Calaveritas Literarias

Honoring Queer Latinx Artists

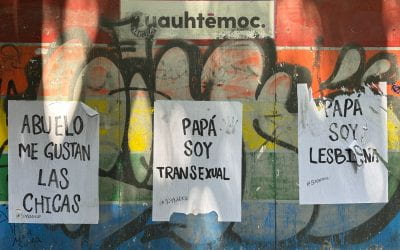

Latine/x identity extends beyond a specific month or celebration. As immigrants away from our home country or first-generation living in a new state, we find self-acceptance in spaces where we can find a sense of belonging and freedom in communicating our culture through contemporary expression. How can we, as queer Latine/x artists, honor our cultural background while seeking to redefine narratives in spaces where our identities are only explored on a surface level?

When I migrated the United States close to ten years ago for a job as a grade school bilingual educator, I found that despite sharing a language with the students, I was navigating a new culture and work environment that seemed to appreciate a style of work that did not align with my upbringing in Mexico. In my past professional experience, I never had to reflect on my cultural background or intersectional identities since most of my colleagues shared an ethnic-racial and sociolinguistic identity. Once in the United States, I started having to answer questions that never seemed to be a determinant in past professional contexts. “Where are you from?” And hearing ongoing simplistic or stereotypic connections to my place of origin.

When I migrated the United States close to ten years ago for a job as a grade school bilingual educator, I found that despite sharing a language with the students, I was navigating a new culture and work environment that seemed to appreciate a style of work that did not align with my upbringing in Mexico. In my past professional experience, I never had to reflect on my cultural background or intersectional identities since most of my colleagues shared an ethnic-racial and sociolinguistic identity. Once in the United States, I started having to answer questions that never seemed to be a determinant in past professional contexts. “Where are you from?” And hearing ongoing simplistic or stereotypic connections to my place of origin.

September 16 came, and a date that had been a commemoration of Mexican Independence and the perfect day to miss school suddenly became the beginning of an intentional month of cultural representation and advocacy. I could recognize the need for more representation and acceptance from members of our social context. However, I was still surprised to see the recognition on an artistic level without demonstrating a genuine interest in knowing and including multiple perspectives outside of those four weeks. As an artist and an educator, I wanted to connect with my first group of students while also resisting a superficial way of representing the richness of our diverse identities. Our classroom became a culturally responsive inquiry, curiosity and creativity space.

As I continued navigating my journey as a Latine/x immigrant living in Texas, I found community in spoken word spaces and places where my mother tongue did not cause anyone to turn heads. I found a comunidad in queer creative spaces across North Texas art collectives. I gained inspiration from BIPOPC (Black, Indigenous, and People of Color) creatives who utilized their identities as strong sources of inspiration and collective healing within a sociopolitical context that would communicate hurtful narratives of entire communities. I started attending spoken word events and open mics, where cultural representation came in the form of intergenerational dialogue and interdisciplinary artmaking that incorporates our cultural roots while accepting change.

In November 2014, during my first year as an educator and living in the United States, I found a meaningful way to connect with my origins through a tradition present in my life growing up back home, Día de Muertos (Day of the Dead). This prehispanic tradition is a celebration of life while honoring our loved ones who have passed away. In Mexico, it is a time of the year to remember our ancestors and the memories that have shaped our personal journeys. We would set an altar or ofrenda at home every year, placing photos of our loved ones, cempasúchil flowers, candles, pan de muerto (bread), sugar skulls, papel picado (paper banners) and more.

During my childhood, we would also set altars or ofrendas in my school, learning more about the contributions of famous leaders who had passed away and who, according to tradition, would come to visit the altar once a year during the Day of the Dead. A ritual that could seem scary to others was a moment of collaboration, joy, and experiential learning for us. Out of all traditions, literary calaveritas were my favorite part of Dia de Muertos. These calaveritas are playful and satirical poems that feature death and the famous Catrina, a character created by José Guadalupe Posada, an artist and journalist, as a social call. They can refer to people who have passed away or are still alive; they are often about politicians or famous artists. There is a specific literary structure, including verses with eight syllables, consonant rhymes, humor, personal characteristics, and an encounter with Death. Many modern poets and community members write in free form, prioritizing creativity and the joy of composing.

