency. In play, an opportunity or excuse to explore: lifting skirts, touching the breast, sitting on a friend’s legs, pretending to be married/have wives, bringing the face dangerously close, blowing gently or caressing the ear, passing the pencil or pen on a friend’s arm… All ways to explore the body and compare. Perhaps we were rebelling against shame and asserting our body in response to a society shamed the possession of a body. Perhaps it was a way to assert power over those who felt insecure in their skin.

A memory: the last spiritual retreat of our prom. A girl in front of the campfire, staring blankly. What was she thinking about? She liked poetry. She wrote poetry just as I wrote narrative. And in that spring I felt the warmth of her tears on my neck and the eternity of her embrace. A sense of peace and infinity like the one I felt when I listened to mass or prayed in the chapel. The voice of the priest, the chants and prayers repeated like mantras… Reaching other planes of consciousness, between being and non-being.

Feminine and Catholic education seems to be a deformed asceticism. It ranges from a modest and sober life of spiritual perfection to a spiritual salvation through Marianism, surrender, abnegation, chastity, and self-denial.

But female education, when all is said and done, cannot escape its homosocial component. Such a homosocialization is not exclusive to female and Catholic education, but is explored in other regions and literary traditions such as the French Claudine à l’école (1900), the German Mädchen in Uniform (1931), the English Olivia (1949) and the Japanese Hana Monogatari (1916-1924).

Writing is not just a privilege. To continue to write is a living testimony of those who have survived and are willing to risk everything. Survivors know the fragility of memory.

Writing was the way for these witnesses to explore their bodies and reflect on their past. Literature is accordingly a form of reappropriation and liberation. Some recurrent themes in these works: the use of fiction to hide a name; the girls’ school as a space to question the norms that will mold the young woman into an adult; literature and education as vehicles for the growth of the adolescent; and theater and dance as events that foreground the artificiality of roles.

But why the insistence on roles?

Plays at a girls’ school always had the same outcome: many shied away from male roles, leaving a handful of us to take them. There were also roles in folk dance classes. Dance and theater: measured movements where art and stage discipline the body.

Bodies that play roles on stage.

Calderón de la Barca exposed how life is theater and we are mere actors… But in a female homosocial space, those who watch and those who act can reinterpret these roles in a queer or non-binary key. The adolescent performs a masculine role. Or rather, a body that normally performs a feminine role momentarily performs a masculine role. Or even more complex: it is a body that tries to perform masculinity in a context where femininity is forced upon it. It is on stage where it finds the space to perform the yearned-for masculinity.

Off stage is where the roles dissolve. Parties, as environments that originate in ritual space—where music, drink and dance come together—are suitable for finding freedom.

Dance allows one to be aware of one’s body and the bodies of those around us. With dance and music, the body is diluted in an ecstasy of synesthesia. Music, coupled with dance, leads to other states of consciousness. Music is also a place for the exploration of female sexuality. A list of artists who managed to attract fangirls: Franz Liszt, Elvis Presley, The Beatles, One Direction, BTS. Female fans experienced manic states when watching their artists, but this is never a guarantee of their heterosexuality.

Fourteen years old: the first parties among friends. Our bodies uninhibited with our first drinks. And sometimes not even with drinks… Just letting the body go regardless of hunger, thirst, or exhaustion.

With music, dance, and fatigue, consciousness turns ethereal and it is possible to become all. In music and dance the sacred and the profane desires meet. In music and dance, ecstasy turns desire into the sacred.

Parties were a privileged space for heterosexual encounters. And yet they easily became a place that escapes all categories for those who have a queer gaze. We see, then, how it is resignified.

- “Gozo” (2021) by Fátima Sarmiento. Instagram: @faunacollage

- “Afrodita” (2021) by Fátima Sarmiento. Instagram: @faunacollage

Another space of heterosexual interaction that is reterritorialized by queerness is the shopping mall. This is no longer the “safe place,” between the street and the enclosed, where one meets boys or where one builds early friendships. The mall, despite being a place of consumption, is also a place for socializing with other girls, and it is an area—along with the home—that allows us to explore our personalities outside of the rigor and expectations of school.

Some dates with men and women during adulthood: home visits and walks in the same shopping malls visited during adolescence. Intimate friendships blur the line between their platonic component and the first romantic and sexual encounters during adulthood?

The queer adolescent also appropriates the Internet. Moreover, she takes it as a natural place for the exploration of desire and sexuality. It is a place of socialization without surveillance. To the first voyeuristic—and, why not, polyamorous—encounters with the consumption of dōjinshi, hentai, fanfiction, yaoi and yuri—self-published Japanese works, Japanese pornography, fan-made derivative fiction, and Japanese gay and lesbian manga or comics, where the consumer observes the romantic or sexual outcome of the characters—we add the anonymity of our interactions in forums and role-playing games. For some, it meant the opportunity to fall in love with a friend who was only known virtually. The Internet is, in this way, a queer place where geographical boundaries dissolve and where we transgress what is expected of our gender and imposed sexuality.

Talking about the past may be an act of nostalgia. Isn’t writing about and studying “girls’ culture” a way to regain control of my adolescence? But nostalgia only comes in the face of a sense of loss. And “girls’ culture” doesn’t end with adolescence.

Theory states that such culture is centered on the forms of production, exchange, and consumption of that stage of life. But when I see my apeu—cantonese for “grandmother”—or mi madre with her friends, I see how they embody characteristics of their “girls’ culture.” Their referents, vocabulary, and forms of interaction sometimes resemble and sometimes differ from my own culture.

My tía Violeta and the joy she had when she showed me her collection of The Beatles. My apeu and her anecdotes about her sisters and her classmates: reading comic books, taking bus rides with her mother, pranks on teachers, matinee outings, meeting boys—and the news of some teenage pregnancies. And mi madre, the pop-subte and her desire for liberation in the 80s and 90s.

So, if it is possible to speak of a “girls’ culture” beyond adolescence, there could be one in adulthood as well. In In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (2005) Jack Halberstam points out that the experience of coming out is tantamount to living a second adolescence. Therefore, we can speak of a queer, trans, lesbian and adult “girls’ culture.”

These spaces, as Halberstam himself has identified, are perceived by society as “non-productive” because the subject does not conform to heteronormative activity. This is how sexual dissidence is conceived as “immature.”

In this way, “girls’ culture” defies linear time by reactivating past stages of life much later. Not only this, but it also challenges linear heteronormativity when we refer to spaces of LGBTQ+ socialization organized by trans and feminist collectives, such as the self-managed fairs and queer parties in downtown Lima, where parallel economic and affective circuits are established.

Conversation with an ex: “Are there places for anonymous sexual encounters between women?”

Theory studies the act of cruising, and parks, public baths, saunas, or dark rooms as spaces for male homosexual encounter. But there are those who point out that there is no equivalent in lesbian culture. This is because it is the product of an education based on modesty, the assimilation of monogamy and romantic love.

Parties and private meetings. The music at full blast and between games and drinks…

Are we still locked up?

The “girls’ culture” as I know it, between school and physical and virtual spaces, is queer. Or rather, some of us make these spaces queer. It is a culture that prepares us for heterosexuality and motherhood, but also one in which some of us find our first lesbian spaces of socialization and friendships and loves that transcend any definition. This ecstasy is achieved both in carnal encounters and in the mere gaze and touch.

Already in the 19th and part of the 20th century there were women who preferred to refer to their partner(s) as “girlfriends.” Likewise, “girls’ culture” and queer people prefer to call their partners or lovers in terms of friendship. Perhaps we are inserting ourselves into passionate friendships escape all categories. Such a strategy was adopted by some women at the turn of the century to escape the gaze that pathologized lesbianism.