I was hosting a poetry and spoken word club at my school and decided to teach my students, mostly immigrant-origin youth, how to write their own poems. We learned about the significance of this celebration in Mexico and across Latin American countries, the components of the ofrenda, and how to honor our loved ones through artistic expression in the form of satirical poetry with a character who personalized death.

I was hosting a poetry and spoken word club at my school and decided to teach my students, mostly immigrant-origin youth, how to write their own poems. We learned about the significance of this celebration in Mexico and across Latin American countries, the components of the ofrenda, and how to honor our loved ones through artistic expression in the form of satirical poetry with a character who personalized death.

Poetry was a personal safe outlet when growing up on the border of Juárez, Chihuahua-El Paso, Texas, and a companion in moments of uncertainty, self-reflection, and uncontrollable change. And as a Latina who was scared to explore and express her diverse identities, I found refuge in the art of queer Latinx artists who allowed me to remain close to my roots while finding ways to combat a patriarchal system that taught us to deny our authentic selves. Whether through paintings, music or the courage to dress outside the norm, I admired their audacity and courage to remain faithful to their creative process among external expectations. Now, as a Latina artist who has been a migrant for most of her adult life, I can recognize the value of learning more about artists who have paved the way for us and creating art that addresses complex topics through loving resistance and self-compassion. Here are three calaveritas (poems) dedicated to three queer Latinx artists who have influenced my work:

El Divo de Juárez

Here comes captivating Juanga,

A singer with mucha alma.

He grew up in the Bordertown,

A city in search of calma.

One day, the Parca came for him,

And got him off stage forever.

But in the end, she did not know

that Juan Gabriel was clever.

He left parts of his soul in songs,

Melodies that connect with our souls.

He wrote lyrics about nightclubs,

Mountains, and cosas que se ven

y no se preguntan, don’t ask!

He wore stars and lentejuelas

To express his unique beauty

And moved his hips to the rhythm

from Mariachi to Bunbury.

La Muerte never leaves his side,

With a personal concert live.

Famous Frida

This poem is for Friducha,

A famously known artista.

She painted many self-portraits,

Filled with bold colors and symbols.

She loved and married her Diego,

The opposite of sociego.

He was everything but calmness,

All inspiration and anger.

Frida and her unibrow live

In the popular art, we give.

One day la Muerte came for her,

And Frida then said ¡ay mujer!

They left skipping and holding hands,

Following an embroidered path.

She loved animals and culture,

But she loved Mexico the most.

Kahlo was her paternal name.

On the other side, there is fame.

Calaverita a Chavela Vargas

Ahí viene la Chavela,

con pantalón sin cadenas,

cante y cante hacia el cielo,

llore y llore como el infierno.

La bebida fue su perdición,

aunque con José Alfredo se rio.

Chavelita pasó tanto tiempo en el olvido,

que La Parca se convirtió en su amigo.

La tica ya se va,

la tica ya llegó,

la tica se volvió más mexicana que el frijol.

La huesuda llegó a tocar su puerta,

pero Chavela la contempló muy coqueta.

El alcohol le dio dolor y alivio,

Chavelita dejó la tomada y salió del olvido.

Ay, ay, ay, ahí viene la Chavela,

en Bellas Artes la esperan.

Una mujer con pantalón lo logró,

desafiando las reglas sociales de la nación.

Ya llegó la Chavelita,

y La Señora llegó para quedarse,

sus cantos al alma no se olvidan,

con brazos abiertos nos inspiran.

Alejandra Ramos Gomez, M.Ed., is an educational consultant and multidisciplinary artist from Juarez, Mexico. She is an alumna of the Harvard Graduate School of Education, where she works as a Teaching Fellow for the Human Development and Education Program. Ramos Gómez is the author of a bilingual poetry collection, Imperfecta, and loves writing in both languages.

Related Articles

Decolonizing Global Citizenship: Peripheral Perspectives

I write these words as someone who teaches, researches and resists in the global periphery.

Fibers of the Past: Museums and Textiles

Every place has a unique landscape.

Populist Homophobia and its Resistance: Winds in the Direction of Progress

LGBTQ+ people and activists in Latin America have reason to feel gloomy these days. We are living in the era of anti-pluralist populism, which often comes with streaks of homo- and trans-phobia.