More than fear, it may be that the desire to escape categorization and to accept the difficulty of naming corresponds to an alternative way of seeing the body, identity, and sexuality. On the one hand, naming implicitly utilizes categories invented and imposed by others. On the other hand, not naming is to embrace the blurriness of boundaries and categories. It is to transcend and go beyond them. The trick is to synchronize between one and the other, to “make them dance” and “to dance with them.”

Today, with what appears to be a return to political and religious conservatism in Lima with the election of Rafael López Aliaga to the mayoralty of Lima, and with the emergence of the extreme right-wing collective La Resistencia, it becomes even more important to rescue the “girls’ culture” of Catholic and feminine schools and to recognize its queer potential.

Ecstasy,—as a state of consciousness that can be achieved through normative practices such as prayer, mass, and chanting—invites becoming. And becoming, with an inherent element of spirituality, blurs boundaries and establishes connections that seem impossible for those who cling to common sense.

“Tonta Heroína” (2018) por Ro aka Estado de Limbo. Twitter: @estadodelimbo

Entre lo sacro y lo profano

Una visión sobre la cultura de chicas limeña

Por Alexandra Arana Blas

Mi infancia y adolescencia en Perú fueron definidas por la escuela en la primera década del 2000.

Hay una experiencia tan limeña en los colegios y un hermetismo y celo que los caracteriza. Había una costumbre de privilegiar una educación en los colegios católicos femeninos o masculinos. También, claro, existen en nuestro panorama limeño los colegios públicos y extranjeros. Incluso en nuestra literatura están retratados los colegios militares, como el Leoncio Prado en La ciudad y los perros (1963). Pero probablemente, hasta los primeros años del 2000, primaba una educación católica, conservadora y homosocial.

Crecí en un colegio católico y femenino. Tercera generación en colegio femenino; segunda en colegio católico y femenino. Es un privilegio estudiar cuando se es consciente de que hasta hace tres generaciones se obligaron a mis bisabuelas maternas—una de familia terrateniente en la sierra, y otra, primera generación de migrantes chinos nacida en el Perú—a solo tener primaria, trabajar, casarse o tener hijos en la adolescencia.

Una sombra que acecha: la cuerda floja sobre la cual se camina por ser mujer, más aún si se es mujer de familia no criolla ni blanca.

La educación católica no es siempre como la pintan. Sí, hay represión del cuerpo y culpa. Hay una (homo)sexualidad contenida, pero también hay formas de liberarla. Para una joven que desde la pubertad era consciente de su atracción por otras chicas—y en menor nivel por chicos—, los diferentes espacios de socialización femenina fueron momentos de descubrimiento erótico.

No “erótico” en el sentido burdo del término. “Erótico” como “Eros”: atracción y fuerza vital que a la vez puede tener un componente sexual. El Eros como energía que puede conectar a uno con aquello que lo rodea, con lo visible pero también con lo invisible; con el pasado, el presente y más allá. El Eros como éxtasis. Y el éxtasis como estado de la consciencia que fue explorado por místicos, poetas y monjas. Una tradición de religiosas que llevaron el Eros y el éxtasis a sus obras: Hildegard von Bingen, Santa Teresa de Ávila y Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz.

Abrazar esta tradición y aceptar la relación entre Eros, éxtasis y espacios femeninos es leer con nuevos ojos los modos de interacción y los espacios que caracterizan a las escuelas católicas femeninas y su “cultura de chicas”. Todo se resignifica: el colegio y los retiros espirituales—con las hendiduras que escapan de la mirada adulta—, las obras teatrales, las fiestas y las salidas a los centros comerciales. Toman un nuevo significado también espacios de interacción paralelos, como los foros y mensajes privados por Internet.

“ÉXTASIS 2000” (2023) por Fiorella Larrea. Instagram: @fiovlt

Estas lecturas solo son posibles gracias al avance del feminismo y los movimientos LGBTQ+, y el contexto tecnológico, económico y social en los 90.

Mi niñez, influenciada por la pantalla del televisor, estuvo dividida entre un periodismo policial y amarillista, y los dibujos animados. Quietas noches de domingo con reportes sobre la captura de prostitutas y “travestis”, campañas contra el sida y noticias sobre los niños adictos al terokal en el Centro de Lima. Y tardes de anime regresando del colegio. El anime o dibujos animados japoneses, a pesar de tener demografías, tenía la cualidad de que un título, dirigido originalmente a un público femenino o masculino adolescente, podía ser consumido por todos: niños, jóvenes o adultos. Algunas de estas series incluso presentaban sin tapujos temas como la homosexualidad y el lesbianismo, cuestionaban el binarismo de género, resaltaban las amistades femeninas y nos mostraron que era posible para los niños, y en especial las niñas, ser héroes.

La televisión fue, así, uno de nuestros primeros espacios de socialización y formación de afectos. A lo señalado, ocurría un evento paralelo: el surgimiento de una literatura LGBTQ+ en el Perú. En ella, no solo se exploró la diversidad sexual en la adultez, sino también se comenzó a reflexionar sobre la sexualidad en la niñez y la adolescencia. Es así como algunas autoras comenzaron a reflexionar sobre la adolescencia y juventud femenina clasemediera. A estos recuentos de espacios femeninos donde vemos el crecimiento de las protagonistas, se incluyen momentos de intimidad femenina y lesbianismo.

Laura Riesco en la novela Ximena de dos caminos (1994) nos presenta la recepción de la intimidad entre mujeres de distintas generaciones: Ximena, protagonista de la novela, y su madre. Mientras que la primera interpreta la relación lésbica entre su tía Alejandra y Gretchen como la de una tierna amistad, donde las escapadas y los abrazos en la cama de la otra son un momento de cercanía e intimidad, la madre ve el contacto físico como una amenaza. Para ella, el lesbianismo interpela toda interacción previa con otras mujeres; incluso cuestiona la intimidad y cercanía que tuvo con su prima Alejandra.

De igual manera se aventuran a retratar los mundos femeninos y adolescentes las autoras Mariella Sala y Doris Moromisato. Sala, como narradora experta en la escritura de mundos adolescentes femeninos tiene en su libro Desde el exilio (2019) el cuento “Desde mi cielo”, publicado originalmente en la antología A flor de piel. Cuentos y ensayos sobre erotismo en el Perú (1993). En dicho cuento narra la amistad entre dos chicas que, en una pijamada, tienen su primer encuentro sexual. En el mismo libro de 1993, Moromisato publica el cuento “La misteriosa metáfora de tu cuerpo”, donde describe a una adolescente que estudia en un colegio femenino y vuelca en la escritura el deseo que siente por su mejor amiga. Ambos son cuentos que representan la indeterminación de las amistades femeninas y adolescentes, y se ubican en espacios cerrados: el colegio y el hogar. Los espacios cerrados como aquello que define la “cultura de chicas” en Lima, mi “cultura de chicas”.

Estas narrativas son, quizás, una respuesta a la literatura peruana juvenil de los años sesenta, la cual presenta espacios homosociales masculinos. Y esta réplica sería producto de los movimientos feministas y LGBTQ+ que surgen en el Perú de los años 80 y se consolidan en los años 90.

Los 90 son una década en la que surge un boom en la literatura LGBTQ+ y una reflexión, desde una mirada adulta, sobre las infancias y adolescencias femeninas. Es también una época donde la crisis en el Perú parecía haber llegado a su fin luego de la captura de Abimael Guzmán—fundador y cabeza del grupo terrorista Sendero Luminoso—, la “caída” del Movimiento Revolucionario Tupac Amaru (MRTA) y la aplicación de políticas neoliberales. En este contexto, las clases medias y altas limeñas, con la miopía que hasta ahora las caracteriza, pensaron que por fin logramos la estabilidad.

Asimismo, a los grupos privilegiados de siempre, “mestizos” y blancos, había que sumar nuevos actores políticos, sociales y económicos: los tusanes y nikkeis, descendientes de chinos y japoneses respectivamente. Estas “minorías modelo” estarían contrapuestas en el imaginario limeño a la población y migración indígena, la cual era relacionada con el “atraso y violencia” en el país. Y de igual manera, el mismo imaginario englobaría a ambas comunidades bajo la etiqueta de “chinos” y las encarnaría en las figuras del empresario tusán Erasmo Wong y el presidente nikkei Alberto Fujimori.

Así, ser “chino” en el Perú de los 90 y 2000 “parecía no estar tan mal”. Ya Celia Wu en su libro Entre dos mundos: Una infancia chino-peruana (2013) habla de la progresiva “incorporación” y aburguesamiento de los tusanes a través de la educación católica y superior, y Luis Rocca Torres en Los desterrados: La comunidad japonesa en el Perú y la Segunda Guerra Mundial (2022) señala la creación de espacios educativos, de entretenimiento y medios de comunicación por parte de la comunidad nikkei luego de la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Pero a pesar de esta supuesta “asimilación” y participación, ser “chino” significó y significa aún ser objeto de burlas y prejuicio, sin importar el nivel económico o capital cultural que se tenga.

Los noventa: década donde el acceso a la economía se unió a la globalización y la entrada de algunas tecnologías. Una infancia marcada por las computadoras, videojuegos, series, anime, música y dibujos animados.

Sorry, pero los libros y la literatura vendrían después ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

En esta década también las luchas feministas fueron deglutidas por el gobierno de Fujimori y se creó un Ministerio de la Mujer. Una fachada progresista para un gobierno nada feminista: esterilizaciones forzadas, violaciones, desapariciones y asesinatos contra niños, mujeres indígenas y cualquier persona que se opusiera.

¿Y sobre las comunidades LGBTQ+? Se arrastraba desde la década pasada el miedo por el sida y existían políticas de contención que afectaban a mujeres trans y prostitutas, un sector de riesgo diferente al que señalaba el discurso médico: los homosexuales de clases medias y altas. A esta crisis del sida en los ochenta y la persecución y redadas por parte de la policía, hay que sumarle los ataques que perpetró Sendero Luminoso, el sensacionalismo y desinformación por parte de la prensa. Por tanto, el contexto de crisis general y el bombardeo de información sobre la homosexualidad llevaría en los noventa, desde el lado de la literatura, a un interés editorial por este tema; y desde el activismo, a algunas movilizaciones LGBTQ+ en Lima, como el plantón en Miraflores en junio de 1996.

Ser, entonces, una niña tusán clasemediera limeña de los noventa significa haber crecido en un contexto de ascenso social para los asiático descendientes, y en una etapa regida por la globalización, tecnologización y el neoliberalismo. También implica tener la mirada atenta sobre otras dos sombras que nos acechan: las heridas irresueltas del conflicto armado interno y la consciencia de una (homo)sexualidad en potencia. Sobre la primera, las marchas y los asesinatos por parte del gobierno de Dina Boluarte son un reflejo de nuestro fracaso e incapacidad de examinar los problemas que provocaron la crisis de los ochenta. La segunda se trata de un deseo que fue silenciado, pero que siempre encuentra resquicios por los cuales transitar.

La (homo)sexualidad en potencia: una oportunidad que algunas se dieron en el colegio para explorar. En el juego, una excusa, una forma de tantear: levantar las faldas, tocar el pecho, sentarse sobre las piernas de la amiga, tomar esposas, acercar peligrosamente el rostro, soplar suavemente o acariciar la oreja, pasar el lápiz o el lapicero en el brazo de la amiga… Formas de explorar el cuerpo y comparar. Quizás, nos rebelábamos contra la vergüenza y afirmábamos nuestro cuerpo en respuesta a una sociedad que nos lo negaba. Quizás una forma de afirmar el poder sobre aquellas que se sentían inseguras en su piel.

Un recuerdo: el último retiro de promoción. Una chica frente a la fogata, con la mirada perdida. ¿En qué pensaba? Le gustaba la poesía. Escribía poesía, como yo narrativa. Y en esa primavera, el calor de sus lágrimas en mi cuello y la eternidad de su abrazo. Una sensación de paz e infinito como la que sentía cuando escuchaba la misa u oraba en la capilla. La voz del sacerdote, los cantos y las oraciones repetidos cual mantras… Alcanzar otros planos de consciencia, entre el estar y no estar.

La educación femenina y católica pareciera ser un ascetismo deformado: de una perfección espiritual a través de una vida modesta y sobria, a una salvación espiritual a través del marianismo, la entrega, la abnegación, la castidad y el negarse a sí mismo.

Pero la educación femenina, al fin y al cabo, no puede escapar de su componente homosocial. Una homosocialización que no es exclusiva de la educación femenina y católica, sino que se explora en otras regiones y tradiciones literarias: la francesa Claudine à l’école (1900), la alemana Mädchen in Uniform (1931), la inglesa Olivia (1949) y la japonesa Hana Monogatari (1916-1924).

Escribir no es solo un privilegio. Continuar con la escritura es testimonio de quien ha sobrevivido y arriesga todo porque conoce la fragilidad de la memoria.

La escritura fue el medio para estas escritoras para explorar su cuerpo y reflexionar sobre su pasado. La literatura es, así, una forma de reapropiación y liberación. Algunos temas se repiten en estas obras: el uso de la ficción para ocultar el nombre; el colegio femenino como espacio para cuestionar las normas que insertarán a la joven en la vida adulta; la literatura y la educación como vehículos para el crecimiento de la adolescente; y el teatro y la danza como eventos que colocan en primer plano la artificialidad de los roles.

¿Por qué la insistencia en los roles?

Las obras de teatro en un colegio femenino tenían el mismo desenlace: algunas rehuían a los papeles masculinos, lo cual dejaba a un puñado que debíamos tomarlos. También en las clases de danza folclórica había roles. El teatro y la danza: movimientos medidos donde son el arte y el escenario los que disciplinan al cuerpo.

Cuerpos que cumplen roles en un escenario.

Ya Calderón de la Barca había expuesto cómo la vida es teatro y nosotros meros actores… Pero en un espacio homosocial femenino, tanto quien mira como quien actúa puede reinterpretar estos roles en una clave queer o no-binaria. La adolescente performa un rol masculino. O mejor dicho, es un cuerpo que performa un rol femenino que momentáneamente performa un rol masculino. O más complejo aún: es un cuerpo que intenta performar una masculinidad en un contexto donde se le obliga a la feminidad; y en el escenario es donde encuentra el espacio para performar la ansiada masculinidad.

Fuera de la escenografía es donde se disuelven los roles. Las fiestas, como ambientes que tienen por origen el espacio ritual—donde la música, bebida y danza se juntan—, son adecuadas para encontrar la libertad.

La danza permite a uno ser consciente de su cuerpo y del cuerpo de quienes lo rodean. Con la danza y la música, el cuerpo se diluye en un éxtasis de sinestesia. La música, unida a la danza, lleva a otros estados de consciencia. La música también ha sido un lugar de exploración para la sexualidad femenina. Una lista de artistas que lograron atraer a fanáticas o fangirls: Franz Liszt, Elvis Presley, The Beatles, One Direction, BTS. De ellas se ha hablado de los estados maníacos que atravesaban al ver a sus artistas, pero esto nunca es garantía de su heterosexualidad.

Catorce años: las primeras fiestas entre amigas. Nuestros cuerpos desinhibidos con los primeros tragos. Y a veces ni tragos… Solo dejar el cuerpo llevar sin importar el hambre, la sed o el cansancio.

Con la música, la danza y la fatiga, la consciencia se torna ligera y es posible ser toda. En la música y la danza se encuentran lo sacro y los deseos profanos. En la música y la danza el éxtasis convierte el deseo en sagrado.

Las fiestas, como espacio privilegiado para el encuentro heterosexual, se convierten así en un lugar que escapa de toda categoría para quien posee una mirada queer. Vemos, entonces, cómo se resignifica.

- “Gozo” (2021) by Fátima Sarmiento. Instagram: @faunacollage

- “Afrodita” (2021) by Fátima Sarmiento. Instagram: @faunacollage

Otro espacio de interacción heterosexual que se reterritorializa es el centro comercial. Este no es más el “lugar seguro”, entre la calle y lo cerrado, donde uno se encuentra con chicos o donde se construye las primeras amistades. El centro comercial, a pesar de ser un lugar de consumo, también lo es de socialización con otras chicas, y es una zona—junto al hogar—que permite conocer cómo son fuera de la escuela.

Algunas citas con chicos y chicas durante la adultez: visitas en las casas y paseos en los mismos centros comerciales recorridos durante la adolescencia. ¿Acaso las amistades íntimas no tienen un componente platónico que se acerca a nuestros primeros encuentros románticos y sexuales durante la adultez?

También la adolescente queer se apropia del Internet. Es más, lo toma como lugar natural para la exploración de su deseo y sexualidad, pues es un lugar de socialización sin vigilancia. A los primeros encuentros voyeristas—y, por qué, no poliamorosos—con el consumo de dōjinshi, hentai, fanfiction, yaoi y yuri—obras japonesas autopublicadas, pornografía japonesa, ficción derivada hecha por fans, y manga o cómic japonés homosexual y lésbico, donde quien consume es testigo del desenlace romántico o sexual de los personajes—, se le suma el anonimato de nuestras interacciones en foros y los juegos de rol. Para algunas, significó la oportunidad de enamorarse de alguna amiga que solo conocían en la virtualidad. El Internet es, de esta manera, un lugar queer donde se disuelven las fronteras geográficas, y donde transgredimos lo que se espera de nuestro género e impuesta sexualidad.

Hablar del pasado podría estar relacionado con la nostalgia. ¿Acaso escribir y estudiar la “cultura de chicas” no es una forma de recuperar el control de mi adolescencia? Pero la nostalgia solo viene ante la sensación de pérdida. Y la “cultura de chicas” no acaba con la adolescencia.

Sí, la teoría afirma que dicha cultura se centra en las formas de producción, intercambio y consumo de esa etapa. Pero cuando veo a mi apeu—cantonés para “abuela”—o mi madre con sus amigas, veo cómo en ellas se activan características de la “cultura de chicas”: referentes, vocabulario y formas de interacción que a veces se parecen y otras difieren de mi cultura.

Mi tía Violeta y su alegría cuando me mostraba su colección de discos de The Beatles. Mi apeu y las anécdotas con sus hermanas y sus compañeras de promoción: leer historietas, los paseos en bus con su mamá, las travesuras a las profesoras, las salidas para la matiné, conocer chicos—y la noticia de algunos embarazos adolescentes—. Mi madre, lo pop-subte y su deseo de liberación en los 80 y 90.

Por tanto, si es posible hablar de una “cultura de chicas” más allá de la adolescencia, podría existir también una en la adultez. En In a Queer Time and Place: Transgender Bodies, Subcultural Lives (2005) Jack Halberstam señala que la experiencia de salir del clóset equivale a vivir una segunda adolescencia. Entonces, podemos hablar de una “cultura de chicas” queer, trans, lésbica y en la adultez.

Estos espacios, como el mismo Halberstam ha identificado, son percibidos por la sociedad como “no productivos”, pues no insertan al sujeto en la heteronorma. Es así como se concibe a las disidencias sexuales como “inmaduras”.

De esta manera, la “cultura de chicas” no solo es queer porque desafía el tiempo lineal al poder ser reactivada sin importar los años que pasen. También lo es cuando nos referimos a espacios de socialización LGBTQ+ organizados por colectivos trans y feministas, como las ferias autogestivas y las fiestas queer del Centro de Lima, donde se establecen circuitos paralelos económicos y afectivos.

Conversación con una ex: “¿Acaso hay lugares de encuentro anónimo y sexual entre mujeres?”

En la teoría se habla del cruising, los parques, los baños públicos, los saunas o los cuartos oscuros para los homosexuales, pero hay quienes señalan que no existe un equivalente en la cultura lésbica, producto de una educación basada en el pudor, la asimilación de la monogamia y el amor romántico.

Fiestas y reuniones privadas. La música a tope y entre juegos y tragos…

¿Seguimos estando encerradas?

La “cultura de chicas”, tal y como la conozco, entre la escuela y los espacios físicos y virtuales, es queer. O mejor dicho, algunas hacemos de estos espacios queer. Es una cultura que nos prepara para la heterosexualidad y la maternidad, pero donde algunas encontramos nuestros primeros espacios de socialización lésbicos, en amistades y amores que trascienden toda definición: el éxtasis que se alcanza tanto en los encuentros carnales como en la sola mirada y el tacto.

Ya en el siglo XIX y parte del XX había mujeres que preferían referirse a su(s) compañera(s) como “amigas”. Así mismo, la “cultura de chicas” y las personas queer prefieren llamar a sus parejas o amantes en términos de amistad. Quizás nos insertamos en amistades apasionadas que precisan escapar de toda categoría, estrategia que adoptaron algunas mujeres de inicios de siglo para escapar de la mirada médica.

Más que miedo, puede ser que el deseo de no categorizar y aceptar la dificultad de nombrar responda a una forma alternativa de ver el cuerpo, la identidad y la sexualidad. Por un lado, el nombrar es una respuesta a las categorías impuestas por los otros. Por el otro, el no nombrar es abrazar lo difuso en los límites y las categorías; es trascender e ir más allá. El truco es sincronizar entre uno y el otro, “hacerlos bailar” y “bailar con ellos”.

Hoy por hoy, con lo que parece ser un retorno al conservadurismo político y religioso en Lima, a través de la elección de Rafael López Aliaga a la alcaldía de Lima, y el surgimiento del colectivo de extrema derecha La Resistencia, se torna aún más importante el rescatar la “cultura de chicas” de las escuelas católicas y femeninas y reconocer su potencial queer.

El éxtasis, como estado de consciencia al cual se llega por las prácticas normativas como la oración, la misa y los cantos, invita al devenir. Y el devenir, como elemento inherente a la espiritualidad, difumina los límites y establece conexiones que parecen imposibles para quienes se aferran al sentido común.

“Tonta Heroína” (2018) por Ro aka Estado de Limbo. Twitter: @estadodelimbo

Alexandra Arana Blas is a graduate student at the University of Pittsburgh. She is a fourth generation Tusán on her mother’s side. Her research revolves around the construction of female characters in literature, girls’ culture, LGBTQ+ literature, transpacific studies, fandoms, and otaku culture. Twitter: @Alex_ABlas. Linktree: www.linktr.ee/alex_a.blas

Alexandra Arana Blas es estudiante de posgrado en la Universidad de Pittsburgh. Tusán de cuarta generación por parte materna. Sus investigaciones giran en torno a la construcción de personajes femeninos en la literatura, la cultura de chicas, la literatura LGBTQ+, los estudios transpacíficos, los fandoms y la cultura otaku. Twitter: @Alex_ABlas. Linktree: www.linktr.ee/alex_a.blas

Related Articles

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

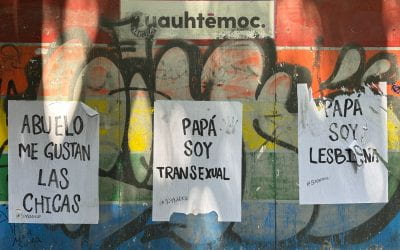

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.

Editor’s Letter

This is a celebratory issue of ReVista. Throughout Latin America, LGBTQ+ anti-discrimination laws have been passed or strengthened.